There’s nothing like a good Tralfaz sighting. And there’s precious little else that’s good in

Don’t Axe Me, released in early 1958 by Warner Bros.

Here’s a scene in the kitchen of the Fudd residence. Mrs. Fudd (June Foray) has the same voice affectation as her husband. Gwacious! But you’ll note background artist Bill Butler has “Tralfaz” on a calendar.

This is from Bob McKimson’s unit, the post-shutdown version that made cartoons with weak stories and dull animation. Tedd Pierce put down his martini at Brittingham’s long enough to come up with an odd story. Elmer Fudd has a pet dog, who has the standard McKimson dog design. But he also has a pet duck. Let me “axe” something, Tedd. A pet duck?? That Elmer feeds in a dish like a dog or cat??

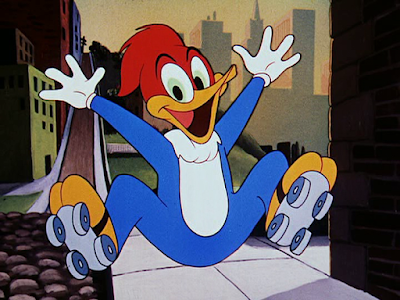

The pet duck in this happens to be Daffy, who has evidently been watching cartoons where the doppelganger dog gets victimised by Foghorn Leghorn. He repeats a routine from I can’t remember which cartoon where he puts a plate cover over the dog’s head, bangs on it, and the dog’s head shakes around. If this had been the earlier McKimson unit, where everyone flails around, the animation might have been a bit more fun. Here are some drawings.

What’s even weaker than this is Daffy leaps into the air and runs off. Not only do we not get a whole pile of crazy Daffy animation but Daffy yells “Quack, quack, quack, quack.” What? “Quack”? What happened to “Hoo Hoo!”? That’s what Daffy says. He even says it later in the cartoon! Tedd, what were you thinking?

Before the Tralfaz sighting we get another poorly paced routine. The dog decides to play charades with Mrs. Fudd (who proves two people with the same speech impediment are not twice as funny as one). The sequence just drags on. Then the dog gets frustrated and starts shouting at her. Why didn’t he just talk to her to begin with instead of playing charades for almost 50 seconds of screen time? Tex Avery pulls off the same gag in

Drag-a-long Droopy with the cow going “Moo, moo, moo! Baa, baa, baa!” But because Avery plays the scene shorter and faster, the cow speaking English is funny because it comes out of nowhere.

The second half is a little better than the first. Pierce borrows the old “shaving towel takes off the face” bit, and there’s a half-hearted version of the “He’s in there! He’s in there!” routine, undermined by the fact the dog has decided to go back to barking only. But the plot has Elmer pointing his rifle at Daffy, then the scene fades out. But it turns out he didn’t shoot Daffy. The next we see of the Duck, he’s still alive and in a roasting pan. After hearing the Fudds’ dinner guest is a vegetarian, the duck stalks out of the scene and the cartoon ends with a fade out.

Bob Gribbroek is the layout artist on this cartoon. Tom Ray, who had been working at various studios since the 1930s, gets his first Warner Bros. credit on this cartoon along with Ted Bonnicksen and George Grandpré, with Warren Batchelder likely assisting.

I feel bad about dumping on the McKimson unit’s cartoons. Bob McKimson seems to have gotten the short end at Warners. Friz Freleng orchestrated a switch in writers, and McKimson ended up with one who liked the sauce too much. McKimson’s unit was shut down several months before the studio closed for the last half of 1953 and when it reopened, there was no indication the unit would be brought back. When it was, even his own brother Chuck wouldn’t return to work for him. Too much time had passed, perhaps. One of his animators died on him. For a short time, his layout artist and background painter were having a hissing match. McKimson complained the front office kept assigning him castoffs, though certainly Ray and Batchelder were no lightweights (Ray ended up in the Jones unit). For several years, his layouts were by Bob Givens, who was no slouch.

It's arguable that the other directors at Warners had their best cartoons behind them by the late ‘50s, too. And by every account McKimson was a decent man, and a respected animator. But, for me, the laughs became fewer and farther between the longer he remained as a director. And the less said about things like

The Great Carrot Train Robbery (1969), the better.