He may have had trouble moving on foot but he sure got around. For a while in the 1950s—and this is before he became host of The Price is Right—Cullen was commuting from New York City to Los Angeles. He was emceeing shows in both cities.

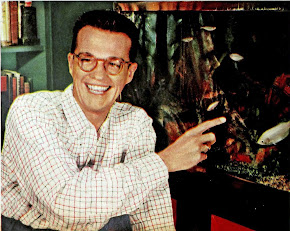

Cullen is still my favourite game show master of ceremonies. He was always friendly and amusing, and came across as enjoying his job, especially when it got a little silly. Here’s a fan magazine story, from the Radio-TV Mirror of January 1955. You’ll note the reference to Cullen’s first wife. I imagine the constant travel and work didn’t do wonders for their marriage. The fuzzy photos accompanied the article.

FUN WITH BILL CULLEN

Bill Cullen is a star with many, many points — most of them the rib-tickling kind

By GREGORY MERWIN

The neighbors gathered, and one said, "That Cullen boy, he'll never grow up to be President."

"Not even a senator?"

"No, he gets to the point too fast."

"Well, he's clever and good with his hands. He might be a surgeon."

"Young Bill? For every appendix he took out, he'd sew in a kitchen sink, a small convertible and a portable radio."

"How about a lawyer?"

"He's got too impish a sense of humor." .

"A garbage collector?"

"Too much responsibility."

"How about a radio star?"

"Hmm . . . why not. We can always turn him off." And so the neighbors, bless them — having decided Bill's fate — went back to their living rooms and tuned in Myrt and Marge while they waited for young Bill Cullen to grow up and become a star.

"They're still waiting," says Bill. "Every time someone calls me a star, I feel like asking for a show of hands."

The neighbors, however, had a couple of good points. Bill's smart enough to be a lawyer, studious enough to be a doctor, friendly enough to be a politician, but he couldn't have been any of those things. He just naturally fits in where he is, for Bill is innately cheerful and happy-go-lucky. He's fun whether you're with him in a studio or his own living room. He's good for the unexpected and a lot of laughs. But, although he "horses" around a good bit, he also works like one.

For eight months, he commuted six thousand miles each week. From CBS-TV's New York studios, where he participated in I've Got A Secret, he would hustle out to the airport and fly to CBS-TV's Hollywood studios, where he emceed Place The Face. He then about-faced and flew back to New York to do four hours on NBC's Roadshow. Of course, Bill was still doing his other shows: NBC's Walk A Mile, CBS Radio's Stop The Music, Mutual's It Happens Every Day, and CBS-TV's Name That Tune.

"Bill has a problem," says his agent Marty Goodman. "Bill is not only popular with the audience, but sponsors like him, too. It's a very pleasant kind of problem."

Toni, for example — which sponsored Place The Face — decided to hold onto their time, but replace The Face with Name That Tune. Bill, figuratively, just stayed at the microphone while one crew went out and another came in. One week, he was daring someone to remember a face — the next week, to remember a song. And it might as well be noted that, when Place The Face returned temporarily to a Saturday-night slot, Bill was called in again!

Ten or so shows a week can keep a man mighty busy, but Bill doesn't take a chance on having any spare time. He has hobbies. He has been — and, in some cases, still is — a musician, mechanic, aviator, artist, poet, photographer, fish fancier, playwright, comedian, magician, airline owner, and maybe a few other things. And he doesn't dabble. He jumps in head first where it's deep. He buys books and studies. He buys equipment and works.

"This accounts for Bill being right at home with everyone he interviews," says Mert Koplin, producer of Walk A Mile. "Bill is never stumped by a man's or woman's occupation. He talks almost anyone's language."

He never took up doctoring as a hobby (there's a law against it), but he has read enough medical books to know a knee cap as a patella. So nurses and medics like to talk to Bill . . . and so do engineers and housewives (Bill can cook up a fine meal), plus pilots and mechanics.

One day they thought they'd stump Bill with a contestant who worked on the Univac, the electronic brain, but Bill had read quite a bit about it.

"Matter of fact, I had been thinking of buying one," Bill said. The man noted that a Univac costs more than a million dollars. "I offered him ten per cent — and the rest of my life in easy payments."

The man explained that the Univac was large and required a room twenty by thirty feet. Frankly, there are already so many hobbies and gadgets in Bill's apartment that it's unlikely he could squeeze in another measuring only twenty by thirty inches. Last summer, Bill had to chop a hole in a bookcase to make space for a fish tank in the den. He had already sealed off access to the fireplace with another fish tank.

"I've grown to hate fish," he now admits, ruefully. "They're incredibly cannibalistic. They attack the young and weak and sick."

Bill boned up on fish, but he admits he had picked up the hobby inadvertently. He had originally bought them to use as subjects for color movies. Matter of fact, he had no intention of making movies, either, when he first walked into the camera store. He had seen a couple of flood-lights he liked in the window. The clerk asked Bill what kind of photography he did. Bill told him mostly "still." The man said the lights were for movies.

"So, in order to buy the lights, I first had to get a movie camera and a projector and a splicer and tripods and a mess of other things," Bill says. "The fish came afterwards."

But fish, of course, aren't gadgets. Gadget-wise, Bill owns magic paraphernalia, a flock of cameras, recording equipment and a lot of other hard stuff — including musical instruments and art materials — all jammed into shelves and closets. In one closet, there is a fine, sensitive altimeter which he once used in his private airplane.

"It's a good thing to have around the apartment," Bill says. "Every once in a while, I plug in the altimeter and check our altitude. It gives me confidence in the building."

Although Bill at the moment owns no plane, he hasn't by any means given up flying. He's an excellent pilot and, for a year or more, owned several planes and ran a small airline of his own. However, it got too expensive for even a high-rated radio star, and Bill sold all the planes. Now, when he gets a free day, he goes out to the airport and rents one.

"I just get up and roam," he says. "It's just a question of getting away from everything in that big quiet."

While Bill goes up mostly for relaxation and rest, he occasionally has gone sight-seeing or visiting friends in New England by plane. And there was that Friday he told his pretty brunette wife Carol to dress for dinner and then proceeded to drive her to the airport. Carol, conscious of their both having dressed nicely and properly for dinner out, turned two eyes curled with question marks at Bill, as he led her to the plane.

"We're flying to Boston for dinner, naturally," he said.

And they did. And, after dinner in Boston, they came back to Manhattan to see a movie. Naturally.

"It sounded like fun, going to Boston just for dinner," Bill recalls, "and it was."

This is the one thing Bill's friends find most consistent in him: He is fun. Bill's verve is as constant off the air as on. But he's no freak. Bill can be upset.

"He can be disturbed about something, but he swallows it up in front of you and smiles," says Millicent Holloway. "He just doesn't like to give others a hard time."

Millicent and her husband have been friends of the Cullens for years. She also assists Bill with a lot of his work and so knows him well. She recalls riding across town with him. Their cab stopped at a traffic light and Bill's eyes suddenly welled up with tears. He was staring at an old man on the sidewalk. The old man was tired and poor and wearing hand-me-downs which drooped to his feet. And there was so obviously nothing anyone could do for him any more.

"I got it, too," Millicent says, "and my eyes got real heavy and wet. Then Bill took it upon himself to pull us out of it and he swallowed it right down, and in the next block he had me distracted and chuckling about something."

His sensitivity to others is just one of many nice traits. He's also generous to an extreme. He has turned to Millicent in the office and said, "Please call the florist and have him send poinsettias to my mother. And, while you're at it, have them sent to Carol's mother and yours, too."

When a friend is hard up, Bill comes galloping up on a white steed. He's created jobs for friends who needed immediate help. He'll go to bat for someone in the business who needs a door opened. And then, too, Bill is brave.

Bravery is a word seldom required in talking about radio people. You meet few ravenous lions in studios, and not many dressing rooms are heavily mined, but everyone in the business says Bill is brave. He talks up and talks back, when he thinks he's right. And he talks up and back to producers, sponsors and other powerful men.

"Mostly it boils down to one thing that he is defending," a friend says, "and that is the right of the individual to act as an individual. You can make him angry by saying, 'Bill, you've got to do this my way.' He believes people need lots of elbow room for thinking and doing. And, incidentally, he'll fight just as hard for another person's right to the same privileges."

These somewhat serious dissections of Bill may come as a shock to many of his friends and fans — and to Bill, too. Bill, especially, for he refuses to be visibly impressed by Cullen.

Some of Bill's friends have, from time to time over the years, tried to take a good photograph of him. They'll find a fat cloud in the sky and tilt his chin up against that, and take special light readings, and figure this is going to be a picture worthy of Bill Cullen. But, just as the shutter clicks, Bill sticks out his tongue or crosses his eyes or wiggles his ears. Bill just can't take himself seriously in that sense. He will take your problems seriously, but not his and not himself.

Consider that apartment of his. You wouldn't dare walk in and ask him, "What's new?" You'd be liable to get an answer.

"The mynah is new."

Now a mynah — which everyone needs in his home like a hole in the roof — is a kind of starling that looks like a black crow. It is a rare bird and costs about $500 without cage, automatic drive and other accessories. What makes the mynah worth $500 is that it can be taught to repeat words better than a parrot. Now, this mynah that Bill took unto himself goes by the name of Henry — and calls everyone else "Charlie."

"Henry's simple to take care of," Bill says, with a wry smile. "You have to keep him out of drafts but, again, the room can't be too warm for him. And, if he isn't asleep on schedule, he's in a bad humor. His meals are more complicated than a French chef's. Henry's bananas have to be mashed. I must peel his orange, then break it into small segments, then peel the skin off the segments and then pick out all the seeds. And he doesn't eat domestic bird seeds. Only the expensive, imported kind."

Bill got Henry mostly for professional reasons. He hoped to teach Henry some phrases and then use him on radio and TV.

"As you know," Bill explains, "someone always has to say with enthusiasm, 'And here's Bill Cullen.' Well, I feel sorry for the guy who has to say that, especially with enthusiasm."

So Bill decided to train Henry the mynah to say, "And here's Bill Cullen." He made a recording of it and instructed his maid to keep the record going all day. Henry was kept in the same room with the phonograph, and the maid would bring in her ironing or whatever it was, and she played the record over and over. This went on for a week.

"With no results," Bill says. "I was ready to give up, but I figured I'd give the bird one more week."

The middle of the second week, Bill came in the front door, stopped suddenly and cocked his ear.

"I heard it over and over again, 'And here's Bill Cullen. And here's Bill Cullen. And here's Bill Cullen.'"

Bill grins as he explains, "It was the maid. She'd learned the line perfectly."

Now, in the interest of domestic science, Bill is trying to help the maid unlearn the line and give it to the mynah. And, when she does and he does, you'll meet Henry on the air.

"Bill's imaginative," says Mert Koplin, "and he's very much alive. From Bill, you expect the unexpected."

And Bill's friends generally expect to be surprised. He is seldom routine. For birthdays and holidays, he makes plans. But, any other time, he is likely to phone after six in the evening and say, "Let's get together tonight."

And, no matter where they go or what they do, an evening with Bill is guaranteed to be fun. At home, he likes to get the fireplace in business and roast weiners and toast marshmallows. He may call on his friends to act out in slow-motion a couple of scenes for a home movie. He tells a good story and he sings pretty well, with a warm, resonant voice.

"I've got five good notes," he says, "but I can't get above middle C."

If you want to talk seriously about politics or wars or people, you'll find Bill well-read and interested. If you want a sympathetic ear for your troubles, you couldn't ask for anyone more sensitive. But one thing's sure: When it's all over, and you leave Bill — you'll be smiling. For Bill Cullen's fun. He just will not leave you with a frown.

Mel Brooks once told a story about how he had appeared on a game show hosted by Cullen. After the taping was over, Cullen went over to shake Brooks' hand. But of course, being stricken with polio, he limped. Brooks didn't know of Cullen's condition and thought he was just walking funny, so he imitated Cullen's walk. Cullen laughed and said something to the effect of, "I'm so happy you did that! Most people who see me limping from polio feel sorry for me." Brooks was privately mortified.

ReplyDelete