Here’s a wonderful tale by Howard Beckerman for Back Stage published April 13, 1984. It starts out talking about the TV show The Duck Factory, a comedy in which nobody was interesting, let alone funny (the series died after 13 episodes and two Emmys for artwork). The column then morphs into a great little remembrance of Jim Tyer.

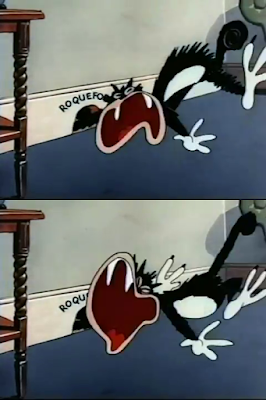

In recent years, some indignant cartoon fans have decided to defend the honour of Terrytoons from people who point out they’re not all that good. Jim Tyer has become their patron saint. When just about any other animator drew a take, they’d quickly build it and let it stay on the screen long enough for it to register as funny. Not Tyer. He was quirkier. His spikey-yet-rubbery takes were more in the form of silly movement, and in some scenes it seems he tossed in that kind of animation just for the hell of it. You’d never see it anywhere but a Terrytoon.

Tyer was employed for a time by Walt Disney so he certainly should have been able to come up with the fluid, intricate acting Uncle Walt wanted, but his way was more fun to him. Animation directors Gene Deitch and Ralph Bakshi have good things to say about Tyer. And so does Beckerman, a former Terrytooner, in his column. The only thing wrong with it is it isn’t long enough. I could read pages and pages more about Jim Tyer.

(Tyer, as a side note, was born in 1904. He must have lied about his age to get into the military or someone made a mistake. His obituary in the Bridgeport, Connecticut Post states he was a World War 1 Navy veteran, and further reports he was the naval escort on the U.S.S. Olympia for the Unknown Soldier's return from France and the first man to walk the honour guard at the Unknown Soldier's grave, all in 1921. Yet in 1920, he was a plumber at age 16, working for his brothers in Bridgeport. In 1924, he was employed by Southern New England Telephone. He vanishes from the Bridgeport Directory for three years then re-appears as a cartoonist in 1928).

Animators as Personalities

By Howard Beckerman

A short time ago, it was suggested that I meet with actor Jack Gilford to discuss a character that he was to portray in an up and coming television sitcom. I don’t know the name of the show or whether or not it will ever make it to the tube, but it was to be about life in a cartoon studio and the storyline included an old time animator, the character that Gilford was to undertake.

Jack Gilford is known for his performances in “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way to The Forum,” “Once Upon A Mattress,” “The Tenth Man,” “Catch-22” and numerous other Broadway, film and television productions. I spoke with this fine, veteran actor on the phone and we made a tentative agreement to meet. I thought that I might supply him with some background on the personality types that passed through the animation studios of New York and Hollywood.

Gilford left for the coast to film the shows before we could talk further. The producers, I am sure, must have made arrangements with some animators to include cartoon segments in the program. Perhaps they even arranged for Gilford to absorb some information about the nature of animation and its practitioners. I am truly sorry we did not have that casual meeting and I still think of some of the bits of past and present information that I could have shared with him.

Though the day to day thrashing out of a cartoon is not always a humorous enterprise, there have been many funny incidents and even funnier personalities who made up the crews at the various theatrical studios. Paradoxically, animation production is a group effort performed by solitary workers. Each animator slumped over a light board flipping drawings is lost in a world by himself. At each new twist of development of the sketched action the animator feels the thrill that comes from this solitary creative process. In time to the flipping pages you can almost hear them saying to themselves, “I’m a genius, I’m a genius!”

This work, which is so personal, can only be accomplished by persistent effort, and requires some kind of release. In the days of the theatrical studios where Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny or Popeye were the concerns of platoons of artists, it was often the practical joke that satisfied the pent up tensions.

The little tricks that were played on one another could take various forms, from the simple to the most complex. Smearing a bit of limburger cheese on the lightbulb under the desk of some unsuspecting artist could create peals of glee by the end of the day. Cutout paper shapes representing a cowboy’s spurs, deftly attached to someone’s heels as they went to the bank on payday, could bring laughter that even a small paycheck couldn’t obscure. In one studio the calm and quiet could be suddenly ruptured by a chorus of cowbells, bicycle bells and auto horns. The cacophony, emitting from noisemakers affixed to the animators’ tables, would continue for a short while and then end as mysteriously as it had begun. There was no calendar for this extemporaneous outpouring of acoustic confusion, and no one could ever predict when it might occur again.

One animator who wanted to be noticed by an attractive female employee hid himself in an oversize trash barrel. As she passed he popped up like a jack in the box, casting scraps of paper about and unsettling the startled woman. Occasionally the pranks would be turned on the general public, like the time a group dropped heated coins onto the sidewalk below, then watched as unsuspecting passersby stopped to retrieve the “hot” money.

It was not unusual for a prank to be devised around the very insecurities of the business. Lunch would often be the time for anxious discussion of the fate of a studio and its personnel. Once when the people returned from a local sandwich shop they were amazed to find that the chairs and desks had disappeared. They were ready to assume the inevitable and were prepared to pick up their final checks when they found that animator Jim Tyer had arrived back before them and had all the furniture removed from the area.

I suppose if there was one animator that I would have suggested as an image for a sitcom it would have been Jim Tyer. Though Tyer, who died in 1976, looked nothing like Gilford, he was the perfect happy eccentric to build a character on. Rosy-cheeked, bespectacled, balding and portly, Tyer was a polite and pleasant gentleman but at the same time the most fiercely puckish person you’d ever expect to encounter. He spent a lifetime in the studios, working in New York, Detroit, Miami and Hollywood, attempting to apply a style of animation that was highly personal, very funny and often against the demands of the studio director. This man, whom most of us remember as being always of middle age and looking like Skeezix’s Uncle Walt in the Gasoline Alley comic strip, could enter a reception room, bestow a bouquet of flowers on a bewildered young woman and request that she tell her boss that “the lion of the industry is here!”

Tyer could pull a prank in the most unlikely places. A street corner in a busy metropolis would be as much a stage for him as any of the dingy rooms of a 1930s animation studio. On[c]e in a lighthearted debate with a fellow artist he proceeded to tear the man’s trousers to shreds in front of surprised onlookers, and then graciously bought the bare legged victim a new pair at the nearest haberdasher. Jim Tyer could sit all day at a desk and produce a stack of delightfully whimsical drawings which when flipped would move with a distinct verve and a lack of concern for gravity and volume. While doing this he could maintain a steady flow of patter that would contain the most fantastic Alice-In-Wonderland references. There must be a hundred stories about Jim Tyer.

Will Friedwald, in an extensive, unpublished article containing interviews with many of Tyer’s associates, notes that this man who could include the most ribald bits of humor into a simple cartoon meant for family consumption (segments that either went by in a blur or were deleted before final camera), “could not bring himself to hate anyone . . because in a heart as big as Tyer’s he found no room for hate. He was a deeply religious man and every morning he would arrive from Bridgeport and stop at a local church before going to work.” He was basically a shy fellow but when the occasion called for extravagances in language he could cuss like a trooper, yet avoid offending the Deity. Even when he found time to do a risqué gag, it was always softened by his personal warm drawing style. Friedwald states that Tyer “spent his life trying to make people happy, trying to uplift their spirits and entertain them.”

If that program ever gets on the air, I for one hope that it includes a Jim Tyer-like character.

Great article. Thanks for posting here. Of course the unpublished (and definitely "unpolished" at the time) Will Friedwald article WAS published at long last in ANIMATION BLAST #6 (which I highly recommend everyone reading this to find).

ReplyDeleteBesides Jack Gilford,the only other high point to the long forgotten " Duck Factory " was Don Messick as Wally Wooster. The factory's voice man who had been doing it so long that sometimes he would get stuck in his cartoon voices.

ReplyDelete