Tributes flowed in the press when Jack Benny died on December 26, 1974. We’ve reprinted some. Here’s another, this time from the Geneva Daily Times of January 14, 1975. It’s more a eulogy to the past, really. I suspect many readers felt the same way as the writer. Interestingly enough, most of the people on the list appeared at one time on the Benny radio show, including one Spangler Arlington Brugh.

The great radio comedians

By JOE COOKE

(Mr. Cooke is a former Times reporter and desk man.)

When I learned of the passing of Jack Benny, my favorite comedian, I knew that sometime I would write a column about him and about some of the radio, television and movie people I have seen over the years.

Benny of course had no equal in his field. After his death the newspapers, magazines and TV-radio covered his life and accomplishments in detail. All I can add is that years ago his time slot on radio was a must for us. We waited with interest his "Jello again. This is Jack Benny." We wanted to hear from him and his sidekicks — Mary Livingston, Dennis Day, Rochester, Don Wilson, Phil Harris, the man who played department store floorwalker or sometimes a railroad car conductor, and all the others.

Jack's miserliness was on stage only. He was really very generous with his money, it has been said he gave over a million dollars to charity.

What can an ordinary fellow like me say about Benny? We, Laura and I, loved him because he could brighten up our day, our whole week, no matter how difficult things may have been.

Who can forget his running feud with Fred Allen? His famous imaginary railroad, the "Anaheim, Azusa and — Cucamonga?" His dungeon, with moats, wild animals, creaking doors, sirens and burglar alarms, for his money? Whatever became of the gas man who went downstairs to read the meter and never was seen again? Where is his Maxwell automobile now, whose wheezy engine noises were made by Mel Blanc? Do you remember Benny's violin lessons and the anguished French music teacher, also played by Blanc?

These remembrances come out of my own memory, from the radio and TV shows we had seen. I'll never forget them. But actually no one could really imitate the true Benny, with his bland expressions of surprise, pain or pleasure. He could say the one word "Well!" with an intonation that always brought down the house.

We of the older generation who were fortunate enough to know radio in the early days thank Benny for many happy hours. His was one of the few radio shows that was made over, intact, into a TV show, without change of cast, plot or meaning.

Jack Benny's death made me think back on some of the other theatrical highliners I had seen over the years, most of whom are now gone.

I mentioned Fred Allen. How well I remember his "Allen's Alley" and the queer characters who lived on this mythical street. I also remember his feud with Jack Benny, each one maligning the other on the air, but the best of friends otherwise. Fred's real name was John Florence Sullivan, a source says.

My father loved to listen to the late Eddie Cantor's radio show and so did I. Eddie was a song and dance man, of course, but also a comedian.

I grew up with Boris Karloff in his various roles as Frankenstein's monster, mad scientist and other weird characters. I saw him gentle down until when, before his death, he played mild loveable parts sometimes. But he always had that rather sinister lisp when he spoke which I never forgot.

A sinister triumvirate, all now deceased, included Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre and Sidney Greenstreet. The trio later added Lauren Bacall who became Bogart's wife in real life.

I like to remember the suave, immaculate appearance of the late Adolphe Menjou, a man of the world it there ever was one. But he didn't come from Paris, London or New York. He was born in Pittsburgh.

A great humorist I really can remember because he didn't die until 1935 was Will Rogers. He had the homespun dialogue down pat, but with a needle in it that could hurt. I saw him on the stage once when he was playing with Ziegfeld's Follies in New York. He talked sense with a twang while he twirled his lariat expertly.

The late Robert Taylor was my idea of a man about town, although he played other roles in the movies too. Somehow, to me at least, he seemed a little out of place as a working roustabout in dirty clothes. I saw him as a matinee idol, dressed in the height of fashion, with at least one lovely lady on his arm. I love Taylor's real name — Spanger Arlington Brugh.

Do you remember Ronald Colman, always fashionably dressed and with a delightful British accent? He came by the accent legally since he was born in Surrey, England. He was one of Jack Benny's friends, both on and off the screen. They had some fine skits together.

Other comedians, now gone, come to mind. Bert Lahr, with his funny laugh, Lew Lehr, another comic of great talent. And one of the tops in the field, Ed Wynn. Ed, if I remember correctly, was called the fire chief because his show was sponsored by an oil company. Ed did something I always wanted to do — he talked through the commercials and said what he thought of them, disbelieving some of the statements. I find myself doing that today as I watch current TV shows and listen to the high pressure commercial messages.

All this has traveled away from Jack Benny. He needs no kudos from me.

Sunday, 31 December 2017

Saturday, 30 December 2017

Joking With Jim Tyer

Here’s a wonderful tale by Howard Beckerman for Back Stage published April 13, 1984. It starts out talking about the TV show The Duck Factory, a comedy in which nobody was interesting, let alone funny (the series died after 13 episodes and two Emmys for artwork). The column then morphs into a great little remembrance of Jim Tyer.

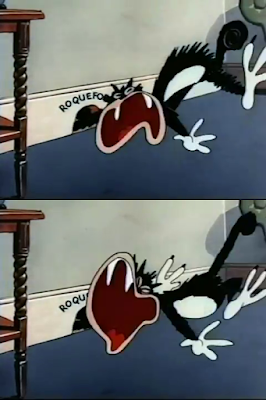

In recent years, some indignant cartoon fans have decided to defend the honour of Terrytoons from people who point out they’re not all that good. Jim Tyer has become their patron saint. When just about any other animator drew a take, they’d quickly build it and let it stay on the screen long enough for it to register as funny. Not Tyer. He was quirkier. His spikey-yet-rubbery takes were more in the form of silly movement, and in some scenes it seems he tossed in that kind of animation just for the hell of it. You’d never see it anywhere but a Terrytoon.

Tyer was employed for a time by Walt Disney so he certainly should have been able to come up with the fluid, intricate acting Uncle Walt wanted, but his way was more fun to him. Animation directors Gene Deitch and Ralph Bakshi have good things to say about Tyer. And so does Beckerman, a former Terrytooner, in his column. The only thing wrong with it is it isn’t long enough. I could read pages and pages more about Jim Tyer.

(Tyer, as a side note, was born in 1904. He must have lied about his age to get into the military or someone made a mistake. His obituary in the Bridgeport, Connecticut Post states he was a World War 1 Navy veteran, and further reports he was the naval escort on the U.S.S. Olympia for the Unknown Soldier's return from France and the first man to walk the honour guard at the Unknown Soldier's grave, all in 1921. Yet in 1920, he was a plumber at age 16, working for his brothers in Bridgeport. In 1924, he was employed by Southern New England Telephone. He vanishes from the Bridgeport Directory for three years then re-appears as a cartoonist in 1928).

Animators as Personalities

By Howard Beckerman

A short time ago, it was suggested that I meet with actor Jack Gilford to discuss a character that he was to portray in an up and coming television sitcom. I don’t know the name of the show or whether or not it will ever make it to the tube, but it was to be about life in a cartoon studio and the storyline included an old time animator, the character that Gilford was to undertake.

Jack Gilford is known for his performances in “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way to The Forum,” “Once Upon A Mattress,” “The Tenth Man,” “Catch-22” and numerous other Broadway, film and television productions. I spoke with this fine, veteran actor on the phone and we made a tentative agreement to meet. I thought that I might supply him with some background on the personality types that passed through the animation studios of New York and Hollywood.

Gilford left for the coast to film the shows before we could talk further. The producers, I am sure, must have made arrangements with some animators to include cartoon segments in the program. Perhaps they even arranged for Gilford to absorb some information about the nature of animation and its practitioners. I am truly sorry we did not have that casual meeting and I still think of some of the bits of past and present information that I could have shared with him.

Though the day to day thrashing out of a cartoon is not always a humorous enterprise, there have been many funny incidents and even funnier personalities who made up the crews at the various theatrical studios. Paradoxically, animation production is a group effort performed by solitary workers. Each animator slumped over a light board flipping drawings is lost in a world by himself. At each new twist of development of the sketched action the animator feels the thrill that comes from this solitary creative process. In time to the flipping pages you can almost hear them saying to themselves, “I’m a genius, I’m a genius!”

This work, which is so personal, can only be accomplished by persistent effort, and requires some kind of release. In the days of the theatrical studios where Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny or Popeye were the concerns of platoons of artists, it was often the practical joke that satisfied the pent up tensions.

The little tricks that were played on one another could take various forms, from the simple to the most complex. Smearing a bit of limburger cheese on the lightbulb under the desk of some unsuspecting artist could create peals of glee by the end of the day. Cutout paper shapes representing a cowboy’s spurs, deftly attached to someone’s heels as they went to the bank on payday, could bring laughter that even a small paycheck couldn’t obscure. In one studio the calm and quiet could be suddenly ruptured by a chorus of cowbells, bicycle bells and auto horns. The cacophony, emitting from noisemakers affixed to the animators’ tables, would continue for a short while and then end as mysteriously as it had begun. There was no calendar for this extemporaneous outpouring of acoustic confusion, and no one could ever predict when it might occur again.

One animator who wanted to be noticed by an attractive female employee hid himself in an oversize trash barrel. As she passed he popped up like a jack in the box, casting scraps of paper about and unsettling the startled woman. Occasionally the pranks would be turned on the general public, like the time a group dropped heated coins onto the sidewalk below, then watched as unsuspecting passersby stopped to retrieve the “hot” money.

It was not unusual for a prank to be devised around the very insecurities of the business. Lunch would often be the time for anxious discussion of the fate of a studio and its personnel. Once when the people returned from a local sandwich shop they were amazed to find that the chairs and desks had disappeared. They were ready to assume the inevitable and were prepared to pick up their final checks when they found that animator Jim Tyer had arrived back before them and had all the furniture removed from the area.

I suppose if there was one animator that I would have suggested as an image for a sitcom it would have been Jim Tyer. Though Tyer, who died in 1976, looked nothing like Gilford, he was the perfect happy eccentric to build a character on. Rosy-cheeked, bespectacled, balding and portly, Tyer was a polite and pleasant gentleman but at the same time the most fiercely puckish person you’d ever expect to encounter. He spent a lifetime in the studios, working in New York, Detroit, Miami and Hollywood, attempting to apply a style of animation that was highly personal, very funny and often against the demands of the studio director. This man, whom most of us remember as being always of middle age and looking like Skeezix’s Uncle Walt in the Gasoline Alley comic strip, could enter a reception room, bestow a bouquet of flowers on a bewildered young woman and request that she tell her boss that “the lion of the industry is here!”

Tyer could pull a prank in the most unlikely places. A street corner in a busy metropolis would be as much a stage for him as any of the dingy rooms of a 1930s animation studio. On[c]e in a lighthearted debate with a fellow artist he proceeded to tear the man’s trousers to shreds in front of surprised onlookers, and then graciously bought the bare legged victim a new pair at the nearest haberdasher. Jim Tyer could sit all day at a desk and produce a stack of delightfully whimsical drawings which when flipped would move with a distinct verve and a lack of concern for gravity and volume. While doing this he could maintain a steady flow of patter that would contain the most fantastic Alice-In-Wonderland references. There must be a hundred stories about Jim Tyer.

Will Friedwald, in an extensive, unpublished article containing interviews with many of Tyer’s associates, notes that this man who could include the most ribald bits of humor into a simple cartoon meant for family consumption (segments that either went by in a blur or were deleted before final camera), “could not bring himself to hate anyone . . because in a heart as big as Tyer’s he found no room for hate. He was a deeply religious man and every morning he would arrive from Bridgeport and stop at a local church before going to work.” He was basically a shy fellow but when the occasion called for extravagances in language he could cuss like a trooper, yet avoid offending the Deity. Even when he found time to do a risqué gag, it was always softened by his personal warm drawing style. Friedwald states that Tyer “spent his life trying to make people happy, trying to uplift their spirits and entertain them.”

If that program ever gets on the air, I for one hope that it includes a Jim Tyer-like character.

In recent years, some indignant cartoon fans have decided to defend the honour of Terrytoons from people who point out they’re not all that good. Jim Tyer has become their patron saint. When just about any other animator drew a take, they’d quickly build it and let it stay on the screen long enough for it to register as funny. Not Tyer. He was quirkier. His spikey-yet-rubbery takes were more in the form of silly movement, and in some scenes it seems he tossed in that kind of animation just for the hell of it. You’d never see it anywhere but a Terrytoon.

Tyer was employed for a time by Walt Disney so he certainly should have been able to come up with the fluid, intricate acting Uncle Walt wanted, but his way was more fun to him. Animation directors Gene Deitch and Ralph Bakshi have good things to say about Tyer. And so does Beckerman, a former Terrytooner, in his column. The only thing wrong with it is it isn’t long enough. I could read pages and pages more about Jim Tyer.

(Tyer, as a side note, was born in 1904. He must have lied about his age to get into the military or someone made a mistake. His obituary in the Bridgeport, Connecticut Post states he was a World War 1 Navy veteran, and further reports he was the naval escort on the U.S.S. Olympia for the Unknown Soldier's return from France and the first man to walk the honour guard at the Unknown Soldier's grave, all in 1921. Yet in 1920, he was a plumber at age 16, working for his brothers in Bridgeport. In 1924, he was employed by Southern New England Telephone. He vanishes from the Bridgeport Directory for three years then re-appears as a cartoonist in 1928).

Animators as Personalities

By Howard Beckerman

A short time ago, it was suggested that I meet with actor Jack Gilford to discuss a character that he was to portray in an up and coming television sitcom. I don’t know the name of the show or whether or not it will ever make it to the tube, but it was to be about life in a cartoon studio and the storyline included an old time animator, the character that Gilford was to undertake.

Jack Gilford is known for his performances in “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way to The Forum,” “Once Upon A Mattress,” “The Tenth Man,” “Catch-22” and numerous other Broadway, film and television productions. I spoke with this fine, veteran actor on the phone and we made a tentative agreement to meet. I thought that I might supply him with some background on the personality types that passed through the animation studios of New York and Hollywood.

Gilford left for the coast to film the shows before we could talk further. The producers, I am sure, must have made arrangements with some animators to include cartoon segments in the program. Perhaps they even arranged for Gilford to absorb some information about the nature of animation and its practitioners. I am truly sorry we did not have that casual meeting and I still think of some of the bits of past and present information that I could have shared with him.

Though the day to day thrashing out of a cartoon is not always a humorous enterprise, there have been many funny incidents and even funnier personalities who made up the crews at the various theatrical studios. Paradoxically, animation production is a group effort performed by solitary workers. Each animator slumped over a light board flipping drawings is lost in a world by himself. At each new twist of development of the sketched action the animator feels the thrill that comes from this solitary creative process. In time to the flipping pages you can almost hear them saying to themselves, “I’m a genius, I’m a genius!”

This work, which is so personal, can only be accomplished by persistent effort, and requires some kind of release. In the days of the theatrical studios where Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny or Popeye were the concerns of platoons of artists, it was often the practical joke that satisfied the pent up tensions.

The little tricks that were played on one another could take various forms, from the simple to the most complex. Smearing a bit of limburger cheese on the lightbulb under the desk of some unsuspecting artist could create peals of glee by the end of the day. Cutout paper shapes representing a cowboy’s spurs, deftly attached to someone’s heels as they went to the bank on payday, could bring laughter that even a small paycheck couldn’t obscure. In one studio the calm and quiet could be suddenly ruptured by a chorus of cowbells, bicycle bells and auto horns. The cacophony, emitting from noisemakers affixed to the animators’ tables, would continue for a short while and then end as mysteriously as it had begun. There was no calendar for this extemporaneous outpouring of acoustic confusion, and no one could ever predict when it might occur again.

One animator who wanted to be noticed by an attractive female employee hid himself in an oversize trash barrel. As she passed he popped up like a jack in the box, casting scraps of paper about and unsettling the startled woman. Occasionally the pranks would be turned on the general public, like the time a group dropped heated coins onto the sidewalk below, then watched as unsuspecting passersby stopped to retrieve the “hot” money.

It was not unusual for a prank to be devised around the very insecurities of the business. Lunch would often be the time for anxious discussion of the fate of a studio and its personnel. Once when the people returned from a local sandwich shop they were amazed to find that the chairs and desks had disappeared. They were ready to assume the inevitable and were prepared to pick up their final checks when they found that animator Jim Tyer had arrived back before them and had all the furniture removed from the area.

I suppose if there was one animator that I would have suggested as an image for a sitcom it would have been Jim Tyer. Though Tyer, who died in 1976, looked nothing like Gilford, he was the perfect happy eccentric to build a character on. Rosy-cheeked, bespectacled, balding and portly, Tyer was a polite and pleasant gentleman but at the same time the most fiercely puckish person you’d ever expect to encounter. He spent a lifetime in the studios, working in New York, Detroit, Miami and Hollywood, attempting to apply a style of animation that was highly personal, very funny and often against the demands of the studio director. This man, whom most of us remember as being always of middle age and looking like Skeezix’s Uncle Walt in the Gasoline Alley comic strip, could enter a reception room, bestow a bouquet of flowers on a bewildered young woman and request that she tell her boss that “the lion of the industry is here!”

Tyer could pull a prank in the most unlikely places. A street corner in a busy metropolis would be as much a stage for him as any of the dingy rooms of a 1930s animation studio. On[c]e in a lighthearted debate with a fellow artist he proceeded to tear the man’s trousers to shreds in front of surprised onlookers, and then graciously bought the bare legged victim a new pair at the nearest haberdasher. Jim Tyer could sit all day at a desk and produce a stack of delightfully whimsical drawings which when flipped would move with a distinct verve and a lack of concern for gravity and volume. While doing this he could maintain a steady flow of patter that would contain the most fantastic Alice-In-Wonderland references. There must be a hundred stories about Jim Tyer.

Will Friedwald, in an extensive, unpublished article containing interviews with many of Tyer’s associates, notes that this man who could include the most ribald bits of humor into a simple cartoon meant for family consumption (segments that either went by in a blur or were deleted before final camera), “could not bring himself to hate anyone . . because in a heart as big as Tyer’s he found no room for hate. He was a deeply religious man and every morning he would arrive from Bridgeport and stop at a local church before going to work.” He was basically a shy fellow but when the occasion called for extravagances in language he could cuss like a trooper, yet avoid offending the Deity. Even when he found time to do a risqué gag, it was always softened by his personal warm drawing style. Friedwald states that Tyer “spent his life trying to make people happy, trying to uplift their spirits and entertain them.”

If that program ever gets on the air, I for one hope that it includes a Jim Tyer-like character.

Labels:

Jim Tyer,

Terrytoons

Friday, 29 December 2017

I'm Here! I'm Here!

One of the funniest entrances in a Warner Bros. cartoon has to be when the Genie appears in the Bugs Bunny cartoon A-Lad-in His Lamp (released in 1948). Bugs Bunny rubs a lamp, it shakes, and poof! There’s the Genie. Since this is before Bob McKimson “calmed” his animators into a state of inertia, the Genie waves around his arms (even flapping his fingers together when he says the word “fly”). Bugs’ expression changes from wonder to annoyance.

Manny Gould, John Carey, Chuck McKimson and Phil De Lara receive the screen animation credits.

Writer Warren Foster borrowed Jim Backus’ routine as Hubert Updyke III from The Alan Young Show for the Genie and Backus voiced the part magnificently.

Manny Gould, John Carey, Chuck McKimson and Phil De Lara receive the screen animation credits.

Writer Warren Foster borrowed Jim Backus’ routine as Hubert Updyke III from The Alan Young Show for the Genie and Backus voiced the part magnificently.

Labels:

Bob McKimson,

Warner Bros.

Thursday, 28 December 2017

Rose Marie

Almost anyone can do an impression of Jimmy Durante. But the person who may have done the most fun impersonation is someone you probably wouldn’t think of.

It was Rose Marie.

She died today at age 94.

Long before The Dick Van Dyke Show, and long before answering “finding-a-man” questions on Hollywood Squares, Rose Marie graced the air a few times on the Jimmy Durante radio show with back-and-forth schtick, both of them sounding just like Durante. She even sang in Durante’s voice.

TV fans who watched her in the 1960s and ’70s may not realise just how far back her career went. She was already a seasoned trouper when she first appeared on the radio in 1927 as a child. And not on some kind of “aw, let’s bring on the cute kids” type show. Rose Marie was a star. By 1929, she was headlining for Lehn and Fink (makers of Lysol) on Thursday nights in a half-hour on the NBC Blue network. She was six years old.

We posted here about the ambitions of six-year-old Rose. Let’s move things up a few years when she was starting to appear in nightclubs, a “20-year-old hag,” as she put it. This is from the New York Sun of September 20, 1943.

Baby Rose Marie Grows Up

One-time Child Radio Singer Is Currently Featured at Versailles.

By ROBERT WILDER.

Fifteen years or so ago, when that magic thing known as distance was more important than the program which came through the earphones of early radio sets, Baby Rose Marie was plaintively singing the question: "What Can I Say Dear After I Say I'm Sorry?"

These nights at the Versailles, the quietly splendid night spot on East 50th street, Rose Marie, "an old hag of twenty" by her own admission, chants boisterously of "Pig Foot Pete From Kansas City" and in pleasantly husky tones sings a ballad or so from "Oklahoma!", surrounded the while by no little glamour and teauty as supplied by the stately lovelies known as the "Versighs." Rose Marie is one of the few entertainers who can be grateful for the years, for her early photographs, complete with bangs and ruffled pinafore, give the undeniable impression that Baby Rose Marie might have been slightly on the brattishly precocious side. At the age of 20, however, she is an extremely personable young woman with the poise that comes from years of appearing in public and a voice which, miraculously enough, she didn't ruin with her early efforts.

Back in 1936 Rose Marie made a determined effort to get rid of the Baby in her name by going to a hairdresser and having her straight hair done into ringlets and curls. Nothing much came of this, though. People still insisted upon referring to her as Baby Rose Marie. Even today her friends still address her as Baby, but the term is more one of affection than anything else.

Her Early Career.

Rose Marie comes as close to being the "trunk" baby of theatrical legend as any one else. Her father, Frank Curley, was a well-known Broadway performer for another generation, playing in "Forty-five Minutes From Broadway" and other successes of the period. By the time Rose Marie was 5 years old she had finished a six-month vaudeville tour, worked through an engagement of thirteen weeks at the Winter Garden and had made an early "talkie" for the movies. Her father, who may be suspected of prejudice, insists that she was walking at 9 months and talking at 13 months.

According to the story, Rose Marie got her first chance on the air by accident. In 1927 she was on the beach at Atlantic City entertaining a group of adults when an official of Station WPG happened by. He listened to the youngster and that night she sang the sad song of repentence, "What Can I say, Dear, &c," over the air.

In her own way Rose Marie made a little entertainment history despite the fact that she wasn't exactly the Shirley Temple of her day. She did very well, however, and was on her way to the top brackets when, as is usual, she began to grow up and the leggy stage when she no longer little and cute nor tall and beautiful. Booking agents began to look askance at the Baby in Baby Rose Marie. Rose Marie might have been shuffled off into oblivion, as so many child stars before her, but she was determined to be a singer and, knowing what she wanted, worked at the job of getting it.

Emerging from the jungle of adolescence, she started to work again. In 1938 she had a radio program, twice weekly, on Station WJZ, and since that time has been working steadily in clubs and hotels outside of New York.

That phrase, "just outside of New York," brings little comfort to theatrical folk. "Just outside New York" may just as well be Zanzibar and sometimes is. In any event, she kept busy, always with one eye on New York.

Never Wanted Opera.

"I never wanted to be an operatic star," Rose Marie says. She is no frustrated diva and she knows better than any one else what she can do and how well she can do it. "I like to do simple songs and comedy numbers. I'm really all right with comedy stuff."

Unmarried, but with a boy friend in Chicago, Rose Marie lives with her father, who has been traveling with her since she first began appearing in public. In her early days Papa Curley had frequent brushes with the law upon complaints from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and once had to pay a fifty-dollar fine for allowing the 5-year-old child to appear in a floor show at the Hotel New Yorker. In Special Sessions Baby Rose Marie offered to sing for Judges Healy, Direnzo and Vorhees to prove what an asset she was to Manhattan's night life, but the judges ruled otherwise but said she might broadcast.

The engagement at the Versailles, where she appears twice nightly, is the first big break of her adult career and Rose Marie is making the most of it Judging from her reception, the Versailles's patrons think this more than good enough.

I didn’t know Rose Marie, but I gained an additional respect for her as a person in reading Steve Wilson and Joe Florenski’s biography of Paul Lynde. Everyone thinks of him as a quick wit and a cut-up, but he was also an extremely nasty and self-destructive drunk. The book reveals that one person tried to help him and act a bit as his conscience while he was a mess was his Hollywood Squares stablemate Rose Marie. (Lynde finally did get his act together shortly before he died).

Rose Marie had mobility and a few other health issues in recent years. But her sense of humour, kindness and loyalty continued to shine through.

It was Rose Marie.

She died today at age 94.

Long before The Dick Van Dyke Show, and long before answering “finding-a-man” questions on Hollywood Squares, Rose Marie graced the air a few times on the Jimmy Durante radio show with back-and-forth schtick, both of them sounding just like Durante. She even sang in Durante’s voice.

TV fans who watched her in the 1960s and ’70s may not realise just how far back her career went. She was already a seasoned trouper when she first appeared on the radio in 1927 as a child. And not on some kind of “aw, let’s bring on the cute kids” type show. Rose Marie was a star. By 1929, she was headlining for Lehn and Fink (makers of Lysol) on Thursday nights in a half-hour on the NBC Blue network. She was six years old.

We posted here about the ambitions of six-year-old Rose. Let’s move things up a few years when she was starting to appear in nightclubs, a “20-year-old hag,” as she put it. This is from the New York Sun of September 20, 1943.

Baby Rose Marie Grows Up

One-time Child Radio Singer Is Currently Featured at Versailles.

By ROBERT WILDER.

Fifteen years or so ago, when that magic thing known as distance was more important than the program which came through the earphones of early radio sets, Baby Rose Marie was plaintively singing the question: "What Can I Say Dear After I Say I'm Sorry?"

These nights at the Versailles, the quietly splendid night spot on East 50th street, Rose Marie, "an old hag of twenty" by her own admission, chants boisterously of "Pig Foot Pete From Kansas City" and in pleasantly husky tones sings a ballad or so from "Oklahoma!", surrounded the while by no little glamour and teauty as supplied by the stately lovelies known as the "Versighs." Rose Marie is one of the few entertainers who can be grateful for the years, for her early photographs, complete with bangs and ruffled pinafore, give the undeniable impression that Baby Rose Marie might have been slightly on the brattishly precocious side. At the age of 20, however, she is an extremely personable young woman with the poise that comes from years of appearing in public and a voice which, miraculously enough, she didn't ruin with her early efforts.

Back in 1936 Rose Marie made a determined effort to get rid of the Baby in her name by going to a hairdresser and having her straight hair done into ringlets and curls. Nothing much came of this, though. People still insisted upon referring to her as Baby Rose Marie. Even today her friends still address her as Baby, but the term is more one of affection than anything else.

Her Early Career.

Rose Marie comes as close to being the "trunk" baby of theatrical legend as any one else. Her father, Frank Curley, was a well-known Broadway performer for another generation, playing in "Forty-five Minutes From Broadway" and other successes of the period. By the time Rose Marie was 5 years old she had finished a six-month vaudeville tour, worked through an engagement of thirteen weeks at the Winter Garden and had made an early "talkie" for the movies. Her father, who may be suspected of prejudice, insists that she was walking at 9 months and talking at 13 months.

According to the story, Rose Marie got her first chance on the air by accident. In 1927 she was on the beach at Atlantic City entertaining a group of adults when an official of Station WPG happened by. He listened to the youngster and that night she sang the sad song of repentence, "What Can I say, Dear, &c," over the air.

In her own way Rose Marie made a little entertainment history despite the fact that she wasn't exactly the Shirley Temple of her day. She did very well, however, and was on her way to the top brackets when, as is usual, she began to grow up and the leggy stage when she no longer little and cute nor tall and beautiful. Booking agents began to look askance at the Baby in Baby Rose Marie. Rose Marie might have been shuffled off into oblivion, as so many child stars before her, but she was determined to be a singer and, knowing what she wanted, worked at the job of getting it.

Emerging from the jungle of adolescence, she started to work again. In 1938 she had a radio program, twice weekly, on Station WJZ, and since that time has been working steadily in clubs and hotels outside of New York.

That phrase, "just outside of New York," brings little comfort to theatrical folk. "Just outside New York" may just as well be Zanzibar and sometimes is. In any event, she kept busy, always with one eye on New York.

Never Wanted Opera.

"I never wanted to be an operatic star," Rose Marie says. She is no frustrated diva and she knows better than any one else what she can do and how well she can do it. "I like to do simple songs and comedy numbers. I'm really all right with comedy stuff."

Unmarried, but with a boy friend in Chicago, Rose Marie lives with her father, who has been traveling with her since she first began appearing in public. In her early days Papa Curley had frequent brushes with the law upon complaints from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and once had to pay a fifty-dollar fine for allowing the 5-year-old child to appear in a floor show at the Hotel New Yorker. In Special Sessions Baby Rose Marie offered to sing for Judges Healy, Direnzo and Vorhees to prove what an asset she was to Manhattan's night life, but the judges ruled otherwise but said she might broadcast.

The engagement at the Versailles, where she appears twice nightly, is the first big break of her adult career and Rose Marie is making the most of it Judging from her reception, the Versailles's patrons think this more than good enough.

I didn’t know Rose Marie, but I gained an additional respect for her as a person in reading Steve Wilson and Joe Florenski’s biography of Paul Lynde. Everyone thinks of him as a quick wit and a cut-up, but he was also an extremely nasty and self-destructive drunk. The book reveals that one person tried to help him and act a bit as his conscience while he was a mess was his Hollywood Squares stablemate Rose Marie. (Lynde finally did get his act together shortly before he died).

Rose Marie had mobility and a few other health issues in recent years. But her sense of humour, kindness and loyalty continued to shine through.

Angel Pillow Fight

The next time your little one asks where snow comes from, just tell them its when angels have a pillow fight. Just like in the Van Beuren cartoon Happy Hoboes (1933)

This is Tom and Jerry at their not-finest. There isn’t much of a story, or gags for that matter, our heroes almost drown but show no emotion and somehow a train gets off its railway tracks (with a stream running down the middle solely to accommodate a gag) and into a logging camp consisting of one cook and one logger. Oh, well. It’s a Van Beuren cartoon.

George Stallings and George Rufle directed this blah entry.

This is Tom and Jerry at their not-finest. There isn’t much of a story, or gags for that matter, our heroes almost drown but show no emotion and somehow a train gets off its railway tracks (with a stream running down the middle solely to accommodate a gag) and into a logging camp consisting of one cook and one logger. Oh, well. It’s a Van Beuren cartoon.

George Stallings and George Rufle directed this blah entry.

Wednesday, 27 December 2017

Sid the Banana

How many comedians get eaten by a dinosaur?

I can think of only one—the great Sid Melton.

How can you not like Sid? He always came across as one of those “because-the-elephant-forgot-to-pack-his-trunk” New York vaudevillians. Enthusiastic. Corny. Ready to get grab a hat and cane and jump on stage at a moment’s notice, even giving you a bar or two of a Jolson impression on one knee.

Sid worked steadily for a long time. Not only was he in the aforementioned dinosaur film—Lost Continent with Whit Bissell, Hugh Beaumont and Acquanetta—not only did he star in Stop That Cab with the wonderful Iris Adrian (above right) and Leave It to the Marines (all in 1951), he had regular or recurring roles on a bunch of TV shows through five decades.

Not a lot of newspaper column ink was devoted to Sid, but we’ve found some columns we’ll pass along. First, to the Hartford Courant of August 27, 1961, where he talks a bit about the Danny Thomas Show, on which he began appearing several years into its run.

And then there were TV commercials, like the one below, which will end our post. There are two Sids in this. Cartoon fans should recognise the other Sid by his voice if nothing else. While Sid Melton was performing in summer 1938 in the stock cast at the St Regis Hotel in Fleischmanns, New York, the other New York-born Sid was touring with U.S. with a Major Bowes unit and had appeared in the Catskills. He was 97 when he died in 2006. Melton was 94 when he passed away in 2011.

I can think of only one—the great Sid Melton.

How can you not like Sid? He always came across as one of those “because-the-elephant-forgot-to-pack-his-trunk” New York vaudevillians. Enthusiastic. Corny. Ready to get grab a hat and cane and jump on stage at a moment’s notice, even giving you a bar or two of a Jolson impression on one knee.

Sid worked steadily for a long time. Not only was he in the aforementioned dinosaur film—Lost Continent with Whit Bissell, Hugh Beaumont and Acquanetta—not only did he star in Stop That Cab with the wonderful Iris Adrian (above right) and Leave It to the Marines (all in 1951), he had regular or recurring roles on a bunch of TV shows through five decades.

Not a lot of newspaper column ink was devoted to Sid, but we’ve found some columns we’ll pass along. First, to the Hartford Courant of August 27, 1961, where he talks a bit about the Danny Thomas Show, on which he began appearing several years into its run.

Sid Melton Gets Break On Danny Thomas ShowThe Chicago Tribune syndicate had Sid talk a bit more about his career in this interview published on March 31, 1963. The Thomas show would end the following season but was revived as Make Room For Granddaddy, giving Sid a chance to play Charley Halper again.

By LEONARD W. STONE

(Courant Staff Writer)

VAN NUYS, Calif. (Via Telephone) — Sid Melton isn’t married but he has a wife and they’re expecting a child.

If you’re not curious by now, there’s no hope. But just in case you want to find out what the whole thing’s about, all you have to do is turn you’re [sic] television dial to the “Danny Thomas Show” when it hits the fall trail on Oct. 2 (chs 3 and 12, 9 p.m.)

It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy either. Melton, who at age 40 is an electric bundle of nervous energy, is getting “the biggest break of his 21 years in show business. He is currently featured as Thomas’ nightclub owner friend, Charley Halper, in the popular situation comedy.

Harnassed Energy

For the 1961-62 season some of the Melton nervous energy will be harnessed. His wife will be the talented Pat Carroll who you’ll be able to see in person at the Storrowton Music Fair, West Springfield, for one week starting Monday in “On The Town.”

“She’s a talented comedienne with a keen sense of timing,” says Melton. Timing is a prerequisite for working with a former vaudeville actor. He has a rapid fire type of delivery. Pat and Sid are expecting a baby in the television series. Someone ought to tell her.

But most important to Melton is that he will appear in about 25 of the 32 installments of The Danny Thomas Show. He will also be given a greater part in the situation.

Honest Show

Melton calls the show one of the most honest attempts at entertainment on television. “We keep changing the script right up to the last minute,” he says. “There are no laugh tracks (pre-recorded laughter) on the ‘Danny Thomas Show.’” They tape before live audiences and rewrite as needed and do the whole thing over again. Where the audience reacts unfavorably the script is either edited or rewritten. This may be one of the reasons the show is going into its ninth year this fall.

Sheldon Leonard, who is producer and director, is also Thomas’ partner in Marterto Productions which produces many of the best comedy series on television. Numbered among its stable is “The Andy Griffith Show.”

Melton refers to those people as the “heavyweights of the industry. As for his part in the Thomas show: “I’m just happy that people laugh at me,” he says.

Sid Came Up Hard Way—But It’s Paying OffSid picked up a recurring part on Green Acres in 1965, playing one half of the brother combination of Alf and Ralph Monroe (Ralph was actually a woman). But it appears he wasn’t altogether happy, as he told the Newspaper Enterprise Association. This column appeared in newspapers on February 11, 1967.

By Walter Oleksy

“I WASN’T exactly born in a trunk in the Palace theater,” said Sid Melton, Danny Thomas’ sidekick on television, “altho my father, a vaudeville comedian, played there.”

“My dad, who performed under the name I. Meltzer, thought I should serve a long apprenticeship before going into show business so he waited until I was two years old before putting me into the act,” Sid told us in a recent interview.

“Seventeen years later, in 1940, I had $12.50 saved up and joined three other guys driving to Hollywood for what we hoped would be our big breaks.

“Hollywood wasn’t waiting for us with open arms, but I found some work and finally made an impression in the stage play, ‘The Man Who Came to Dinner.’

“Of my traveling companions, only Peter Leeds made the grade in show business. He’s a member of the Bob Hope troupe and does a lot of funny commercials. The other guys went back to their desk jobs. But that’s show business, to use an overworked phrase.”

Sid toured Europe during World War II, entertaining troops as part of the Hollywood Victory Caravan. After the war he appeared in movies such as “Knock on Any Door,” “The Steel Helmet,” and two Bob Hope pictures.

He also did television work, including regular roles on two series, Captain Midnight and It’s Always Jan, besides frequent guest shots on many series shows.

● ● ●

IN 1958, he joined the Danny Thomas Show, which had been on the air for six years. His performance, in a one-shot role, caught the public’s fancy and he was signed as a regular. He plays the part of Charley Halper, Danny’s night club owner friend.

“Now they’re building up my part even more,” Sid beamed. “I started out on the show as a bachelor, which I really am, and later took a TV wife, Pat Carroll. Now we’re parents of a baby boy.”

Sid impressed us as one of the hundreds of faces in the television crowd who has, thru hard work and natural talent, moved up front, center and is shouldering his big buildup like a pro.

What kind of a guy is Danny Thomas?

“Danny’s the greatest in the world,” Sid said. “He’s easy to work for, down to earth, and he gloats like a proud father if you can get the laughs. He’ll jump into the background and let any other performer take over—if he’s funny.

“Danny doesn’t believe in following the script too closely. We’ve got good writers but we always make changes as we go along. Danny and the executive producer-director, Sheldon Leonard, are always full of ideas.

“I used to come to rehearsals too well prepared. I had the script memorized cold. But Danny and Marjorie Lord, his TV show, are great add-libbers [sic]. They start with the script and take it from there. Gradually I got the hang of that kind of acting and believe me, it makes a show.

How does a confirmed bachelor manage to play an all-suffering husband and father convincingly?

“I’m an actor, ain’t I?” Sid responded.

But just to make sure all stays well, Sid admits he practices an old vaudeville superstition.

“I whistle in my dressing room.”

We Have No BananasSid never did a regular role, but he did surface on several episodes of The Golden Girls (playing a dead guy, not eaten by a dinosaur) and got called a number of times to work on several other series in the ‘90s. He was also cast in the film Lady Sings the Blues with Diana Ross. And there was also work on stage.

By ERSKINE JOHNSON

HOLLYWOOD (NEA) — People keep asking Sid Melton why he isn’t doing more television those days. It’s a good question and Sid keeps asking himself.

For seven years, as everyone knows, little Sid played Charlie Halper, owner of the club where Danny Thomas performed on The Danny Thomas Show. For seven years, with great comedy timing and a mobile face, Sid kept audiences laughing. With the end of the series no actor in Hollywood had a better track record as a second banana than Sid Melton.

“I'm still amazed,” he says, “but in three years I haven’t been asked to do a single TV pilot. I don’t understand it. I know I can make people laugh. I know I can make people happy.”

Now don’t get the idea that Sid inspired the war on poverty. He appears now and then as Alf Monroe, the inept carpenter on CBS-TV’s Green Acres. He has played other roles this season on The Phyllis Diller Show and on Run, Buddy, Run. He’s proud to he a small part of Green Acres because, “It’s a well-written fun show with no message, unlike most of the trash on television these days.”

He also welcome’s [sic] the change of pace from The Danny Thomas Show on which, he says, the director forever was saying to him, “Give me more of that Donald Duck grasping and sputtering.”

"As Charlie Halper,” he explains. “I had to give every line a trick delivery, it was all high key. Now, on Green Acres, it’s all much straighter and I can throw lines away.”

What Sid misses is another chance at a role like Halper.

“What I’d like to play is another strong banana in a comedy series. With this face it’s the only kind of role I really can play. But when I ask my agents about this, they just make a face, and my only answer to them is, ‘So I don’t look like Robert Culp.’ ”

With time on his hands Sid has been writing a book for a planned Broadway musical titled, “So Long Sam.” The story, he says, takes place in Japan with an all Oriental cast but all of the characters talk like those in “Guys and Dolls.”

He’s also working on his autobiography, for which Bob Hope has written the introduction. But there’s still time for him to keep asking himself that question about why he isn’t a regular on a comedy series.

He grins. “Maybe I’ll have my face changed so I WILL look like Robert Culp.”

And then there were TV commercials, like the one below, which will end our post. There are two Sids in this. Cartoon fans should recognise the other Sid by his voice if nothing else. While Sid Melton was performing in summer 1938 in the stock cast at the St Regis Hotel in Fleischmanns, New York, the other New York-born Sid was touring with U.S. with a Major Bowes unit and had appeared in the Catskills. He was 97 when he died in 2006. Melton was 94 when he passed away in 2011.

Labels:

Erskine Johnson

Tuesday, 26 December 2017

Toys in a Cycle

Before we leave our holiday posts behind for another year, let’s re-create some cycle animation from The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives, released early in the New Year of 1933. 16 drawings (one foot of film) make up a cycle of toys that are cheering because, well, there are crowds cheering in a bunch of Harman-Ising cartoons released by Warner Bros.

I won’t post the individual drawings this time. Instead, I’ll slow down the cycle a little bit.

Veterans Ham Hamilton and Norm Blackburn are credited on-screen with the animation. The song “The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives” was written by Harry Woods and copyright in October 1931. The same guy who did the falsetto males in a lot of the H-I Merrie Melodies (Max Maxwell?) plays the poor kid in this one.

What? This is reused animation from Red Headed Baby (1931, drawn by Hamilton and Maxwell)? Yes, you’re correct.

I won’t post the individual drawings this time. Instead, I’ll slow down the cycle a little bit.

Veterans Ham Hamilton and Norm Blackburn are credited on-screen with the animation. The song “The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives” was written by Harry Woods and copyright in October 1931. The same guy who did the falsetto males in a lot of the H-I Merrie Melodies (Max Maxwell?) plays the poor kid in this one.

What? This is reused animation from Red Headed Baby (1931, drawn by Hamilton and Maxwell)? Yes, you’re correct.

Labels:

Harman-Ising,

Warner Bros.

Monday, 25 December 2017

Santa Sells

“Why, it’s good ol’ Santy!” exclaims narrator Gil Warren, as flying reindeer canter into the moonlight in Tex Avery’s Holiday Highlights (1940).

Cut to a closer shot. Santa Claus isn’t delivering presents. Maybe he’s earning money to make them by selling ice cream. Yes, in winter.

Chuck McKimson is the credited animator.

Cut to a closer shot. Santa Claus isn’t delivering presents. Maybe he’s earning money to make them by selling ice cream. Yes, in winter.

Chuck McKimson is the credited animator.

Labels:

Tex Avery,

Warner Bros.

Sunday, 24 December 2017

Christmas Comfort For the Troops

No doubt Jack Benny’s writers threw away ideas for scripts that just didn’t work. We’ve had to do the same thing with our Benny Christmas post.

At first, we wanted to write something about Christmas With Jack Benny, an industrial film Jack made for Roy Grandey Productions in the early ‘60s for the Salvation Army Winter Fund. But I can’t find out anything about it, so that idea was out.

Next, we came across a story in the New York Herald Tribune that Jack was about to be on the very first bill of the Keith Albee Theatre in Flatbush, Queens, on Christmas Day 1928. After digging and a lot of confusion, I found ads for the bill and a story on its opening in the Brooklyn Daily Star of the following day. Jack was mentioned nowhere. It appears he wasn’t on the bill after all. I did find stories and box ads about Jack playing Proctor’s 58th Street (newly rebuilt) the week before and the Hippodrome on 6th Avenue the week after (Billboard’s reviewer sniffed that critics had probably memorised Benny’s act as they had seen it so many times). So that idea was out, too.

Instead, we’ll bring you a couple of related wire service Christmas stories from 1950 that only indirectly involve Jack Benny. Even today, many people enjoy listening to Jack’s old radio shows. But imagine that you’re several thousand miles away from home in a war zone. Wouldn’t you like some kind of reminder of home? This story is from December 24th. There is no byline.

Jack Benny gave much of his time to help others, even on Christmas. Even if he couldn’t be there in person.

At first, we wanted to write something about Christmas With Jack Benny, an industrial film Jack made for Roy Grandey Productions in the early ‘60s for the Salvation Army Winter Fund. But I can’t find out anything about it, so that idea was out.

Next, we came across a story in the New York Herald Tribune that Jack was about to be on the very first bill of the Keith Albee Theatre in Flatbush, Queens, on Christmas Day 1928. After digging and a lot of confusion, I found ads for the bill and a story on its opening in the Brooklyn Daily Star of the following day. Jack was mentioned nowhere. It appears he wasn’t on the bill after all. I did find stories and box ads about Jack playing Proctor’s 58th Street (newly rebuilt) the week before and the Hippodrome on 6th Avenue the week after (Billboard’s reviewer sniffed that critics had probably memorised Benny’s act as they had seen it so many times). So that idea was out, too.

Instead, we’ll bring you a couple of related wire service Christmas stories from 1950 that only indirectly involve Jack Benny. Even today, many people enjoy listening to Jack’s old radio shows. But imagine that you’re several thousand miles away from home in a war zone. Wouldn’t you like some kind of reminder of home? This story is from December 24th. There is no byline.

Radio Stars Join to Give Troopers Special Package as Christmas GiftThe following story appeared in newspapers the next day. The war correspondent who filed this report was later killed in a riot; beaten to death while on his way to cover a bus strike in Singapore on May 12, 1955. Communists were blamed.

HOLLYWOOD—(U.P.)—It will be a merrier Christmas for American fighting men throughout the world when Armed Forces Radio Service sends out its special short-waved Christmas package. Christmas carols and the familiar voices of Bing Crosby and Jane Russell will form a backdrop of home for GIs behind the booming guns in Korea and the lonely outposts of Europe.

AFRS has recorded more than 44 hours of the best radio programs of the year, along with special yuletide features, to beam their way tomorrow and Monday. Jack Benny, Red Skelton, Bob Hope and uncounted glamor girls will sing and cut up for the service men.

GIs also will hear the Los Angeles Rams-Cleveland Brown championship professional football game Christmas Day, the day after it is played. “A real present for the boys,” said an AFRS spokesman. “Football is our most popular program.”

Fighting men have their choice of religious services, sports, music and command performances by the favorite stars of screen and radio—even grand opera. Soldiers and sailors from Miami, Cleveland, Philadelphia and New York will hear friends and celebrities from their own home towns.

Hospitalized veterans will be the only persons in this country to hear the program, the most extensive ever arranged for radio.

The role of Santa Claus is filled by AFRS, a combined operation of all branches of the military. Col. William M. Wright, Jr., commands the Hollywood center, which services 68 far-flung stations from Pusan, Korea, to North Africa.

Included in the show business Christmas special will be such stars as Ann Blythe, Jeanne Crain, Pat O'Brien and MacDonald Carey.

Home front and world-wide news will keep GIs on all fronts abreast of the yuletide festivities at home.

AFRS, deluged by mail from men overseas clamoring for their favorite programs, gets the cooperation of radio networks and motion picture studios in producing its year-round shows.

Without that cooperation AFRS would be forced out of business. The cost of talent alone would be astronomical.

Private stations and networks also give AFRS the right to transcribe and re-broadcast many of their commercial programs, entirely free of charge.

The military radio went into operation shortly after Pearl Harbor and is headquartered in a two-story building in Hollywood.

As soon as its Christmas show is out of the way, it will go to work on a New Year's Day “present” for its listeners—broadcasts of the Rose, Sugar, Cotton and Orange bowl football games.

It's Quiet Christmas Eve Up in FoxholesSoldiers in Korea got to see Jack Benny in person. He had wanted to go in 1950 after Al Jolson performed for soldiers there but was advised by his doctor not to (Variety, Dec. 6, 1950). He finally went in July the following year (with Frank Remley and Errol Flynn) but the tour was cut short as Jack physically couldn’t deal with the grind in the oppressive war zone. That didn’t stop him from entertaining for the men and women who served their country. Louella Parsons reported in her column that Benny and Ann Blyth spent Christmas Day 1951 in Beaumont, Texas putting on a show for wounded vets, and then taking the show to army bases in New Mexico.

By GENE SYMONDS

SOMEWHERE NORTH OF SEOUL, Dec. 24.—(UP)—It's a quiet Christmas Eve up here in the foxholes—quiet and frightening and bitter cold.

There are no Christmas trees, no presents, no laughing friends shouting, "Merry Christmas," no tousled-haired kids to creep down stairs before dawn to see what Santa Claus brought them. Christmas Eve here is a machine gun sitting on the edge of your foxhole with the bolt back ready to go. It's a pale, full moon casting grotesque shadow among the fierce, rugged mountain peaks around you. It's your buddy crouching in the bottom of a freezing dugout with a blanket around his shoulders to smoke a cigarette.

COLD, CALM NIGHT

It might have been a night like this in Bethlehem 1,950 years ago when Christ was born—the night clear, cold, calm.

Out there, across those mountain peaks a few miles away, are the Communists. They have been building up a long time and tonight would be a nice time for them to strike.

Back from the front a short way in command tents and dugouts there are small fires, some companionship and perhaps a bottle or two that someone managed to hold on to. The talk, what there is of it, is all of home: “I wonder what the folks will be doing tonight?” and “I wonder what Mary got the kids for Christmas?” and “I hope to hell I am home for Christmas next year.”

SOME RADIOS

Some of the tents have radios and we can listen to Christmas programs from the Armed Forces Radio station in Seoul. It helps a little hearing familiar voices like Jack Benny and Charlie McCarthy; yes, it helps a little, but not much.

There's a thin layer of snow on everything and you can feel the ground tighten up as it freezes solid after a brief period of relatively warm weather. In Seoul there will be a midnight mass for United Nations troops but there will be no midnight services for Koreans, because of the curfew. Those Koreans who have managed to hang on to their radios will listen along with the soldiers to services broadcast from Tokyo.

Driving back from the front the cold bites deeper into your flesh and you feel sorry for the lonely MP's guarding bridges and roads. Some of them are permitted to have fires if they are far enough back from the front. They spend Christmas Eve trying to keep warm.

There are not many refugees on the roads tonight. They have stopped wherever they could for the night in homes still standing after two successive waves of fighting, in barns and in stables.

It is not unlikely that a Korean babe will be born along the road in some shabby building this Christmas Eve, 1950, in Korea.

Jack Benny gave much of his time to help others, even on Christmas. Even if he couldn’t be there in person.

Labels:

Jack Benny

Saturday, 23 December 2017

He Didn't Want to Make Cartoons

What started out as publicity interview for a Christmas show turned into an attempt by Walt Disney to justify why he wasn’t making many cartoons any more.

It boiled down to a word spelled M-O-N-E-Y.

Well, kind of.

After going on about the prohibitive cost of animation, Disney admitted to the Philadelphia Inquirer in a 1958 interview that the live-action westerns he put on TV were, to be honest, money-losers. But the prohibitive cost didn’t stop Disney from making those. And then he revealed that, gosh, golly, he never really wanted to make cartoons in the first place.

In the ‘40s, it seemed Disney was more interested in technology than animation. There was Fantasound. Then there was matte work to marry live action to animation (something Max Fleischer had been doing in the 1920s). A decade later he jumped on 3D, albeit briefly. Then in the ‘60s, xerography for One Hundred and One Dalmations. By that time, he had a huge theme park that took up a lot of his interest, immersing himself in a sentimental and wonder-filled America as he wanted it to be. Oh, and he had dived into the family feature film business with nary a drawing to be seen. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Oscars for Short Subject cartoons started going to other studios during World War Two.

Fortunately for us all, despite his dream of being the next King Vidor or Cecil B. DeMille, Walt Disney did go into the animation business. One can wonder how many distributors might have taken a pass on releasing cartoon short subjects had they not jumped on board in the wake of the popularity of the early Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies (remember that neither Warners nor MGM distributed cartoons at the time Mickey came along).

The Christmas show mentioned in the story below consisted of Jack Hannah’s crew of Al Coe, Volus Jones, Les Clark and Bob McCrea supplying animation of various Disney characters to stitch together some of the studio’s old Christmas cartoons and scenes from features. The studio was adept at this kind of thing, especially when Professor Ludwig Von Drake was used as a linking device; he remains my favourite Disney character.

This story appeared on December 14, 1958.

For Walt Disney Christmas Is Bigger Than All of Us

BY HARRY HARRIS

TINKER BELL, who lost her weekly “hostessing” job when ABC's Wednesday “Disneyland” became the Friday (8 P. M., Channel 6) “Walt Disney Presents,” helps get things rolling again this week on Disney's special Christmas show, “From All of Us to All of You.”

The program’s emphasis has been on flesh-and-blood characters like Elfego Baca and John Slaughter lately, but on Friday night Disney's pen-and-ink people will get an almost uninterrupted inning.

Tinker, Mickey Mouse and Jiminy Cricket have major roles in a holiday hour featuring “living Christmas cards” enlisting the talents of Peter Pan, Bambi, Pinocchio, Cinderella, Snow White and other small-fry favorites.

The only human on the premises will be Disney himself, and for the occasion this big, big man in Hollywood creative circles has consented to undergo shrinking to Tom Thumb size, “because Christmas is bigger than all of us.”

As far as TV’s concerned, the Disney drawing boards haven't been getting much of a workout lately only six cartoon shows were scheduled for the entire season. In Hollywood recently we asked Mr. D. how come.

“Cartoons are darned expensive,” he said. “In the Christmas show alone, for instance, we’ve got about a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of new stuff.

“A lot of people don't discriminate between good cartoons and cheap ones, but we keep betting there’s a percentage who prefer quality. Otherwise, we’d be stupidly throwing money away.

“We’re preparing ‘Sleeping Beauty’ for theaters. It will run only an hour and 15 minutes, but it will cost $6,000,000. That’s another reason we’re going easier on TV cartoons. Everybody who draws half-way decent is working on ‘Sleeping Beauty.’

“The Duck and the Mouse aren't on the retired list. We’ve got plenty of projects for them and for Pluto for this year and later. (Disney’s original seven-year pact with ABC still has two full seasons to go.)

“It’s true we're using cartoons more sparingly in the afternoons (“Mickey Mouse Club,” cut to a half-hour last year, is now aired only three times a week, at 5:30 P. M., with the real people-peopled “Adventure Time” slotted on Tuesdays and Thursday), but how many cartoons are there in the whole business? “You can’t keep filling a program with cartoons day after day for 26 weeks.

“We had to withdraw ‘Tomorrowland’ from our schedule this season because of the pressure of getting them out in time to keep up with scientific advances. And the cartoon segments were very expensive. ‘The Friendly Atom,’ which is being used in schools and by the Air Force, cost close to $400,000.

“Some of our TV cartoons are 40 percent new. We don't ‘get rid of old stuff.’ The old cartoons are valuable. We can still sell them to theaters. In fact, we still have quite a few we haven’t used on television yet. They won’t let me have the feature films. They say, ‘Why put Snow White’ on TV, when every time we send it out to theaters it’s worth $2,000,000?’

“Our interest in cartoons hasn’t dwindled. We’re doing as much animation as ever, but we’ve diversified.

“We’re doing a lot of nature films and stories with live actors. We got into live pictures when dollars were frozen in England and the only way we could get our money out was to make pictures there.

“Actually,” Walt confided, “if circumstances hadn’t forced me into it, I’d never have gone into the cartoon business. I was interested in live films. I wanted to be a director. Only the fact that I couldn’t get a job made me go back to the drawing board.”

Disney denies that his stress on Westerns this year—six Bacas and six Slaughters are definitely set, and there may be more—was dictated by a losing rating battle with “Wagon Train” last season.

“We’ve had Westerns from the first,” he pointed out, “as part of ‘Frontierland.’

“I love Westerns and adventure stories when they’re true stories, not necessarily documentaries, but more or less based on fact American history has always intrigued me. Our country is so young. People don’t realize how young.

“My own Dad was a fiddler who played with a little trio that passed the hat in front of frontier saloons. My mother and my uncles knew people who have become legends of the old West.

“John Slaughter cleaned up the mess left in Cochise county by Wyatt Earp, and in the personal effects of his widow were shares of Disney stock.

“I think our Westerns are very good ones. And they’re expensive. The Baca and Slaughter hours cost us about $300,000 apiece, and we only get back $100,000 on the first showing and $60,000 for each repeat. And we pay residuals on the repeats.

“Profit or loss, it all goes into the pot. We’ll spend $1,800,000 this year on TV material over what we’ll get not counting ‘Zorro.’

“If you want to make a Western cheaply, you just don’t put in any action. You shoot it in front of a wagon and have your actors sit around a fire and talk. Or you shoot through a wagon wheel and have a few Indians go by.

“But if you go out on location and shoot real action, as we do, that alone costs $20,000 a day.”

He may assemble Baca and Slaughter segments for release as theater fare abroad. Zorro is definitely slated for such treatment. But in general Disney is opposed to transferring his strictly-TV characters to U. S. theater screens. Dave Crockett? “The theaters begged for Crockett,” he said.

He sees advantages and disadvantages to the switch from Wednesday at 7:30 to Fridays at 8.

“There were a lot of letters opposing Wednesdays because it interfered with Boy Scouts, Christian Endeavor meetings and various church functions.

“On the other hand, I opposed the later hour, because there's the problem of kids staying up, and the kids control the dials. But it was pointed out that, with no school next day, they can stay up later Fridays. My brother, Roy, was concerned, too, because he felt Friday was a theater night, and it wasn’t fair to theater owners.

“We didn’t try to get away from competition. There’s always competition. And sometimes it’s too bad.

“One of my favorites is Groucho Marx. I didn’t want ‘Zorro’ scheduled against him, but I had no say in the matter.

“I saw Groucho once, and he told me his daughter came to him and asked, ‘Daddy, do I have to look at you?’ Groucho replied, ‘This is a free country.’ ‘So she turned on “Zorro,”’ Groucho said, ‘and I watched it from the background myself!’”

It boiled down to a word spelled M-O-N-E-Y.

Well, kind of.

After going on about the prohibitive cost of animation, Disney admitted to the Philadelphia Inquirer in a 1958 interview that the live-action westerns he put on TV were, to be honest, money-losers. But the prohibitive cost didn’t stop Disney from making those. And then he revealed that, gosh, golly, he never really wanted to make cartoons in the first place.

In the ‘40s, it seemed Disney was more interested in technology than animation. There was Fantasound. Then there was matte work to marry live action to animation (something Max Fleischer had been doing in the 1920s). A decade later he jumped on 3D, albeit briefly. Then in the ‘60s, xerography for One Hundred and One Dalmations. By that time, he had a huge theme park that took up a lot of his interest, immersing himself in a sentimental and wonder-filled America as he wanted it to be. Oh, and he had dived into the family feature film business with nary a drawing to be seen. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Oscars for Short Subject cartoons started going to other studios during World War Two.

Fortunately for us all, despite his dream of being the next King Vidor or Cecil B. DeMille, Walt Disney did go into the animation business. One can wonder how many distributors might have taken a pass on releasing cartoon short subjects had they not jumped on board in the wake of the popularity of the early Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies (remember that neither Warners nor MGM distributed cartoons at the time Mickey came along).

The Christmas show mentioned in the story below consisted of Jack Hannah’s crew of Al Coe, Volus Jones, Les Clark and Bob McCrea supplying animation of various Disney characters to stitch together some of the studio’s old Christmas cartoons and scenes from features. The studio was adept at this kind of thing, especially when Professor Ludwig Von Drake was used as a linking device; he remains my favourite Disney character.

This story appeared on December 14, 1958.

For Walt Disney Christmas Is Bigger Than All of Us

BY HARRY HARRIS

TINKER BELL, who lost her weekly “hostessing” job when ABC's Wednesday “Disneyland” became the Friday (8 P. M., Channel 6) “Walt Disney Presents,” helps get things rolling again this week on Disney's special Christmas show, “From All of Us to All of You.”

The program’s emphasis has been on flesh-and-blood characters like Elfego Baca and John Slaughter lately, but on Friday night Disney's pen-and-ink people will get an almost uninterrupted inning.

Tinker, Mickey Mouse and Jiminy Cricket have major roles in a holiday hour featuring “living Christmas cards” enlisting the talents of Peter Pan, Bambi, Pinocchio, Cinderella, Snow White and other small-fry favorites.

The only human on the premises will be Disney himself, and for the occasion this big, big man in Hollywood creative circles has consented to undergo shrinking to Tom Thumb size, “because Christmas is bigger than all of us.”

As far as TV’s concerned, the Disney drawing boards haven't been getting much of a workout lately only six cartoon shows were scheduled for the entire season. In Hollywood recently we asked Mr. D. how come.

“Cartoons are darned expensive,” he said. “In the Christmas show alone, for instance, we’ve got about a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of new stuff.

“A lot of people don't discriminate between good cartoons and cheap ones, but we keep betting there’s a percentage who prefer quality. Otherwise, we’d be stupidly throwing money away.

“We’re preparing ‘Sleeping Beauty’ for theaters. It will run only an hour and 15 minutes, but it will cost $6,000,000. That’s another reason we’re going easier on TV cartoons. Everybody who draws half-way decent is working on ‘Sleeping Beauty.’

“The Duck and the Mouse aren't on the retired list. We’ve got plenty of projects for them and for Pluto for this year and later. (Disney’s original seven-year pact with ABC still has two full seasons to go.)

“It’s true we're using cartoons more sparingly in the afternoons (“Mickey Mouse Club,” cut to a half-hour last year, is now aired only three times a week, at 5:30 P. M., with the real people-peopled “Adventure Time” slotted on Tuesdays and Thursday), but how many cartoons are there in the whole business? “You can’t keep filling a program with cartoons day after day for 26 weeks.

“We had to withdraw ‘Tomorrowland’ from our schedule this season because of the pressure of getting them out in time to keep up with scientific advances. And the cartoon segments were very expensive. ‘The Friendly Atom,’ which is being used in schools and by the Air Force, cost close to $400,000.

“Some of our TV cartoons are 40 percent new. We don't ‘get rid of old stuff.’ The old cartoons are valuable. We can still sell them to theaters. In fact, we still have quite a few we haven’t used on television yet. They won’t let me have the feature films. They say, ‘Why put Snow White’ on TV, when every time we send it out to theaters it’s worth $2,000,000?’

“Our interest in cartoons hasn’t dwindled. We’re doing as much animation as ever, but we’ve diversified.

“We’re doing a lot of nature films and stories with live actors. We got into live pictures when dollars were frozen in England and the only way we could get our money out was to make pictures there.

“Actually,” Walt confided, “if circumstances hadn’t forced me into it, I’d never have gone into the cartoon business. I was interested in live films. I wanted to be a director. Only the fact that I couldn’t get a job made me go back to the drawing board.”

Disney denies that his stress on Westerns this year—six Bacas and six Slaughters are definitely set, and there may be more—was dictated by a losing rating battle with “Wagon Train” last season.

“We’ve had Westerns from the first,” he pointed out, “as part of ‘Frontierland.’

“I love Westerns and adventure stories when they’re true stories, not necessarily documentaries, but more or less based on fact American history has always intrigued me. Our country is so young. People don’t realize how young.

“My own Dad was a fiddler who played with a little trio that passed the hat in front of frontier saloons. My mother and my uncles knew people who have become legends of the old West.

“John Slaughter cleaned up the mess left in Cochise county by Wyatt Earp, and in the personal effects of his widow were shares of Disney stock.

“I think our Westerns are very good ones. And they’re expensive. The Baca and Slaughter hours cost us about $300,000 apiece, and we only get back $100,000 on the first showing and $60,000 for each repeat. And we pay residuals on the repeats.

“Profit or loss, it all goes into the pot. We’ll spend $1,800,000 this year on TV material over what we’ll get not counting ‘Zorro.’

“If you want to make a Western cheaply, you just don’t put in any action. You shoot it in front of a wagon and have your actors sit around a fire and talk. Or you shoot through a wagon wheel and have a few Indians go by.

“But if you go out on location and shoot real action, as we do, that alone costs $20,000 a day.”

He may assemble Baca and Slaughter segments for release as theater fare abroad. Zorro is definitely slated for such treatment. But in general Disney is opposed to transferring his strictly-TV characters to U. S. theater screens. Dave Crockett? “The theaters begged for Crockett,” he said.

He sees advantages and disadvantages to the switch from Wednesday at 7:30 to Fridays at 8.

“There were a lot of letters opposing Wednesdays because it interfered with Boy Scouts, Christian Endeavor meetings and various church functions.

“On the other hand, I opposed the later hour, because there's the problem of kids staying up, and the kids control the dials. But it was pointed out that, with no school next day, they can stay up later Fridays. My brother, Roy, was concerned, too, because he felt Friday was a theater night, and it wasn’t fair to theater owners.

“We didn’t try to get away from competition. There’s always competition. And sometimes it’s too bad.

“One of my favorites is Groucho Marx. I didn’t want ‘Zorro’ scheduled against him, but I had no say in the matter.

“I saw Groucho once, and he told me his daughter came to him and asked, ‘Daddy, do I have to look at you?’ Groucho replied, ‘This is a free country.’ ‘So she turned on “Zorro,”’ Groucho said, ‘and I watched it from the background myself!’”

Labels:

Walt Disney

Friday, 22 December 2017

Mistletoe Bait

Jack Zander animates one of my favourite sequences in a Tom and Jerry cartoon in The Night Before Christmas. It’s when Jerry holds out the mistletoe to try to con Tom into giving him the traditional kiss. It works. Then Jerry kicks his the cat’s butt into the air.

There isn’t a huge range of emotions but just enough to make the scene charming.

Zander left for war service and when he got out, worked in New York City for Willard Pictures, and then Transfilm before opening his own commercial studio(s) on the East Coast. He died five months short of his 100th birthday in 2007.

There isn’t a huge range of emotions but just enough to make the scene charming.