After network TV made its huge expansive leap in 1948, ad agencies moved their money from radio into the new medium. On radio, sponsors could get away with an announcer reading straight copy. TV needed more. And an awful lot of agencies picked animation as the easiest and cheapest way to get their messages across.

But the studios contracted to make the animated commercials for the agencies decided the designs used in theatrical cartoons were all wrong. They went for flatter, stylised characters, just like newspaper comics and magazine panels; the UPA studio was doing the same thing in its theatricals. A lot of the cartoon commercials were clever and entertaining and won awards. And that’s when one old theatrical studio decided it wanted a chunk of all this commercial moolah.

Terrytoons had been run by Paul Terry since its inception in 1929 (though Terry managed to manoeuvre Frank Moser out of a partnership a few years later) until he sold the studio to CBS on January 9, 1956. The network now had a stash of old cartoons it could run, but to grow it had to move into new fields. And because it was looking at advertising, it hired one of the young commercial award-winners praised in the trades—Gene Deitch.

Deitch joined the Jam Handy Organization in Detroit as its chief animator in November 1949. He jumped to UPA in New York and found himself winning awards and in demand. He joined Storyboard Productions as creative director in September 1955, moved to Robert Lawrence Productions the following March and then was hired by CBS to be the creative supervisor at Terrytoons in June, a new post that supposedly made him the creative boss.

One can only imagine the atmosphere at Terrytoons with someone from the outside being brought in. In television, that means change. And Weekly Variety of August 15, 1956 outlined Deitch’s ambitious plan.

CBS Full of Animation, Projecting Terrytoons Into TV Programming“New styles of animation and new characters” meant the old styles and characters were o-w-t OUT (that includes old gags like the one you just read). Deitch’s approach to commercials was modern. Terrytoons’ theatrical shorts were anything but. The cartoons of 1955 looked and sounded like the cartoons of 1940 and had become repetitious; if you’d seen one Mighty Mouse/Oil Can Harry operetta, you’d pretty much seen them all. But many people like staying in their comfort zones and don’t like “new” or “different.” Deitch may have been the “creative boss” but he soon became the subject of office politics, which included a lack of support from the people above him. By early June 1958, Deitch found himself o-w-t, and corralled a job as consulting art director with Robert Davis Productions before forming his own company.

With most of the stock-taking and inventorying how complete since CBS purchased Terrytoons for $5,000,000 at the beginning of the year, the New Rochelle animation plant is swinging into a diversified and fullscale production effort that will embrace television programming, special effects for video, tv animated commercials on a open-to-all basis and continuation of theatrical cartoons for 20th-Fox distribution.

Under exec producer Gene Deitch, former UPA exec who recently took over the creative chores at Terrytoons, the hottest project in the works at the CBS subsid is a new series of children’s cartoons under the title of a new character, “Tom Terrific.” Current plans—project is in the pilot stage—are to produce five four-minute cliff hanger episodes for each story, for initial use on the CBS-TV “Captain Kangaroo” morning kidshow. Under such a formula, the five episodes could then be combined and edited into a 15-minute program for use on other kidshows and eventual syndication through CBS television Film Sales. Number of such 15-minute shows would depend on the reaction to the strip showings on “Kangaroo.” Series is an adventure story, with the title character being a little boy who can turn into anything he wants to be. Allan Swift is doing the voices [note: Lionel Wilson actually provided all the voices on the series].

First evidence of the subsid’s new work for television, however, will be seen next Sunday (19) on the Ed Sullivan show, for which Terrytoons has created eight one-minute animated introductions.

Sullivan has indicated he’d like to experiment some more in this direction. The introes will concern Sullivan’s international search for talent, in keeping with the general theme of Sunday’s show, "Sullivan’s Travels,” but if these click, some more with other themes will be ordered.

On the commercial side, Deitch said Terrytoons would attempt to concentrate on “comedy commercials” a la Bert & Harry commercials for Piel’s Beer, on which Deitch worked while at UPA and which in his opinion proved that comedy can sell goods. There are already a number of clients in the house, and Terrytoons has already developed one new character, “P.J. Tootsie,” described as a hearty, “Eddie Mayehoff type guy who’s dedicated to the making of Tootsie Rolls.” Client is Sweets Co. of America.

In work now are nine Cinema-Scope shorts for theatrical use by 20th-Fox, a continuation of the longtime 20th-Terrytoons relationship. It probably marks the first time a network operation is producing for the theatre in collaboration with a major studio. Deitch said his staff is working on the development of new styles of animation and new characters. One step in the creation of such styles and characters was the hiring this week of Ernie Pintoss [sic] as director of research and development, a new post for Terrytoons and possibly for any syndication house. Pintoss had been working with UPA as director of the new UPA series in production for CBS-TV.

An improbable adventure began for Deitch in October 1959. He was hired by Rembrandt Films’ William L. Snyder for what was supposed to be a 10-day job examining operations at a cartoon studio in Prague, Czechoslovakia. In the meantime, Snyder jumped in bed (figuratively) with Al Brodax of King Features, who was looking to put the company’s characters in cut-rate cartoons on TV. It was looking to air a half-hour show called Cartoon Omnibus, to be emceed by The Little King, who never talked in the newspaper comics. Here’s what Weekly Variety had to say about the show on July 6, 1960:

A Two-Continent CartoonerySampson, apparently correctly spelled as “Samson Scrap,” never made it into a series. You can read more about the cartoon on Jerry Beck’s Cartoon Research web site. Format Films, incidentally, won the contract to product the other elements of the Omnibus pilot.

Upsurge of cartoon production for tv has necessitated a two-continent cartoonery operation, according to William L. Snyder, prez of Rembrandt Films. Rembrandt has a deal with King Features for the production of new “Popeye” cartoons and an original, titled “Sampson Scrap and Delilah.” The two Continent operation finds Rembrandt doing the storyboards and soundtrack in the U.S. and animation and shooting in Europe.

Snyder said that doing the animation and shooting in Europe initially was motivated by cost savings. But it’s no longer less expensive, he stated, adding that there just isn’t enough cartoon art talent around in the U.S. to meet the demand and even the European pool is being severely taxed. Rembrandt has ties in Zurich, Switzerland, and Milan. Snyder left at the weekend for London, where he hopes to establish additional production facilities.

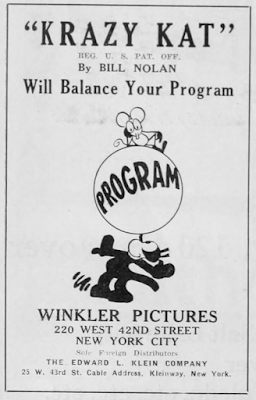

He also will visit Zurich to oversee production there. “Sampson Scrap” was created by Gene Deitch, formerly with UPA and Terrytoons, and Allen Swift, emcee of “Popeye” show on WPIX, N. Y. Deitch directs and Swift does all the voices. “Sampson” will be one of the strips in a half-hour show, the others being “Barney Google and Snuffy Smith” and “Krazy Kat.”

King Features, under its “Popeye” program, has a policy of parcelling out production. Rembrandt will do 16 episodes, with episodes due to coming in starting next month. “Sampson” footage will be coming off the beltline in the fall.

Then Daily Variety announced on March 9, 1961 that Snyder had secretly inked a deal with MGM six months earlier to revive Tom and Jerry cartoons for theatres, and they were already in production, with the first one scheduled for release on May 3rd. While all this was going on, Deitch had teamed with Jules Feiffer and Al Kouzel to win an Oscar in April 1961 for the animated short “Munro.”

MGM decided to hand the Tom and Jerry contract to Walter Bien and Chuck Jones in August 1963. Deitch continued animating in Prague, winning esteem for his work on children’s stories, and being featured in retrospectives of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and by ASIFA in Los Angeles.

Here’s a United Press International story from June 22, 1974 where Deitch is interviewed about his career to date.

Cartoon Director Gives Short Subjects ‘Tender Loving Care’Deitch’s 10-day journey to Prague in 1959 continues to this day. It is there he is celebrating his 91st birthday today as cartoon fans look back at his accomplishments. For someone who became part of a dying industry years ago, he’s accomplished a lot.

By RICHARD C. LONGWORTH

PRAGUE (UPI) – Gene Deitch probably is the most prominent non-Communist American living permanently in Eastern Europe, which is quite a switch for a man who used to direct Terrytoons cartoons.

When he first came to work in Prague, he had never been in Europe, was “completely confused” and held a contract that allowed him to go home to New York any time he wanted.

That was 15 years ago. The Oscar-winning American cartoon director is still here—living in a modern flat beside the Moldau River with his Czech wife and happily making “polished little gems” for American schools.

“Sometimes it takes us one year to make a six-minute film,” the Chicago-born, California-reared Deitch said. “You can’t do that in America. Nobody can afford to put the time into little things.

“At my stage, I’m not trying to win any more Oscars. Instead we give each cartoon tender loving care. “The luxury of living in Europe is that I don’t have to make so much money. I’m earning a lot less than in New York, but I have a lot more in the bank.

“And I can believe in the films I’m making now,” said the man who used to turn out commercials and “Popeye” cartoons by the dozen. “That’s the key to my own happiness.”

Deitch, 49, began his unique odyssey in 1959. when he was 34 and had his own firm in New York. He had been creative director with Terrytoons, had made the Bert and Harry Piel beer commercials for television, had a wife, three children, a big house in the suburbs and a high salary.

“I was headed for a heart attack,” he says now.

Then entered William L. Snyder, an American cartoon entrepreneur who had bought films for years from a top-flight Prague studio and now wanted the Czechs to make films for the U.S. market from American children’s books. Snyder needed an American director in Prague to give the films the zip and pace American audiences demand and to act as liason with the Czechs. He asked Deitch to take the job.

“It was an offer I couldn’t refuse,” Deitch said. “But I had barely heard of Czechoslovakia and the contract I signed gave me every kind of out.”

When he arrived, Zdenka, the young Czech woman in charge of Snyder’s films, was so hurt at the outside interference that she refused to meet him at the airport.

“But I felt I had as much to learn from her as she did from me. And after the first week Zdenka said to me, ‘If you like going shopping, I go with you.’

“The next Wednesday night we had dinner and fell in love. We were both married, and this really opened up a great set of problems for both of us.” Deitch also had fallen in love with dark, romantic old Prague.

He and Snyder signed a seven-year contract, enabling him to stay in Prague to make “Tom and Jerry” and “Popeye” cartoons. He and Zdenka married in 1964.

Deitch, a trim, excitable man with thinning brown hair and steel-rimmed glasses, let the Snyder contract lapse and now works mostly on contract from Weston Woods Studios of Weston, Conn., directing cartoons—largely adapted from children’s books—for American schools.

He is employed by his American clients, not by the Czechs.

“Zdenka and I have some fiery battles at the studio. She’s the boss—the production manager. I’m her client. It’s her duty to stick to the contract and to keep me in line. It’s my job to get as much for my client’s money as possible.”

A small flat beside the Charles Bridge has been Deitch’s home for seven years. It is jammed with sound equipment, children’s books and many of the awards his 1,000 plus films have won. The couple also has a country house, which they are renovating with tools Deitch won by entering a design for hollow chopsticks—“for sucking up wonton soup”—in a British inventors’ contest.

Despite his success and stability here, “I can’t get over a temporary feeling,” Deitch said.

“The key to my success here is that I do my work and cause no trouble. I have my opinions but I don’t noise them around. They know I’m not a Communist, but they also know I’m not a troublemaker.

“I’m an American, but it’s not incumbent on me to write an expose of life in Czechoslavakia. We’ve got Watergate. Who am I to write about what’s wrong here. I’m a guest in their country.

“There’s a lot of things we have that they don’t,” he said, looking out of his window, across the old roofs and quiet courtyards towards the medieval alchemist’s tower beside the Moldau. “I get very confused now about which is the best way of life. The line is not so easy to draw any more.”

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)