Bugs Bunny’s in for a shock when he checks the sheet music in Rhapsody Rabbit.

What I didn’t notice until reader N. Pozega pointed it out was the comic instructions over the bars of music. “Slow Polka.” “Hurry Here.” “Goulashio” and, of course, “Dow Jonesissimo.”

Terry Lind was the background artist on this short, but I don’t know if she drew the sheet music.

The official release date was November 9, 1946, but it played at the RKO Orpheum in Davenport, Iowa on Thursday, Oct. 24th (with Rosalind Russell in Sister Kenny).

Monday, 20 March 2023

Sunday, 19 March 2023

Creating Jack Benny

Jack Benny went from a man whose comedy had never been done before, to a man whose comedy had always been done before.

Jack Benny went from a man whose comedy had never been done before, to a man whose comedy had always been done before.

Benny starred in his own radio show in 1932. Canada Dry was his sponsor. If they thought they were buying Jack’s old vaudeville routines, they were mistaken. Benny got laughs by making fun of his sponsor. The sponsor wasn’t altogether happy about being ridiculed and Benny was sent packing within a year (after a failed attempt to foist a new writer on him).

Jack and his writers, over the years, then evolved a series of characters and situations—eventually so numerous, they could play mix and match and call on them at any time. By the time Benny was cruising along in television in the ‘50s, he continually dragged out his old routines, sometimes slightly reworking huge portions of old radio scripts. It had been done before, but still got laughs.

Here’s a syndicated story explaining how the show was put together for weekly television. It appeared in papers as early as Sept. 9, 1960. The photo below accompanied the article. The irony is Mary Livingstone was no longer part of show. She refused to go on camera, though Jack was able to cajole her to appear on very rare occasion. Mary developed into a fine comedienne, at least within the context of the Benny oeuvre, but stage fright overcame her as time went on. Jack stays in character at the end.

Jack Benny Reveals Secrets of Survival

Avoiding Bad Taste Policy in TV Shows

Editor's Note: This article was written for the North American Newspaper Alliance by a veteran of the entertainment world and one of its top stars who gives much credit for his success to his writers and to the insistence that nothing of an offensive nature must appear on his television shows.

By JACK BENNY

ANYONE who has been around the broadcasting business as long as I, and continually employed at that, rates a job in the government’s Civil Defense Agency. He knows all there is to know about survival!

Last autumn my gang and I returned for an 11th season of television. Since you don’t have your second year of life (something which has always confused me) our first show was in effect the 10th anniversary of our video debut. Of course, it was many years prior to that that my good friend, Ed Sullivan, introduced me to broadcasting. I was an experienced vaudevillian at the time and had won some recognition in major Broadway musicals.

Ed put me on his radio show and as I stood there before that pugnacious microphone my first broadcast words were:

“Hello folks. This Is Jack Benny. There will be a slight pause for everyone to say ‘Who cares?’ "

The fact that people cared then and have cared enough since to keep our program going through close to 1,000 radio and television broadcasts is largely a tribute to my writers.

Ad Libs Not Answer

Fred Allen once told me "You couldn’t ad lib a belch after a Hungarian dinner.” Well I don’t know about that. I’ve done some rather wonderful things after Hungarian dinners.

Nevertheless unless, you are a genius— which I am not — or the luckiest man alive, you cannot survive long in this business relying on ad libs alone. Allen was pretty good at It — he once said I was the only violinist who makes you feel the strings would sound better back in the cat— but even Fred, the comedians’ comedian, had his troubles with TV.

You survive and prosper in this profession by preparedness—and my best “ad libs” are those my writers and I have worked on a long time.

When I was a youngster starting out as the only knickerbockered member of the pit orchestra at the Barrison Theater in Waukegan, comedians could break in their acts in the small time and gradually improve the material as they profited by audience reaction. But this electronic stage we operate on today is different. You need a new act every time you’re on— and there is no opportunity to be lousy.

Long-Time Associates

I have four writers and they've all been with me a long time. When I want the “new boys," for example, I ask for Hal Goldman and Al Gordon. They’ve been with me only 10 years. Sam Perrin and George Balzer are in their 18th year. Of course, I’m a guy who believes in togetherness. Don Wilson and Rochester have been around almost as long as I and Mahlon Merrick has been my musical director 25 years.

I have a suite of offices in Beverly Hills and the writers have a big room there, complete with coke, coffee and cigarette vending machines so they won’t have to go out for a coffee break. As you can see, their comfort is uppermost in my mind.

We don’t keep track of who comes up with what bit of funny business. None of us cares who creates which joke and, anyhow, usually we’re all talking at once while a secretary tries to take verbatim notes. Naturally, she can only transcribe those words she hears. Since we all occasionally outshout the other, the result is a pretty good mixture of all our thoughts.

We start with a situation premise for a show and go on from there. While we make changes and improvements right up to the moment of putting the show on film or tape, this can’t be construed as deadline writing because we work on scripts many weeks ahead.

If we have one guiding policy, it is to avoid bad taste. Let me give you an example. I think the so-called school of “sick comedy" is atrocious. I don’t like jokes about Buchenwald or what happened at the theater the night Lincoln was killed I don’t use material which seeks a laugh at the expense of somebody rise's grave misfortune. You can learn a lot of things In this business but you can’t learn good taste Either you have it or you haven’t.

Show Preparations

I’ve said that my writers and I huddle first to decide on a story premise. Then they go to work on the first of several script drafts. I edit the material, suggest additions and changes. Finally as the date of broadcast approaches, we call in all the members of the cast and read the script aloud in my office — each doing his own part. This gives us an approximate idea of timing and also an Indication of where doctoring is needed.

Everyone goes home and memorises his lines—we don’t use teleprompters or “idiot cards.” Two days later we start two days of intense rehearsal and the third day we put the show on film or tape. The writers are present through the entire operation and contribute refinements up to the second the cameras function.

This year we are doing a show every Sunday night. In that initial TV season a decade ago, I did only four programs. The next year we did six, then ten, and the last few years we were on every other week. But a weekly show is easier for me because we can use running gags and anyhow once our steam Is up we roll.

I suppose if anyone were to ask the secret of our success I’d have to say we work hard— and don’t try to reach for the moon. You cannot have a blockbuster every week. You cannot expect to be on fop of every popularity poll.

Try to Amuse

We try never to be lousy. That way we are frequently quite funny. We seek to amuse. And it isn’t simple. The writers must produce every week.

This means I must keep them in good humor and never offend them.

I lean over backwards to do this. For Instance, a few years ago when Al Gordon, the youngest of my writers, had been with me only a relatively short time, he nagged me into betting $20 the New York Giants would win the world series. Cleveland was AI's choice. I’m not much of a gambling man but Al was insistent.

Well, the Giants won the first game and Al insisted on paying me. But I didn’t want to take his money— he had a child and a new home. So I suggested we bet double or nothing on the second game. That night I was $40 ahead.

Now I was really In a quandary. If I took his money I’d feel guilty. And If I didn’t he’d be offended. So we double-or-nothinged again. Surely It was now Cleveland’s turn to win a game.

Well, you know what happened. New York won in four straight and I ended up with $160.

Which only goes to prove that considerate treatment of others always pays off.

Labels:

Jack Benny

Saturday, 18 March 2023

A Little Lundy

In the Disney lore, Dick Lundy was the one who came up with the quintessential Donald Duck, angry and ready to fight, hopping up and down with his fist extended.

Lundy was an early employee of Walt Disney, hired in July 1929. Among his other accomplishments for the studio was animation on The Three Little Pigs and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (he received no bonus money for the latter). Despite his loyalty during the studio strike in 1941, Lundy was fired by Disney in October 1943. Animator Fred Kopietz told author Michael Barrier that Uncle Walt was looking out the window and wouldn’t face Lundy, who wanted to know what his next assignment for the studio was. The assignment was to pick up his final pay. Several weeks later, his career took him to Walter Lantz. Lundy followed with stops at MGM and, after a period working on commercial and industrial films, starting with Dudley TV Corp. in 1951, Hanna-Barbera.

Some fans say the Lantz cartoons were the most attractive during Lundy’s directorial reign in the last half of the ‘40s. He had a fine group of animators, some from Disney, and his classical music cartoons were top notch. He once remarked how, at Lantz, he favoured personality animation over gags. Lundy seems to have liked his time at Lantz, leaving only because the studio shut down. He told author Joe Adamson: “Walter Lantz is the type that falls into a cesspool and comes out smelling like three lilies. No matter what he does, whether it’s right or wrong, it seems to work out for him. You can call it what you want. I call it luck.”

Some fans say the Lantz cartoons were the most attractive during Lundy’s directorial reign in the last half of the ‘40s. He had a fine group of animators, some from Disney, and his classical music cartoons were top notch. He once remarked how, at Lantz, he favoured personality animation over gags. Lundy seems to have liked his time at Lantz, leaving only because the studio shut down. He told author Joe Adamson: “Walter Lantz is the type that falls into a cesspool and comes out smelling like three lilies. No matter what he does, whether it’s right or wrong, it seems to work out for him. You can call it what you want. I call it luck.”

Lundy took over Tex Avery’s unit at MGM during Avery’s extended time off, mainly directing Barney Bear cartoons. He was hired as an animator at H-B to work on both the Huckleberry Hound and Quick Draw McGraw shows (he was one of the animators of Snuffles).

Here’s a feature story on Lundy from the Banner-Press of David City, Nebraska, June 15, 1981. His explanation about Mickey Mouse is, well, interesting. Soundman Jimmy MacDonald took over as the voice of Mickey, so the claim about Walt and a lack of time doesn’t ring true.

Donald Duck, Woody Woodpecker animator visits daughter in county

By Jim Reisdorff

Special Correspondent

Dick Lundy is responsible for making Donald what he is today— a tempermental duck.

The former animator for such big-name cartoon animation production companies as Walt Disney and Hanna Barbara made a private visit to this area last week. Lundy and his wife, Mabel, from Vista, Ca., visited with their son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. John McFadden of Brainard.

Those who grew up watching cartoons in moviehouses and on television are likely familiar with such characters as Woody Woodpecker, Andy Panda, Yogi Bear and Fred Flintstone. Less well known are the actual people, such as Lundy, whose drawing and directing talents brought these loveable creatures to screen life.

Lundy retired in 1974 after 45 years in animation. He started with the Walt Disney studios in California in 1929. “There were 17 employees at Disney when I started, and that included Roy (Walt’s brother) and the janitor,” said Lundy. He added this later grew to where Disney employed over 1,600.

Lundy’s original work at Disney was as one of the actual animators. They drew the frame-by-frame film action of the characters that was then speeded up to give an impression of physical motion. He later directed the plotline and action of full-length Disney cartoon films as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

Donald Duck first appeared as a minor character in the cartoon short “The Wise Little Hen.” Lundy said he was appointed to animate Donald's action in the next film called “Orphan's Benefit.” The scenario called for Donald to appear on stage and recite “Mary Had a Little Lamb” while the audience heckled him. Lundy then devised Donald’s temper tantrum characteristics of flailing his fists, jumping up and down, while quacking incoherently. This proved so popular that Donald was then given his own cartoon series.

Lundy noted the raspy (and now popularly imitated) voice of Donald was done by Clarence Nash, a milkman whose voice talent was discovered by Disney.

The “stardom” of Donald Duck didn’t exactly mean the popularily decline of Disney ’s original character, Mickey Mouse, although Donald was then used in more cartoons than Mickey, said Lundy. Walt Disney insisted on personally doing Mickey's squeaky voice. So because of Disney's busy schedule in studio managing, Mickey's film appearances were limited in later years to special occasions.

Lundy described the late Walt Disney as being “your typical artist-genius.” But disagreements with Disney caused Lundy to quit in 1943 and join the Walter Lantz productions. Lantz’s most famous creation which Lundy helped animate was a wood pecker with the "Ha-Ha-Haa-Ha’’ cry.

Lundy described the late Walt Disney as being “your typical artist-genius.” But disagreements with Disney caused Lundy to quit in 1943 and join the Walter Lantz productions. Lantz’s most famous creation which Lundy helped animate was a wood pecker with the "Ha-Ha-Haa-Ha’’ cry.

After five years with Lantz, Lundy briefly joined the M G-M Movie Studio animation department. He then worked on the Lucille Ball Show staff by making animated caricatures of Lucy and Desi Arnez [sic] which introduced the Phillip Morris cigarette commercials in the show.

Animation-making was becoming extremely expensive by this time, said Lundy. In 1958 he joined the animation partners of Hanna and Barbera, who had developed a "limited animation” technique of cartoons directly for television. Lundy finished his active animation work with Hanna Barbera which continues, to supply Saturday morning cartoon watchers with characters as the Flintstones and Scooby-Doo.

He hasn’t been inside a movie theater in 10 years, but Lundy admitted to occasionally turning on the afternoon TV children's matinee, "out of curiosity more than anything else,” to see if they're still showing the cartoons he worked on.

Mrs. John (Divianna) McFadden added she also watches cartoon re-runs to see if she can pick out her dad’s name in the credits. Mrs. McFadden works for the Nebraska Department of Education in Lincoln as a supervisor in the special education department.

Richard James Lundy was born Aug 14, 1907 in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan. His father James S. Lundy was an adding machine inspector. His parents lived in Detroit soon after his birth, divorced when he was 12 and his mother Minnie raised him on a waitress' salary. After arriving in California, he found work as a bank teller before being hired at Disney.

Dick Lundy retired to San Diego, where he died on April 7, 1990 at the age of 82.

Lundy was an early employee of Walt Disney, hired in July 1929. Among his other accomplishments for the studio was animation on The Three Little Pigs and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (he received no bonus money for the latter). Despite his loyalty during the studio strike in 1941, Lundy was fired by Disney in October 1943. Animator Fred Kopietz told author Michael Barrier that Uncle Walt was looking out the window and wouldn’t face Lundy, who wanted to know what his next assignment for the studio was. The assignment was to pick up his final pay. Several weeks later, his career took him to Walter Lantz. Lundy followed with stops at MGM and, after a period working on commercial and industrial films, starting with Dudley TV Corp. in 1951, Hanna-Barbera.

Some fans say the Lantz cartoons were the most attractive during Lundy’s directorial reign in the last half of the ‘40s. He had a fine group of animators, some from Disney, and his classical music cartoons were top notch. He once remarked how, at Lantz, he favoured personality animation over gags. Lundy seems to have liked his time at Lantz, leaving only because the studio shut down. He told author Joe Adamson: “Walter Lantz is the type that falls into a cesspool and comes out smelling like three lilies. No matter what he does, whether it’s right or wrong, it seems to work out for him. You can call it what you want. I call it luck.”

Some fans say the Lantz cartoons were the most attractive during Lundy’s directorial reign in the last half of the ‘40s. He had a fine group of animators, some from Disney, and his classical music cartoons were top notch. He once remarked how, at Lantz, he favoured personality animation over gags. Lundy seems to have liked his time at Lantz, leaving only because the studio shut down. He told author Joe Adamson: “Walter Lantz is the type that falls into a cesspool and comes out smelling like three lilies. No matter what he does, whether it’s right or wrong, it seems to work out for him. You can call it what you want. I call it luck.”

Lundy took over Tex Avery’s unit at MGM during Avery’s extended time off, mainly directing Barney Bear cartoons. He was hired as an animator at H-B to work on both the Huckleberry Hound and Quick Draw McGraw shows (he was one of the animators of Snuffles).

Here’s a feature story on Lundy from the Banner-Press of David City, Nebraska, June 15, 1981. His explanation about Mickey Mouse is, well, interesting. Soundman Jimmy MacDonald took over as the voice of Mickey, so the claim about Walt and a lack of time doesn’t ring true.

Donald Duck, Woody Woodpecker animator visits daughter in county

By Jim Reisdorff

Special Correspondent

Dick Lundy is responsible for making Donald what he is today— a tempermental duck.

The former animator for such big-name cartoon animation production companies as Walt Disney and Hanna Barbara made a private visit to this area last week. Lundy and his wife, Mabel, from Vista, Ca., visited with their son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. John McFadden of Brainard.

Those who grew up watching cartoons in moviehouses and on television are likely familiar with such characters as Woody Woodpecker, Andy Panda, Yogi Bear and Fred Flintstone. Less well known are the actual people, such as Lundy, whose drawing and directing talents brought these loveable creatures to screen life.

Lundy retired in 1974 after 45 years in animation. He started with the Walt Disney studios in California in 1929. “There were 17 employees at Disney when I started, and that included Roy (Walt’s brother) and the janitor,” said Lundy. He added this later grew to where Disney employed over 1,600.

Lundy’s original work at Disney was as one of the actual animators. They drew the frame-by-frame film action of the characters that was then speeded up to give an impression of physical motion. He later directed the plotline and action of full-length Disney cartoon films as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

Donald Duck first appeared as a minor character in the cartoon short “The Wise Little Hen.” Lundy said he was appointed to animate Donald's action in the next film called “Orphan's Benefit.” The scenario called for Donald to appear on stage and recite “Mary Had a Little Lamb” while the audience heckled him. Lundy then devised Donald’s temper tantrum characteristics of flailing his fists, jumping up and down, while quacking incoherently. This proved so popular that Donald was then given his own cartoon series.

Lundy noted the raspy (and now popularly imitated) voice of Donald was done by Clarence Nash, a milkman whose voice talent was discovered by Disney.

The “stardom” of Donald Duck didn’t exactly mean the popularily decline of Disney ’s original character, Mickey Mouse, although Donald was then used in more cartoons than Mickey, said Lundy. Walt Disney insisted on personally doing Mickey's squeaky voice. So because of Disney's busy schedule in studio managing, Mickey's film appearances were limited in later years to special occasions.

Lundy described the late Walt Disney as being “your typical artist-genius.” But disagreements with Disney caused Lundy to quit in 1943 and join the Walter Lantz productions. Lantz’s most famous creation which Lundy helped animate was a wood pecker with the "Ha-Ha-Haa-Ha’’ cry.

Lundy described the late Walt Disney as being “your typical artist-genius.” But disagreements with Disney caused Lundy to quit in 1943 and join the Walter Lantz productions. Lantz’s most famous creation which Lundy helped animate was a wood pecker with the "Ha-Ha-Haa-Ha’’ cry.After five years with Lantz, Lundy briefly joined the M G-M Movie Studio animation department. He then worked on the Lucille Ball Show staff by making animated caricatures of Lucy and Desi Arnez [sic] which introduced the Phillip Morris cigarette commercials in the show.

Animation-making was becoming extremely expensive by this time, said Lundy. In 1958 he joined the animation partners of Hanna and Barbera, who had developed a "limited animation” technique of cartoons directly for television. Lundy finished his active animation work with Hanna Barbera which continues, to supply Saturday morning cartoon watchers with characters as the Flintstones and Scooby-Doo.

He hasn’t been inside a movie theater in 10 years, but Lundy admitted to occasionally turning on the afternoon TV children's matinee, "out of curiosity more than anything else,” to see if they're still showing the cartoons he worked on.

Mrs. John (Divianna) McFadden added she also watches cartoon re-runs to see if she can pick out her dad’s name in the credits. Mrs. McFadden works for the Nebraska Department of Education in Lincoln as a supervisor in the special education department.

Richard James Lundy was born Aug 14, 1907 in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan. His father James S. Lundy was an adding machine inspector. His parents lived in Detroit soon after his birth, divorced when he was 12 and his mother Minnie raised him on a waitress' salary. After arriving in California, he found work as a bank teller before being hired at Disney.

Dick Lundy retired to San Diego, where he died on April 7, 1990 at the age of 82.

Labels:

Hanna-Barbera,

MGM,

Walt Disney,

Walter Lantz

Friday, 17 March 2023

Piccolos and Birds

Van Beuren’s cartoonists just didn’t have it in them in 1932.

Walt Disney had raised the bar for animation with Flowers and Trees and the Disney shorts starting looking more polished with more sophisticated animation. Audiences loved it.

Other studios tried the same thing. Van Beuren’s Feathered Follies (1932) has singing, dancing animals and nature settings, all Disney elements. The drawing is far more primitive-looking that what Walt’s people put on the screen (though better than the Aesop’s Fables that emerged immediately after sound came in). But I don’t care. There’s always some weirdness in a Van Beuren cartoon that I find appealing.

Here’s a really fun design for a bird, which scoops up a caterpillar in its mouth and plays it like an accordion before swallowing it. The song Piccolo Pete is on the soundtrack. I know this song was in another Van Beuren cartoon (a Cubby Bear short?) but I can’t find the reference. Someone here will know because Tralfaz readers are smart.

Check out this bird with flute piccolo holes in its beak.

Unfortunately, the cartoon missed a chance to do the four-conjoint-mouths-singing gag, a Van Beuren speciality.

And I don’t care what studio it is, I like this gag. A bird walks along the top wire of a fence which turns into a bar of music, with a vine forming a treble clef. The notes become birds and fly away.

The soundtrack includes “I Ain’t Got Nobody” sung by Margie Hines as a worm and Cal De Voll’s “The Whippoorwill” over the opening credits, listing John Foster, Harry Bailey and music man Gene Rodemich. Here’s a neat version of the main tune.

Walt Disney had raised the bar for animation with Flowers and Trees and the Disney shorts starting looking more polished with more sophisticated animation. Audiences loved it.

Other studios tried the same thing. Van Beuren’s Feathered Follies (1932) has singing, dancing animals and nature settings, all Disney elements. The drawing is far more primitive-looking that what Walt’s people put on the screen (though better than the Aesop’s Fables that emerged immediately after sound came in). But I don’t care. There’s always some weirdness in a Van Beuren cartoon that I find appealing.

Here’s a really fun design for a bird, which scoops up a caterpillar in its mouth and plays it like an accordion before swallowing it. The song Piccolo Pete is on the soundtrack. I know this song was in another Van Beuren cartoon (a Cubby Bear short?) but I can’t find the reference. Someone here will know because Tralfaz readers are smart.

Check out this bird with flute piccolo holes in its beak.

Unfortunately, the cartoon missed a chance to do the four-conjoint-mouths-singing gag, a Van Beuren speciality.

And I don’t care what studio it is, I like this gag. A bird walks along the top wire of a fence which turns into a bar of music, with a vine forming a treble clef. The notes become birds and fly away.

The soundtrack includes “I Ain’t Got Nobody” sung by Margie Hines as a worm and Cal De Voll’s “The Whippoorwill” over the opening credits, listing John Foster, Harry Bailey and music man Gene Rodemich. Here’s a neat version of the main tune.

Labels:

Van Beuren

Thursday, 16 March 2023

If It Worked At Warner Bros....

Fans of Tex Avery’s cartoons at MGM likely know he took ideas he used at Warner Bros. and incorporated them into shorts at his new locale.

An example is the silhouettes of audience members moving in front of the action on the screen, like the camera is at the back of a theatre shooting the action, including the film that’s being projected. You can see it in Avery’s Little Red Walking Hood, Daffy Duck and Egghead and Thugs With Dirty Mugs.

Here’s a version in Who Killed Who?, a 1943 MGM cartoon with Billy Bletcher as the voice of a detective who bursts into a room in a creepy mansion after its occupant (Kent Rogers doing his Richard Haydn voice) is killed.

“Everybody stay where you are! Don’t nobody move!” he shouts as we see a silhouette of an audience member get up and move “across the row.”

The detective takes care of things.

“That goes for you, too, bud!” he yells at the figure writhing in head pain.

And the cartoon carried on.

No animators are credited. Just Avery.

An example is the silhouettes of audience members moving in front of the action on the screen, like the camera is at the back of a theatre shooting the action, including the film that’s being projected. You can see it in Avery’s Little Red Walking Hood, Daffy Duck and Egghead and Thugs With Dirty Mugs.

Here’s a version in Who Killed Who?, a 1943 MGM cartoon with Billy Bletcher as the voice of a detective who bursts into a room in a creepy mansion after its occupant (Kent Rogers doing his Richard Haydn voice) is killed.

“Everybody stay where you are! Don’t nobody move!” he shouts as we see a silhouette of an audience member get up and move “across the row.”

The detective takes care of things.

“That goes for you, too, bud!” he yells at the figure writhing in head pain.

And the cartoon carried on.

No animators are credited. Just Avery.

Labels:

MGM,

Tex Avery,

Warner Bros.,

Who Killed Who

Wednesday, 15 March 2023

How Green Acres Survived

Television critics in the 1960s tended to lump together shows where characters spoke with country-fied accents. But they generally didn’t really have anything in common. No one would mistake Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. for The Beverly Hillbillies.

Even the three Filmways “rural” shows on CBS—Hillbillies, Petticoat Junction and Green Acres—were dissimilar. Despite an attempt to locate them together geographically, which always struck me as an attempt to import Hillbillies’ huge audience, only one was set on a farm.

And Green Acres’ atmosphere was entirely different. It was filled with odd denizens and surreal, unexplainable situations that were treated as normal life by everyone but the confused Oliver Wendell Douglas. Grocery store owner, and reality anchor, Mr. Drucker never questioned it. Even Oliver’s sophisticated, Park Avenue-loving wife Lisa settled in and developed her own brand of illogic that meshed with the Hooter(s)ville folk. Only the setting made it rural. The tone could have come from one of those “Behind the Eight Ball” shorts that Richard Bare directed at Warner Bros. before his time behind the cameras on Green Acres.

Here’s a bit of background behind the show. This appeared in papers from October 22, 1966 onward, when Green Acres was into its second season.

Don’t Under Estimate Corn

By BOB THOMAS

AP Movie-Television Writer

HOLLYWOOD (AP) –Some observers of the television scene drew this lesson from the first Neilsen ratings of the 1965-66 season: Never underestimate the value of corn.

This is the attitude of certain sophisticates who sniff at the fact that among the top 10 shows in audience ratings were such offerings as “Green Acres," “Gomer Pyle,” "The Andy Griffith Show" and “Beverly Hillbillies.”

The most impressive showing among series in the ratings was made by "Green Acres," which captured the No. 3 position below the blockbusting Sunday night movie, "The Bridge on the River Kwai.” Do they grow corn on those "Green Acres”?

"I don’t think so," says Jay Sommers, who created, co-writes and produces the series. "I think it’s a fairly sophisticated show."

Sommers, a rotund, owlish veteran of the gag-writing jungle doesn’t really care what the smart crowd thinks of "Green Acres.” It’s his baby, and as long as the public buys it, that’s all that matters.

The inspiration for the show came from Sommers' boyhood, of which two years were spent on a farm in Greenvale, N.Y. His stepfather went broke trying to earn a living from the soil and the experiences remained with the boy. He capitalized on them with a 1950 radio show, "Granby’s Green Acres,” which starred Gale Gordon and Bea Benaderet, the latter now star of "Green Acres", sister show of “Petticoat Junction.”

When “Green Acres’ went on CBS last season, the original plan was to exchange performers with "Petticoat Junction.”

"We’re getting away from that concept now,” said Sommers. "It’s awfully hard to schedule when the actors will be available, and they are busy enough with their own shows. Besides, I think “Green Acres” should stand on its own feet.”

The series is doing a good job of it. Credit is due Sommers who spends a 12-hour day at General Service Studios, overseeing everything from script to cutting. Despite the rural nature of the show, it is filmed almost entirely on the lot. "The people are important, not the settings," explained Sommers.

The secret of "Green Acres' " success?

"I think it appeals to a basic human urge; everyone would like to buy a farm," Sommers theorized. "And we came up with a brilliant combination in Eddie Albert and Eva Gabor. They work together like a dream.”

A thick Hungarian accent didn’t stop Eva Gabor from giving interviews about her series. Indeed, columnist Hal Humphrey talked to her about it in 1965 and 1968. Read them in this post. He also talked to her in 1966. This story appeared on Sept. 5, 1966.

Eva Gabor Spoils Image

By HAL HUMPHREY

Los Angeles Times Service

HOLLYWOOD, Sept. 5—Eva Gabor, of the Hungarian Gabors, has a particular reason for being happy that her and Eddie Albert's TV show, Green Acres, survived its first season.

“It gives me a chance to spoil my image. Everyone always thinks I am the temperamental actress. I remember the very first time I did a TV show, the producer had a girl standing by to take over. They thought I either wouldn’t show up or would walk out after the first act.”

A similar type of storm signal went up when Eva was signed to play Lisa Douglas in the comfed “Green Acres” series. Besides insisting on the town’s most expensive makeup man and her own hairdresser, Eva held out for the chic Jean Louis to do her wardrobe.

IT WORKED

“But you see? It worked, didn’t it? With Gene Hibbs doing my makeup and Peggy Shannon my hair, I really saved the producer money, because I am always ready. And I don't like to take too much credit, because Jay Sommers and Dick Chevillat write marvelous scrips, but I established this character when I wore a chiffon negligee to chase a chicken across the barnyard.

The scene just described by Eva was in an early episode at the beginning of the season with Lisa trying to adjust to living on the farm her husband, Oliver (Eddie Albert), had just purchased. Instead of the ordinary robe prescribed originally, Eva persuaded the director that if Lisa ever chased chickens at all, it would be in a Jean Louis negligee.

“I know this character,” Eva maintains, "because she is like me. When Lisa wears jeans, I make sure they have diamonds for me to wear with them, and I mean real diamonds. If I know they are real diamonds, then the viewers believe it, too.”

STRIVE FOR QUALITY

When Eva digs in adamantly for such conditions, she does not consider it temperament but a striving for a standard of quality that will benefit everyone concerned. She knew she was running the risk of blowing the whole deal by insisting on Jean Louis gowns, diamonds, etc., and Eva wanted this break of co-starring in her own series. “But, darling,” as she says, “what is a break, if it is not done right?”

And, of course, she is right. In one “Green Acres” episode the past season Eva wore a Jean Louis she had worn few weeks earlier. Within two days she had letters from fans demanding to know, “What happened? Can’t you afford a new dress?”

The only temporary setback Eva encountered in her battle for quality was over a proper dressing room. Her first one was a portable job which even the chickens in “Green Acres” might have declined to roost in.

HAS EVERYTHING

“Ah, but after the first Nielsen rating came in, you should see my dressing room. It has everything! But why not? This lunch you and I are having is the first time I've been out of my house or the studio since June. I don’t go to parties. I have to train like an athlete. But I don’t mind. I adore acting. That is why I am 10 minutes early on the set every morning. Also, what these Hollywood people don't realize, I come from the stage and I have discipline.

“I believe there is such a thing as ‘the show must go on.’ Just yesterday I get word that Jolie, my mother, has fallen getting out of her swimming pool and broken her kneecap in three places, a horrible thing. And on the same day my little dog has a stroke, so I am very worried, but I am on the set working anyway.”

MORALE RISES

Eva’s morale has risen since her husband left his stockbroker's job in New York and moved to Hollywood (he waited for the third Nielsen rating on “Green Acres”). Soon after arriving, he became a vice-president for Filmways, the corporation that produces “Green Acres.”

Only two things have not worked out for Eva according to plan. She dare not wear in private life any of the 160 Jean Louis dresses accumulated from the show, because everyone has already seem them on TV. Second, the hillbilly slang on “Green Acres” is spoiling her not-too-recent mastering of the American idiom. When someone on the set mentioned sex the other day, Eva said, “Don’t kick it.” It took a few seconds for the assembled group to figure out she meant “Don't knock it.”

The second season carried on bizarreness (Lisa’s hen lays square eggs) and sly satire (Arnold the Pig gets a draft notice) and continued to get renewed until 1971 when CBS wiped the show off the schedule after 170 episodes.

Even the three Filmways “rural” shows on CBS—Hillbillies, Petticoat Junction and Green Acres—were dissimilar. Despite an attempt to locate them together geographically, which always struck me as an attempt to import Hillbillies’ huge audience, only one was set on a farm.

And Green Acres’ atmosphere was entirely different. It was filled with odd denizens and surreal, unexplainable situations that were treated as normal life by everyone but the confused Oliver Wendell Douglas. Grocery store owner, and reality anchor, Mr. Drucker never questioned it. Even Oliver’s sophisticated, Park Avenue-loving wife Lisa settled in and developed her own brand of illogic that meshed with the Hooter(s)ville folk. Only the setting made it rural. The tone could have come from one of those “Behind the Eight Ball” shorts that Richard Bare directed at Warner Bros. before his time behind the cameras on Green Acres.

Here’s a bit of background behind the show. This appeared in papers from October 22, 1966 onward, when Green Acres was into its second season.

Don’t Under Estimate Corn

By BOB THOMAS

AP Movie-Television Writer

HOLLYWOOD (AP) –Some observers of the television scene drew this lesson from the first Neilsen ratings of the 1965-66 season: Never underestimate the value of corn.

This is the attitude of certain sophisticates who sniff at the fact that among the top 10 shows in audience ratings were such offerings as “Green Acres," “Gomer Pyle,” "The Andy Griffith Show" and “Beverly Hillbillies.”

The most impressive showing among series in the ratings was made by "Green Acres," which captured the No. 3 position below the blockbusting Sunday night movie, "The Bridge on the River Kwai.” Do they grow corn on those "Green Acres”?

"I don’t think so," says Jay Sommers, who created, co-writes and produces the series. "I think it’s a fairly sophisticated show."

Sommers, a rotund, owlish veteran of the gag-writing jungle doesn’t really care what the smart crowd thinks of "Green Acres.” It’s his baby, and as long as the public buys it, that’s all that matters.

The inspiration for the show came from Sommers' boyhood, of which two years were spent on a farm in Greenvale, N.Y. His stepfather went broke trying to earn a living from the soil and the experiences remained with the boy. He capitalized on them with a 1950 radio show, "Granby’s Green Acres,” which starred Gale Gordon and Bea Benaderet, the latter now star of "Green Acres", sister show of “Petticoat Junction.”

When “Green Acres’ went on CBS last season, the original plan was to exchange performers with "Petticoat Junction.”

"We’re getting away from that concept now,” said Sommers. "It’s awfully hard to schedule when the actors will be available, and they are busy enough with their own shows. Besides, I think “Green Acres” should stand on its own feet.”

The series is doing a good job of it. Credit is due Sommers who spends a 12-hour day at General Service Studios, overseeing everything from script to cutting. Despite the rural nature of the show, it is filmed almost entirely on the lot. "The people are important, not the settings," explained Sommers.

The secret of "Green Acres' " success?

"I think it appeals to a basic human urge; everyone would like to buy a farm," Sommers theorized. "And we came up with a brilliant combination in Eddie Albert and Eva Gabor. They work together like a dream.”

A thick Hungarian accent didn’t stop Eva Gabor from giving interviews about her series. Indeed, columnist Hal Humphrey talked to her about it in 1965 and 1968. Read them in this post. He also talked to her in 1966. This story appeared on Sept. 5, 1966.

Eva Gabor Spoils Image

By HAL HUMPHREY

Los Angeles Times Service

HOLLYWOOD, Sept. 5—Eva Gabor, of the Hungarian Gabors, has a particular reason for being happy that her and Eddie Albert's TV show, Green Acres, survived its first season.

“It gives me a chance to spoil my image. Everyone always thinks I am the temperamental actress. I remember the very first time I did a TV show, the producer had a girl standing by to take over. They thought I either wouldn’t show up or would walk out after the first act.”

A similar type of storm signal went up when Eva was signed to play Lisa Douglas in the comfed “Green Acres” series. Besides insisting on the town’s most expensive makeup man and her own hairdresser, Eva held out for the chic Jean Louis to do her wardrobe.

IT WORKED

“But you see? It worked, didn’t it? With Gene Hibbs doing my makeup and Peggy Shannon my hair, I really saved the producer money, because I am always ready. And I don't like to take too much credit, because Jay Sommers and Dick Chevillat write marvelous scrips, but I established this character when I wore a chiffon negligee to chase a chicken across the barnyard.

The scene just described by Eva was in an early episode at the beginning of the season with Lisa trying to adjust to living on the farm her husband, Oliver (Eddie Albert), had just purchased. Instead of the ordinary robe prescribed originally, Eva persuaded the director that if Lisa ever chased chickens at all, it would be in a Jean Louis negligee.

“I know this character,” Eva maintains, "because she is like me. When Lisa wears jeans, I make sure they have diamonds for me to wear with them, and I mean real diamonds. If I know they are real diamonds, then the viewers believe it, too.”

STRIVE FOR QUALITY

When Eva digs in adamantly for such conditions, she does not consider it temperament but a striving for a standard of quality that will benefit everyone concerned. She knew she was running the risk of blowing the whole deal by insisting on Jean Louis gowns, diamonds, etc., and Eva wanted this break of co-starring in her own series. “But, darling,” as she says, “what is a break, if it is not done right?”

And, of course, she is right. In one “Green Acres” episode the past season Eva wore a Jean Louis she had worn few weeks earlier. Within two days she had letters from fans demanding to know, “What happened? Can’t you afford a new dress?”

The only temporary setback Eva encountered in her battle for quality was over a proper dressing room. Her first one was a portable job which even the chickens in “Green Acres” might have declined to roost in.

HAS EVERYTHING

“Ah, but after the first Nielsen rating came in, you should see my dressing room. It has everything! But why not? This lunch you and I are having is the first time I've been out of my house or the studio since June. I don’t go to parties. I have to train like an athlete. But I don’t mind. I adore acting. That is why I am 10 minutes early on the set every morning. Also, what these Hollywood people don't realize, I come from the stage and I have discipline.

“I believe there is such a thing as ‘the show must go on.’ Just yesterday I get word that Jolie, my mother, has fallen getting out of her swimming pool and broken her kneecap in three places, a horrible thing. And on the same day my little dog has a stroke, so I am very worried, but I am on the set working anyway.”

MORALE RISES

Eva’s morale has risen since her husband left his stockbroker's job in New York and moved to Hollywood (he waited for the third Nielsen rating on “Green Acres”). Soon after arriving, he became a vice-president for Filmways, the corporation that produces “Green Acres.”

Only two things have not worked out for Eva according to plan. She dare not wear in private life any of the 160 Jean Louis dresses accumulated from the show, because everyone has already seem them on TV. Second, the hillbilly slang on “Green Acres” is spoiling her not-too-recent mastering of the American idiom. When someone on the set mentioned sex the other day, Eva said, “Don’t kick it.” It took a few seconds for the assembled group to figure out she meant “Don't knock it.”

The second season carried on bizarreness (Lisa’s hen lays square eggs) and sly satire (Arnold the Pig gets a draft notice) and continued to get renewed until 1971 when CBS wiped the show off the schedule after 170 episodes.

Tuesday, 14 March 2023

Toby's Dressed Up

The Milkman is a cartoon with three not-all-together acts. The first part of the short features Toby the Pup delivering milk with his horse and wagon with a series of gags, bottles landing here and there, and the horse deciding to go to sleep.

Next, Toby abandons his horse in a little car conveniently in his wagon, and runs into a storm, with rainfall jokes taking up footage.

Our hero (and a small tree) take up refuge in a house which, somehow, has a huge dance hall, and we get musical jokes to finish off the short.

The Toby shorts, and there were 12 of them made by the Winkler (Charles Mintz) studio for release by RKO, are kind of Fleischer Light. Considering Dick Huemer was involved in them, that’s not much of a surprise, but they don’t have as many unexpected throw-away gags as you’d find in a Bimbo Talkartoon short.

The Milkman does have some enjoyable bits. After the horse blows a steam whistle, Toby throws away his bottles.

He reaches into a hidden pocket to put gloves over his gloves.

Next, he reaches behind himself to pull out some spats, which he wears after putting them on over his head.

Now he pulls something out of his belly button. At first, it looks like a cane, but it’s actually a top hat.

Hidden under his, uh, fur, is a cigar and a cleaver, which he uses to chop off the end of his cigar.

Why Toby decides to put on formal wear isn’t apparent, at least to me.

Harrison’s Reports of the day listed the release date as February 20, 1931 while the Motion Picture Herald gave February 25. Despite that, The Film Daily of July 21, 1930 reported “Animation for ‘The Milkman,’ third of the ‘Toby, the Pup’ cartoons has been completed, according to the report from Mintz. It is now in the recording room.” There is a York Daily News-Times ad for the cartoon on the bill at the York Theatre on October 12, 1930. Toby lasted one season. RKO already owned Van Beuren Productions, which made Aesop’s Fables, and replaced Toby with in-house animated shorts starring the human Tom and Jerry.

Next, Toby abandons his horse in a little car conveniently in his wagon, and runs into a storm, with rainfall jokes taking up footage.

Our hero (and a small tree) take up refuge in a house which, somehow, has a huge dance hall, and we get musical jokes to finish off the short.

The Toby shorts, and there were 12 of them made by the Winkler (Charles Mintz) studio for release by RKO, are kind of Fleischer Light. Considering Dick Huemer was involved in them, that’s not much of a surprise, but they don’t have as many unexpected throw-away gags as you’d find in a Bimbo Talkartoon short.

The Milkman does have some enjoyable bits. After the horse blows a steam whistle, Toby throws away his bottles.

He reaches into a hidden pocket to put gloves over his gloves.

Next, he reaches behind himself to pull out some spats, which he wears after putting them on over his head.

Now he pulls something out of his belly button. At first, it looks like a cane, but it’s actually a top hat.

Hidden under his, uh, fur, is a cigar and a cleaver, which he uses to chop off the end of his cigar.

Why Toby decides to put on formal wear isn’t apparent, at least to me.

Harrison’s Reports of the day listed the release date as February 20, 1931 while the Motion Picture Herald gave February 25. Despite that, The Film Daily of July 21, 1930 reported “Animation for ‘The Milkman,’ third of the ‘Toby, the Pup’ cartoons has been completed, according to the report from Mintz. It is now in the recording room.” There is a York Daily News-Times ad for the cartoon on the bill at the York Theatre on October 12, 1930. Toby lasted one season. RKO already owned Van Beuren Productions, which made Aesop’s Fables, and replaced Toby with in-house animated shorts starring the human Tom and Jerry.

Labels:

Toby the Pup

Monday, 13 March 2023

He's My Hero

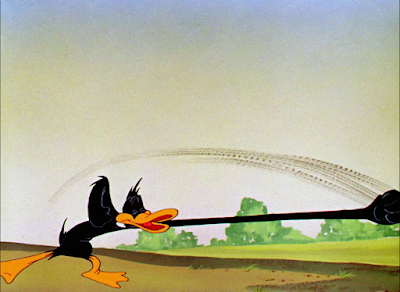

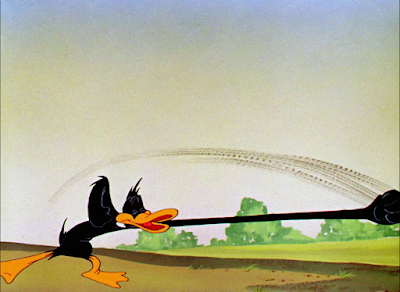

Daffy Duck is ecstatic Dick Tracy (in his comic book) has nabbed the criminals. There’s a fun scene where Daffy leaps around for joy. Here are some frames.

“Oh, boy! If I could only be Dick Tracy, I’d show those gooney criminals,” says Daffy, swinging his fist to punch out some crooks. He punches himself into dreamland instead.

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is full of the kind of energy you’d find in Bob Clampett’s shorts for Warners. It was the last he completed for the studio. He began work on Bacall to Arms, but left and it was finished by Art Davis. Neon Noodle and the rest of the Chester Gould-esque villains were released to theatres, according to Boxoffice magazine, on July 27, 1946. The cartoon didn’t appear at the Strand (a Warners theatre) in New York until the end of August, but was screened at the Strand (a Warners theatre) in Altoona, Pa. on its release date.

Manny Gould, Rod Scribner, Izzy Ellis and Bill Melendez were the credited animators.

“Oh, boy! If I could only be Dick Tracy, I’d show those gooney criminals,” says Daffy, swinging his fist to punch out some crooks. He punches himself into dreamland instead.

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is full of the kind of energy you’d find in Bob Clampett’s shorts for Warners. It was the last he completed for the studio. He began work on Bacall to Arms, but left and it was finished by Art Davis. Neon Noodle and the rest of the Chester Gould-esque villains were released to theatres, according to Boxoffice magazine, on July 27, 1946. The cartoon didn’t appear at the Strand (a Warners theatre) in New York until the end of August, but was screened at the Strand (a Warners theatre) in Altoona, Pa. on its release date.

Manny Gould, Rod Scribner, Izzy Ellis and Bill Melendez were the credited animators.

Labels:

Bob Clampett,

Warner Bros.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)