Howard Beckerman is not only a veteran of the Golden Age of animated cartoons and a respected instructor, but he’s an author, too. We’re not just talking about

his book at his web site. Howard wrote a column for

Back Stage, a New York-based periodical.

We posted

this great remembrance by Mr. Beckerman about Jim Tyer. The article below won’t mean as much to some fans, I suspect. He goes on a little tour of part of Manhattan, and talks about the commercial production studios that briefly flourished during that great period when black-and-white TV sets were filled with cleverly-designed animated commercials. While there were many small studios on the West Coast then, there were a handful based in New York. They deserve a bit of attention by cartoon fans, hence I pass it along.

This was published August 6, 1982. New Yorkers may appreciate this post more than others as they’ll know the streets named.

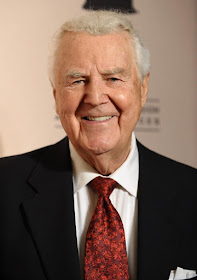

Mr. Beckerman has a nice, friendly style of writing. He is still around and will turn 90 next year.

Errands

It is summer, and contrary to many other summers, animation assignments have been coming to many of the studios on a hit and miss basis. Time was when summer meant beefed up schedules to meet fall deadlines and the rush to produce pre-Christmas announcements. With everyone apparently holding back this season, the small studio operator finds he’s got some extra moments on his hands. He or she can use the time to make additional calls to usual work sources or prepare some artwork for an ad to be placed in a trade journal. Back Stage for instance is receiving material its special animation issue scheduled for September 10th.

When things are a bit slow I find that it’s a good time to do errands. It gets me onto the street for some needed exercise and I get to meet some of the people that I only get to know through the less personal method of telephone calls. This morning for instance I decided to retrieve a negative from Movielab. While the many messenger services in the city are capable and dependable there’s nothing like doing it yourself and perhaps knocking off a few more errands on the way. It’s also a good way to get some bills paid in person and save a few cents on the high cost of stamps. I left my studio on 45th Street, but first stopped into:

A.I. Friedman’s art store to pay a bill and say hello to George, the manager. Then I headed over toward the Avenue of the Americas, more properly known as Sixth Avenue. As I passed 49 West 45th Street I recall that it was here that such studios as Bill Sturm Productions and Academy Pictures had once occupied the same office space at different times, and both had gone out of business in that same space.

I began to ponder how many animation studios had come and gone in the little buildings along this street and are now moved on and the buildings replaced by high rise shiny glass and metal behemouths [sic]. At 165 West 46th Street, former home of Back Stage, the studio, Animation Central once operated with such talents as Paul Kim and Lou Gifford, Pablo Ferro and Ray Favata. As I headed toward Seventh Avenue I spotted a dime on the street and picking it up I realized that one of the other benefits of doing errands, you find money. When you go home and your spouse asks if the agency sent the $10,000 check you can answer, “No but I found a dime.” It’s actually very gratifying when you realize that the 10 grand gets paid out to employees, landlords, services and taxes but the dime is all yours!

Heading past 723 Seventh Avenue I realized that this was another address for the old Bill Sturm animation studio where partners, Bill Sturm, Orestes Calpini and Bert Hecht made some of the earliest television commercials. A couple of blocks north at 49th Street the Embassy 49 is showing Disney’s “Bambi.” It struck me that this theatre had not too long ago been an X-rated movie house and here they were all nice and tidy showing Disney G-rated films. This was the same theatre that was called The World and back in the late 40’s exhibited Roberto Rosselini’s “Open City” for a year, featuring the writing skills of a former cartoonist, Federico Fellini.

At 51st and Seventh I took a moment to drop in to TR’s Gallery, which offers for sale original cels from Disney films. Here for about $175 you can get a hand inked colored cel of Winnie the Pooh or characters from “Jungle Book” or “The Rescuers.” Turning the corner and moving onto 53rd and Broadway I passed the Broadway Theater and was reminded by a plaque in the lobby that this was once the Colony Movie Theater and in September of 1928 Mickey Mouse premiered on the screen in an early synchronized sound cartoon, “Steamboat Willie.” The plaque dutifully includes the engraved likeness of Mickey for the perusal of all those arriving the [to] see the current musical production, “Evita.”

I headed down through 55th Street past the DuArt building and recalled that in the early 50’s Lee Blair’s Film Graphics was situation here and we did many spots for many of the prominent shows of the day. “I Love Lucy” was one of the hits of home television and animation director Don Towsley kept us all struggling on the openings for this series. DuArt’s administrative offices today are where Deborah Kerr once performed for a public service spot. Upstairs was a studio called Loucks and Norling which specialized in technical animation for scientific films. Continuing on top Movielab over in Potamkin Country I passed by 450 West 54th Street where you can just barely make out the faded logo of Fox’s Movietone News. On this street ABC has a sound stage and I recall that not too far away Robert Lawrence had a live action stage and an animation studio across the street in the early 1960’s.

Eventually I arrived at Movielab and picked up the material that was waiting there for me. When I started back to my office the late morning heat was beginning to settle in. I arrived once more at 45th Street about an hour from when I had begun my errand and I realized that it was here on this same street that I had also begun my career in this field working at Famous Studios at 25 West 45th Street. Here at the studio that had once belonged to Max and Dave Fleischer we produced Popeye and Casper the Ghost theatrical shorts. Next door at 34 West there had been the animation studio of Ted Eshbaugh just before the Transfilm organization took over the same building. Today the buildings, 25, 35 and 45 West 45th Street still house several studios, among them, The Optical House, John Rowohlt Camera Service and Eighth Frame Camera Service. Suddenly I realized that I had gone in a complete circle, not just from my office to the lab and back, but as it happens to everyone, I had gone on another errand between the past and the present and back again. Though the term errand boy is often used disparagingly, it must be remembered that the very nature of the film business requires that everyone become an errand boy at sometime. There is hardly a producer no matter how high in status who has never carried a reel to an editor, a lab, an optical house or a screening. Sometimes it’s the only way to get it there. We are all candidates for the errand boy’s job, and like any conscientious errand boy, we do our job with care and responsibility, we are professionals. The call comes and we pick up and deliver. The agency picks up and delivers for the client, and we pick up and deliver for the agency.

We speak of art and technique, of style and moody, but what it comes down to is, can you pick up and deliver?

As I entered the welcoming air conditioned confines of my studio and even before the small beads of perspiration had dried on my forehead, the phone rang. It was an assignment. Pick up and deliver.