The interaction between Groucho Marx and the contestants on “You Bet Your Life” made the show unique and that’s probably why it was never really successfully cloned or revived. Some contestants were feisty and unintentionally funny. Others were nervous and unintentionally funny. And yet others were completely oblivious to Groucho’s putdowns and were unintentionally funny.

People who appear on game shows are part of our lives for a fleeting moment, usually a day or two (unless their name is Ken Jennings), then vanish as they’re replaced by someone else. Few of us every wonder “Whatever happened to so-and-so who was on such-and-such show last month?” Well, someone at the Radio and TV Mirror did. They found there was a neat little story about a couple who took the stage opposite Groucho on “Your Bet Your Life.” It was perfect for the housewives reading the magazine. It featured an ideal Mr. and Mrs. Young Suburban America of the 1950s, some amusing anecdotes and a happy ending.

The story appeared in the May 1952 issue, told from the point of view of the housewife-contestant (who perhaps received editorial assistance in crafting her story). You may zone out once she gets to the travelogue part but the first two-thirds of the story are an interesting account of what it was like being on the show.

YOU BET YOUR LIFE!

By NADINE SNODGRASS

It was a minor miracle, that's what it was. When we talk about it now, we still shake our heads and wonder whether we dreamed it all. Then we look over our gifts, our photographs, and we read some of the letters we received, and we are forced to admit that anything can happen when — you bet your life.

To start at the beginning and be sensible about it — which isn't easy — Tom and I are what I believe you would describe as the usual young American couple. We have been married a little over a year. We live in a modest, unfurnished apartment in Inglewood, California (a suburb of Los Angeles proper); we are buying our furniture, some of it on the installment plan, and we are expecting a baby any minute now. Tom is an electronic technician at Hughes Aircraft Corporation. I had held my secretarial job until we discovered that we were going to have a family. That's how average we are.

One night a young couple who live in our neighborhood telephoned to say that they had four tickets to the Groucho Marx television show, You Bet Your Life. Would we like to join them? It seemed like a fine idea.

I put on my favorite maternity outfit; a green gabardine skirt and a plaid taffeta smock. Tom slicked down his hair and we were ready. On our way to the station, the four of us kidded a little about appearing on a quiz show and winning the jackpot. We agreed that we would enjoy a television set of our own, or a trip to Europe, or a furnished bungalow into which we could move.

Tom said, "You married the wrong man, honey, for a break like that. I've never won anything in my life."

I said that I felt I had had all the luck a girl deserves when I met and married him. You know how wonderful it is when you're happily married and planning a great life together.

Actually it didn't occur to us that we'd have a chance to appear on the show. We assumed, as I suppose most people do, that the program was well set in advance. That's why Tom and I raised our eyebrows at one another when the show announcer, George Fenneman, asked for young couples in the audience to volunteer to play You Bet Your Life.

Tom leaned over and whispered to me, "Would you be game?"

"Why not?" I answered. "We have nothing to lose and I think it would be fun. Maybe we're smarter than we think!" (Tom is still kidding me about that.)

There were several of us who were ushered into various dressing rooms off the corridor from the main studio and there, couple by couple, we were interviewed. Tom and I still can't figure out how we happened to be chosen. Tom says it was because it was obvious that I was a "prominent" citizen!

We shook hands for luck and I noticed that Tom's hands were almost as cold as mine. "Scared?" he asked.

I started to say that I wasn't, but my throat was so dry that I couldn't speak for a second. When I could get my voice to function, I sort of squeaked, "Petrified." "Nothing to it," Tom said, putting his arm around me. "We're just going to talk to Groucho Marx. That'll be fun."

As we were the third couple to come before Mr. Marx that evening, we had final choice of the categories suggested. We chose famous resort spots, thinking of Lake Placid, Atlantic City, Miami, Colorado Springs, Palm Springs, Sun Valley, Honolulu, and even of Cannes and Biarritz. Mr. Marx rolled his eyes and waved his famous cigar in our direction after we had been introduced, and asked, "Which are you hoping for, a boy or a girl?"

I said that this baby was our first, so we didn't care.

"If it's a boy," Mr. Marx said, goggling from us to the audience, "name him after me. Imagine going through life with the name of Groucho Snodgrass!"

Tom and I nearly collapsed, laughing. Around the house we still refer to the anticipated as "Groucho!"

"In what state is Lake Placid?"

Tom grinned. He had thought of that resort when we first decided on the category. "New York," answered Tom.

"In what state is Sarasota?"

Tom and I looked at one another with wide eyes. I hadn't an idea in the world. I knew I had heard the word, but where? We whispered. I said I thought it sounded . like an Indian name. Time was running out, so we decided to say "Michigan."

"Sorry. Sarasota is in Florida. It is the winter headquarters of Ringling Brothers-Barnum and Bailey Circus. Too bad, kids," Mr. Marx said. It was obvious that he meant it. "I don't want you to go away broke, so for ten dollars can you tell me who wrote Brahms' 'Lullaby'?"

We weren't too flustered to know that one. The audience had uttered a groan when we didn't know where Sarasota was, but they gave us a nice hand when we won our ten dollars.

Oh well, we said on the way home, it had been a terrific experience and we had come home ten dollars richer than when we left— which was something exceptional in these days. During the next few days a number of amazing things happened. I received a jubilant letter from my mother in Chicago. We hadn't seen each other for four years and Mother had never met Tom, but she had caught that particular Groucho Marx show. You can imagine how thrilled she was.

We were just settling down to normal again when a representative of You Bet Your Life telephoned and asked what reaction Tom and I had experienced from being on TV. I told him some of our happenings and he said, "We want you to come back again. We have a surprise for you."

I wrote Mother to warn her to be watching, and we went back to the broadcasting studio the following Thursday. This time we weren't particularly nervous and Tom said that if they gave us another chance he was going to pick the same category again. He had been studying maps!

Groucho kidded a bit, as he usually does, then he said to Tom, "I wonder if you can tell me where . . ."

"Sarasota is in Florida," interrupted Tom.

"You bet your life," answered Groucho, and pulled a letter from his pocket. "Listen to this," he said.

The letter had been written by Mr. Tod Swalm, general manager of Sarasota (Florida) Chamber of Commerce. Mr. Swalm was aghast to think that anyone in the world was ignorant of the whereabouts of his city. He and Sarasota were, therefore, inviting Tom and me to enjoy a week's vacation in Sarasota as guests of the resort from the time we left Los Angeles by air until we again returned to Los Angeles International Airport.

We simply shrieked with delight, and so did everyone in that TV audience. It was a great night for Sarasota, and a greater one for the Snodgrasses.

Behind the scenes, afterward, Tom and I realized that there were some problems to be solved. Tom would have to ask for the time off, of course, and I would have to consult our doctor.

Even before Tom had left for the office the next morning, Mr. Nate Tufts, a representative of You Bet Your Life, was on the telephone, asking eagerly, "Can you go?"

I wanted to ask him who was more excited, the staff of You Bet Your Life or the Snodgrasses, but I didn't. I simply explained that it wasn't yet nine o'clock. Tom hadn't called me yet about his time off and I hadn't seen the doctor, but I can't tell you how pleased I was to have the entire staff of You Bet Your Life show such interest in us.

From that instant on, everything went along as if a fairy godmother had touched us with a magic wand. Tom's boss was as interested in our trip as the rest of our friends were. The doctor said I was getting along fine and that the experience would be priceless. Tom's mother said, when I told her that we were going to be sensible and buy no extra clothes for the trip, "You should have a suit in which to travel. Something new adds to a trip. Come on, let's go shopping."

We left Los Angeles at midnight on Monday, January 14. Tom had flown many times, but it was my first airplane trip. Everyone had said I would be able to relax and sleep, but who can sleep with one's heart going bumpety-bump, ninety miles a minute? I pressed my nose against the window and looked at the moon and then at the little , towns, twinkling like a nest of fireflies far, far below. I watched the night grow light, and the sunrise, too. I slept a little during the morning, and then we landed at Tampa at two o'clock in the afternoon.

Mr. Swalm of the Sarasota Chamber of Commerce and representatives of the Campbell-Davis Motors of Sarasota met us in a new De Soto. Also there were several photographers who snapped pictures as if we had been celebrities. This flashbulb life bothered me at first, but after two days of it, Tom and I became veterans. We are to receive an album including every shot taken so that someday we will be able to tell this story to our grandchildren, complete with illustrations.

From the airport we were whisked over a beautiful fifty-mile drive to Sarasota. Our first impression of the city was that it was something like Laguna Beach, a charming resort city in Southern California. It had the same beautiful vistas of the sea, the same vacation atmosphere, the same alluring shops, but Sarasota was (whisper it) warmer.

Our first big thrill was the reception given in our honor. This was attended by the mayor and all city dignitaries, and we were given a key to the city. Also, Tom received a bright shirt and swim trunks as well as a camera and twelve rolls of film. I was given a handsome green leather shoulder bag, and a pretty full-circle peasant skirt. We were also given a set of Skyway luggage. The baby did very well, too: it was given a pink crib blanket, an air mattress, a set of fitted sheets, a comb and brush set.

Our "home" in Sarasota was the Coquina, an apartment-hotel which is the last word in luxury. We had an apartment with a compact kitchen, a living room looking out upon a beach whose sand is like face powder, and a beautiful bedroom. The refrigerator in our kitchen was stocked daily with cream, milk, ham, eggs, and wonderful bakery goods so that we could have breakfast whenever we awakened.

A luncheon was planned for us every noon, and dinner was planned for us every night. We visited almost every famous restaurant and night club in Sarasota. And how we danced on the moonlit terraces overlooking the ocean! It was twenty-four-hour paradise plus a second honeymoon.

Now that we are back in our apartment in Inglewood we remember the most wonderful week any two people could experience. I'm still misty-eyed about it and a good deal of my spare time has been spent reliving the days and recapturing the breathless feeling of being young, in love, and on a magic holiday.

The amazing thing to us is that making a mistake on a radio program could bring such a trip to two ordinary people. It proves that no one should ever give up hope of being touched by Lady Luck's sparkling wand. It happened to us. It could happen to you!

The Snodgrasses would have appeared on a fair number of TV sets that season. “You Bet Your Life” finished tenth in the ratings in 1951-52 with a 42.1 share, opposite “Stop the Music” on ABC and Burns and Allen and “Star of the Family” (with Peter Lind Hayes and Mary Healy) alternating on CBS. Groucho was still doing the show on radio, too, on Wednesday nights at 9 against Red Skelton on CBS, “Rogue’s Gallery” on ABC and “The Hidden Truth” on Mutual.

Something which is interesting is revealed in the photo of the Snodgrasses which accompanied the article. Nadine is visibly pregnant. Pregnancy was a touchy subject, at least when it came to sitcoms, and she may have been one of the first almost-moms to have appeared on network TV.

Thomas Louis Snodgrass and Nadine Willie Hickman were married August 18, 1950 in Los Angeles. Where are the Snodgrasses today? I haven’t been able to find out. If you’re reading, Tom or Nadine, drop me a note. But we can tell you they had a boy named Timothy Allen, 7 pounds 5 ounces. Sorry, Groucho.

Wednesday, 10 September 2014

Tuesday, 9 September 2014

White With Fright

Sylvester opens the fence door into Granny’s yard, not realising it’s full of large, cat-hating bulldogs in “Ain’t She Tweet.” After a stationary shot of the fence while dogs bark on the soundtrack, Sylvester rushes out and closes the door.

I’ve always liked the doggie dentures that are still clamped on Sylvester’s tail.

Friz Freleng’s animators on this one are Manny Perez, Virgil Ross, Ken Champin and Art Davis.

I’ve always liked the doggie dentures that are still clamped on Sylvester’s tail.

Friz Freleng’s animators on this one are Manny Perez, Virgil Ross, Ken Champin and Art Davis.

Labels:

Friz Freleng,

Warner Bros.

Monday, 8 September 2014

Hmmm...It's a Possibility

It would seem appropriate that Adolf Hitler’s personal Hell would be an eternal land populated by Jews. I doubt Tex Avery was going for anything that weighty or symbolic in his MGM cartoon, “Blitz Wolf.” He was merely using a catchphrase from Kitzel on “The Al Pearce Show” in the cartoon’s final scene where Adolf Wolf is blown to you-know-where.

This scene is the work of the great Preston Blair. Irv Spence, Ray Abrams and Ed Love were the other animators in the first Avery cartoon released by Metro in 1942.

This scene is the work of the great Preston Blair. Irv Spence, Ray Abrams and Ed Love were the other animators in the first Avery cartoon released by Metro in 1942.

Sunday, 7 September 2014

Did He Have the Melon?

Jack Benny’s publicist must have had a thing about bathrobes.

I’ve found several different 1960s print interviews arranged with Jack in his hotel room as he seemingly just got out of bed. In each case, the reporter remarks on it in the story. I don’t know how many stars today would tolerate before-noon, in-suite interviews, but Jack did.

This Associated Press column is from November 27, 1966. Its purpose is to plug a TV show. It contains no surprises if you’ve read other newspaper feature stories from the ‘60s. But newspaper readers then didn’t have the luxury of going on-line and digging up a bunch of interviews conducted over several decades so it was probably news to them.

The photo on this post accompanied the column.

Jack Benny, 39 Going on 73, To Needle Beauty Pageants

EDITOR'S NOTE: Jack Benny, nearing 73, is one of the busiest senior citizens in show business. And that's the way he likes it, playing "straight man for the whole world." And if his Thursday night special puts him on top of the Nielsens, that wouldn't make him unhappy.

By CYNTHIA LOWRY

Associated Press Writer

New York — Jack Benny opened the door of his hotel suite, then quickly retreated into another room and reappeared in dressing gown.

"Forgive me, forgive me," he apologized. "It's this time difference from California."

His manager, Irving Fein, who accompanies him on all professional journeys, appeared from an adjoining room, and everybody sat down to breakfast.

Benny, whose manner and mien belie his year, eyed two glasses of orange juice and one slice of Persian melon.

"Who gets the melon?" he demanded, in that petulant, ready-to-get-my-feeling-hurt voice he has developed over 35 years of radio and television. Then he laughed, and said he'd rather have orange juice anyway.

Benny, in spite of the fact that his official biography states that he was "born 39 years ago in Chicago, will be 73 in February. And, although in semi-retirement from television for two seasons, he manages to be about the busiest senior citizen in show business.

A professional errand of mercy jetted him to New York this time—to be a guest star on CBS Garry Moore Show, part of a desperate, effort to save the show from sagging ratings.

• • •

BENNY had just finished making his annual special, and was also using his time to plug it. A spoof on beauty pageants and loaded with former contest winners, it will be broadcast next Thursday on NBC. Benny is not the funniest man in the world off-camera. In fact, he is a bland, somewhat understated fellow who is rated by his colleagues as the greatest audience for humor in the world.

Steve Allen, in his book "The Funny Men," says that Benny is "to humor what Artur Rubinstein is to music: "A performer of genius." He calls Benny the world's greatest "reactor" to jokes and situations, which usually are on him—"straight man for the whole world."

Over years of show business Benny has honed his professional character: A conceited tightwad of easily punctured dignity. And years of limelight have also developed what is widely believed to be his "real" character—a generous, outgoing and modest man who is an inordinately big tipper and a lavish appreciator of other people's humor.

• • •

IN AN INTERVIEW, Benny will have pleasant words about all his colleagues. He will discuss his recent move from his Beverly Hills home to an apartment close to his favorite golf course. He speaks of enjoying freedom to spend more time in his Palm Springs home — although he has not done so yet—and the pleasures of doing charity concerts all over the country with top orchestras.

Benny practices on his violin at least two hours a day. He's a much better violinist than he appears to be; it takes considerable skill to play delicately off-key. He goes to his office daily. He performs on a lot of stages.

"It is a good life," he says. "I enjoy playing a few weeks a year in Nevada—once I get accustomed to the turnaround in hours. And I like to be able to work on a concert or a show for a few concentrated weeks and then take time off." Over the years, Benny shows have been real innovators. The old radio show and the newest special, however, are built from the same brick and mortar. There will be the "stingy" jokes and several samples of his fantastic timing.

• • •

BENNY'S FIRST radio broadcast was a 1932 Ed Sullivan Show, and his opening lines were:—“This is Jack Benny. There will be a slight pause while every one says, ‘Who cares?’” Today, Benny can produce laughter merely by exploding “cut that out” or just by facing the audience thoughtfully and droning "Hmmmmm." Over 35 years, the audience has come to know the character and is conditioned to laugh.

Benny's timing is peerless. Don Wilson once told a magazine writer that when Benny turns to the audience for his famed long "reaction," other actors are not allowed to continue with their lines. The signal to resume comes when he again faces his fellow performers.

Benny jumped off the Sullivan Show into his own NBC series in 1932 and was one of the network's big stars until the famous "Paley's Raid" of 1949 when CBS wooed away big names like Benny, Bergen and Skelton. He continued the radio show until 1955, but in 1950 started his television series. These continued, in one form or another on CBS until 1964, after which he returned to NBC for one season of specials.

When the weekly show was discontinued for low ratings, Benny was not exactly happy, but obviously he has adjusted to the idea of one special a year, plus as many guest shots as he wants to take on.

"Listen," he confided, in mock exasperation. "I am an awfully easy fella to get along with. I like everything I do and I'm happy with everything I do. I like to work and I like to practice. I even like to walk down Fifth Avenue and have people say hello to me."

And, for his amour-proper, he'd also like it very much if his Jack Benny Hour Thursday landed him on top of the Nielsen ratings.

Oh, yes, and he did, after all, eat the melon.

I’ve found several different 1960s print interviews arranged with Jack in his hotel room as he seemingly just got out of bed. In each case, the reporter remarks on it in the story. I don’t know how many stars today would tolerate before-noon, in-suite interviews, but Jack did.

This Associated Press column is from November 27, 1966. Its purpose is to plug a TV show. It contains no surprises if you’ve read other newspaper feature stories from the ‘60s. But newspaper readers then didn’t have the luxury of going on-line and digging up a bunch of interviews conducted over several decades so it was probably news to them.

The photo on this post accompanied the column.

Jack Benny, 39 Going on 73, To Needle Beauty Pageants

EDITOR'S NOTE: Jack Benny, nearing 73, is one of the busiest senior citizens in show business. And that's the way he likes it, playing "straight man for the whole world." And if his Thursday night special puts him on top of the Nielsens, that wouldn't make him unhappy.

By CYNTHIA LOWRY

Associated Press Writer

New York — Jack Benny opened the door of his hotel suite, then quickly retreated into another room and reappeared in dressing gown.

"Forgive me, forgive me," he apologized. "It's this time difference from California."

His manager, Irving Fein, who accompanies him on all professional journeys, appeared from an adjoining room, and everybody sat down to breakfast.

Benny, whose manner and mien belie his year, eyed two glasses of orange juice and one slice of Persian melon.

"Who gets the melon?" he demanded, in that petulant, ready-to-get-my-feeling-hurt voice he has developed over 35 years of radio and television. Then he laughed, and said he'd rather have orange juice anyway.

Benny, in spite of the fact that his official biography states that he was "born 39 years ago in Chicago, will be 73 in February. And, although in semi-retirement from television for two seasons, he manages to be about the busiest senior citizen in show business.

A professional errand of mercy jetted him to New York this time—to be a guest star on CBS Garry Moore Show, part of a desperate, effort to save the show from sagging ratings.

• • •

BENNY had just finished making his annual special, and was also using his time to plug it. A spoof on beauty pageants and loaded with former contest winners, it will be broadcast next Thursday on NBC. Benny is not the funniest man in the world off-camera. In fact, he is a bland, somewhat understated fellow who is rated by his colleagues as the greatest audience for humor in the world.

Steve Allen, in his book "The Funny Men," says that Benny is "to humor what Artur Rubinstein is to music: "A performer of genius." He calls Benny the world's greatest "reactor" to jokes and situations, which usually are on him—"straight man for the whole world."

Over years of show business Benny has honed his professional character: A conceited tightwad of easily punctured dignity. And years of limelight have also developed what is widely believed to be his "real" character—a generous, outgoing and modest man who is an inordinately big tipper and a lavish appreciator of other people's humor.

• • •

IN AN INTERVIEW, Benny will have pleasant words about all his colleagues. He will discuss his recent move from his Beverly Hills home to an apartment close to his favorite golf course. He speaks of enjoying freedom to spend more time in his Palm Springs home — although he has not done so yet—and the pleasures of doing charity concerts all over the country with top orchestras.

Benny practices on his violin at least two hours a day. He's a much better violinist than he appears to be; it takes considerable skill to play delicately off-key. He goes to his office daily. He performs on a lot of stages.

"It is a good life," he says. "I enjoy playing a few weeks a year in Nevada—once I get accustomed to the turnaround in hours. And I like to be able to work on a concert or a show for a few concentrated weeks and then take time off." Over the years, Benny shows have been real innovators. The old radio show and the newest special, however, are built from the same brick and mortar. There will be the "stingy" jokes and several samples of his fantastic timing.

• • •

BENNY'S FIRST radio broadcast was a 1932 Ed Sullivan Show, and his opening lines were:—“This is Jack Benny. There will be a slight pause while every one says, ‘Who cares?’” Today, Benny can produce laughter merely by exploding “cut that out” or just by facing the audience thoughtfully and droning "Hmmmmm." Over 35 years, the audience has come to know the character and is conditioned to laugh.

Benny's timing is peerless. Don Wilson once told a magazine writer that when Benny turns to the audience for his famed long "reaction," other actors are not allowed to continue with their lines. The signal to resume comes when he again faces his fellow performers.

Benny jumped off the Sullivan Show into his own NBC series in 1932 and was one of the network's big stars until the famous "Paley's Raid" of 1949 when CBS wooed away big names like Benny, Bergen and Skelton. He continued the radio show until 1955, but in 1950 started his television series. These continued, in one form or another on CBS until 1964, after which he returned to NBC for one season of specials.

When the weekly show was discontinued for low ratings, Benny was not exactly happy, but obviously he has adjusted to the idea of one special a year, plus as many guest shots as he wants to take on.

"Listen," he confided, in mock exasperation. "I am an awfully easy fella to get along with. I like everything I do and I'm happy with everything I do. I like to work and I like to practice. I even like to walk down Fifth Avenue and have people say hello to me."

And, for his amour-proper, he'd also like it very much if his Jack Benny Hour Thursday landed him on top of the Nielsen ratings.

Oh, yes, and he did, after all, eat the melon.

Labels:

Cynthia Lowry,

Jack Benny

Saturday, 6 September 2014

The Shutdown

The average person going to the movies in 1953 would never have known it. Bugs Bunny was still on the big screen; by the end of September, he was even in 3-D. But the people who drew Bugs would have known it because they weren’t working.

Warner Bros. had shut down almost its entire cartoon studio.

The shutdown didn’t last long, 5 1/2 months for two of the animation units, longer for the third. And you can put part of the blame on 3-D.

Daily Variety reported on April 29, 1953 that “Warner Bros, is now in a state of suspended animation, while studio execs study public reaction to ‘House of Wax.’” The Vincent Price thriller was made in 3-D, one of a number of ideas tried by studios to get people away from their TV sets and into movie houses again. But 3-D was iffy. The Variety story pointed out theatre owners were hesitant to spend the $1,000 needed to retool their houses to show movies in that format. The “suspended animation” ironically applied to the Robert McKimson unit at the Warners cartoon studio. It had been disbanded earlier in the month.

Did anyone see the shutdown coming? Weekly Variety of June 3rd talked of possible expansion: “Warners cartoon studio, ahead of its 20-per-year schedule, is considering an expansion of activities to include a program of commercials.” But writer Mike Maltese saw the proverbial writing on the wall. He must have started poking around for work because he landed a job just as he was being laid off at Warners.

Michael Barrier’s Hollywood Cartoons refers to a story in the June 16, 1953 edition of Daily Variety detailing what happened. It was repeated almost verbatim in the Weekly Variety out of New York the following day. Here’s the story in full. It discusses the situation at other West Coast studios as well.

WB CARTOON STUDIO TO CLOSE DOWN

Warners cartoon studio will shutter Friday [June 19, 1953], with the exception of 10 employes working under topper Edward Selzer, and will remain closed until probably Jan. 4, 1954. Approximately 70 cartoonists are affected by sudden move. At the time they were pink-slipped, they were told by Selzer that they might be recalled within 90 days. More likely, however, exec said, studio would remain dark until January, and it was suggested that those given notices take new jobs.

Those remaining include a director, a story man, a layout man, three background men, a cutter and three office staffers. They will handle a small amount of commercial work during the summer, and prep work for resumption of activity, so no time will be lost when workers return.

Sudden cessation of cartoon activity is due to two chief reasons, a heavy backlog which gives Warners finished releases until late in 1954 and uncertainty in what process to make further cartoons, 2-D or 3-D. Company, which now releases 20 cartoons annually, has 38 cartoons ready for release, 20 more three-quarters complete, including all the animation finished, and 12 stories completed and most of the direction completed.

Two units are affected by studio closing, a third having been closed out two months ago. At that time, the annual releasing slate of 30 subjects was cut to 20.

Metro cartoon department also is a casualty of a big backlog and 3-D. Department now is operating with only a single unit, for its Tom and Jerry series, a second shutting down last March 1. Studio currently has an inventory of 32 completed cartoons for its 24-a-year release. Department is expected to be back in full swing in the early fall, however, Fred Quimby, department chief, declared yesterday, with the second unit again functioning. Studio actually is waiting to see whether to continue with 2-D or go all-out in 3-D, he added. All future films, at any rate, will be adapted to wide-screen projection.

Walter Lantz Studio, on the other hand, has increased its annual output from six to 13, for release through UI. Lantz yesterday hired Mike Maltese, story man who swung over from Warners, and two weeks ago took on a pair of top Metro animators, Ray Patterson and Grant Simmons. Studio also has stepped up its commercial cartoon production.

Who were the ten staffers that were kept? The process of elimination answers some of the question. Chuck Jones went to Disney and Mike Maltese was hired by Lantz, so the writer and director were Friz Freleng and Warren Foster. Presumably, Freleng’s layout man, Hawley Pratt, stayed. Who the “three background men” are is up for debate. If Variety reported correctly and animators weren’t included, the answer may be simple. Irv Wyner had been doing Freleng’s backgrounds, Jones used Phil De Guard and McKimson’s former BG artist, Dick Thomas (on one pre-closure short). Presumably, the film cutter was Treg Brown (whether the studio had more than one cutter at the time, I don’t know). Brown didn’t start getting credits on Warners shorts until some time after the shutdown.

How much of a cartoon backlog did Warners have? Thad Komorowski’s extremely helpful web site fills us in. The last McKimson unit cartoon produced before the shutdown was “Too Hop to Handle,” released January 26, 1956. McKimson animated his unit’s last three cartoons, the final two with the help of former assistant animator Keith Darling. The last Jones cartoon was “Guided Muscle,” released December 10, 1955, with his full contingent of animators, but Phil De Guard drawing the layouts and Dick Thomas the backgrounds; Maurice Noble had left the studio for John Sutherland Productions before this.

A couple of other notes about the story: the MGM unit which shut down was Tex Avery’s. Grant Simmons was one of his animators, while Ray Patterson worked in both the Avery and Hanna-Barbera units. Patterson and Simmons seem to have acted as their own little unit at Lantz. They made two cartoons, “Dig That Dog” (released April 12, 1954) and “Broadway Bow Wow’s” (released August 2, 1954). Internet sites have suggested these cartoons were made by the Grantray-Lawrence studio. As Grantray didn’t exist until July 1954 (see Variety, July 21, 1954), these two shorts couldn’t have been made there.

Selzer said it was likely the Warners studio would re-open on January 4, 1954 and that’s exactly what happened. In the meantime, the Jones-directed 3-D cartoon “Lumber Jack-Rabbit” was rushed into release. It was the only 3-D cartoon short made by Warners. It’s unclear when the studio soured on the idea of people being forced to wear red-and-green glasses to watch its movies.

Here’s Daily Variety again, from December 4, 1953.

WB Cartoon Studio Resumes Production Operations Jan. 4

Warners cartoon studio will resume operations Jan. 4, Edward Selzer, who heads unit, reported yesterday. Unit closed down last June, due to a backlog of nearly one year of completed product. Key workers have been trickling back to WB employment during the past several weeks, to prep a schedule of between 25 and 30 cartoons in 1954, with balance to report before Jan. 4.

In preparation of new schedule, Selzer already has arranged for purchase of an all-purpose camera and crane, which will be installed late this month. Larger swivel units for the animation, inking and painting desk also have been ordered. New cartoon sked calls for subjects to be produced for a 1.75 screen, suitable also for standard showing. Selzer tosses annual Warner Club Christmas party at his home Dec. 20.

Chuck Jones was one of those “key workers;” he had left Disney in November. Tedd Pierce returned as well. He had gone to UPA from Warners well before the shutdown and was replaced with Sid Marcus in the McKimson unit. But Pierce wrote for Jones when he returned; He didn’t write for McKimson right away because only two units operated again when the studio resumed full production. McKimson returned a little later. Variety reported on March 9, 1954.

Warners Expanding Its Cartoon Studio Into Three Units

Warners cartoon studio, which resumed production the first of the year with two units, very likely will be expanded to three following arrival later this month of Norman Moray, Warners' shorts sales [boss].

McKimson’s new unit consisted of Darling, Ted Bonnicksen, a former Disney animator who had been in Freleng’s unit at the time of the shutdown, and Russ Dyson, another ex-Disneyite, who died September 25, 1956 at the age of 50. Thomas handled backgrounds.

Maltese rejoined the studio and the Jones unit at the end of August 1954.

As for MGM, Quimby never did bring back a second unit for theatrical cartoons, but he did have Mike Lah work on the animated segment in the Gene Kelly feature “Invitation to the Dance.” Variety

● Reported on May 27, 1953 a cartoon/live action scene was being considered but hadn’t been filmed,

● Ran a story on August 10th saying it would go ahead,

● Blurbed on March 12, 1954 that Quimby had set a finishing date of June 15th for it but

● Announced on June 8th that Kelly couldn’t shoot it until August.

Lah ended up directing a second unit after Quimby retired around the start of 1956. Meanwhile, Tex Avery landed at Walter Lantz (Daily Variety, Dec. 23, 1953), but lasted only eight months and completed four cartoons.

Warners maintained its cartoon studio into the 1960s, merging it with the commercial and industrial films department under David DePatie. When Variety reported on May 31, 1963 that DePatie-Freleng Enterprises had formed, it stated that what was once the cartoon studio was “a recently dissolved WB subsidiary.” The studio did eventually reopen for a few years, but it just wasn’t the same.

Warner Bros. had shut down almost its entire cartoon studio.

The shutdown didn’t last long, 5 1/2 months for two of the animation units, longer for the third. And you can put part of the blame on 3-D.

Daily Variety reported on April 29, 1953 that “Warner Bros, is now in a state of suspended animation, while studio execs study public reaction to ‘House of Wax.’” The Vincent Price thriller was made in 3-D, one of a number of ideas tried by studios to get people away from their TV sets and into movie houses again. But 3-D was iffy. The Variety story pointed out theatre owners were hesitant to spend the $1,000 needed to retool their houses to show movies in that format. The “suspended animation” ironically applied to the Robert McKimson unit at the Warners cartoon studio. It had been disbanded earlier in the month.

Did anyone see the shutdown coming? Weekly Variety of June 3rd talked of possible expansion: “Warners cartoon studio, ahead of its 20-per-year schedule, is considering an expansion of activities to include a program of commercials.” But writer Mike Maltese saw the proverbial writing on the wall. He must have started poking around for work because he landed a job just as he was being laid off at Warners.

Michael Barrier’s Hollywood Cartoons refers to a story in the June 16, 1953 edition of Daily Variety detailing what happened. It was repeated almost verbatim in the Weekly Variety out of New York the following day. Here’s the story in full. It discusses the situation at other West Coast studios as well.

WB CARTOON STUDIO TO CLOSE DOWN

Warners cartoon studio will shutter Friday [June 19, 1953], with the exception of 10 employes working under topper Edward Selzer, and will remain closed until probably Jan. 4, 1954. Approximately 70 cartoonists are affected by sudden move. At the time they were pink-slipped, they were told by Selzer that they might be recalled within 90 days. More likely, however, exec said, studio would remain dark until January, and it was suggested that those given notices take new jobs.

Those remaining include a director, a story man, a layout man, three background men, a cutter and three office staffers. They will handle a small amount of commercial work during the summer, and prep work for resumption of activity, so no time will be lost when workers return.

Sudden cessation of cartoon activity is due to two chief reasons, a heavy backlog which gives Warners finished releases until late in 1954 and uncertainty in what process to make further cartoons, 2-D or 3-D. Company, which now releases 20 cartoons annually, has 38 cartoons ready for release, 20 more three-quarters complete, including all the animation finished, and 12 stories completed and most of the direction completed.

Two units are affected by studio closing, a third having been closed out two months ago. At that time, the annual releasing slate of 30 subjects was cut to 20.

Metro cartoon department also is a casualty of a big backlog and 3-D. Department now is operating with only a single unit, for its Tom and Jerry series, a second shutting down last March 1. Studio currently has an inventory of 32 completed cartoons for its 24-a-year release. Department is expected to be back in full swing in the early fall, however, Fred Quimby, department chief, declared yesterday, with the second unit again functioning. Studio actually is waiting to see whether to continue with 2-D or go all-out in 3-D, he added. All future films, at any rate, will be adapted to wide-screen projection.

Walter Lantz Studio, on the other hand, has increased its annual output from six to 13, for release through UI. Lantz yesterday hired Mike Maltese, story man who swung over from Warners, and two weeks ago took on a pair of top Metro animators, Ray Patterson and Grant Simmons. Studio also has stepped up its commercial cartoon production.

Who were the ten staffers that were kept? The process of elimination answers some of the question. Chuck Jones went to Disney and Mike Maltese was hired by Lantz, so the writer and director were Friz Freleng and Warren Foster. Presumably, Freleng’s layout man, Hawley Pratt, stayed. Who the “three background men” are is up for debate. If Variety reported correctly and animators weren’t included, the answer may be simple. Irv Wyner had been doing Freleng’s backgrounds, Jones used Phil De Guard and McKimson’s former BG artist, Dick Thomas (on one pre-closure short). Presumably, the film cutter was Treg Brown (whether the studio had more than one cutter at the time, I don’t know). Brown didn’t start getting credits on Warners shorts until some time after the shutdown.

How much of a cartoon backlog did Warners have? Thad Komorowski’s extremely helpful web site fills us in. The last McKimson unit cartoon produced before the shutdown was “Too Hop to Handle,” released January 26, 1956. McKimson animated his unit’s last three cartoons, the final two with the help of former assistant animator Keith Darling. The last Jones cartoon was “Guided Muscle,” released December 10, 1955, with his full contingent of animators, but Phil De Guard drawing the layouts and Dick Thomas the backgrounds; Maurice Noble had left the studio for John Sutherland Productions before this.

A couple of other notes about the story: the MGM unit which shut down was Tex Avery’s. Grant Simmons was one of his animators, while Ray Patterson worked in both the Avery and Hanna-Barbera units. Patterson and Simmons seem to have acted as their own little unit at Lantz. They made two cartoons, “Dig That Dog” (released April 12, 1954) and “Broadway Bow Wow’s” (released August 2, 1954). Internet sites have suggested these cartoons were made by the Grantray-Lawrence studio. As Grantray didn’t exist until July 1954 (see Variety, July 21, 1954), these two shorts couldn’t have been made there.

Selzer said it was likely the Warners studio would re-open on January 4, 1954 and that’s exactly what happened. In the meantime, the Jones-directed 3-D cartoon “Lumber Jack-Rabbit” was rushed into release. It was the only 3-D cartoon short made by Warners. It’s unclear when the studio soured on the idea of people being forced to wear red-and-green glasses to watch its movies.

Here’s Daily Variety again, from December 4, 1953.

WB Cartoon Studio Resumes Production Operations Jan. 4

Warners cartoon studio will resume operations Jan. 4, Edward Selzer, who heads unit, reported yesterday. Unit closed down last June, due to a backlog of nearly one year of completed product. Key workers have been trickling back to WB employment during the past several weeks, to prep a schedule of between 25 and 30 cartoons in 1954, with balance to report before Jan. 4.

In preparation of new schedule, Selzer already has arranged for purchase of an all-purpose camera and crane, which will be installed late this month. Larger swivel units for the animation, inking and painting desk also have been ordered. New cartoon sked calls for subjects to be produced for a 1.75 screen, suitable also for standard showing. Selzer tosses annual Warner Club Christmas party at his home Dec. 20.

Chuck Jones was one of those “key workers;” he had left Disney in November. Tedd Pierce returned as well. He had gone to UPA from Warners well before the shutdown and was replaced with Sid Marcus in the McKimson unit. But Pierce wrote for Jones when he returned; He didn’t write for McKimson right away because only two units operated again when the studio resumed full production. McKimson returned a little later. Variety reported on March 9, 1954.

Warners Expanding Its Cartoon Studio Into Three Units

Warners cartoon studio, which resumed production the first of the year with two units, very likely will be expanded to three following arrival later this month of Norman Moray, Warners' shorts sales [boss].

McKimson’s new unit consisted of Darling, Ted Bonnicksen, a former Disney animator who had been in Freleng’s unit at the time of the shutdown, and Russ Dyson, another ex-Disneyite, who died September 25, 1956 at the age of 50. Thomas handled backgrounds.

Maltese rejoined the studio and the Jones unit at the end of August 1954.

As for MGM, Quimby never did bring back a second unit for theatrical cartoons, but he did have Mike Lah work on the animated segment in the Gene Kelly feature “Invitation to the Dance.” Variety

● Reported on May 27, 1953 a cartoon/live action scene was being considered but hadn’t been filmed,

● Ran a story on August 10th saying it would go ahead,

● Blurbed on March 12, 1954 that Quimby had set a finishing date of June 15th for it but

● Announced on June 8th that Kelly couldn’t shoot it until August.

Lah ended up directing a second unit after Quimby retired around the start of 1956. Meanwhile, Tex Avery landed at Walter Lantz (Daily Variety, Dec. 23, 1953), but lasted only eight months and completed four cartoons.

Warners maintained its cartoon studio into the 1960s, merging it with the commercial and industrial films department under David DePatie. When Variety reported on May 31, 1963 that DePatie-Freleng Enterprises had formed, it stated that what was once the cartoon studio was “a recently dissolved WB subsidiary.” The studio did eventually reopen for a few years, but it just wasn’t the same.

Labels:

MGM,

Walter Lantz,

Warner Bros.

Friday, 5 September 2014

An Upper Berth in the Ross Car

Here’s another one of Paul Julian’s inside gags that caught me by surprise. It’s from “All Abir-r-r-d” (released 1949). You can barely catch it in the frames below; I imagine it would be easier on a Blu-Ray version.

Julian loved hiding names of the members of Friz Freleng’s unit in the background. That happens in the opening animation in the titles of this cartoon. If you can see this first frame well enough, you’ll notice the names on the two rail cars. One is “Ross” and the other in “Champin.” Virgil Ross and Ken Champin were animators on this short.

.png)

And in this shot, the cars are labelled “Frizby” and “Hawley.” Friz Freleng directed the short and Hawley Pratt laid it out (I think the next car simply says “Baggage”).

.png)

As you can see, Art Davis and Emery Hawkins also animated this cartoon. Hawkins had been in the Davis unit before it was disbanded and Artie moved over to Friz’s unit.

Julian loved hiding names of the members of Friz Freleng’s unit in the background. That happens in the opening animation in the titles of this cartoon. If you can see this first frame well enough, you’ll notice the names on the two rail cars. One is “Ross” and the other in “Champin.” Virgil Ross and Ken Champin were animators on this short.

.png)

And in this shot, the cars are labelled “Frizby” and “Hawley.” Friz Freleng directed the short and Hawley Pratt laid it out (I think the next car simply says “Baggage”).

.png)

As you can see, Art Davis and Emery Hawkins also animated this cartoon. Hawkins had been in the Davis unit before it was disbanded and Artie moved over to Friz’s unit.

Thursday, 4 September 2014

Woody in a Frenzy

There are shock takes galore in the Don Patterson-directed “A Fine Feathered Frenzy,” some by Patterson himself.

Patterson and writer Homer Brightman have purloined the story premise from Tex Avery and his writer Rich Hogan. Avery’s wolf couldn’t hide from Droopy; Droopy was always where he went. Wild take followed. Here, Woody Woodpecker can’t escape from the inappropriately-named Gorgeous Gal in her mansion. Wild takes follow.

Here’s one near the end. First the anticipation drawings.

Now, the take. The eyes are widening at a slower speed than in the actual cartoon.

Patterson is hamstrung a bit by Woody’s size. In “Northwest Hounded Police,” the wolf’s takes fill the screen. In this cartoon, Woody is small so some of the takes are harder to see.

There’s irony here. Patterson’s directorial career was ended when Walter Lantz hired someone and shunted Patterson back into animation. Lantz hired Tex Avery.

Patterson and writer Homer Brightman have purloined the story premise from Tex Avery and his writer Rich Hogan. Avery’s wolf couldn’t hide from Droopy; Droopy was always where he went. Wild take followed. Here, Woody Woodpecker can’t escape from the inappropriately-named Gorgeous Gal in her mansion. Wild takes follow.

Here’s one near the end. First the anticipation drawings.

Now, the take. The eyes are widening at a slower speed than in the actual cartoon.

Patterson is hamstrung a bit by Woody’s size. In “Northwest Hounded Police,” the wolf’s takes fill the screen. In this cartoon, Woody is small so some of the takes are harder to see.

There’s irony here. Patterson’s directorial career was ended when Walter Lantz hired someone and shunted Patterson back into animation. Lantz hired Tex Avery.

Labels:

Don Patterson,

Walter Lantz

Wednesday, 3 September 2014

The First TV Announcer

Someone had to be the first host on television. That someone was a person you’ve never heard of. Pioneers tend to get lost in the shuffle on occasion.

Programmes on licensed TV stations go back to the late 1920s but it’s generally conceded that the first continuously broadcasting station in North America was NBC’s W2XBS in New York, which began regular shows on April 30, 1939 (though it was off the air from August 1 to October 26, 1940 for technical work to change frequencies). There were no networks or commercials, and broadcast frequencies and transmission picture standards (lines and frames per second) hadn’t been finalised.

Television is thought of as a visual medium but eventually NBC realised that it would be nice if someone could go on its TV station and say “This is the National Broadcasting Company” and other important things. So Ray Forrest was hired.

The New York Sun profiled him in its edition of April 13, 1940.

The Television Man

Many Were Called, But Ray Forrest Had the Qualifications.

By K. W. STRONG.

It is 8:30 and the beginning of an evening television program. The televisor screen comes to life with a short length of “leader” film announcing the source of the telecast. At its conclusion the screen goes dark for a brief instant and then the head and shoulders of a good-looking young man take gradual form until his image is clear and sharp on the screen. Gazing directly at the viewer the newcomer's face breaks into a likable smile and he begins to explain the forthcoming visual feature. The young man is Ray Forrest, who holds the enviable title of television’s first regular announcer. In the years to come when television history is recorded it is probable that his name will appear in the permanent records along with the Milton Crosses and Tommy Cowans of radio’s earliest days.

Although he is now recognized at sight by every owner of a television set, little has been written about Forrest. He is only 24 years of age, unmarried and with but one hobby—his present job. He attended Staunton Military Academy where he was made cadet major in his senior year. Following his schooling he went abroad for a year to study foreign languages, then returned to America where he fully expected to take up the work of his father, that of watch making. However, a friend of the family who was associated with radio broadcasting invited him to visit the Radio City studios. That happy circumstance represented a complete turn-about in his life. From that time on, it was radio, not watch making, that held his hopes of the future. Fortunately for him, he heard of an opening in the NBC mail room, applied for it and got it. But the work, interesting as it was, did not bring him close enough to the real activities of radio, so he waited his chance and soon found a place on the Guest Relations staff. First he was a page and in the normal order of events, became a guide, one of those upstanding youngsters, college graduates for the most part, who hurry about Radio City studios and lobbies, resplendent in gold braid and chevrons. This was more like it. It was definite progress, but young Forrest still felt that there was some distance to to before he attained his objective.

Makes Junior Staff.

As he performed his daily assignments he watched his opportunities closely and when he heard that an audition for junior announcers was to be held he tried out with numerous other applicants. He was pretty bad, he now admits, in his first attempt but he realised his faults and on the next audition made the grade. In June, 1938, as was made a Junior Announcer which meant that he was given frequent chances on early morning programs to gain experience. The next step would have been an assignment as a regular announcer.

But before this stage was reached television came along and changed his course.

In December, 1939, Forrest was one of several announcers who were sent to the television studio to announce the visual programs which were already under way. Program directors were seeking the right personality for the new, untried field where the requirements differed widely from those of broadcast announcing. It required only a trial or two before Forrest was declared to be the man for the job. He possessed the rare combination of an announcer who televised well and one who could read lines from a script or ad lib them as the occasion demanded. Moreover, unlike many of the outstanding broadcast mike-masters, Forrest did not tighten up when racing the ogling camera lens. To television viewers he seemed to be talking direct to them in a personal manner that was both genial and friendly.

Now that he is established as the NBC Television Man, Forrest is convinced that he is on the way to his goal.

Has Much to Learn.

“But I've still got a lot to learn,” he confesses. “Television is new to most of us on the staff and we learn something with every telecast. All I want to do is to keep on as I am going and eventually become a real good announcer.”

Although his work covers every type of program from matter-of-fact explanations of forthcoming programs to variety shows into some of which he has been thrust as an unintended entertainer, he prefers Special Events such as the telecast from an airplane in which he participated last month. He believes, too, that this field will become of increasing importance as television programs are extended.

On standard broadcasts ad libbing by announcers is frowned upon but in television conditions are different and greater freedom of action is encouraged. “Scripts,” explained Forrest, “may always have to be used by announcers in some cases but the public seems to prefer extemporaneous delivery whenever possible.

“This is so particularly in the variety type of show. An announcer reading from a script can easily shift the mood from one of naturalness to stiffness and the viewer reacts instantly to the change.”

When asked about the effect of the intense lights needed in television studios, Forrest was undisturbed.

“They don’t bother me now. You get used to them after awhile. Those who really feel their effects are probably the victims of their own nervousness. Actually the temperature is not much higher then we all have to stand on an average August day in New York.”

To televise well the television announcer must do something that the broadcast announcer escapes. He must “make-up” for each appearance. Before Forrest goes to the studio for a program be applies a thin facial layer of panchromatic tan or, as it is called, “Number 36,” a term referring to the particular shade of the coating.

As a broadcast listener and not yet a televiewer you may not have witnessed Ray Forrest at work, but you will eventually and you will like him. There is nothing pedantic about his announcing, whatever the nature of the assignment. His clean-cut countenance, topped by an infectious grin has become as much of a television trade mark as the ubiquitous chart which precedes every telecast. But unlike the chart, Forrest is human and gives you the impression of a young man you, would like to invite into the family circle that he seems to be talking to. And that, after all, is about as high a recommendation as any announcer could hope to acquire.

Television carried on during the war, but Ray Forrest disappeared from screens and into the service. He returned in 1946 but the medium was slowly but surely building into an entertainment giant and Forrest was left behind. He died on March 11, 1999. The New York Times paid a lovely and extensive tribute worthy of a pioneer. Read it here.

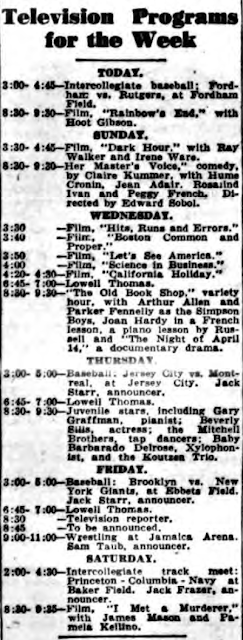

If you’re wondering what was on TV, at least in New York City, when the article was written, you can see the Sun’s weekly summary to your right. The schedule is pretty ambitious, considering there was no commercial revenue and a maximum 4,000 sets that could pick up the station. But things stagnated during the war due to the lack of new TV sets, not to mention little ad income, so programming was eventually cut back. You can see there was a live play on Sunday (April 14th) and variety shows on Wednesday (17th) and Thursday (18th), all mounted for TV alone. Arthur Allen and Parker Fennelly’s names should be familiar as they portrayed old New Englanders in a number of radio shows; Fennelly later played Titus Moody on the Fred Allen show and delighted TV viewers in the ‘60s in a series of Pepperidge Farm commercials. By contrast, NBC radio was airing a variety show (from Chicago) in that slot as well. “Avalon Time” was emceed by Don McNeill and featured mimic Jerry Mann and singer Dick Todd. And, yes, that name in the juvenile revue is Beverly Sills, age 10. She had already appeared on the Major Bowes radio show by then.

The movies weren’t exactly A-list. “The Dark Hour” was a 1936 production by the Chesterfield Motion Picture Corporation. Someone’s posted it on YouTube. “I Met a Murderer” was a 1939 British film with James and the future Pamela Mason (who was married to the film’s director, Roy Kellino, at the time. He later wed June Cleaver, er, Barbara Billingsley). “Rainbow’s End” was a 1935 Western produced by the unaptly named First Division Pictures; Hoot Gibson’s career was into a free-fall by now. The station aired industrial short films like “Boston Common and Proper,” also on YouTube. And the station had a collection of Van Beuren cartoons from 1930 which pop up in other weekly listings. The biggest name the station had was Lowell Thomas, and it was merely simulcasting his radio newscast. And another story in the Sun notes that the Montreal-Jersey City and Giants-Dodgers games were the first opening day baseball matches to be televised.

Programmes on licensed TV stations go back to the late 1920s but it’s generally conceded that the first continuously broadcasting station in North America was NBC’s W2XBS in New York, which began regular shows on April 30, 1939 (though it was off the air from August 1 to October 26, 1940 for technical work to change frequencies). There were no networks or commercials, and broadcast frequencies and transmission picture standards (lines and frames per second) hadn’t been finalised.

Television is thought of as a visual medium but eventually NBC realised that it would be nice if someone could go on its TV station and say “This is the National Broadcasting Company” and other important things. So Ray Forrest was hired.

The New York Sun profiled him in its edition of April 13, 1940.

The Television Man

Many Were Called, But Ray Forrest Had the Qualifications.

By K. W. STRONG.

It is 8:30 and the beginning of an evening television program. The televisor screen comes to life with a short length of “leader” film announcing the source of the telecast. At its conclusion the screen goes dark for a brief instant and then the head and shoulders of a good-looking young man take gradual form until his image is clear and sharp on the screen. Gazing directly at the viewer the newcomer's face breaks into a likable smile and he begins to explain the forthcoming visual feature. The young man is Ray Forrest, who holds the enviable title of television’s first regular announcer. In the years to come when television history is recorded it is probable that his name will appear in the permanent records along with the Milton Crosses and Tommy Cowans of radio’s earliest days.

Although he is now recognized at sight by every owner of a television set, little has been written about Forrest. He is only 24 years of age, unmarried and with but one hobby—his present job. He attended Staunton Military Academy where he was made cadet major in his senior year. Following his schooling he went abroad for a year to study foreign languages, then returned to America where he fully expected to take up the work of his father, that of watch making. However, a friend of the family who was associated with radio broadcasting invited him to visit the Radio City studios. That happy circumstance represented a complete turn-about in his life. From that time on, it was radio, not watch making, that held his hopes of the future. Fortunately for him, he heard of an opening in the NBC mail room, applied for it and got it. But the work, interesting as it was, did not bring him close enough to the real activities of radio, so he waited his chance and soon found a place on the Guest Relations staff. First he was a page and in the normal order of events, became a guide, one of those upstanding youngsters, college graduates for the most part, who hurry about Radio City studios and lobbies, resplendent in gold braid and chevrons. This was more like it. It was definite progress, but young Forrest still felt that there was some distance to to before he attained his objective.

Makes Junior Staff.

As he performed his daily assignments he watched his opportunities closely and when he heard that an audition for junior announcers was to be held he tried out with numerous other applicants. He was pretty bad, he now admits, in his first attempt but he realised his faults and on the next audition made the grade. In June, 1938, as was made a Junior Announcer which meant that he was given frequent chances on early morning programs to gain experience. The next step would have been an assignment as a regular announcer.

But before this stage was reached television came along and changed his course.

In December, 1939, Forrest was one of several announcers who were sent to the television studio to announce the visual programs which were already under way. Program directors were seeking the right personality for the new, untried field where the requirements differed widely from those of broadcast announcing. It required only a trial or two before Forrest was declared to be the man for the job. He possessed the rare combination of an announcer who televised well and one who could read lines from a script or ad lib them as the occasion demanded. Moreover, unlike many of the outstanding broadcast mike-masters, Forrest did not tighten up when racing the ogling camera lens. To television viewers he seemed to be talking direct to them in a personal manner that was both genial and friendly.

Now that he is established as the NBC Television Man, Forrest is convinced that he is on the way to his goal.

Has Much to Learn.

“But I've still got a lot to learn,” he confesses. “Television is new to most of us on the staff and we learn something with every telecast. All I want to do is to keep on as I am going and eventually become a real good announcer.”

Although his work covers every type of program from matter-of-fact explanations of forthcoming programs to variety shows into some of which he has been thrust as an unintended entertainer, he prefers Special Events such as the telecast from an airplane in which he participated last month. He believes, too, that this field will become of increasing importance as television programs are extended.

On standard broadcasts ad libbing by announcers is frowned upon but in television conditions are different and greater freedom of action is encouraged. “Scripts,” explained Forrest, “may always have to be used by announcers in some cases but the public seems to prefer extemporaneous delivery whenever possible.

“This is so particularly in the variety type of show. An announcer reading from a script can easily shift the mood from one of naturalness to stiffness and the viewer reacts instantly to the change.”

When asked about the effect of the intense lights needed in television studios, Forrest was undisturbed.

“They don’t bother me now. You get used to them after awhile. Those who really feel their effects are probably the victims of their own nervousness. Actually the temperature is not much higher then we all have to stand on an average August day in New York.”

To televise well the television announcer must do something that the broadcast announcer escapes. He must “make-up” for each appearance. Before Forrest goes to the studio for a program be applies a thin facial layer of panchromatic tan or, as it is called, “Number 36,” a term referring to the particular shade of the coating.

As a broadcast listener and not yet a televiewer you may not have witnessed Ray Forrest at work, but you will eventually and you will like him. There is nothing pedantic about his announcing, whatever the nature of the assignment. His clean-cut countenance, topped by an infectious grin has become as much of a television trade mark as the ubiquitous chart which precedes every telecast. But unlike the chart, Forrest is human and gives you the impression of a young man you, would like to invite into the family circle that he seems to be talking to. And that, after all, is about as high a recommendation as any announcer could hope to acquire.

Television carried on during the war, but Ray Forrest disappeared from screens and into the service. He returned in 1946 but the medium was slowly but surely building into an entertainment giant and Forrest was left behind. He died on March 11, 1999. The New York Times paid a lovely and extensive tribute worthy of a pioneer. Read it here.

If you’re wondering what was on TV, at least in New York City, when the article was written, you can see the Sun’s weekly summary to your right. The schedule is pretty ambitious, considering there was no commercial revenue and a maximum 4,000 sets that could pick up the station. But things stagnated during the war due to the lack of new TV sets, not to mention little ad income, so programming was eventually cut back. You can see there was a live play on Sunday (April 14th) and variety shows on Wednesday (17th) and Thursday (18th), all mounted for TV alone. Arthur Allen and Parker Fennelly’s names should be familiar as they portrayed old New Englanders in a number of radio shows; Fennelly later played Titus Moody on the Fred Allen show and delighted TV viewers in the ‘60s in a series of Pepperidge Farm commercials. By contrast, NBC radio was airing a variety show (from Chicago) in that slot as well. “Avalon Time” was emceed by Don McNeill and featured mimic Jerry Mann and singer Dick Todd. And, yes, that name in the juvenile revue is Beverly Sills, age 10. She had already appeared on the Major Bowes radio show by then.

The movies weren’t exactly A-list. “The Dark Hour” was a 1936 production by the Chesterfield Motion Picture Corporation. Someone’s posted it on YouTube. “I Met a Murderer” was a 1939 British film with James and the future Pamela Mason (who was married to the film’s director, Roy Kellino, at the time. He later wed June Cleaver, er, Barbara Billingsley). “Rainbow’s End” was a 1935 Western produced by the unaptly named First Division Pictures; Hoot Gibson’s career was into a free-fall by now. The station aired industrial short films like “Boston Common and Proper,” also on YouTube. And the station had a collection of Van Beuren cartoons from 1930 which pop up in other weekly listings. The biggest name the station had was Lowell Thomas, and it was merely simulcasting his radio newscast. And another story in the Sun notes that the Montreal-Jersey City and Giants-Dodgers games were the first opening day baseball matches to be televised.

Tuesday, 2 September 2014

Henpecked Hoboes Sky Shot

Johnny Johnsen came up with some wonderfully creative vertical backgrounds for Tex Avery. It’s a shame the characters get in the way sometimes.

There’s a scene in “Henpecked Hoboes” where a rooster is tied onto a rocket which zooms into the sky. The shot cuts to a great aerial perspective. Here’s as much of the background as I can snip together.

Unfortunately, the rooster gets in the way of the best thing about the background. As the camera pans up the drawing, Johnson effortlessly segues from the mountainous scene to a higher set of snowy mountains and, above that, the uppermost Arctic. These frames below give you a bit of the idea.

One the great mysteries to me is who was handling layouts for Avery when this cartoon was designed in the mid-1940s. Ed Benedict hadn’t arrived yet. Avery is almost given credit for everything except drawing his cartoons that others in his unit are kind of shunted aside, including whoever laid out this background setting.

There’s a scene in “Henpecked Hoboes” where a rooster is tied onto a rocket which zooms into the sky. The shot cuts to a great aerial perspective. Here’s as much of the background as I can snip together.

Unfortunately, the rooster gets in the way of the best thing about the background. As the camera pans up the drawing, Johnson effortlessly segues from the mountainous scene to a higher set of snowy mountains and, above that, the uppermost Arctic. These frames below give you a bit of the idea.

One the great mysteries to me is who was handling layouts for Avery when this cartoon was designed in the mid-1940s. Ed Benedict hadn’t arrived yet. Avery is almost given credit for everything except drawing his cartoons that others in his unit are kind of shunted aside, including whoever laid out this background setting.

Labels:

Johnny Johnsen,

MGM,

Tex Avery

Monday, 1 September 2014

The Winner: Saturn!

Many strange premises populate the old Fleischer studio cartoons, but maybe the strangest the moon auctioning off the planet Earth in “Betty Boop’s Ups and Downs” (1932). There’s no real reason for it to happen other than to spark the string of gravity gags after the bidding war ends.

The moon calls over the nearby planets.

The planets morph into heads to bid on the Earth. First Mars, then Venus, then Saturn. Saturn may have been named for a Roman god but the planet is evidently kosher judging by his accent. Saturn wins the auction (with the lowest bid of $20). He hands over the bag of gelt.

Willard Bowsky and Ugo D’Orsi’s names come up as animators in the rotating Fleischer credit system.

The moon calls over the nearby planets.

The planets morph into heads to bid on the Earth. First Mars, then Venus, then Saturn. Saturn may have been named for a Roman god but the planet is evidently kosher judging by his accent. Saturn wins the auction (with the lowest bid of $20). He hands over the bag of gelt.

Willard Bowsky and Ugo D’Orsi’s names come up as animators in the rotating Fleischer credit system.

Labels:

Fleischer

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)