Someone had to be the first host on television. That someone was a person you’ve never heard of. Pioneers tend to get lost in the shuffle on occasion.

Programmes on licensed TV stations go back to the late 1920s but it’s generally conceded that the first continuously broadcasting station in North America was NBC’s W2XBS in New York, which began regular shows on April 30, 1939 (though it was off the air from August 1 to October 26, 1940 for technical work to change frequencies). There were no networks or commercials, and broadcast frequencies and transmission picture standards (lines and frames per second) hadn’t been finalised.

Television is thought of as a visual medium but eventually NBC realised that it would be nice if someone could go on its TV station and say “This is the National Broadcasting Company” and other important things. So Ray Forrest was hired.

The New York Sun profiled him in its edition of April 13, 1940.

The Television Man

Many Were Called, But Ray Forrest Had the Qualifications.

By K. W. STRONG.

It is 8:30 and the beginning of an evening television program. The televisor screen comes to life with a short length of “leader” film announcing the source of the telecast. At its conclusion the screen goes dark for a brief instant and then the head and shoulders of a good-looking young man take gradual form until his image is clear and sharp on the screen. Gazing directly at the viewer the newcomer's face breaks into a likable smile and he begins to explain the forthcoming visual feature. The young man is Ray Forrest, who holds the enviable title of television’s first regular announcer. In the years to come when television history is recorded it is probable that his name will appear in the permanent records along with the Milton Crosses and Tommy Cowans of radio’s earliest days.

Although he is now recognized at sight by every owner of a television set, little has been written about Forrest. He is only 24 years of age, unmarried and with but one hobby—his present job. He attended Staunton Military Academy where he was made cadet major in his senior year. Following his schooling he went abroad for a year to study foreign languages, then returned to America where he fully expected to take up the work of his father, that of watch making. However, a friend of the family who was associated with radio broadcasting invited him to visit the Radio City studios. That happy circumstance represented a complete turn-about in his life. From that time on, it was radio, not watch making, that held his hopes of the future. Fortunately for him, he heard of an opening in the NBC mail room, applied for it and got it. But the work, interesting as it was, did not bring him close enough to the real activities of radio, so he waited his chance and soon found a place on the Guest Relations staff. First he was a page and in the normal order of events, became a guide, one of those upstanding youngsters, college graduates for the most part, who hurry about Radio City studios and lobbies, resplendent in gold braid and chevrons. This was more like it. It was definite progress, but young Forrest still felt that there was some distance to to before he attained his objective.

Makes Junior Staff.

As he performed his daily assignments he watched his opportunities closely and when he heard that an audition for junior announcers was to be held he tried out with numerous other applicants. He was pretty bad, he now admits, in his first attempt but he realised his faults and on the next audition made the grade. In June, 1938, as was made a Junior Announcer which meant that he was given frequent chances on early morning programs to gain experience. The next step would have been an assignment as a regular announcer.

But before this stage was reached television came along and changed his course.

In December, 1939, Forrest was one of several announcers who were sent to the television studio to announce the visual programs which were already under way. Program directors were seeking the right personality for the new, untried field where the requirements differed widely from those of broadcast announcing. It required only a trial or two before Forrest was declared to be the man for the job. He possessed the rare combination of an announcer who televised well and one who could read lines from a script or ad lib them as the occasion demanded. Moreover, unlike many of the outstanding broadcast mike-masters, Forrest did not tighten up when racing the ogling camera lens. To television viewers he seemed to be talking direct to them in a personal manner that was both genial and friendly.

Now that he is established as the NBC Television Man, Forrest is convinced that he is on the way to his goal.

Has Much to Learn.

“But I've still got a lot to learn,” he confesses. “Television is new to most of us on the staff and we learn something with every telecast. All I want to do is to keep on as I am going and eventually become a real good announcer.”

Although his work covers every type of program from matter-of-fact explanations of forthcoming programs to variety shows into some of which he has been thrust as an unintended entertainer, he prefers Special Events such as the telecast from an airplane in which he participated last month. He believes, too, that this field will become of increasing importance as television programs are extended.

On standard broadcasts ad libbing by announcers is frowned upon but in television conditions are different and greater freedom of action is encouraged.

“Scripts,” explained Forrest, “may always have to be used by announcers in some cases but the public seems to prefer extemporaneous delivery whenever possible.

“This is so particularly in the variety type of show. An announcer reading from a script can easily shift the mood from one of naturalness to stiffness and the viewer reacts instantly to the change.”

When asked about the effect of the intense lights needed in television studios, Forrest was undisturbed.

“They don’t bother me now. You get used to them after awhile. Those who really feel their effects are probably the victims of their own nervousness. Actually the temperature is not much higher then we all have to stand on an average August day in New York.”

To televise well the television announcer must do something that the broadcast announcer escapes. He must “make-up” for each appearance. Before Forrest goes to the studio for a program be applies a thin facial layer of panchromatic tan or, as it is called, “Number 36,” a term referring to the particular shade of the coating.

As a broadcast listener and not yet a televiewer you may not have witnessed Ray Forrest at work, but you will eventually and you will like him. There is nothing pedantic about his announcing, whatever the nature of the assignment. His clean-cut countenance, topped by an infectious grin has become as much of a television trade mark as the ubiquitous chart which precedes every telecast. But unlike the chart, Forrest is human and gives you the impression of a young man you, would like to invite into the family circle that he seems to be talking to. And that, after all, is about as high a recommendation as any announcer could hope to acquire.

Television carried on during the war, but Ray Forrest disappeared from screens and into the service. He returned in 1946 but the medium was slowly but surely building into an entertainment giant and Forrest was left behind. He died on March 11, 1999. The New York Times paid a lovely and extensive tribute worthy of a pioneer. Read it here.

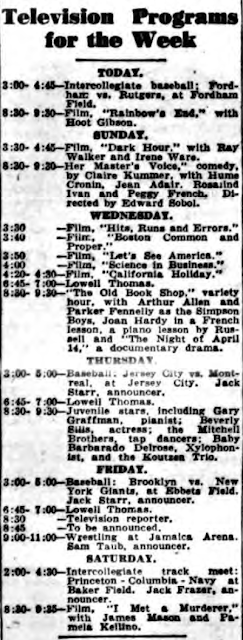

If you’re wondering what was on TV, at least in New York City, when the article was written, you can see the Sun’s weekly summary to your right. The schedule is pretty ambitious, considering there was no commercial revenue and a maximum 4,000 sets that could pick up the station. But things stagnated during the war due to the lack of new TV sets, not to mention little ad income, so programming was eventually cut back. You can see there was a live play on Sunday (April 14th) and variety shows on Wednesday (17th) and Thursday (18th), all mounted for TV alone. Arthur Allen and Parker Fennelly’s names should be familiar as they portrayed old New Englanders in a number of radio shows; Fennelly later played Titus Moody on the Fred Allen show and delighted TV viewers in the ‘60s in a series of Pepperidge Farm commercials. By contrast, NBC radio was airing a variety show (from Chicago) in that slot as well. “Avalon Time” was emceed by Don McNeill and featured mimic Jerry Mann and singer Dick Todd. And, yes, that name in the juvenile revue is Beverly Sills, age 10. She had already appeared on the Major Bowes radio show by then.

The movies weren’t exactly A-list. “The Dark Hour” was a 1936 production by the Chesterfield Motion Picture Corporation. Someone’s posted it on YouTube. “I Met a Murderer” was a 1939 British film with James and the future Pamela Mason (who was married to the film’s director, Roy Kellino, at the time. He later wed June Cleaver, er, Barbara Billingsley). “Rainbow’s End” was a 1935 Western produced by the unaptly named First Division Pictures; Hoot Gibson’s career was into a free-fall by now. The station aired industrial short films like “Boston Common and Proper,” also on YouTube. And the station had a collection of Van Beuren cartoons from 1930 which pop up in other weekly listings. The biggest name the station had was Lowell Thomas, and it was merely simulcasting his radio newscast. And another story in the Sun notes that the Montreal-Jersey City and Giants-Dodgers games were the first opening day baseball matches to be televised.

No comments:

Post a Comment