Once sound came in, the big movie studios all had cartoons as part of their release schedule. The Poverty Row studios didn’t—with one exception.

Republic Pictures made two brief attempts to release cartoons.

The Film Daily announced on June 25, 1946 it had signed a deal with Bob Clampett Productions for 12 cartoons. The trade paper’s next word on the subject was over a year later, when it reported on August 27, 1947 the deal with Clampett was down to four cartoons. “A Grand Old Nag” was made it to screens in December and that was it.

In the meantime, someone else had approached Republic about cartoons, someone without long experience in animation like Clampett. This is from

The Film Daily of November 19, 1946.

Impossible Lowers Costs With New Cartoon Technic

Impossible Pictures feels that it has almost done the impossible with its first effort, "Romantic Rumbolia," Prexy Leonard Levinson pointed out yesterday in explaining why he and Vice-President David Flexner had entered the cartoon field at a time of spiralling costs and inadequate rentals.

Levinson said that despite the added expense of making the cartoon short in Anscocolor, company was able to achieve economies by using a different approach both in technique and in subject matter. "Rumbolia," he observed, is the starter in a series of 12 "Jerky Journeys" a year, to be distributed by one of the majors. Negotiations get under way this week.

Levinson's background has been mostly in radio — he originated "The Great Gildersleeve" show, and for three years co-authored "Fibber McGee and Molly." Flexer operates a chain of 14 standard theaters in the South, plus two drive-ins. By 1949, he plans to operate 23 more. Flexer has been in exhibition since 1932. Before that he had been a UA salesman in the Pittsburgh territory.

“Jerky Journeys” was an appropriate name. The cartoons didn’t feature the fluid animation of Disney or even low-budget Terrytoons. They were limited animation. And cheaper animation, something that suited a Poverty Row studio just fine.

The Film Daily mentioned in its issue of May 13, 1948.

Impossible's Cartoons Get Rep. Distribution

"Jerky Journeys" cartoon produced by Impossible Pictures, Inc., headed by Leonard Levinson and Dave Flexer, will be distributed, starting July 1, by Republic, deal being announced jointly yesterday by Herbert J. Yates and Levinson. Four of the shorts, in Trucolor, will be made in the first year of the agreement, which runs for seven years with annual options. Frank Nelson, from radio, will do the narration for the shorts which stress camera animation rather than figure animation.

Besides being a comedy writer, Levinson was a promoter. He’d already been advertising the cartoons on a satiric local radio show in September 1947. Like Jay Ward about a dozen years later, he sent out funny news releases and organised an unusual promotional junket for reporters. Here’s a piece by Thomas F. Brady in the

New York Times of November 30, 1947:

Come On In

Leonard L. Levinson, who formed a film company named Impossible Pictures early this year, left Hollywood three weeks ago with a print of the company's first animated cartoon in an improbable series to be called "Jerky Journeys." Mr. Levinson's destination was New York City, but apparently he never arrived. The other day this department received the following telegram from David Flexer, vice president of Impossible: "Leonard L. Levinson, our president, refuses to take one step beyond Paterson, NJ, until THE TIMES heralds his arrival in New York City. Wish you could do something, as we need him here for negotiations with film distributing companies on our 'Jerky Journeys.'" Shriek, oh whistles! Mr. Levinson shall cross the Hudson.

Still, it took some time for the cartoons to make it to screens. Erskine Johnston’s column of November 11, 1948 had this squib:

HOPER for: Len Levinson winning some sort of Academy recognition for the new technique in his Republic cartoon series. An average eight-minute cartoon requires 10,000 individual drawings. Len does it with only 500. The Three Minnies, is clocking 10 laughs a minute at sneak previews.

The facetious “Oscar” hunt was expounded on by Aline Mosby of the United Press in a January 24, 1949 column in which Levinson joked “the society for the preservation of cigar store Indians in Bellevue, Wash., has honored ‘The Three Minnies’ as the best picture about cigar store Indians made in 1948.”

Here are some full columns that came thanks to Levinson’s press agentry. First, an Associated Press column from February 17, 1949.

Sights and Sounds From Hollywood

By GENE HANDSAKER

HOLLYWOOD—Leonard Louie Levinson is a moon-faced gent who does screwball things. Actually, he's screwy only in the way a fox is.

At Christmas he sent war-surplus dust-respirator masks to the 15 city councilman of haze ridden Los Angeles. A card wished them "a coughless Christmas and a smog-free New Year".

Levinson heads a new movie cartoon concern called Impossible Pictures, Inc. He issues publicity bulletins like the following exclusive: "The film called 'No Title Yet' is 15 days ahead of schedule before it started—because we cancelled the picture."

Levinson, 44, a former writer for Lum ‘n’ Abner, Fibber McGee and other leading radio shows, enjoys poking pins in Hollywood’s self-worshipping stuffiness. "Holding a cracked mirror up to Hollywood procedure," he calls it.

He is president, publicity director, movie director, writer, personnel department and paymaster of his firm. It occupies a cluttered nine-by-nine room whose biggest wall sign says, "Don't go away mad, just quietly". He calls it Impossible Pictures because he set out 20 months ago to do several things which established cartoon producers said were impossible.

"They're just breaking even," Levinson says. "I decided to find excuses for not using animation."

An Impossible eight-minute cartoon requires about 400 sketches against 30,000 for a comparable Disney.

"Romantic Rumbolia", one of four completed "Jerky Journeys", shows a Latin seaport at the siesta hour. With everybody asleep, no animation is required. The camera mopes into the capitol building and traces the country's history on the murals. In "Bungle In the Jungle", an animated lion swallows the camera, blacking out the screen. The story goes on in still pictures supposedly made with a box camera—more animation saved.

Levinson has introduced what he calls a picture pun. A character is described by the narrator as having "a raft of friends". Sure enough, he's standing on a group of floating people lashed together. When Capt. Kidd sacks the city of Nisatra—Sinatra spelled sideways—he stuffs it into sacks. The hero of the "Three Minnies--Sota, Tonka, and Haha"—is Watha-hia a backward Indian brave.

Levinson expects to call back his dozen full and part-time employees soon for a ballet cartoon inspired by "Red Shoes" He'll call it "Loose Tights". Or maybe he's only kidding.

As for the junket, here’s a United Press story from 1949.

Junket for Newsmen Not Usual Thing

By ALINE MOSBY

HOLLYWOOD, May 25 (UP)— The Hollywood press, which is feted at lavish movie premiere junkets from Texas to Paris, has just returned from the shortest, smallest and cheapest junket in history—a premier on a streetcar.

This ail-expense-paid trip was staged by a little cartoon company, Impossible Pictures, Inc., whose slogan is, "if it’s a good picture it’s Impossible."

"This is the poor man's McCarthy junket," announced Impossible Chief Leonard Levinson. "Not being able to compete with Glen McCarthy, who moved half of Hollywood to Texas for his premier, we are doing the opposite."

Forty-six travelers (McCarthy had 600) gathered for this excursion at the Hollywood Brown Derby, where dessert was served. Impossible Pictures could not afford a full-course meal, Levinson explained.

Then a bus took the junketers seven blocks to a streetcar named Impossible, which was parked in the shadows of RKO and Paramount studios, home of flashy premiers. A battery of two cops held back the teeming crowd of 15 citizens who waved goodbye as the party hopped aboard. A television camera recorded this event.

Each traveler was furnished with one (1) sack of popcorn.

"This is crazy," observed one cop.

The Los Angeles transit lines had lavishly appointed the streetcar by yanking out hanging-on poles so the view of the riders would be unobstructed. "This Is Impossible" was painted on the side of the trolley and a pair of crossed-eyes decorated the front. The movie screen was taped onto the fare box behind conductoress Virginia Hill, who said she'd never done anything like this before.

As the streetcar dinged through traffic, film critics settled back for four eight-minute cartoons appropriately titled, "Jerky Journeys," or "Authentic Travelogs About Imaginary Places."

The movies also were viewed by a convoy of startled motorists and at stop lights by pedestrians who undoubtedly now believe all streetcars show movies.

The two-mile junket halted 45 minutes later in the wilds of downtown Los Angeles, a faraway point at least to the Hollywood press. Then a bus took everybody home again.

"The junket cost only $118" beamed Levinson. "McCarthy spent half a million. My next premiere will be on an elevated train in New York."

According to

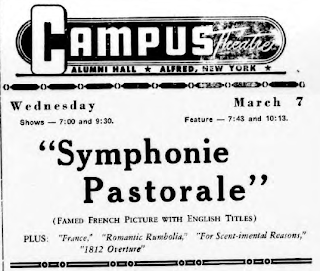

Boxoffice magazine, “Beyond Civilization to Texas” was released March 15, 1949, “The Three Minnies” on April 15, 1949, “Romantic Rumbolia” on June 1, 1949 and “Bungle in the Jungle” two weeks later. The

Boxoffice review of the latter mentions it “has the voice of radio’s Senator Claghorn,” the 1949 Copyright Catalogue mentions Claghorn in its summary and an AP story on Levinson’s studio dated December 12, 1948 insists it’s Delmar, though there’s no voice credit on the cartoon. Frank Nelson gets a narration credit on the other three. Artists Art Heinemann, Pete Alvarado, Paul Julian and Bob Gribbroek get screen credits in addition to Levinson. Those names should all be familiar from Warner Bros. cartoons.

Unfortunately, the late ’40s were not a great time for the animated cartoon and things wouldn’t get better. Columbia closed its studio. Warners and MGM got rid of units. Almost everyone was reissuing old cartoons to fill release schedules. No doubt a smaller studio like Republic felt it no longer could afford the luxury of even limited animation so the option on the Jerky Journeys was dropped. Republic’s foray into animation remains an obscure trail in the road network of Golden Age cartoons.

P.S.: Our thanks to Jerry Beck for the picture at the start of this post. His old web site has an informative post on the Jerky Journeys, though a link to one of the four cartoons is now dead.