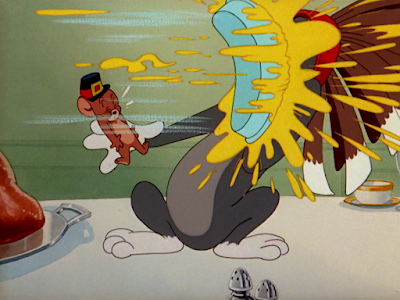

This brings on a very swift cat vs mice war. For about the next 2½ minutes, Tom is bashed in the face with a champagne cork, stabbed in the butt with a fork launched from a tempting dish of delicious Jell-O (note the dry-brush), smacked with a spoon, swallows a boomeranged decorative bulrush he set on fire and splooshed in the face with a crème pie (we will guess it is banana).

Nibbles then fires a candle which lands on the cat’s tail. The flames go up his body and turn him into a black kid, complete with curls on his head. Someone will have to explain why this is funny. I don’t get it. (At least Scott Bradley didn’t put “Old Black Joe” in the background soundtrack like he would have in a Tex Avery cartoon).

Finally, a champagne bottle is popped open. The force of the bubbles turns it into a rocket that bams into Tom’s head, sending him flying.

There’s a crash. It’s off-camera. We see Jerry and Nibbles reacting to what we can’t see, as the camera shakes. It’s just like in a Pixie and Dixie cartoon of a decade later.

Mr. Jinks, er, Tom, is no longer a stereotype as he waves a flag of surrender.

The final scene shows the three giving Grace like good little Christians.

Someone at MGM smelled Oscar-bait with this film. It was shoved into a theatre to make it eligible for an award for 1948. The Miami Herald reported on December 8th.

HOLLYWOOD, Cal.—Preview reaction to M-G-M’s Tom and Jerry cartoon, “The Little Orphan,” resulted in the birth of a new star—Nibbles, baby mouse with ravenous appetite. Result—Nibbles series with William Hanna and Joseph Barbera co-directing. Fred Quimby producing.Indeed, the cartoon did win the Academy Award for Best Short Subject (Cartoon). (1948 was the year Warners released What Makes Daffy Duck?, Back Alley Oproar and Bugs Bunny Rides Again. Not one was nominated. Boo).

You can see Quimby accepting the award below. I like how they didn’t waste time at the Oscars back then with endless speeches. Besides, what would Quimby say? “I really had nothing to do with making this cartoon. I’m just a mid-level executive.”