He was a tinkerer, too, and filed for a patent for an automatic slide projector in 1934.

Here's a link to his patent application. It's not all that exciting, but what do you expect from a patent application?

Brunish was born in the Bronx on Dec. 18, 1902. The 1920 Census reports he was a 17-year old fashion sketcher (a 1925 classified ad in the New York Times is below). In 1930, the Detroit city directory gives his occupation as the vice president of the Consolidated Advertising Corp. He didn’t remain in Detroit long. The next year, his family was living in San Diego, where was employed as Consolidated’s art director. He was living in Los Angeles the following year. The City Directory in 1933 lists him as “artist,” and various Voters Lists from 1936 onward give his occupation as “art director.” He was the chief sound engineer and art director for the Royal Revue Film Studio in Hollywood in 1938. Brunish belonged to the Laguna Beach Art Association and there were showings of his work in the mid-1930s.

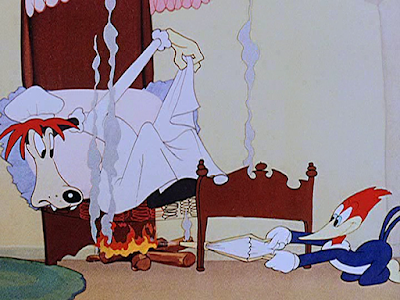

The 1940 Census says “cartoon picture studio artist.” Walter Lantz cartoons didn’t credit any background artists until 1944 and Brunish’s name doesn’t appear ON screen until the end of 1946, when he is credited on The Wacky Weed. However his 1942 Draft Registration states he was employed at Lantz, and the photo of him above is from when he was working on war-time films for the studio. Late Note: Devon Baxter mentions Joe Adamson's notes state Brunish started work at Lantz on Oct. 24, 1937. Joe wrote a fine biography of Lantz, so he would know.

That year, he was involved with the Motion Picture War Chest drive that year. He also contributed in 1942 to “Communique,” a weekly publication by the Hollywood Writers Mobilization for Defense in cooperation with the Office of Emergency Management. Brunish designed posters alongside Cy Young, Tom McKimson, Frank Tipper, Ozzie Evans, John Walker, Chuck Whitton (both at Lantz) and Ed Starr (later of Screen Gems and Sutherland). In 1947, his watercolour “Sunset on the Pacific” was displayed at the Screen Artists show at the Los Angeles Art Association galleries. Other artists who exhibited works may be familiar from various cartoon studios, including Starr, Ralph Hulett, Basil Davidovitch, Barbara Begg and George Nicholas.

The Lantz studio shut down because of a cash crunch in 1949. In the 1950 census, dated April 5, Brunish is listed as a cartoonist who wasn’t working. When Lantz resumed full operation, Brunish was back. The last cartoon with his name on it was The Great Who-Dood-It, released Oct. 20, 1952 (one of his backgrounds is reconstructed below).

Brunish died on June 25, 1952 of cirrhosis of the liver. His Los Angeles Times obit mentions nothing of his patent or his film work; it lists him as a "landscape artist" and that he left behind a widow, a son and a sister.

Note: this is a reworking of a post that appeared on the late GAC forums.