Blitz Wolf isn’t just another Tex Avery fairy tale send-up. There’s a war on, so it’s a propaganda cartoon, too. Considering what a detestable individual Adolf Hitler was, ridiculing him was completely warranted. At the end of the short, the wolf Hitler-stand-in is blown to Hell, which, for him, is populated by Jews (doing their version of the Kitzel catchphrase from the Al Pearce radio show).

Avery, being the anti-Disney, uses Disney’s

Three Little Pigs as a starting point, even utilising the voice of the Practical Pig, Pinto Colvig, to repeat his performance.

The story by Rich Hogan has a warning at the beginning—that even good people can be sucked in by the promises and talk of Fascists. The army-fatigued practical pig warns his brothers to be prepared for the invasion of the Big Bad Wolf, and pulls out a newspaper with the story.

Cut to a close-up and downward pan.

The delusional pigs don’t believe the mainstream media. It doesn’t reflect their beliefs as fact. “He won’t hurt us, ‘cause we signed a treaty with him!” They pull out the treaty. Cut to another close-up and pan, then the camera trucks in a little closer to get the signature and seal.

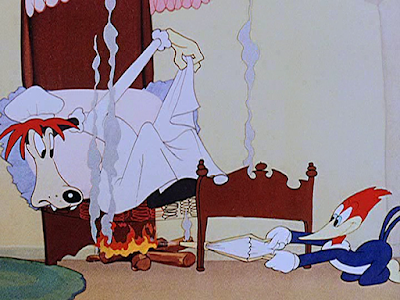

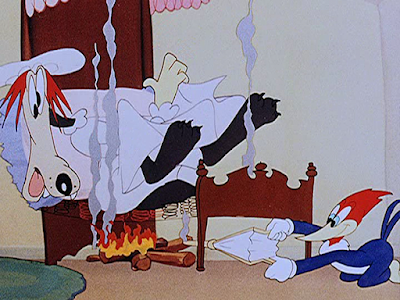

No sooner does this happen than the tanks start rolling in. The scene soon switches to the Blitz Wolf (Bill Thompson with a German accent) shouting to the pig inside the straw house that he’ll huff, etc. “But Adolf, that would break our treaty,” says the pig. “You’re a good guy. Why, you hate war. You wouldn’t go back on your word!” The wolf leans in and says “Are you kiddin’?” and laughs knowing he has snowballed them with his lies.

A little over a month after Pearl Harbor,

The Hollywood Reporter revealed “As his first cartoon supervising chore at MGM, Fred ‘Tex’ Avery will handle ‘Blitz Wolf,’ a new animated character for the studio’s shorts” (Jan. 16, 1942). The paper announced on June 2 the cartoon was “in last stages of work” and on Aug. 19 it was “winding up production.” It wound up pretty fast as the same day, the Academy of Motion Pictures screened it at the Filmarte Theatre.

In fact, it was already in theatres, as an ad from the Portsmouth (Virginia) Herald issue of Aug. 16 shows. (Come for Bing. Stay for the Nazi).

This brings us to the oft-told tale that Fred Quimby thought Hitler might win the war and wanted the cartoon to be a little less violent. Did he really say that?

You’d think maybe the famous 1975 animation issue of

Film Comment might have mentioned the quote. Or Joe Adamson in his interview with Avery in

Tex Avery, King of Cartoons. Or Michael Barrier in his lengthy book

Hollywood Cartoons.

It appears the story started circulating from an interview Chuck Jones did on the Mark and Brian radio show in Los Angeles in 1996 as related in the book

Chuck Jones Conversations (2005, University of Mississippi Press). I quote Jones, quoting Avery, quoting Quimby.

And he [Quimby] went on, he said, “I was just looking at the storyboard of the Blitz Wolf” and he said—“you think,” this is 1944, right in the middle of the war [sic]—and he said, “Do you think you're being a little rough on Mr. Hitler? ‘Cause we don't know who's going to win the war.”

I have a hard time believing Quimby said this, even if he were joking (Quimby was not known for having a sense of humour). Hollywood—as was all of America—was awash with extreme anti-Axis patriotism. And Jones was not exactly known for a kindly attitude toward cartoon film producers (Disney, excepted).

Blitz Wolf was nominated for an Oscar. Three other war-related animated shorts were nominated, with Uncle Walt picking up the statue for

Der Fuehrer’s Face. Fortunately, his face, and the rest of him, was gone in three years.