Cartoon studios were already cutting back operations in the late 1940s. MGM and Warner Bros. closed units, Screen Gems was shut down altogether and Walter Lantz stopped production for a little over a year.

Meanwhile, television was growing, especially in New York and Los Angeles, and as stations signed on, advertisers jumped on board. One thing they found was they could get their message across using animation (they didn’t believe the hooey that cartoons were only for kids), so a number of the Golden Age animators set up their own studios, providing places of employment for former co-workers through the 1960s.

I love animated commercials of this era. Thousands were made but only a handful seem to be out there to view. Amid Amidi’s wonderful book

Cartoon Modern examines the period.

Television Age magazine came out monthly and not only published news about the commercial houses (live action and animation) but provided frames from the spots. It’s a shame the issues available on line are low resolution so you can’t get a great view of what the artwork looked like, but here are some examples from the May 16, 1960 edition.

I won’t try to go through a dissertation about the companies mentioned above; all top-flight operations. Off the top of my head, Adrian Woolery of UPA was the man behind Playhouse, with Bill Melendez as one of the directors. Jack Heiter—who is still out there—was one of the people behind Pantomime. Pelican was one of the companies which put Jack Zander in charge of its animation. Earl Klein was behind Animation, Inc., but Irv Spence and Ed Barge were there, too. Abe Liss, formerly of UPA, started Elektra (it was responsible for the NBC “Living Color” Peacock animation). Ray Favata had designed spots for several studios, including Academy Pictures in New York. And Ray Patin had been a Disney striker.

Among the stories about commercials in this edition:

Two designers for Robert Lawrence Animation two weeks ago exhibited close to 50 of their paintings at the company’s studios, just to prove, apparently, that there’s no conflict between art and commercialism. Both men—Cliff Roberts and George Cannata—design animated tv commercials during working hours. Mr. Roberts, who holds five awards for designs of commercials and industrial films, is also a book illustrator, and he recently held a one-man show at Long Island University. Mr. Cannata has had his paintings exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art three times since 1955. He was cited for his designing of a Lestoil commercial at the International Advertising Film Festival at Cannes in 1959 and has also won numerous Art Directors Club awards.

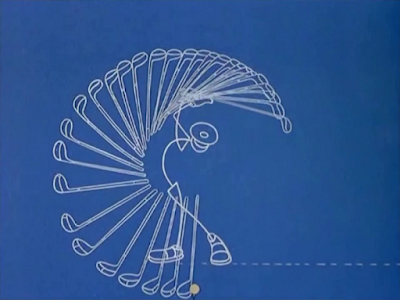

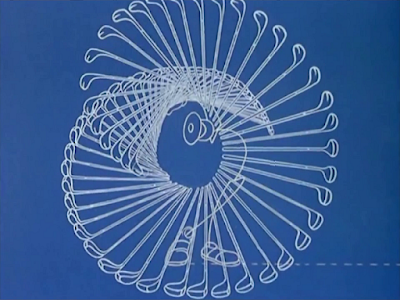

Ray Patin Productions is producing a series of semi-abstract animated color spots for Hudepohl Beer (Stockton, West, Burckhart, Cincinnati). The spots, to be telecast in color, will be seen in regional broadcasts of the Cincinnati Redlegs baseball team.

The first annual International Animation Film Festival will be held in Annecey, France, from June 7 to 12.

Several appointments have been made by UPA Pictures, Inc. Jerry Hathcock has been named supervising director for all animation, Errol Gray has been appointed to the post of production supervisor, and Robert F. Kemper has been signed as mid-western representative for the company. Mr. Kemper, who will also continue to represent Jerry Fairbanks Productions, headquarters in Chicago.

A number of new series of Ford commercials, including one introducing the “Linus” character to television, is being prepared by Playhouse Pictures. In addition to the “Linus” spot for Falcon, they include two two-minute “Peanut” spots and two more “Shaggy Dog” commercials. All are in color. The agency is J. Walter Thompson, New York.

Format Films, formed by Herbert Klynn last year, now has more than 40 employes and is preparing to move into a new studio in Studio City. The company has just completed six more spots for Folger’s coffee (Fletcher, Richards, Calkins & Holden, San Francisco) utilizing a coffee-bean character.

Animation, Inc., is producing two more spots featuring a talking cow for the Michigan Milk Producers Association (Zimmer, Keller, & Calvert, Detroit). The first in the series won a Chicago Art Directors gold medal last year.

We’re going to make a left turn away from ‘50s commercials because I found some stuff on Ray Patin I want to pass along. The story below was published in the Lafayette, Louisiana

Daily Advertiser of March 28, 1930. Patin and his parents had been in Los Angeles for 11 years at this point. He was working as a clerk at an car dealership.

Ray Patin, Former1y Of This City, Making Good Progress On The Road To Art Fame

Engaging in drawing as a side-line occupation for the present but intending to adopt it as his profession later, Ray Patin, formerly of Lafayette, now residing in Los Angeles, California, has already made considerable progress along the road that leads to fame in art.

Many Lafayette citizens will remember Mr. Patin as a boy. His father was at one time a local newspaperman.

“As much as I like art work I haven’t yet gone into it professionally,” Mr. Patin writes a friend here. “However, I am preparing myself, through night study, and all the spare time I can find, to some day make a big splash into it and bat s thousand per cent from the start. My greatest ambition is to become a strip artist, not of the ‘slap stick’ variety, but the ‘Big league’ type with drawings and stories of real value, educationally and entertainingly. However, it’s mighty hard to say just what type of art work I will fall into. It’s easy to say you’ll do a thing but still another proposition to ‘put out the stuff’ and prove you’re all that you boast of yourself. I’ll keep plugging though, and if ‘stick-to-it-iveness’ is the right road to success than I should stand some chance, as I have led to buckle down real seriously to the work that has always been my hobby.”

Born in Breaux Bridge, Mr. Patin, who is 24 years of age, spent eight years of his early childhood in Lafayette. The family then moved to the west, and eventualy [sic] located at Los Angeles.

“We like it out here an awful lot but we can never forget our old friends and my dear relatives in Lafayette and Louisiana,” Mr. Patin states.

The young artist received most of his training as a cartoonist on the staff of the paper published at the high school he attended In California, to which he contributed a cartoon weekly. Far [for] a while he also drew a weekly comic strip in the Junior Secetion [sic] of the Los Angeles Times but was forced to disctontinue [sic] this for lack a time. He was submitted to the Los Angeles Herald seven or eight cartoons, most of which have been accepted. One is reproduced on this page. He has also turned to more serious themes than cartoons, and has produced a series of etchings of southern California missions.

The young artist received most of his training as a cartoonist on the staff of the paper published at the high school he attended In California, to which he contributed a cartoon weekly. Far [for] a while he also drew a weekly comic strip in the Junior Secetion [sic] of the Los Angeles Times but was forced to disctontinue [sic] this for lack a time. He was submitted to the Los Angeles Herald seven or eight cartoons, most of which have been accepted. One is reproduced on this page. He has also turned to more serious themes than cartoons, and has produced a series of etchings of southern California missions.

“I have always liked to draw,” the former Lafayette boy declares. “In fact, the desire to have a pencil in my hand and something to draw on put me into quite a few ‘pickles’ at school when friend found something else behind a geography book besides an inattentive pupil.”

Mr. Patin comes by his artistic talents naturally, for his father Maurice Patin, is well-known to many residents of this section as an able writer. and also skilled as an amateur artists. The father was for several years connected with the former Daily press here and later with the Lafayette Gazette which was purchased by the Daily Advertiser.

Patin’s first animation commercial on television appears to have aired on June 25, 1948, back when Los Angeles still had only two stations. The

Times wrote:

A telecast over KTLA at 7:14 tonight by Security-First National Bank will probably be the first commercial television program sponsored by a bank, the Financial Republic Relations Association said today.

The program will be an animated film on checking accounts made by Ray Patin, former Disney artist, under the supervision of Foote, Cone and Belding.

The “program” would have aired during the Judy Splinters Show. Considering the air time and the fact an ad agency was overseeing it, as opposed to an industrial client, I presume it was a commercial.

While this was going on, Patin was drawing a daily strip for a group called the Artists Associated Syndicate. This appears to have been a joint venture of some animators—Gus Jekel (Patin’s designer), Gil Turner, Dick Moores, Fred Jones, “Mitchell” (ex Warners writer Dave Mitchell aka Milt Kahn?), Jerry Hathcock and “Bob Dalton” (Bob McKimson and Cal Dalton?) were among the artists; most, but not all, the small papers that picked up the strips were in California. This one is from Feb. 20, 1948.

Milford, by the way, was an animated character. Patin had him star in TV spots that ran in the early 50s during

Industry on Parade on a station in Oklahoma City (whether Milford was on the KTLA commercial, I don’t know).

Patin also designed a character for a beer can. Ray Patin Productions animated commercials for the Rainier Brewing Co. that aired in the Pacific Northwest.

Work began drying up for animated commercial studios as the 1960s wore on. Clients switched to live action, which had become less expensive. Patin’s operation, which had been at 6650 Sunset Blvd., ended up at 3425 Cahuenga Blvd., almost across from Hanna-Barbera’s new brand-new studio. In 1967, 45 members of H-B’s commercial and industrial division moved to the other side of the street into the now-empty Patin building. When Patin Productions closed, I don’t know.

Patin died January 17, 1976 in Panorama City, age 69.

I was just about to put this post to bed, but have discovered Ray Patin's daughter Renee has a website. She's written an autobiography. You can check out her site

at this link.