Two cartoons with wonderfully weird Martian landscapes made appearances around the same time in the early days of sound. Oswald the rabbit went to the planet in the Universal short

Mars (released Dec. 29, 1930; copyright Jan. 5, 1931), while one of the many versions of the Fleischers’ Bimbo landed there in

Up to Mars (released Nov. 22, 1930; copyright Nov. 20, 1930).

The

Motion Picture News wasn’t altogether happy with it. A review on its release date says: “Good, But Misses. Dave Fleischer didn’t do as well in this Talkartoon as the subject matter would have permitted. His Mars figures are amusing, but only in a mild way when the opportunity to make them really fantastic was there awaiting execution. However, this will get by nicely.

Regardless, there’s imagination behind the mushrooms, castles, tree stumps and teepees which populate the landscape.

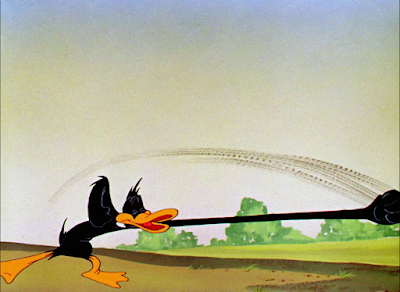

You think Bimbo is drawn by different animators in these frames?

It’s tough to see on this low-res video file, but there’s kind of a tree with gloves at the end of each branch in the background. It reminds me of something you’d find in Bob Clampett’s great

Porky in Wackyland (1938).

Some great Martian designs. There are “reversal” gags. The log saws the saw in half, the crook gives valuables back to someone and a letter doesn’t fit in a mailbox, so the gooney character puts in the mailbox inside the envelope.

Eccentric dancing on Mars. The twins have candles on their heads, similar somewhat to characters in

Bimbo’s Initiation (1931). Another Martian has no body, but legs with minds of their own and detach from his hands.

Guards with lightbulb noses.

I’d love to know more about the nonsense song they’re singing (Oh, for a cue sheet!). How many songs rhyme “consommé” with “Mandolay” and “Oy vey!” and include the words “Nabisco” and “Toronto”?

One more character.

Unfortunately, the background artist is unidentified. Rudy Zamora and Shamus Culhane are the credited animators.