Ink and paint departments were pretty anonymous in the Golden Age of Cartoons. They did top work, though. I especially admire dry-brushing work in the various studios, especially MGM.

Here’s an example from Walter Lantz’s The Screwdriver, a 1941 cartoon where Woody Woodpecker drives an authority figure crazy. You can see some of the drybrush work in one scene where Woody demonstrates speeding to a cop. There are also outlines of wheels; outlines find their way all through the cartoon.

Mel Blanc supplies all the voices (okay, there are only two characters), while Alex Lovy and Ralph Somerville are the credited animators. Bugs Hardaway and Jack Cosgriff are responsible for the story. Woody soon outlived authority-figure heckling, taking on stronger challengers like a hungry cat, a pal-sy wolf and Buzz Buzzard as wonderfully portrayed by Lionel Stander.

Friday, 10 February 2023

Thursday, 9 February 2023

Can't See the Characters For the Trees

Tex Avery didn’t originate the “large body behind thin tree” gag, but he seems to have liked using it. All he and his gag writers had to do was find variations on it so it wouldn’t be stay.

Let’s see how he handled it in The Screwy Truant, a 1945 MGM release.

Here’s the basic gag.

Now, the variations.

Tex tries the body-parts-run-between-the-elms gag. The tail hops.

By now, Tex’s pace was fast enough that you didn’t have time to think about the gag.

Preston Blair, Ed Love and Ray Abrams are the animators.

Let’s see how he handled it in The Screwy Truant, a 1945 MGM release.

Here’s the basic gag.

Now, the variations.

Tex tries the body-parts-run-between-the-elms gag. The tail hops.

By now, Tex’s pace was fast enough that you didn’t have time to think about the gag.

Preston Blair, Ed Love and Ray Abrams are the animators.

Wednesday, 8 February 2023

Come and Knock On Her Door.

The young woman you see to the right had trouble getting sex.

We should qualify this. It was in a TV role she couldn’t get sex. And the show aired a little more than 35 years after this picture was taken.

She made her motion picture debut in 1941 opposite Ronnie Reagan in Warner Bros.’ The Flight Patrol, but was on the New York stage by the end of the year. You know her best as Mrs. Roper.

Three’s Company was Audra Lindley’s biggest success and led to a spin-off series starring her and TV husband Norman Fell. It debuted in 1977, which proved to be a busy and not altogether banner year for her career, as we are reminded in this column from the Newspaper Enterprise Association, Aug. 25, 1977.

Actress Audra Lindley— A Hit Could Ruin Her Record

By DICK KLEINER

HOLLYWOOD — Audra Lindley could be in the Guinness Book of TV Records as the only lady who has been in three TV series on three different networks in one year — and they were all dropped.

But there's a problem. The last of the three shows is being brought back, that could spoil the whole thing.

Audra was part of the cast of NBC's Fay and CBS' Doc — without question, flops, at least judged from the standpoint of doing a quick fold. And then she began playing the wife of landlord Norman Fell on ABC's Three's Company.

That lasted six weeks earlier this spring. And that was that. Except the show astounded people, even ABC, by being in the top ten on four of those six weeks. So ABC, no slouch at recognizing a potential hit, is bringing it back. Audra says she has been told they'll make 22 more for next season, with an option for a few more after that.

ABC is going to pair it with a new show called Soap on Tuesday nights. Both of them are shows that are built on foundations of double entendres, so the network's obvious gambit is to make that Tuesday night slot a mild adventure in the risqué.

That's OK with Audra Lindley, who feels that it's far better to go in that direction than in the violent direction.

"I don't think Three's Company is sexy," she says. "There is certainly nothing lewd about it. It's just light and frothy and it has a very happy mood about it. It's like a slightly risque joke. Anyhow, I'd much rather there was sex than violence on TV."

"I don't think Three's Company is sexy," she says. "There is certainly nothing lewd about it. It's just light and frothy and it has a very happy mood about it. It's like a slightly risque joke. Anyhow, I'd much rather there was sex than violence on TV."

Audra Lindley isn't exactly what you'd call an old-time TV fan. In fact, for many years, there wasn't a TV set in her household. That's when her five children were small, and she felt TV was bad for them.

Then when she got divorced, somehow a TV set became a symbol of revolt, a gesture of defiance, so she went out and bought one.

But she still wasn't a big fan. In fact, a few years after that first set entered her life, she was signed to do a play with James Whitmore. She says she knew him by reputation, but she had never seen him work.

"The play was a hunk of junk," she says.

But things worked out. Audra became Mrs. James Whitmore in 1971. Until that time, she had always called New York home, even though she had been born and raised in California. But she grew up deciding to be a stage actress and went to New York and stayed the through thick and thin, mostly thick.

But Whitmore doesn't like New York. He much prefers California. So Audra came to California with him and, being a woman who loves working, started looking for work. She was lucky and found it — she played the part of Bridget's mother on Bridget Loves Bernie. She says that series was spoiled when the producers got away from the original concept.

At the moment she's very high on Three's Company. She likes her part and the people she's working with and the prospects for the project.

Audra's childhood was a moving one. Her father was an actor. Her mother was an actress who gave up her career when she had the fourth of her five children.

"My father wasn't very successful as an actor," she says. "Once in a while, now, I'll see him on a late, late show — he played a trapper with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy in 'Indian Love Call,' and that's on once in a while. "He kept moving every year selling a house and buying a new one, I guess he felt the new house would bring good luck, When he was 65, he became a make-up man and made more money than he ever made as an actor.

"But I think my mother lived vicariously in my career, because she'd given up her own. She helped me pack my bags when I went to New York."

Three’s Company lasted eight seasons, but Lindley and Fell were gone after only two years, given their own series. The Ropers died after 28 episodes. Reporter Kleiner caught up with Lindley afterward. In his column of July 15, 1981, she bluntly said the series was deliberately scuttled by ABC because someone at the network didn’t like it, and kept moving it around on the schedule every time it gained an audience.

She told Kleiner she didn’t want to go back to Three’s Company. Not that the show needed her. Don Knotts had been brought in to replace her and Fell, and the former Barney Fife was, as you might expect, a hit with viewers.

Her career didn’t end. She continued to work in theatre and television, appearing on as Cybill Shepherd’s mother on Cybill, taping an episode a month before she passed away in October 1997.

One of Lindley’s most interesting projects was a film distributed by B’Nai Brith in 1958. It was the tale of a teenage girl shunned by her friends and neighbours for her visible support of Jews. Patty Duke has a small role as a friend in this non-commercial film. You can see it below. This is far from the broad comedy of Mrs. Roper (this version of the print has no credits but was the cast was mentioned in various publications at the time).

We should qualify this. It was in a TV role she couldn’t get sex. And the show aired a little more than 35 years after this picture was taken.

She made her motion picture debut in 1941 opposite Ronnie Reagan in Warner Bros.’ The Flight Patrol, but was on the New York stage by the end of the year. You know her best as Mrs. Roper.

Three’s Company was Audra Lindley’s biggest success and led to a spin-off series starring her and TV husband Norman Fell. It debuted in 1977, which proved to be a busy and not altogether banner year for her career, as we are reminded in this column from the Newspaper Enterprise Association, Aug. 25, 1977.

Actress Audra Lindley— A Hit Could Ruin Her Record

By DICK KLEINER

HOLLYWOOD — Audra Lindley could be in the Guinness Book of TV Records as the only lady who has been in three TV series on three different networks in one year — and they were all dropped.

But there's a problem. The last of the three shows is being brought back, that could spoil the whole thing.

Audra was part of the cast of NBC's Fay and CBS' Doc — without question, flops, at least judged from the standpoint of doing a quick fold. And then she began playing the wife of landlord Norman Fell on ABC's Three's Company.

That lasted six weeks earlier this spring. And that was that. Except the show astounded people, even ABC, by being in the top ten on four of those six weeks. So ABC, no slouch at recognizing a potential hit, is bringing it back. Audra says she has been told they'll make 22 more for next season, with an option for a few more after that.

ABC is going to pair it with a new show called Soap on Tuesday nights. Both of them are shows that are built on foundations of double entendres, so the network's obvious gambit is to make that Tuesday night slot a mild adventure in the risqué.

That's OK with Audra Lindley, who feels that it's far better to go in that direction than in the violent direction.

"I don't think Three's Company is sexy," she says. "There is certainly nothing lewd about it. It's just light and frothy and it has a very happy mood about it. It's like a slightly risque joke. Anyhow, I'd much rather there was sex than violence on TV."

"I don't think Three's Company is sexy," she says. "There is certainly nothing lewd about it. It's just light and frothy and it has a very happy mood about it. It's like a slightly risque joke. Anyhow, I'd much rather there was sex than violence on TV."Audra Lindley isn't exactly what you'd call an old-time TV fan. In fact, for many years, there wasn't a TV set in her household. That's when her five children were small, and she felt TV was bad for them.

Then when she got divorced, somehow a TV set became a symbol of revolt, a gesture of defiance, so she went out and bought one.

But she still wasn't a big fan. In fact, a few years after that first set entered her life, she was signed to do a play with James Whitmore. She says she knew him by reputation, but she had never seen him work.

"The play was a hunk of junk," she says.

But things worked out. Audra became Mrs. James Whitmore in 1971. Until that time, she had always called New York home, even though she had been born and raised in California. But she grew up deciding to be a stage actress and went to New York and stayed the through thick and thin, mostly thick.

But Whitmore doesn't like New York. He much prefers California. So Audra came to California with him and, being a woman who loves working, started looking for work. She was lucky and found it — she played the part of Bridget's mother on Bridget Loves Bernie. She says that series was spoiled when the producers got away from the original concept.

At the moment she's very high on Three's Company. She likes her part and the people she's working with and the prospects for the project.

Audra's childhood was a moving one. Her father was an actor. Her mother was an actress who gave up her career when she had the fourth of her five children.

"My father wasn't very successful as an actor," she says. "Once in a while, now, I'll see him on a late, late show — he played a trapper with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy in 'Indian Love Call,' and that's on once in a while. "He kept moving every year selling a house and buying a new one, I guess he felt the new house would bring good luck, When he was 65, he became a make-up man and made more money than he ever made as an actor.

"But I think my mother lived vicariously in my career, because she'd given up her own. She helped me pack my bags when I went to New York."

Three’s Company lasted eight seasons, but Lindley and Fell were gone after only two years, given their own series. The Ropers died after 28 episodes. Reporter Kleiner caught up with Lindley afterward. In his column of July 15, 1981, she bluntly said the series was deliberately scuttled by ABC because someone at the network didn’t like it, and kept moving it around on the schedule every time it gained an audience.

She told Kleiner she didn’t want to go back to Three’s Company. Not that the show needed her. Don Knotts had been brought in to replace her and Fell, and the former Barney Fife was, as you might expect, a hit with viewers.

Her career didn’t end. She continued to work in theatre and television, appearing on as Cybill Shepherd’s mother on Cybill, taping an episode a month before she passed away in October 1997.

One of Lindley’s most interesting projects was a film distributed by B’Nai Brith in 1958. It was the tale of a teenage girl shunned by her friends and neighbours for her visible support of Jews. Patty Duke has a small role as a friend in this non-commercial film. You can see it below. This is far from the broad comedy of Mrs. Roper (this version of the print has no credits but was the cast was mentioned in various publications at the time).

Tuesday, 7 February 2023

Calling Tom and Jerry

A phone comes to life in the Van Beuren cartoon Hook and Ladder Hokum (1933). It whistles to firemen Tom and Jerry to get out of bed.

Unlike Flip the Frog’s phone in the 1930 Ub Iwerks cartoon The Cuckoo Murder Mystery, it doesn’t say “Damn!” or anything else.

There are several other gags I like here, such as the fire pole made from a stream of tap-water, and the flames coming from a house spelling “Help” and “Hurry.”

George Stallings and Frank Tashlin get the “by” credit.

Gene Rodemich’s score opens with “Rhythm,” which is heard through a good portion of the fire scene, along with “Corn-Fed Cal” and “The Streets of Cairo” (during the hose-charmer scene). Hear “Rhythm” below.

Unlike Flip the Frog’s phone in the 1930 Ub Iwerks cartoon The Cuckoo Murder Mystery, it doesn’t say “Damn!” or anything else.

There are several other gags I like here, such as the fire pole made from a stream of tap-water, and the flames coming from a house spelling “Help” and “Hurry.”

George Stallings and Frank Tashlin get the “by” credit.

Gene Rodemich’s score opens with “Rhythm,” which is heard through a good portion of the fire scene, along with “Corn-Fed Cal” and “The Streets of Cairo” (during the hose-charmer scene). Hear “Rhythm” below.

Labels:

Van Beuren

Monday, 6 February 2023

Coyly Hidden Gags

There were all kinds of people who didn’t get screen credit in Warner Bros. cartoons but, every once in a while, their names appeared on screen anyway.

Several cartoons involved characters or things on book covers coming to life. One was Bob Clampett’s A Coy Decoy (1941). These book cartoons featured books resting on shelves, and the name of a Leon Schlesinger employee might find his/her name inscribed on a cover or spine.

On the book to the right of Daffy you’ll see the name “Kirsanoff.” This was assistant animator Anatole Kirsanoff, born in Ukraine in 1911. His mother was Russian actress Maria Kirsanova. Kirsanoff attended the School of Applied Arts at the University of Cincinnati, where he received three first and three second place ribbons in an art competition in his senior year in 1935. In 1937, he was working for Walt Disney. His wife was opera singer Rosalia Lynn.

A check of some local newspapers reveals he moved from Schlesinger to the Walter Lantz studio by October 1941, he and two others opened a glass business in Los Angeles in 1947, and he was in Chicago in 1953. You might have seen his name on various Filmation series. Scouts will be interested to know he was involved with Cub Scout Pack 352 sponsored by the Coldwater Canyon Elementary School. Kirsanoff died on May 2, 1973, age 61.

The book behind Daffy is “The Downfall of the House of Sasanoff” by Thomas. Michael Sasanoff handled some story and layout work after Clampett took over Tex Avery’s unit in 1941. Sasanoff was Russian-born in 1903 to artist/singer Max Sasanoff and came to the U.S. in September 1913. He attended the National Academy of Design, the Art Students League and painted murals for various libraries, theatres and schools in New York. In 1928, he was involved in the New York Council of the Unemployed, which the New York Times described as "a Communist organization." 1938 saw him employed as an artist and spieler on Coney Island. The following year, Sasanoff was working for the Fleischers in Miami and legally changed his name from Mische to Michael, though he had been going by "Murray."

After his stint with Schlesinger, he found work in New York as TV creative director of the Biow Co. In 1948, he created Sunny the Rooster, produced by Telefilm and voiced by Hans Conried for Schenley. After stops at Sarra, Inc. (1949) and N.W. Ayer (1957), he worked as creative director from 1958-62 at Lawrence C. Gumbinner Advertising (animated spots for Roi-Tan Cigars and Omega Oil). Following that, he became a stockholder and creative vice-president of Henry R. Turnbull, Inc. At the time he was living in New Canaan, Conn., where he began directing operas in 1957 and exhibiting his (non-cartoon) artwork. He died Dec. 20, 1984.

“Thomas,” I suspect, is Dick Thomas, who supplied backgrounds for Clampett’s black-and-white unit. We profiled him in this post on the Yowp blog.

Norm McCabe is the credited animator in this short, while Mel Millar gets the story credit. It was released on June 7, 1941, and on that date it was screened at Warners’ Sigma Theatre in Lima, Ohio, with the Priscilla Lane feature Million Dollar Baby.

Several cartoons involved characters or things on book covers coming to life. One was Bob Clampett’s A Coy Decoy (1941). These book cartoons featured books resting on shelves, and the name of a Leon Schlesinger employee might find his/her name inscribed on a cover or spine.

On the book to the right of Daffy you’ll see the name “Kirsanoff.” This was assistant animator Anatole Kirsanoff, born in Ukraine in 1911. His mother was Russian actress Maria Kirsanova. Kirsanoff attended the School of Applied Arts at the University of Cincinnati, where he received three first and three second place ribbons in an art competition in his senior year in 1935. In 1937, he was working for Walt Disney. His wife was opera singer Rosalia Lynn.

A check of some local newspapers reveals he moved from Schlesinger to the Walter Lantz studio by October 1941, he and two others opened a glass business in Los Angeles in 1947, and he was in Chicago in 1953. You might have seen his name on various Filmation series. Scouts will be interested to know he was involved with Cub Scout Pack 352 sponsored by the Coldwater Canyon Elementary School. Kirsanoff died on May 2, 1973, age 61.

The book behind Daffy is “The Downfall of the House of Sasanoff” by Thomas. Michael Sasanoff handled some story and layout work after Clampett took over Tex Avery’s unit in 1941. Sasanoff was Russian-born in 1903 to artist/singer Max Sasanoff and came to the U.S. in September 1913. He attended the National Academy of Design, the Art Students League and painted murals for various libraries, theatres and schools in New York. In 1928, he was involved in the New York Council of the Unemployed, which the New York Times described as "a Communist organization." 1938 saw him employed as an artist and spieler on Coney Island. The following year, Sasanoff was working for the Fleischers in Miami and legally changed his name from Mische to Michael, though he had been going by "Murray."

After his stint with Schlesinger, he found work in New York as TV creative director of the Biow Co. In 1948, he created Sunny the Rooster, produced by Telefilm and voiced by Hans Conried for Schenley. After stops at Sarra, Inc. (1949) and N.W. Ayer (1957), he worked as creative director from 1958-62 at Lawrence C. Gumbinner Advertising (animated spots for Roi-Tan Cigars and Omega Oil). Following that, he became a stockholder and creative vice-president of Henry R. Turnbull, Inc. At the time he was living in New Canaan, Conn., where he began directing operas in 1957 and exhibiting his (non-cartoon) artwork. He died Dec. 20, 1984.

“Thomas,” I suspect, is Dick Thomas, who supplied backgrounds for Clampett’s black-and-white unit. We profiled him in this post on the Yowp blog.

Norm McCabe is the credited animator in this short, while Mel Millar gets the story credit. It was released on June 7, 1941, and on that date it was screened at Warners’ Sigma Theatre in Lima, Ohio, with the Priscilla Lane feature Million Dollar Baby.

Labels:

Bob Clampett,

Warner Bros.

Sunday, 5 February 2023

I Never Ate Jell-O

Out of curiosity, I did a newspaper search of this date 50 years ago to see what Jack Benny was up to. Lo and behold, there was a feature article about him in the Burlington (N.C.) Times-News.

This article had been released to subscribing papers by the North American Newspaper Alliance earlier. In those pre-internet days, it was not uncommon for feature pieces to be spiked (that is, put on hold; I worked in a newsroom decades ago that still used spikes on the wall for wire copy).

This version was published in the Bergen County Record, January 18. 1973

The story answers a question some Benny fans ask now and again—did Jack use his sponsors’ products? In the case of his two best-known sponsors, the answer is “no.”

The jokes were on Jack

By DAN LEWIS

Entertainment Columnist

HOLLYWOOD — Jack Benny was guest of honor at a party tossed by NBC and the parent RCA corporation the other night. As one would suspect, it was filled with great fun and nostalgia. What makes a Benny function fun-filled is that Jack not only likes to tell stories about himself, but enjoys repeating what others have said about him.

It was of course more than coincidence that the tribute should be paid to Benny on the eve of his first television special of the season, “The First Jack Benny Farewell Special” (tonight on NBC-TV, 9-10).

Probably the greatest tribute to Benny was reflected in the presence at the party of Bob Sarnoff, chairman of the RCA board and its chief operating officer, Julian Goodman, president of NBC, and Don Durgen, president of NBC-TV.

Jack was presented with a special gift, an old RCA radio set, 1929 vintage. When he flicked the dial, memories flooded the room, as the voice of the late Fred Allen boomed from its speaker via playbacks from his old radio show.

In the acid style that characterized their hilarious feud in radio's golden days, Allen was heard declaring: "Benny was born ignorant, and has been going down ever since." And. "Benny has a pig on stage so it can eat the things the audience throws at him. Some weeks he has two pigs."

Jack stood on stage listening and laughing hard. Then he recalled another Allen gag. "They planted trees in my honor in my home town of Waukegan, Ill.,” Jack recalled. “Allen said 'How can they expect the trees to grow in Waukegan when the sap is in Hollywood?' " Jack loved telling the story.

Jack also made some startling observations: "All the time I was so successful with Jell-o (as his sponsor) I never ate a drop of it. I hated Jell-o.”

Later, Jack's sponsor became Lucky Strike cigarettes. "I never smoked in my life," Jack declared.

The stories about Benny's alleged cheapness have been legendary. Jack does nothing to discourage them. Even at this party, he helped perpetuate the legend.

He revealed that while he was sitting at the table with Bob Sarnoff during the dinner, he said he wanted to show Sarnoff that all the stories about him were untrue.

"You know, Bob," Jack recalled telling Sarnoff. "I'm not cheap, I'd like to pay for this dinner here tonight.”

Sarnoff protested. Jack persisted.

Finally, Sarnoff told Benny, “No Jack, I’d feel better if you let me pay for it.”

“Well, Bob,” Jack responded, “if you’re [sic] health is involved. . .all right.”

40 TV critics were invited to the dinner. It appears the Chicago Tribune’s Clarence Petersen was one as he reported on it, and had more quotes from Jack:

"When it comes to commercials, people will remember what you said when they are laughing at the same time. I'll never forget the first time we did it. I was nearly thrown off the air.

"Because the first company I ever worked for was Canada Dry Ginger Ale. We had one that I thought was so funny, where I told the listening audience . . . that the product was so good that we had a salesman whose territory was the Sahara Desert, and this salesman ran into a caravan of about 30 people who were dying of thirst; so our salesman gave each of them a glass of Canada Dry Ginger Ale, and not one of them said it was a bad drink.

"Now that's funny, isn't it? And do you know I was nearly thrown off of that show. They were gonna say: 'How dare you? We can't have that kind of negative advertising!' ”

Among the guests was Jack’s long-time friend, George Burns. Petersen recounted:

From the sidelines, George Burns ventured onto thin ice by recalling one of Benny's earliest stingy jokes.

"YOU DID A JOKE about taking a girl to a cafeteria," said Burns, "and you said she laughed so loud she pretty near dropped her tray."

Benny stared for a moment, then exploded: "You just spoiled the joke! Now, I want to show you how a great comedian ... I want to show you how you spoiled that joke. I remember that joke. Now here's the way you tell it: 'I took my girl to a restaurant and I told her something and she laughed so hard that she dropped her tray.' That's funny. You immediately spoiled it by saying I took her to a cafeteria—well, for crissake, in a cafeteria she would have a tray. You ought to be ashamed of yourself!."

It was one of the few times Benny has got the best of Burns, but Benny also told of a more typical exchange:

"NOT LONG AGO THE FRIARS Club of New York gave a dinner for George and me ... so we go to New York, to the Plaza Hotel, and take a suite of rooms—a living room and two bedrooms, a bedroom for him and a bedroom for me.

"Now, I said: 'George, let's get to bed early tonight because tomorrow we've got to think, and we've got to work tomorrow night. It's a dinner for us, and we're both going to have to make speeches, so let's get to bed early.'

"So I go to bed. I want to show you what this man can do. It's unbelievable.

"About 3:30 or 4 o'clock in the morning, I feel something tugging at my arm, and I wake up, and it's George, standing there with a deck of cards in his hand and I can hardly open my eyes. I'm sound asleep and he is standing there and be says, 'take a card.'

"So like a damn fool, I took a card. And he says to me, look at it.'

"I can hardly see. So I looked at it and he said, 'put it back in the deck.'

"And I, like a fool, I put it back in the deck, and he says, 'thank you' and went back to his own bedroom. "I didn't sleep for the rest of the night."

And no one slept at the Jack Benny party either. Benny even played the violin for us, which was enough to sour the wine in your glass, but it left a very good taste in your mouth.

Sad to say, Benny’s first farewell special was just about his last. He planned a series of them and work had begun on the third when he died of pancreatic cancer just after Christmas in 1974.

This article had been released to subscribing papers by the North American Newspaper Alliance earlier. In those pre-internet days, it was not uncommon for feature pieces to be spiked (that is, put on hold; I worked in a newsroom decades ago that still used spikes on the wall for wire copy).

This version was published in the Bergen County Record, January 18. 1973

The story answers a question some Benny fans ask now and again—did Jack use his sponsors’ products? In the case of his two best-known sponsors, the answer is “no.”

The jokes were on Jack

By DAN LEWIS

Entertainment Columnist

HOLLYWOOD — Jack Benny was guest of honor at a party tossed by NBC and the parent RCA corporation the other night. As one would suspect, it was filled with great fun and nostalgia. What makes a Benny function fun-filled is that Jack not only likes to tell stories about himself, but enjoys repeating what others have said about him.

It was of course more than coincidence that the tribute should be paid to Benny on the eve of his first television special of the season, “The First Jack Benny Farewell Special” (tonight on NBC-TV, 9-10).

Probably the greatest tribute to Benny was reflected in the presence at the party of Bob Sarnoff, chairman of the RCA board and its chief operating officer, Julian Goodman, president of NBC, and Don Durgen, president of NBC-TV.

Jack was presented with a special gift, an old RCA radio set, 1929 vintage. When he flicked the dial, memories flooded the room, as the voice of the late Fred Allen boomed from its speaker via playbacks from his old radio show.

In the acid style that characterized their hilarious feud in radio's golden days, Allen was heard declaring: "Benny was born ignorant, and has been going down ever since." And. "Benny has a pig on stage so it can eat the things the audience throws at him. Some weeks he has two pigs."

Jack stood on stage listening and laughing hard. Then he recalled another Allen gag. "They planted trees in my honor in my home town of Waukegan, Ill.,” Jack recalled. “Allen said 'How can they expect the trees to grow in Waukegan when the sap is in Hollywood?' " Jack loved telling the story.

Jack also made some startling observations: "All the time I was so successful with Jell-o (as his sponsor) I never ate a drop of it. I hated Jell-o.”

Later, Jack's sponsor became Lucky Strike cigarettes. "I never smoked in my life," Jack declared.

The stories about Benny's alleged cheapness have been legendary. Jack does nothing to discourage them. Even at this party, he helped perpetuate the legend.

He revealed that while he was sitting at the table with Bob Sarnoff during the dinner, he said he wanted to show Sarnoff that all the stories about him were untrue.

"You know, Bob," Jack recalled telling Sarnoff. "I'm not cheap, I'd like to pay for this dinner here tonight.”

Sarnoff protested. Jack persisted.

Finally, Sarnoff told Benny, “No Jack, I’d feel better if you let me pay for it.”

“Well, Bob,” Jack responded, “if you’re [sic] health is involved. . .all right.”

40 TV critics were invited to the dinner. It appears the Chicago Tribune’s Clarence Petersen was one as he reported on it, and had more quotes from Jack:

"When it comes to commercials, people will remember what you said when they are laughing at the same time. I'll never forget the first time we did it. I was nearly thrown off the air.

"Because the first company I ever worked for was Canada Dry Ginger Ale. We had one that I thought was so funny, where I told the listening audience . . . that the product was so good that we had a salesman whose territory was the Sahara Desert, and this salesman ran into a caravan of about 30 people who were dying of thirst; so our salesman gave each of them a glass of Canada Dry Ginger Ale, and not one of them said it was a bad drink.

"Now that's funny, isn't it? And do you know I was nearly thrown off of that show. They were gonna say: 'How dare you? We can't have that kind of negative advertising!' ”

Among the guests was Jack’s long-time friend, George Burns. Petersen recounted:

From the sidelines, George Burns ventured onto thin ice by recalling one of Benny's earliest stingy jokes.

"YOU DID A JOKE about taking a girl to a cafeteria," said Burns, "and you said she laughed so loud she pretty near dropped her tray."

Benny stared for a moment, then exploded: "You just spoiled the joke! Now, I want to show you how a great comedian ... I want to show you how you spoiled that joke. I remember that joke. Now here's the way you tell it: 'I took my girl to a restaurant and I told her something and she laughed so hard that she dropped her tray.' That's funny. You immediately spoiled it by saying I took her to a cafeteria—well, for crissake, in a cafeteria she would have a tray. You ought to be ashamed of yourself!."

It was one of the few times Benny has got the best of Burns, but Benny also told of a more typical exchange:

"NOT LONG AGO THE FRIARS Club of New York gave a dinner for George and me ... so we go to New York, to the Plaza Hotel, and take a suite of rooms—a living room and two bedrooms, a bedroom for him and a bedroom for me.

"Now, I said: 'George, let's get to bed early tonight because tomorrow we've got to think, and we've got to work tomorrow night. It's a dinner for us, and we're both going to have to make speeches, so let's get to bed early.'

"So I go to bed. I want to show you what this man can do. It's unbelievable.

"About 3:30 or 4 o'clock in the morning, I feel something tugging at my arm, and I wake up, and it's George, standing there with a deck of cards in his hand and I can hardly open my eyes. I'm sound asleep and he is standing there and be says, 'take a card.'

"So like a damn fool, I took a card. And he says to me, look at it.'

"I can hardly see. So I looked at it and he said, 'put it back in the deck.'

"And I, like a fool, I put it back in the deck, and he says, 'thank you' and went back to his own bedroom. "I didn't sleep for the rest of the night."

And no one slept at the Jack Benny party either. Benny even played the violin for us, which was enough to sour the wine in your glass, but it left a very good taste in your mouth.

Sad to say, Benny’s first farewell special was just about his last. He planned a series of them and work had begun on the third when he died of pancreatic cancer just after Christmas in 1974.

Labels:

Fred Allen,

Jack Benny

Saturday, 4 February 2023

The Pride of Portis

Mike Maltese doesn’t have a marker celebrating his life. Neither do Warren Foster or Tedd Pierce. But one Warner Bros. cartoon writer does.

At the corner of Market and East 5th streets in Portis, Kansas, you’ll find a long wooden marker in a little park in memory of Mel Millar, known as Tubby in his time at the cartoon studio.

Millar worked on animated shorts for various directors into the 1940s when he left the studio and began a career as a freelance print cartoonist. He’s even caricatured in Tex Avery’s 1936 cartoon Page Miss Glory. Millar lived in Burbank much of his life and was deemed enough of a celebrity to be profiled in area newspapers.

First is this piece from the Van Nuys News of May 5, 1949. The above self-portrait is from part of an ad announcing Tubby's hiring in 1949.

‘Little Slocum’, Other Cartoons By Mel Millar Slated for ‘News’

There’s a new little youngster coming to Van Nuys—a perky, happy little fellow in a big sombrero, and you're going to see a lot of this happy chappy in the weeks to come, because he is going to be here and there and ‘round-about in the Valley to greet all present residents and newcomers.

His name? “Little Slocum”!

He is a pen-child created by Mel Millar, nationally known cartoonist and illustrator, and has been devised by Millar to tell the thousands of Valley residents about Slocum Furniture Co. at 6187 Van Nuys Blvd., and of the wide selection of home furnishings to be found there at attractive prices.

He is a pen-child created by Mel Millar, nationally known cartoonist and illustrator, and has been devised by Millar to tell the thousands of Valley residents about Slocum Furniture Co. at 6187 Van Nuys Blvd., and of the wide selection of home furnishings to be found there at attractive prices.

Pictures Each Issue

Little Slocum’s pen-master is a Valley man himself, and everyone has seen his clever, laugh-provoking cartoons in such leading newspapers and magazines as The New York Times, Collier’s, and many others.

Now readers of The News will see Millar’s famous drawings in each issue of this newspaper, and will enjoy them thoroughly, as they will enjoy Little Slocum’s periodic appearances in these pages to act as an alter ego to the cartoons, and to carry the Slocum Furniture message to the public.

As for Mel Millar, he has led an interesting and varied life. Born in the Sunflower State at the turn of the century, he began his artistic attempts on the side of a barn with a piece of rock.

Finishing high school, he served a short hitch in the Navy, then came out determined to pursue art as a career and specialized in cartooning at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.

Draws For The Best

From here Millar went into an agency, was with a film advertising firm, then came to Hollywood in 1931 and worked in animated cartoons at Warner Brothers.

In 1944 he returned to free lancing and since that time has drawn illustrations for Talking Komics, and has sold to Collier’s, This Week, Argosy, New York Times, King Features, Fortnight and others. Also had his own cartoon business in Pasadena for a couple of years, and taught at the Hollywood Art Center School.

“I have a theory that cartoons are the best attention getters, and I sincerely hope everyone will enjoy meeting up with Little Slocum as he greets you in these columns, and also will enjoy the creations I shall draw for publication in The News,” was Millar’s statement today in discussing this new series.

We jump ahead to December 28, 1967, when this was published in the Valley News.

Mel Millar’s Cartoons Span 3 Decades of Good Humor

By BETTY RADSTONE

Clever cartoonists make most of us feel merry the year around. One of the best-liked American cartoonists has lived and worked in Burbank for the past 32 years. He is Mel Millar who resides at 120 S. Beachwood Drive with his wife Helen and their two cats.

In some ways Mel looks and acts like some of the cartoon characters he draws. Five-foot-six in height and almost that dimension in girth, he lives his humor. When Mel explains a gag, he laughs and shakes — much as Santa Claus — like a bowlful of jelly. His favorite hobby is eating.

The 67-year-old cartoonist, who has created some 10,000 cartoons during his career, wanted to be a cartoonist since he was a boy. In particular, he wanted to be a political cartoonist.

Millar has worked at one of the largest animation studios in Hollywood, has written books on cartooning, and has had many of his cartoons published not only nationally but reproduced in publications throughout the world. One popular book he has written is a pocketbook, “How to Draw Cartoons.”

Millar is known not only as a magazine, trade journal, and advertising cartoonist, but as the cartoonist’s cartoonist. He receives mail regularly from aspiring young artists as well as from world-famous cartoonists.

Often, Millar receives letters asking, “would you please send me all you know about cartooning in the enclosed stamped envelope?” he said.

In 1920 Millar graduated from the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. This was just a few years after Walt Disney’s graduation from the school. In fact, for about a decade Millar seemed to follow Disney’s footsteps from school, to work in Kansas City, to California.

Millar worked for the United Film Ad Service in Kansas City, Mo., from 1927 until he came to California in 1931.

His first job in California was at Warner Bros., where he stayed until 1945. His duties at the studio included being a cartoonist, a gagwriter, and storyman.

During his employment at Warner Bros., he drew well-known cartoon characters such as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig.

Syndicate Work

Since 1945, Millar has set up shop in a studio in his Burbank home and has become a free lance cartoonist.

Since 1945, Millar has set up shop in a studio in his Burbank home and has become a free lance cartoonist.

His work has appeared consistently in leading publications across the United States. You can find his work in the Saturday Evening Post and his drawings also have been used by King Features and other syndications.

During the past several years his works have been published nationally in a quarterly advertising booklet called “Happy Days.”

Several years ago, Parade, a national Sunday supplement magazine, asked opinions of America’s leading comedians as to what cartoonist they thought the funniest.

Interpret Differently

The late Ed Wynn, dean of all comedians, picked Mel Millar. As a result, a page of Millar’s cartoons, selected by Wynn, was featured in Parade.

“No art school can make a cartoonist. They only teach one to draw,” Millar stated. He said cartoonists interpret differently than other artists and views cartooning as an art within an art.

“A cartoonist is an artist, but an artist is not necessarily a cartoonist,” Millar said.

“Artists reflect themselves, whereas cartoonists reflect the situation in a gentle satire,” he added.

Need Experience

As far as “what” makes the cartoonist, Millar said:

“It is the humor or satire of the idea that makes the cartoonist. And the originating of the ideas comes from observation and accumulated experiences of the various things one has seen or done.”

He said that cartoonists have an art of visualizing the humor in situations which many people miss until they actually see it in the cartoon.

The professional cartoonist must be versatile, refreshing understanding, and have a wide range of interests, according to Millar.

The 'Parade' cartoons appeared in papers April 27, 1958. One is to the right. You should be able to find them in a search of newspapers of the era.

The 'Parade' cartoons appeared in papers April 27, 1958. One is to the right. You should be able to find them in a search of newspapers of the era.

If you see a reference to Portis in the background of 1930s Warners cartoons, you will now know the man who is the subject.

Melvin Eugene Millar was 80 when he passed away on December 30, 1980.

At the corner of Market and East 5th streets in Portis, Kansas, you’ll find a long wooden marker in a little park in memory of Mel Millar, known as Tubby in his time at the cartoon studio.

Millar worked on animated shorts for various directors into the 1940s when he left the studio and began a career as a freelance print cartoonist. He’s even caricatured in Tex Avery’s 1936 cartoon Page Miss Glory. Millar lived in Burbank much of his life and was deemed enough of a celebrity to be profiled in area newspapers.

First is this piece from the Van Nuys News of May 5, 1949. The above self-portrait is from part of an ad announcing Tubby's hiring in 1949.

‘Little Slocum’, Other Cartoons By Mel Millar Slated for ‘News’

There’s a new little youngster coming to Van Nuys—a perky, happy little fellow in a big sombrero, and you're going to see a lot of this happy chappy in the weeks to come, because he is going to be here and there and ‘round-about in the Valley to greet all present residents and newcomers.

His name? “Little Slocum”!

He is a pen-child created by Mel Millar, nationally known cartoonist and illustrator, and has been devised by Millar to tell the thousands of Valley residents about Slocum Furniture Co. at 6187 Van Nuys Blvd., and of the wide selection of home furnishings to be found there at attractive prices.

He is a pen-child created by Mel Millar, nationally known cartoonist and illustrator, and has been devised by Millar to tell the thousands of Valley residents about Slocum Furniture Co. at 6187 Van Nuys Blvd., and of the wide selection of home furnishings to be found there at attractive prices.Pictures Each Issue

Little Slocum’s pen-master is a Valley man himself, and everyone has seen his clever, laugh-provoking cartoons in such leading newspapers and magazines as The New York Times, Collier’s, and many others.

Now readers of The News will see Millar’s famous drawings in each issue of this newspaper, and will enjoy them thoroughly, as they will enjoy Little Slocum’s periodic appearances in these pages to act as an alter ego to the cartoons, and to carry the Slocum Furniture message to the public.

As for Mel Millar, he has led an interesting and varied life. Born in the Sunflower State at the turn of the century, he began his artistic attempts on the side of a barn with a piece of rock.

Finishing high school, he served a short hitch in the Navy, then came out determined to pursue art as a career and specialized in cartooning at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.

Draws For The Best

From here Millar went into an agency, was with a film advertising firm, then came to Hollywood in 1931 and worked in animated cartoons at Warner Brothers.

In 1944 he returned to free lancing and since that time has drawn illustrations for Talking Komics, and has sold to Collier’s, This Week, Argosy, New York Times, King Features, Fortnight and others. Also had his own cartoon business in Pasadena for a couple of years, and taught at the Hollywood Art Center School.

“I have a theory that cartoons are the best attention getters, and I sincerely hope everyone will enjoy meeting up with Little Slocum as he greets you in these columns, and also will enjoy the creations I shall draw for publication in The News,” was Millar’s statement today in discussing this new series.

We jump ahead to December 28, 1967, when this was published in the Valley News.

Mel Millar’s Cartoons Span 3 Decades of Good Humor

By BETTY RADSTONE

Clever cartoonists make most of us feel merry the year around. One of the best-liked American cartoonists has lived and worked in Burbank for the past 32 years. He is Mel Millar who resides at 120 S. Beachwood Drive with his wife Helen and their two cats.

In some ways Mel looks and acts like some of the cartoon characters he draws. Five-foot-six in height and almost that dimension in girth, he lives his humor. When Mel explains a gag, he laughs and shakes — much as Santa Claus — like a bowlful of jelly. His favorite hobby is eating.

The 67-year-old cartoonist, who has created some 10,000 cartoons during his career, wanted to be a cartoonist since he was a boy. In particular, he wanted to be a political cartoonist.

Millar has worked at one of the largest animation studios in Hollywood, has written books on cartooning, and has had many of his cartoons published not only nationally but reproduced in publications throughout the world. One popular book he has written is a pocketbook, “How to Draw Cartoons.”

Millar is known not only as a magazine, trade journal, and advertising cartoonist, but as the cartoonist’s cartoonist. He receives mail regularly from aspiring young artists as well as from world-famous cartoonists.

Often, Millar receives letters asking, “would you please send me all you know about cartooning in the enclosed stamped envelope?” he said.

In 1920 Millar graduated from the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. This was just a few years after Walt Disney’s graduation from the school. In fact, for about a decade Millar seemed to follow Disney’s footsteps from school, to work in Kansas City, to California.

Millar worked for the United Film Ad Service in Kansas City, Mo., from 1927 until he came to California in 1931.

His first job in California was at Warner Bros., where he stayed until 1945. His duties at the studio included being a cartoonist, a gagwriter, and storyman.

During his employment at Warner Bros., he drew well-known cartoon characters such as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig.

Syndicate Work

Since 1945, Millar has set up shop in a studio in his Burbank home and has become a free lance cartoonist.

Since 1945, Millar has set up shop in a studio in his Burbank home and has become a free lance cartoonist.His work has appeared consistently in leading publications across the United States. You can find his work in the Saturday Evening Post and his drawings also have been used by King Features and other syndications.

During the past several years his works have been published nationally in a quarterly advertising booklet called “Happy Days.”

Several years ago, Parade, a national Sunday supplement magazine, asked opinions of America’s leading comedians as to what cartoonist they thought the funniest.

Interpret Differently

The late Ed Wynn, dean of all comedians, picked Mel Millar. As a result, a page of Millar’s cartoons, selected by Wynn, was featured in Parade.

“No art school can make a cartoonist. They only teach one to draw,” Millar stated. He said cartoonists interpret differently than other artists and views cartooning as an art within an art.

“A cartoonist is an artist, but an artist is not necessarily a cartoonist,” Millar said.

“Artists reflect themselves, whereas cartoonists reflect the situation in a gentle satire,” he added.

Need Experience

As far as “what” makes the cartoonist, Millar said:

“It is the humor or satire of the idea that makes the cartoonist. And the originating of the ideas comes from observation and accumulated experiences of the various things one has seen or done.”

He said that cartoonists have an art of visualizing the humor in situations which many people miss until they actually see it in the cartoon.

The professional cartoonist must be versatile, refreshing understanding, and have a wide range of interests, according to Millar.

The 'Parade' cartoons appeared in papers April 27, 1958. One is to the right. You should be able to find them in a search of newspapers of the era.

The 'Parade' cartoons appeared in papers April 27, 1958. One is to the right. You should be able to find them in a search of newspapers of the era.

If you see a reference to Portis in the background of 1930s Warners cartoons, you will now know the man who is the subject.

Melvin Eugene Millar was 80 when he passed away on December 30, 1980.

Labels:

Warner Bros.

Friday, 3 February 2023

Mommy, Where Does Jippo Come From?

A singing Bimbo (accompanied by a ukulele), Ko Ko and Betty Boop rake in profits from their new wonder tonic Jippo.

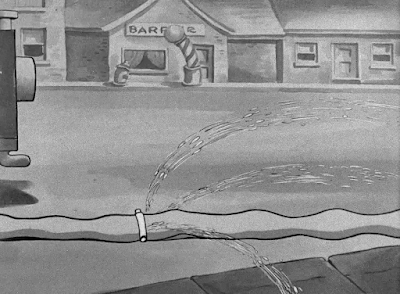

Where does Jippo come from? We start with a guy bottling it from a barrel. But let’s follow the trail.

The fire hydrant is a classy one. It wipes off its own mouth.

The fact that Jippo is plain, old water doesn’t make sense in light of its effects on people, but that’s just spoiling things. With a Fleischer cartoon of this era (1932), it’s best to get caught up in the absurdities, role reversals, and instant life by inanimate objects that made the studio’s cartoons the most entertaining of the first half of the ‘30s.

Willard Bowsky and Tom Goodson are the credited animators.

Where does Jippo come from? We start with a guy bottling it from a barrel. But let’s follow the trail.

The fire hydrant is a classy one. It wipes off its own mouth.

The fact that Jippo is plain, old water doesn’t make sense in light of its effects on people, but that’s just spoiling things. With a Fleischer cartoon of this era (1932), it’s best to get caught up in the absurdities, role reversals, and instant life by inanimate objects that made the studio’s cartoons the most entertaining of the first half of the ‘30s.

Willard Bowsky and Tom Goodson are the credited animators.

Labels:

Fleischer

Thursday, 2 February 2023

Buddies Thicker Than Water

When Gene Deitch was handed the task of creating new Tom and Jerry cartoons for MGM, he and his writers put the cat and mouse in different locales. For a time they were paired with a grumpy guy who reminded speculating cartoon fans of Clint Clobber from Deitch’s Terrytoons (he wasn’t Clobber, as Deitch had to inform them).

However, in Buddies Thicker Than Water (released in 1962), Tom’s owned by a young lady in an urban penthouse apartment.

Having come from UPA where design was practically everything, Deitch and his artists came up with exaggerations on ultra-current home interiors.

This is a lovely satire on 1962 home interiors. Who had a pole lamp like that? We did. Or that plant? We did. Or that clock or divider or plastic chair? We didn’t, but I knew people who did. (The chair was the same colour, too).

The uncredited background artist came up with a different background to use as a close-up. Actually, this is part of a long background that was panned left-to-right at one point in the cartoon.

A view from the other direction.

This kitchen is pretty basic and dull. But at least Deitch (or whomever handled this kind of thing) has it laid out at an angle.

Dig the modern art portrait of Tom.

More modern art. My guess is a blue filter was placed over the camera.

The cartoon starts with some exteriors; I presume the setting is supposed to be Manhattan. The snow is on a couple of cycles. The penthouse has a jazzy human statue next to the tree and a crazy TV antenna on top.

Animation? Soundtrack? Well, let’s forget those for now and say the backgrounds in this short may be the most attractive thing about it.

However, in Buddies Thicker Than Water (released in 1962), Tom’s owned by a young lady in an urban penthouse apartment.

Having come from UPA where design was practically everything, Deitch and his artists came up with exaggerations on ultra-current home interiors.

This is a lovely satire on 1962 home interiors. Who had a pole lamp like that? We did. Or that plant? We did. Or that clock or divider or plastic chair? We didn’t, but I knew people who did. (The chair was the same colour, too).

The uncredited background artist came up with a different background to use as a close-up. Actually, this is part of a long background that was panned left-to-right at one point in the cartoon.

A view from the other direction.

This kitchen is pretty basic and dull. But at least Deitch (or whomever handled this kind of thing) has it laid out at an angle.

Dig the modern art portrait of Tom.

More modern art. My guess is a blue filter was placed over the camera.

The cartoon starts with some exteriors; I presume the setting is supposed to be Manhattan. The snow is on a couple of cycles. The penthouse has a jazzy human statue next to the tree and a crazy TV antenna on top.

Animation? Soundtrack? Well, let’s forget those for now and say the backgrounds in this short may be the most attractive thing about it.

Labels:

Gene Deitch,

MGM

Wednesday, 1 February 2023

The Long-Time Residents of Wistful Vista

If Fibber McGee and Molly consisted solely of an overcrowded closet gimmick, it never would have lasted almost 2½ decades.

The series featured ordinary people in ordinary situations that came across as completely plausible. Certainly listeners must have known an ill-informed braggart like McGee or a woman who put up with her husband’s foibles like Molly.

Jim and Marian Jordan don’t seem to have talked a lot about the show during its heyday. After WW2, the only newspaper articles I’ve found unvolve the Jordans, and the show’s timeline.

Here’s an example from the Tampa Tribune of April 17, 1949. It has a quote from Jim Jordan about the programme’s success.

STILL TOPS

Fibber McGee and Molly On Radio For 15 Years

Most of the radio stars you heard 15 years ago are gone, because that's a long, long time in this comparatively new entertainment medium.

The few who are still on the air include Marian and Jim Jordan who as Fibber McGee and Molly have steadily increased in popularity through the years. As they celebrate the start of their 15th year next Tuesday night over WFLA and WFLA-FM, The Tribune stations. Fibber and Molly stand in the number one spot as radio's most popular comedians.

Their steady rise in popularity is credited to strict adherence to what is known as "the Fibber McGee and Molly program formula."

"First on our list of ‘musts’ is kindness," explains McGee. "Beyond skirting such subjects as serious infirmities, races and religions, which simply is a matter of good taste and good judgment, we extend the taboo to any material which strives for laughs with nasty innuendo or acidulous comment. We can take and dish out insults, but if they are not intrinsically good natured, we don't want them."

Jim Jordan and Marian Driscoll met during choir practice in their home town, Peoria, Ill. He was 17, she was 16, and it was love at first sight. Several years passed and then, on Aug. 31, 1918, they were married. Five days later, Jim went to France for Army service in World War I.

Jim returned from overseas in the Summer of 1919 and the Jordans launched their theatrical career. Their act was a success and a long vaudeville tour followed. They toured until two months before their second child, Jim, Jr., was born in the Summer of 1923. Marian remained In Peoria and Jim tried it alone without luck. After six months, the two teamed up again, but their act failed to click and they went broke 50 miles from home.

After a series of odd jobs, Jim returned to Chicago and became the tenor part of a singing team. During a visit to his brother, the Jordans were listening to a radio broadcast when Jan [sic] declared, "we could do a better job of singing than anyone on that program."

"Ten dollars says you can't," answered his brother.

Thus, on a dare two shaky people started a history making radio career. After an audition, they were signed for a commercial show at $10 a broadcast once a week. A few years later they met Don Quinn, cartoonist turned radio writer. The combination turned out Smackout, a five-a-week serial, and their first network show.

Fourteen years ago, the Jordans made their debut as Fibber McGee and Molly, the Tuesday night program that has become an American institution.

The same paper, on Sept. 11, 1949, quoted Jordan further:

"To us, comedy is merely a risible distortion of circumstances and attitudes. Mostly, of course, a distortion by exaggeration, which we think is the American type of humor. And as for construction we simply take an ordinary humorous incident, dilly it up, broaden its scope, throw in a couple of non-sequiturs, hide the denouement behind a few inconsequentials, indicate a glass crash, and pay it all off with a word twist."

Few radio stars, it seems, reached such heights that the network cleared time for a special broadcast to honour them. Jack Benny was one in 1941 (though it seems some back-room sponsor politics might have been involved). And Jim and Marian Jordan were another.

This plug was one of a number. It was in Alice G. Stewart’s radio column in the Latrobe (Pa.) Bulletin, Sept. 13, 1949.

RADIO DOINGS

The greatest names in radio will help Fibber McGee and Molly celebrate their 15th anniversary on NBC in a special, hour-long program this evening at 9’clock.

Such "newcomers” as Bob Hope, Dennis Day, Phil Harris and Alice Faye and others will join an old Wistful Vista neighbour, Harold ("The Great Gildersleeve") Peary in paying tribute to a program and a comedy team which have made radio history.

The anniversary program will be written by Don Quinn, who has been head writer since Fibber and Molly started on the air, and Phil Leslie, who has been his assistant for the past five years. It will be produced by Frank Pittman, regular Fibber and Molly producer.

Jim and Marian Jordan started playing Fibber and Molly in 1935 and have since become so identified with their fictional counterparts that they are accustomed to being addressed as "Mr. and Mrs. McGee." Back in 1935, however, not too many people had heard of the Jordans, who were doing a program called "Smack-out” from NBC’s Chicago studios. Fortunately for them, one of the people who did hear and enjoy them was Jack Louis, vice president of Needham, Louis and Brorby, Inc., the advertising agency for Johnson's Wax. When the Johnson people decided to sponsor a new radio program, Louis remembered "Smackout," which was being written by Don Quinn. Out of many conferences involving the Jordan’s, Quinn, the agency and sponsor came Fibber McGee and Molly.

The public's reaction was slow at first—but not for long. The McGees steadily won public favor with their original situation comedy. By 1937 they had been called to Hollywood to make "This Way, Please" for Paramount. In 1938 they moved to their present Tuesday-night spot on NBC from the Monday time they had originally occupied. The ratings of the program at first by Crossely [sic] and in recent years by Hooper, have shown them to be the most consistently popular program on the air.

In their climb to success, the Jordans brought others with them. Don Quinn, of course, is one of the top writers in the radio business. Harold Peary, whose "You're a hard man, McGee," became a national byword has been the star of his own successful program "The Great Gildersleeve," since 1941. One year the McGees had a maid named Beulah, played by Marlin Hurt. Beulah, too, became a star and still is, despite the fact that Hurt, who created the role, has since died. Perry Como once sang during the pleasant musical interludes of the Fibber and Molly program, filled now by the King's Men and Billy Mills' orchestra. And the former drummer in the Mills band was none other than Spike Jones, now also a star In his own right.

In their climb to success, the Jordans brought others with them. Don Quinn, of course, is one of the top writers in the radio business. Harold Peary, whose "You're a hard man, McGee," became a national byword has been the star of his own successful program "The Great Gildersleeve," since 1941. One year the McGees had a maid named Beulah, played by Marlin Hurt. Beulah, too, became a star and still is, despite the fact that Hurt, who created the role, has since died. Perry Como once sang during the pleasant musical interludes of the Fibber and Molly program, filled now by the King's Men and Billy Mills' orchestra. And the former drummer in the Mills band was none other than Spike Jones, now also a star In his own right.

Announcer Harlow Wilcox started with the McGees when they first went on the air back in 1935 and is now one of the most sought-after announcers in radio. His reading of Don Qulnn's announcements is always the winner in polls of the most commercial. The other members of the cast—Bill Thompson as the Old Timer and Wallace Wimple, Arthur Q. Bryan as Doc Gamble, and Gale Gordon as Mayor LaTrivia—have earned places in the national consciousness and national heart second only to that large spot occupied by the McGees themselves.

Fibber McGee and Molly are as popular in sophisticated Hollywood as they are in the Jordan's home town, Peoria. The entire radio and motion picture colony turned out to honor them on the occasion of their 10th anniversary in 1944. The same stars will be on hand to wish them well on tonight when they begin their 15th year on the air.

The first show appeared on NBC on April 16, 1935 and moved from Monday to Tuesday on March 15, 1938. Johnson Wax of Racine, Wisconsin was the long-time sponsor through the ‘30s and ‘40s. But then television started siphoning off the advertising money that used to go into radio. Johnson dropped Fibber, who picked up some new sponsors. Soon, it was shed of its orchestra, studio audience, and some secondary supporting players, becoming a daily, transcribed, 15-minute show on NBC from 1953 to 1957. Harlow Wilcox was replaced by John Wald. After that, it was a shell of itself. Jim and Marian Jordan recorded some short dialogues for NBC’s “Monitor” programme before being shoved out the door. The Jordans avoided television; a Fibber and Molly TV show with Bob Sweeney and Cathy Lewis never found an audience.

Marion Jordan died in 1961. Jim followed in 1988.

Quinn looked at the show after its demise and stated that it was vague in a lot of areas on purpose. “We preferred to let the audience paint its own scenery,” he told wire service writer Bob Thomas. “It seems to me television doesn’t give enough credit to the audience’s I.Q.—imagination quotient.”

Imagination was not only what Fibber and Molly was about. It was the keystone behind old radio itself.

The series featured ordinary people in ordinary situations that came across as completely plausible. Certainly listeners must have known an ill-informed braggart like McGee or a woman who put up with her husband’s foibles like Molly.

Jim and Marian Jordan don’t seem to have talked a lot about the show during its heyday. After WW2, the only newspaper articles I’ve found unvolve the Jordans, and the show’s timeline.

Here’s an example from the Tampa Tribune of April 17, 1949. It has a quote from Jim Jordan about the programme’s success.

STILL TOPS

Fibber McGee and Molly On Radio For 15 Years

Most of the radio stars you heard 15 years ago are gone, because that's a long, long time in this comparatively new entertainment medium.

The few who are still on the air include Marian and Jim Jordan who as Fibber McGee and Molly have steadily increased in popularity through the years. As they celebrate the start of their 15th year next Tuesday night over WFLA and WFLA-FM, The Tribune stations. Fibber and Molly stand in the number one spot as radio's most popular comedians.

Their steady rise in popularity is credited to strict adherence to what is known as "the Fibber McGee and Molly program formula."

"First on our list of ‘musts’ is kindness," explains McGee. "Beyond skirting such subjects as serious infirmities, races and religions, which simply is a matter of good taste and good judgment, we extend the taboo to any material which strives for laughs with nasty innuendo or acidulous comment. We can take and dish out insults, but if they are not intrinsically good natured, we don't want them."

Jim Jordan and Marian Driscoll met during choir practice in their home town, Peoria, Ill. He was 17, she was 16, and it was love at first sight. Several years passed and then, on Aug. 31, 1918, they were married. Five days later, Jim went to France for Army service in World War I.

Jim returned from overseas in the Summer of 1919 and the Jordans launched their theatrical career. Their act was a success and a long vaudeville tour followed. They toured until two months before their second child, Jim, Jr., was born in the Summer of 1923. Marian remained In Peoria and Jim tried it alone without luck. After six months, the two teamed up again, but their act failed to click and they went broke 50 miles from home.

After a series of odd jobs, Jim returned to Chicago and became the tenor part of a singing team. During a visit to his brother, the Jordans were listening to a radio broadcast when Jan [sic] declared, "we could do a better job of singing than anyone on that program."

"Ten dollars says you can't," answered his brother.

Thus, on a dare two shaky people started a history making radio career. After an audition, they were signed for a commercial show at $10 a broadcast once a week. A few years later they met Don Quinn, cartoonist turned radio writer. The combination turned out Smackout, a five-a-week serial, and their first network show.

Fourteen years ago, the Jordans made their debut as Fibber McGee and Molly, the Tuesday night program that has become an American institution.

The same paper, on Sept. 11, 1949, quoted Jordan further:

"To us, comedy is merely a risible distortion of circumstances and attitudes. Mostly, of course, a distortion by exaggeration, which we think is the American type of humor. And as for construction we simply take an ordinary humorous incident, dilly it up, broaden its scope, throw in a couple of non-sequiturs, hide the denouement behind a few inconsequentials, indicate a glass crash, and pay it all off with a word twist."

Few radio stars, it seems, reached such heights that the network cleared time for a special broadcast to honour them. Jack Benny was one in 1941 (though it seems some back-room sponsor politics might have been involved). And Jim and Marian Jordan were another.

This plug was one of a number. It was in Alice G. Stewart’s radio column in the Latrobe (Pa.) Bulletin, Sept. 13, 1949.

RADIO DOINGS

The greatest names in radio will help Fibber McGee and Molly celebrate their 15th anniversary on NBC in a special, hour-long program this evening at 9’clock.

Such "newcomers” as Bob Hope, Dennis Day, Phil Harris and Alice Faye and others will join an old Wistful Vista neighbour, Harold ("The Great Gildersleeve") Peary in paying tribute to a program and a comedy team which have made radio history.

The anniversary program will be written by Don Quinn, who has been head writer since Fibber and Molly started on the air, and Phil Leslie, who has been his assistant for the past five years. It will be produced by Frank Pittman, regular Fibber and Molly producer.

Jim and Marian Jordan started playing Fibber and Molly in 1935 and have since become so identified with their fictional counterparts that they are accustomed to being addressed as "Mr. and Mrs. McGee." Back in 1935, however, not too many people had heard of the Jordans, who were doing a program called "Smack-out” from NBC’s Chicago studios. Fortunately for them, one of the people who did hear and enjoy them was Jack Louis, vice president of Needham, Louis and Brorby, Inc., the advertising agency for Johnson's Wax. When the Johnson people decided to sponsor a new radio program, Louis remembered "Smackout," which was being written by Don Quinn. Out of many conferences involving the Jordan’s, Quinn, the agency and sponsor came Fibber McGee and Molly.

The public's reaction was slow at first—but not for long. The McGees steadily won public favor with their original situation comedy. By 1937 they had been called to Hollywood to make "This Way, Please" for Paramount. In 1938 they moved to their present Tuesday-night spot on NBC from the Monday time they had originally occupied. The ratings of the program at first by Crossely [sic] and in recent years by Hooper, have shown them to be the most consistently popular program on the air.

In their climb to success, the Jordans brought others with them. Don Quinn, of course, is one of the top writers in the radio business. Harold Peary, whose "You're a hard man, McGee," became a national byword has been the star of his own successful program "The Great Gildersleeve," since 1941. One year the McGees had a maid named Beulah, played by Marlin Hurt. Beulah, too, became a star and still is, despite the fact that Hurt, who created the role, has since died. Perry Como once sang during the pleasant musical interludes of the Fibber and Molly program, filled now by the King's Men and Billy Mills' orchestra. And the former drummer in the Mills band was none other than Spike Jones, now also a star In his own right.

In their climb to success, the Jordans brought others with them. Don Quinn, of course, is one of the top writers in the radio business. Harold Peary, whose "You're a hard man, McGee," became a national byword has been the star of his own successful program "The Great Gildersleeve," since 1941. One year the McGees had a maid named Beulah, played by Marlin Hurt. Beulah, too, became a star and still is, despite the fact that Hurt, who created the role, has since died. Perry Como once sang during the pleasant musical interludes of the Fibber and Molly program, filled now by the King's Men and Billy Mills' orchestra. And the former drummer in the Mills band was none other than Spike Jones, now also a star In his own right.Announcer Harlow Wilcox started with the McGees when they first went on the air back in 1935 and is now one of the most sought-after announcers in radio. His reading of Don Qulnn's announcements is always the winner in polls of the most commercial. The other members of the cast—Bill Thompson as the Old Timer and Wallace Wimple, Arthur Q. Bryan as Doc Gamble, and Gale Gordon as Mayor LaTrivia—have earned places in the national consciousness and national heart second only to that large spot occupied by the McGees themselves.

Fibber McGee and Molly are as popular in sophisticated Hollywood as they are in the Jordan's home town, Peoria. The entire radio and motion picture colony turned out to honor them on the occasion of their 10th anniversary in 1944. The same stars will be on hand to wish them well on tonight when they begin their 15th year on the air.

The first show appeared on NBC on April 16, 1935 and moved from Monday to Tuesday on March 15, 1938. Johnson Wax of Racine, Wisconsin was the long-time sponsor through the ‘30s and ‘40s. But then television started siphoning off the advertising money that used to go into radio. Johnson dropped Fibber, who picked up some new sponsors. Soon, it was shed of its orchestra, studio audience, and some secondary supporting players, becoming a daily, transcribed, 15-minute show on NBC from 1953 to 1957. Harlow Wilcox was replaced by John Wald. After that, it was a shell of itself. Jim and Marian Jordan recorded some short dialogues for NBC’s “Monitor” programme before being shoved out the door. The Jordans avoided television; a Fibber and Molly TV show with Bob Sweeney and Cathy Lewis never found an audience.

Marion Jordan died in 1961. Jim followed in 1988.

Quinn looked at the show after its demise and stated that it was vague in a lot of areas on purpose. “We preferred to let the audience paint its own scenery,” he told wire service writer Bob Thomas. “It seems to me television doesn’t give enough credit to the audience’s I.Q.—imagination quotient.”

Imagination was not only what Fibber and Molly was about. It was the keystone behind old radio itself.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)