The radio warns of an explosive-filled white mouse that could blow up the whole city. Tom listens as a newscaster cautions: “The slightest jar will explode this white mouse.”

Jerry, just before this, has been covered with white liquid shoe polish. “Aha!” he thinks.

Something tells me we can both figure out the story of this one. (The Missing Mouse was released in 1951).

Tom, who has heretofore never been known for eating walnuts, decides the first thing to do upon hearing the news is to bash open some nuts with a mallet (without even looking at what he’s doing). Jerry decides to get in the way. Tom brings down the mallet. There’s a brake screech sound effect (by Jim Faris, I believe). That sets up the big reaction.

Phone: Brrringgg!

Hanna: Is this Dick Lundy? This is Bill Hanna. Did Tex Avery leave any spare takes lying around your unit before he left? He did?! Send one over right away.

Here’s the Avery-esque take. There are two drawings. Hanna alternates them, and leaves the cycle on the screen long enough to register.

Does the white paint wash off? Does the real white mouse show up? Does he blow up? I think you know the answers to these.

The usual four T & J animators get screen credit. Scott Bradley is away so Edward Plumb scored the short (I notice no difference) and Bob Gentle receives a background credit. Paul Frees is doing an odd announcer voice as the newscaster.

Friday, 27 January 2023

Thursday, 26 January 2023

Ub's Alien Woman

Grim Natwick was the man who developed Betty Boop for the Fleischer studio, and when he moved across the country to Ub Iwerks’ studio in Beverly Hills, Willie Whopper had a part-time girl-friend named Mary who rather suspiciously resembled Betty.

There was another female character, albeit a one-shot, in another Willie cartoon. Whether Natwick was responsible, I don’t know, but this more realistic, sultry female was certainly within his ability to animate.

She’s in Stratos-fear (1933), in which Willie floats to a mysterious planet full of cool futuristic mechanical designs. She dances out of what resembles a coffin, kisses Willie, and the two walk up a flight of stairs when a door opens.

So much for stairs. The cut in the scene reveals they are coming out of an elevator.

The woman walks like an Egyptian, stops, then reveals herself to be the alien whom Willie is trying to avoid.

Iwerks’ name is the only one on this short, so we don’t know who animated it, who created the story or who was responsible for the settings. There’s imagination aplenty in this cartoon and it’s a shame few other of the Willies matched it.

There was another female character, albeit a one-shot, in another Willie cartoon. Whether Natwick was responsible, I don’t know, but this more realistic, sultry female was certainly within his ability to animate.

She’s in Stratos-fear (1933), in which Willie floats to a mysterious planet full of cool futuristic mechanical designs. She dances out of what resembles a coffin, kisses Willie, and the two walk up a flight of stairs when a door opens.

So much for stairs. The cut in the scene reveals they are coming out of an elevator.

The woman walks like an Egyptian, stops, then reveals herself to be the alien whom Willie is trying to avoid.

Iwerks’ name is the only one on this short, so we don’t know who animated it, who created the story or who was responsible for the settings. There’s imagination aplenty in this cartoon and it’s a shame few other of the Willies matched it.

Labels:

Ub Iwerks

Wednesday, 25 January 2023

A Visit by Ray (No Bob)

Some fans of Bob and Ray like to engage in an exercise where they pick their favourite version of the twosome’s radio show.

Some fans of Bob and Ray like to engage in an exercise where they pick their favourite version of the twosome’s radio show.

They’re all a little different, and there’s something to like in almost all of them.

The half-hours from Boston have funny elements; it’s shame the versions of the broadcasts you can listen to on-line are not the best quality (it’s almost like they had been dubbed onto a cassette or a reel running at the wrong speed and then posted). Bob’s Mary McGoon is generally funny (and she sang the ‘cow in Switzerland’ song) and I love Bob’s send-up of Arthur Godfrey.

They arrive in New York in July 1951, and “present” the NBC radio network, scrunched down to 15 minutes, and far more structured. I enjoy Paul Tauman’s musical breaks, there are a lot of funny offers, a few running gags (Woodlo) and clever re-workings of things they ad-libbed in Boston. This is where Wally Ballou was developed as a character (he started out sounding like Elmer Fudd).

Mutual? Eh. The show stops for pop music records and it’s jarring hearing an actual announcer instead of a phoney Bob or Ray one.

The 15-minute-shows from CBS sound like Bob and Ray went into a studio and cut a week’s worth of shows. The satire takes aim at deserving targets, including network president Frank Stanton’s “programme honesty” directive in the wake of the game show scandal. There are a lot of very fun one-time sketches, and I love “Mr. Science.”

The two were about to arrive at CBS when this article appeared in the May 28, 1959 edition of the Springfield (Ohio) Daily News. Ray stops for an interview during a trip, and runs down some of the funny free offers from previous versions of the show, and their work making quirky animated spots in New York (like Stan Freberg, they first made fun of advertising, then went into it).

Ray Goulding, Deep-Voiced Member Of ‘Bob And Ray’ Comedy Team, Visits Here

By JIM DUFFY

He sat in the office of the placement director of Wittenberg College Wednesday looking not unlike a professor who had an hour to kill.

His legs were crossed as he leaned on the window sill and looked at the students walking between the buildings of the campus. He had black wavy hair with a touch of gray. His accent could be traced to the east coast as he chatted with Col, William H. Miles, college placement bureau director.

But the man in the expensive-looking plaid sport coat was not a member of the faculty. In fact, his reputation places him far from the staid atmosphere of a midwestern college.

The man was Ray Goulding, the deep-voiced half of the zany radio team of “Bob and Ray."

Ray, as he likes to be called, and his wife are in Springfield until Friday visiting with Col. and Mrs. Miles. Mrs. Goulding and Mrs. Miles are sisters.

Ray’s answer to my first question (What are you doing in town?) gave me some idea of what I was in for.

“I’m trying to get into this college, if they'll let me," was the reply. This answer set the pace for the interview.

In case some people happened to have just arrived from the moon and don't know about the comic pair, “Bob and Ray," they have a unique, weird type of humor based on incongruity and a talent in finding something funny in even the most mundane and ordinary situations. The team has been a regular feature of NBC-Radio's “Monitor” program heard on weekends, but in June will begin a regular nighttime 15-minute show on CBS five nights each week.

The team of Bob Elliot and Ray Goulding had its first fateful fusion on a Boston radio station in 1946.

“Bob and I were both staff announcers on WHDH there,” he recalled. “I was doing early morning news and Bob was doing early morning music.”

“Well, the news was bad and the music worse,so we just began ad libbing The routines got silent approval from the boss, so we kept it up. At least we weren't fired.”

“Our early stuff was mostly parodies and satires on soap opera and other radio material,” Ray explained. “We just tried to be funny.”

In 1951 the pair went on television. Their “Gal Friday" was Audrey Meadows, one of the brightest lights in show business today.

“Audrey was a fine, sharp gal," Goulding said. “She could ad lib like mad.”

“They just draw pictures to our old scripts and put it in the magazine,” was Ray’s explanation.

Speaking of “Mad,” Bob and Ray are regular contributors to that off-beat humor magazine.

Speaking of “Mad,” Bob and Ray are regular contributors to that off-beat humor magazine.Some of the pair’s routines have made headlines. A few years ago they offered one of their numerous, but mythical, kits to the public. This particular “kit" included material to make your new house look old. For the listener to receive the material all they had to do was send a postcard to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

“Well," said Ray, “those two little men with green eyeshades and sleeve garters who run that place were deluged with mail. They never saw anything like it.”

But the Smithsonian episode didn't stop them.

Later they invited the audience to procure their handy “Burglar’s Kit” from the Chief of Police in Jefferson City, Mo. The Smithsonian mail barrage repeated itself there.

Once the looney twosome had to return hundreds of dollars in dimes and nickels to listeners who sent 15 cents for torn bed-sheets “guaranteed to be in shreds.”

“We made the price too low,” Ray said. “If we would have asked $500 and still gotten money, we both would have quit radio and gone into the torn sheet business.”

Goulding has been in radio since he was 17. He now lives with his wife and four children in Manhasset, Long Island, outside of New York City. Elliot also has four youngsters but he and his wife live right in the city.

Most of Bob and Ray's present time is spent in their latest endeavour, the animated commercial business. Among their creations are the Piel's Beer boys, “Bert and Harry,” who won many advertising awards.

Tip Top Bread’s “Emily Tipp, the Tip Top Lady” seen in this area is the imaginative result of the productive minds of Elliot and Goulding.

They’ve also video-taped a new television show that is for sale.

Ray expresses the hope that something has to be done about radio. “All we have now is juke box which won't take coins. All day long just disc jockeys and the top 10, top 40, or top 2000,” he says.

There are two kinds of people in this country. Those who rate Bob and Ray tops in humor, and those who just don't understand and therefore cannot laugh at them.

Fortunately for comedy, the former far outnumber the latter. In fact, when I hear one of their routines and the person with me doesn't burst out laughing, I feel rather sorry for him.

If he only knew what he's missing.

Labels:

Bob and Ray

Tuesday, 24 January 2023

Now, An Optical Illusion

The gags from Tex Avery and credited storyman Dave Monahan in Believe It Or Else run the gamut from surreal to obvious. A guy drinks a lot of milk and goes “moo.” Fortunately, Tex tried for something better as the cartoon carried on.

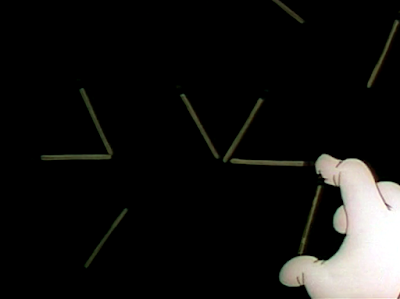

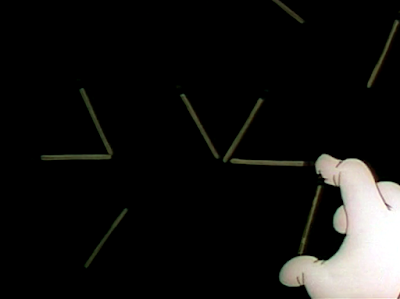

One of the odd ones is an “optical illusion” where the narrator says he can show how you can get 37 triangles out of three triangles made of match-sticks. I’m sure this must be a send-up that appeared in the “Believe it or not” newspaper column.

How does it happen? You move one stick here, this stick there, and.....

The happy Ripley-stand-in narrator ignores the impossibility of it all, in the best part of the scene. “There now. Isn’t it easy?” Try it on your friends.”

Fade out into the next scene.

The running presence of Egghead helps the cartoon. It’s one of Avery’s better spot-gaggers.

Virgil Ross is the credited animator. Keith Scott wonders if the narrator is Cliff Nazarro, forsaking his double-talk routine.

One of the odd ones is an “optical illusion” where the narrator says he can show how you can get 37 triangles out of three triangles made of match-sticks. I’m sure this must be a send-up that appeared in the “Believe it or not” newspaper column.

How does it happen? You move one stick here, this stick there, and.....

The happy Ripley-stand-in narrator ignores the impossibility of it all, in the best part of the scene. “There now. Isn’t it easy?” Try it on your friends.”

Fade out into the next scene.

The running presence of Egghead helps the cartoon. It’s one of Avery’s better spot-gaggers.

Virgil Ross is the credited animator. Keith Scott wonders if the narrator is Cliff Nazarro, forsaking his double-talk routine.

Labels:

Tex Avery,

Warner Bros.

Monday, 23 January 2023

Who Needs Spinachk?

“If it’s good enough for that sailor man,” declared an explorer in Frank Tashlin’s The Major Lied Till Dawn at Warners, “it’s good enough for me.” That’s the attitude taken in the first UPA cartoon for Columbia, Robin Hoodlum (released Dec. 23, 1948).

The Merry Men realise Robin must have been captured because he missed tea time. To the castle they go to rescue him. Arriving at the door of the dungeon, there is a polite knock.

The executioners shoot their arrows at Robin.

Little John bursts into the room with a tea cart. Robin drinks the tea. It gives him strength to break the ropes holding him and jump out of the way of the arrows.

It’d be funny if the Popeye theme was scored under the tea drinking, but UPA never went in for laughs like that.

Those arrows had to be the world’s slowest for all this business to happen before they reached Robin.

Phil Eastman and Sol Barzman came up with the story for this Oscar-nominated short, directed by John Hubley. It certainly won’t remind you of a conventional Fox and Crow cartoon that Columbia made on its own.

The Merry Men realise Robin must have been captured because he missed tea time. To the castle they go to rescue him. Arriving at the door of the dungeon, there is a polite knock.

The executioners shoot their arrows at Robin.

Little John bursts into the room with a tea cart. Robin drinks the tea. It gives him strength to break the ropes holding him and jump out of the way of the arrows.

It’d be funny if the Popeye theme was scored under the tea drinking, but UPA never went in for laughs like that.

Those arrows had to be the world’s slowest for all this business to happen before they reached Robin.

Phil Eastman and Sol Barzman came up with the story for this Oscar-nominated short, directed by John Hubley. It certainly won’t remind you of a conventional Fox and Crow cartoon that Columbia made on its own.

Labels:

UPA

Sunday, 22 January 2023

Larry Adler on Jack Benny

Jack Benny had his radio gang—Mary, Phil, Dennis, Rochester—but he had another gang, too.

During the war, Jack entertained troops in various spots around the world, but his radio cast didn’t come with him. He had singers and others, but one person stood out—harmonica player Larry Adler.

Adler did several tours with Jack, so Benny must have liked him. Adler seemed to have liked Jack; he wanted to tour in Korea with him in the ‘50s but was rejected by the U.S. government as Adler had fallen under the Blacklist and moved to England.

Not surprisingly, Adler wrote about Jack in several places his autobiography “It Ain’t Necessarily So” (1985, published in London by Fontana). One story has been repeated in other publications, but Adler was a witness.

The second story is typical off-mike Mary.

The third story is a downside of Jack’s many, many attempts to reach friends and families of servicemen overseas to reassure them they’re okay. Adler knows his readers can read between the lines.

The blacklist intimidated just about everyone (except people making money from it). Including Jack Benny when it came to Adler’s court case.

There is another reference to Jack, though it mainly involves his wife Mary Livingstone. There are fans of the Benny show who "know" her solely based on her radio performances. They think she’s wonderful and angrily dismiss any untoward comments about her life off-the-air. Mary was not popular among some people who actually knew her personally. Adler was one.

It simply confirms what his fans have thought all along.

During the war, Jack entertained troops in various spots around the world, but his radio cast didn’t come with him. He had singers and others, but one person stood out—harmonica player Larry Adler.

Adler did several tours with Jack, so Benny must have liked him. Adler seemed to have liked Jack; he wanted to tour in Korea with him in the ‘50s but was rejected by the U.S. government as Adler had fallen under the Blacklist and moved to England.

Not surprisingly, Adler wrote about Jack in several places his autobiography “It Ain’t Necessarily So” (1985, published in London by Fontana). One story has been repeated in other publications, but Adler was a witness.

In general Jack Benny was mild-mannered, anything for peace and quiet. I saw him angry just once, after we had done an open-air show in Benghazi. Halfway through, a sand storm started, blowing directly into our faces and completely ruining one of my few good mouth-organs. (They were made in Germany and, once the war began, the supply of mouth-organs stopped.) After the show we had coffee and doughnuts in a Red Cross canteen. After such an unpleasant experience, coffee and doughnuts lacked something. A lieutenant came over and, without invitation, sat at our table. When he opened his mouth his heavy Southern accent made Stepin Fetchit sound like Abe Lincoln.One story shows that the line about Jack needing his writers to respond is a canard. Adler was hired for Sensations of 1944, got into high dudgeon and walked off the picture.

‘Hiya, Jack’, he said, pronouncing it ‘jay-yuck’.

‘Hi’, said Jack, wearily.

‘Hey, Jay-yuck, how come y all didn’t bring Rochestah?’ (The black man who was Jack’s butler on his radio show.)

Jack said that Rochester had commitments at home.

‘Thay-yuts a goddam shame, pahdon mah French’, he ‘said. ‘Y’know, back home in Tallahassee, m’wife and me, ‘we listen in evah Sunday night, wouldn’t miss it foh the world. But s**t, man, that Rochestah, whah, he’s ninety percent of yoah show.’

‘Sure do! Not to say y’all ain’t veh funny, Miz Benny, but s** man, m’wife and me, we just crazy ‘bout that Rochestah.’

‘Okay’, said Jack, ‘now let’s suppose we had brought him. He'd be sitting at this table with us. How would you like that?’

‘Now just you hold on one minute’, said the lieutenant. ‘Ah’m from the South!’

‘That’, said Jack, ‘is why I didn’t bring Rochester.’

That summer, at Guadalcanal, I saw Sensations scheduled for an afternoon showing for the troops. Jack Benny came with me to see what the film world had lost by my obstinacy. There was a circus scene that featured Pallenberg’s Bears. At one point a bear kept riding a motorcycle around a ring.Here are three stories Adler tells in succession. The first one is prefaced with a long story involving two typical Jack Benny traits: he fell down laughing at other people’s jokes, and he thought everything was the best. There are all kinds of tales about “this is the best coffee I ever had” or “these are the softest sheets I ever had.” Adler made a quip that Jack decided made him the funniest man in the world. Adler wasn’t crazy about it, but George Burns seized on the lame line and Jack’s reaction, and added that to his talk-show repertoire. The story concludes with Jack trying to help Adler, again something he did for friends.

‘Look at that,’ I said to Jack, ‘that poor bear’s in a rut.’

‘It’s worse than you think’, said Jack. ‘That animal, through no fault of his, is now type-cast. In every picture, he’ll have to be a bear.’

The second story is typical off-mike Mary.

The third story is a downside of Jack’s many, many attempts to reach friends and families of servicemen overseas to reassure them they’re okay. Adler knows his readers can read between the lines.

When we returned from the African trip in 1943 Jack Benny told John Royal, a vice-president of NBC, that I should write and star in my own comedy programme. Because it was Jack who said it, Royal had to take it seriously. He phoned me, I met him at his office in Radio City, and when he told me what he proposed, in line with Jack’s suggestion, I panicked.Naturally, Adler spends a fair portion of the book dealing with the ridiculous and odious blacklist. He decided to sue a woman who wrote a letter to her local paper that he was pro-Communist and his pay from a local event would go to Moscow to be used to destroy America.

‘My God’, I said, ‘I can’t do that! It’s one thing to write a programme around Jack. Hell, anybody could do it, with all his stereotypes, the stinginess, the bear, Rochester, and stuff. But I couldn’t write for me — I haven't any personality.’

John Royal didn’t press the idea. I may well have been an idiot but I do not think I could have done it.

In Omdurman, during the African trip, Jack and I visited the best PX (Post Exchange) I’ve ever come across. Julie Horowitz, an Army captain, who was in charge of it, had ivory, African wood-carvings, Egyptian sandals, all sorts of things such as I’ve never seen in any other PX. We bought things for our wives and Julie arranged to have them shipped back.

At the Stork Club in New York, several months later, Mary Benny asked Eileen, ‘Tell me, honey, did Larry send you back the same lot of s**t that Jack sent me?’

Jack had promised Horowitz he’d phone his fiancée who worked at Macy’s in New York. I was with Jack when he phoned her.

‘Miss Cohen? This is Jack Benny.’

‘Oh, yes,’ she said.

‘I’ve just returned from the Middle East. I ran into your fiancé, Julie, in Omdurman.’

‘Oh, did you?’ said Miss Cohen. She was making it tough going.

‘Julie’s looking fine’, said Jack, ‘and he sends you his love.’

‘That’s nice’, said Miss Cohen. ‘Was there anything else?’

“Well – uh – no, I don’t think so.’

‘Thank you’, said Miss Cohen. ‘Nice of you to call. Goodbye.’

Jack just looked at me after he hung up.

The blacklist intimidated just about everyone (except people making money from it). Including Jack Benny when it came to Adler’s court case.

But Jack Benny called me to his house to tell me that he had been advised by his business manager — who was also his brother-in-law — that he must not appear. He was commercially sponsored and could lose that, were he seen to be lending support to a leftie - a pinko - a Red, or whatever. Jack seemed distressed as he said this; I think he would rather not have said it and, on his own, | don’t think he would have said it. But I had never intended to call Jack, I knew how vulnerable he was. Sponsors don’t like knocking letters and just a few can cause a performer to be taken off the air. I doubt whether that would have happened to Jack Benny, but I wouldn’t put him on the spot.Adler lost the case.

There is another reference to Jack, though it mainly involves his wife Mary Livingstone. There are fans of the Benny show who "know" her solely based on her radio performances. They think she’s wonderful and angrily dismiss any untoward comments about her life off-the-air. Mary was not popular among some people who actually knew her personally. Adler was one.

I took Ingrid [Bergman] to a party at Jack Benny’s. She came to me in a panic. L. B. Mayer kept trying to paw her and she couldn’t stand it. She wanted to leave but Jack’s wife, Mary, made such a scene about it that we stayed.Perhaps the most interesting revelation about Jack’s character goes back to one of the war-time excursions. An emergency signal came from a military base in Africa for the Benny plane to land. The plane was too big for the airstrip and there was a crash landing. Everyone was okay. Then the signallers revealed that there was no emergency; they knew Benny was on the plane and they wanted to see his show. Adler was outraged because everyone on the plane could have been killed. He refused to perform. But Jack did. Adler pointed out that Jack was always good-natured.

Jack Benny had the idea of ‘love me, love my friends’, and often tried to bring me together with his group, really Mary’s, who were mainly right-wing. After a preview in Jack’s projection room, showing Double Indemnity, I started to congratulate Barbara Stanwyck (for British readers that is Stan-Wick, not Stannick). She cut me short. ‘Jack’s told me about you and your liberal bulls**t; I hope we're not going to have to listen to that crap all evening.’ . . .

Jack, Mary, Eileen and I went to a Jerome Kern concert at the Hollywood Bowl. Eileen drove in Jack’s car, Mary with me. Mary asked: ‘Tell me, Larry, when you were with Jack on these tours, did he cheat?’ I was appalled. ‘Oh, come on, it’s just between us. I’d never say a word to Jack.’ I said the question was revolting, she should never have asked it and, were she not Jack’s wife, I'd have asked her to get out of the car. Relations were distant after that. Some time before, she was in her car with the top down; I in mine, also with the top down. At a traffic stop, our cars side by side, she bellowed an intimate question about Ingrid to me. A lot of people must have heard her and I’m certain she did it deliberately. Not a nice lady.

It simply confirms what his fans have thought all along.

Labels:

Jack Benny

Saturday, 21 January 2023

The Teenager Who Would Be Disney

In 1960, he had a cartoon studio on Cahuenga Boulevard and invented a caveman named Fred.

Bill Hanna? Joe Barbera? Dan Gordon or Harvey Eisenberg, maybe?

No. The cartoonist in question is Earle Nimmer Lemke, Jr.

Earle was a teenager who wanted to be the next Walt Disney, though he kind of started out like Hanna-Barbera. He was profiled in the Van Nuys News, August 12, 1960. When we originally posted this article on GAC, a picture accompanied it. Unfortunately, it’s not available now.

Animated Cartoon Field Beckons to Local Teen

Cartoonist and Sherman Oaks resident Earl Lemke 19, is not only a very talented and creative young man, but a most determined one who so far appears to be leaving no stone unturned in carving his own career—that of producing animated film cartoons.

Earl will graduate from Montclair College Preparatory School in January.

Set for SC

After this he plans to attend University of Southern California to major in cinematography, with supplementary courses at an art school and a stint of practical experience at a major film cartoon studio.

However, even though his higher education is well in view, he already has launched upon the career which he forsees as “in full operation, financially successful” by the time he emerges with his college degree.

Up to this time “entirely self-educated” in his chosen field, Earl says he avidly started, at the age of 13, to read everything and anything on the subject of motion picture making and, more specifically, cartoon filming.

He lives with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Earl Lemke, at 15925 West Meadowcrest Road, Sherman Oaks.

Up to four months ago the home had more or less become converted to a production studio, his acquired and handmade equipment having taken over Earl’s bedroom, the garage and most of the rest of the house.

Up to four months ago the home had more or less become converted to a production studio, his acquired and handmade equipment having taken over Earl’s bedroom, the garage and most of the rest of the house.

Then he decided to open his own production studio, “Earl Lemke Productions,” at 3491 Cahuenga Blvd [photo at right].

Own Studio

Here Earl has underway, a single man operation, a cartoon film, producing studio where the visitor will note everything from neat rows of filing cabinets to rows of “rough” drawings lining one wall, and from drawings traced and painted on cellulose [sic] (called “cells”) [sic] to a monster-looking “animation stand.”

Getting ready for business, Earl Lemke Productions has already produced one pilot film to show what can be done and with the aim of getting orders for one-minute television film commercials and eventually, full-length cartoons.

He recently completed his first educational film cartoon—a three-minute feature illustrating the principles involved in good public speaking and featuring pre-historic characters named “Fred,” “George” and “The Chief”— with Max the Dinosaur thrown in for good measure.

Script and planning were done with Mrs. Joann Simpson of Montclair where the film will be used in the fall for an illustration of “do’s and don’t” in public speaking, making Montclair the studio’s first bonafide “customer.”

Earl already has had two of his character creations copywrited — “Geemo the Lion” and “Zeek.”

Gemo took some three months to perfect to Earl’s satisfaction. Zeek, devised simply to accompany Geemo, was created in one day. Earl credits his English teacher, Joan Kirkby, with getting him started on animating his cartoon subjects.

Does Project

She suggested that for a classroom project he draw an English squire for the “Canterbury Tales”—with the result that he did enough drawings of the Squire to make a “flip book.”

Earl’s idol is Walt Disney, whom he has never met but whose biography he has read from cover to cover and whom he hopes to meet sometime at what he anticipates as “the greatest thrill in store for me.”

Drawings of GeeMo the Lion and Zeek were copyrighted October 7, 1959 and Geemo the Lion as found in some publication was copyrighted October 14, 1960. The following year, Lemke produced a six-minute colour film called “A Boogle, Da Moogle, Da Clug.” It was copyrighted on August 14, 1961. What it was about, I have no idea. His name is found in one more copyright catalogue, dated June 16, 1964, for three poses of a character named Gary Goose.

His company was still listed in the directory of the SMPTE of March 1974. But what became of Earle and his dream are bits of information we have yet to discover.

Bill Hanna? Joe Barbera? Dan Gordon or Harvey Eisenberg, maybe?

No. The cartoonist in question is Earle Nimmer Lemke, Jr.

Earle was a teenager who wanted to be the next Walt Disney, though he kind of started out like Hanna-Barbera. He was profiled in the Van Nuys News, August 12, 1960. When we originally posted this article on GAC, a picture accompanied it. Unfortunately, it’s not available now.

Animated Cartoon Field Beckons to Local Teen

Cartoonist and Sherman Oaks resident Earl Lemke 19, is not only a very talented and creative young man, but a most determined one who so far appears to be leaving no stone unturned in carving his own career—that of producing animated film cartoons.

Earl will graduate from Montclair College Preparatory School in January.

Set for SC

After this he plans to attend University of Southern California to major in cinematography, with supplementary courses at an art school and a stint of practical experience at a major film cartoon studio.

However, even though his higher education is well in view, he already has launched upon the career which he forsees as “in full operation, financially successful” by the time he emerges with his college degree.

Up to this time “entirely self-educated” in his chosen field, Earl says he avidly started, at the age of 13, to read everything and anything on the subject of motion picture making and, more specifically, cartoon filming.

He lives with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Earl Lemke, at 15925 West Meadowcrest Road, Sherman Oaks.

Up to four months ago the home had more or less become converted to a production studio, his acquired and handmade equipment having taken over Earl’s bedroom, the garage and most of the rest of the house.

Up to four months ago the home had more or less become converted to a production studio, his acquired and handmade equipment having taken over Earl’s bedroom, the garage and most of the rest of the house.Then he decided to open his own production studio, “Earl Lemke Productions,” at 3491 Cahuenga Blvd [photo at right].

Own Studio

Here Earl has underway, a single man operation, a cartoon film, producing studio where the visitor will note everything from neat rows of filing cabinets to rows of “rough” drawings lining one wall, and from drawings traced and painted on cellulose [sic] (called “cells”) [sic] to a monster-looking “animation stand.”

Getting ready for business, Earl Lemke Productions has already produced one pilot film to show what can be done and with the aim of getting orders for one-minute television film commercials and eventually, full-length cartoons.

He recently completed his first educational film cartoon—a three-minute feature illustrating the principles involved in good public speaking and featuring pre-historic characters named “Fred,” “George” and “The Chief”— with Max the Dinosaur thrown in for good measure.

Script and planning were done with Mrs. Joann Simpson of Montclair where the film will be used in the fall for an illustration of “do’s and don’t” in public speaking, making Montclair the studio’s first bonafide “customer.”

Earl already has had two of his character creations copywrited — “Geemo the Lion” and “Zeek.”

Gemo took some three months to perfect to Earl’s satisfaction. Zeek, devised simply to accompany Geemo, was created in one day. Earl credits his English teacher, Joan Kirkby, with getting him started on animating his cartoon subjects.

Does Project

She suggested that for a classroom project he draw an English squire for the “Canterbury Tales”—with the result that he did enough drawings of the Squire to make a “flip book.”

Earl’s idol is Walt Disney, whom he has never met but whose biography he has read from cover to cover and whom he hopes to meet sometime at what he anticipates as “the greatest thrill in store for me.”

Drawings of GeeMo the Lion and Zeek were copyrighted October 7, 1959 and Geemo the Lion as found in some publication was copyrighted October 14, 1960. The following year, Lemke produced a six-minute colour film called “A Boogle, Da Moogle, Da Clug.” It was copyrighted on August 14, 1961. What it was about, I have no idea. His name is found in one more copyright catalogue, dated June 16, 1964, for three poses of a character named Gary Goose.

His company was still listed in the directory of the SMPTE of March 1974. But what became of Earle and his dream are bits of information we have yet to discover.

Friday, 20 January 2023

Silhouettes and Auto Workers

Art styles were changing in animated cartoons in the late ‘40s, and there are some good examples in the John Sutherland Productions industrial short Why Play Leap Frog? (copyright March 1, 1949).

In this scene, characters are in silhouette while the background painting of the auto factory is fairly representational, though not as abstract as some artwork would become in the ‘50s.

The Sutherland cartoon cartoons contained some gentle humour to off-set their propagandistic nature (the shorts were pro-big business because big business paid to have them made). See what happens to the auto workers on the assembly line as parts are lowered through the ceiling.

A “What the...?” reaction.

The writer (True Boardman?) ends the scene making fun of gaudy hood ornaments of the era.

A deal was worked out with MGM to put the Sutherland cartoons in theatres. An ad in the Motion Picture Herald of September 2, 1950 says there were 5,025 bookings for this cartoon so far. One theatre manager complained to the publication “These should not be sold as cartoons...there is certainly no humor to them.” The CIO News of March 26, 1951 called it “a sly attack on wage increases.” We’ve talked before here about the controversy surrounding one Sutherland animated short that was accused of criticising U.S. government policy, with MGM subsequently deciding to stick only with Tom and Jerry, Droopy and Barney Bear. Joe the factory worker was out.

Unfortunately there are no credits on the short, so we don’t know the artists. We do know the background music composer, because his name is mentioned in the copyright registration. It’s former Disney composer Paul Smith. The copyright office lists names for some of the cues: “Walking Theme,” “A Raise,” Farm Theme,” “Charts,” “Trouble,” “Production Theme” and “Main Title,” all copyrighted September 26, 1949.

Bud Hiestand is the narrator (evidently the cartoon was reissued because there’s a change in quality of the soundtrack in one version dealing with prices), Frank Nelson provides a couple of voices and I have not been able to discover who played Joe, who starred in the earlier Sutherland cartoon Meet King Joe.

In this scene, characters are in silhouette while the background painting of the auto factory is fairly representational, though not as abstract as some artwork would become in the ‘50s.

The Sutherland cartoon cartoons contained some gentle humour to off-set their propagandistic nature (the shorts were pro-big business because big business paid to have them made). See what happens to the auto workers on the assembly line as parts are lowered through the ceiling.

A “What the...?” reaction.

The writer (True Boardman?) ends the scene making fun of gaudy hood ornaments of the era.

A deal was worked out with MGM to put the Sutherland cartoons in theatres. An ad in the Motion Picture Herald of September 2, 1950 says there were 5,025 bookings for this cartoon so far. One theatre manager complained to the publication “These should not be sold as cartoons...there is certainly no humor to them.” The CIO News of March 26, 1951 called it “a sly attack on wage increases.” We’ve talked before here about the controversy surrounding one Sutherland animated short that was accused of criticising U.S. government policy, with MGM subsequently deciding to stick only with Tom and Jerry, Droopy and Barney Bear. Joe the factory worker was out.

Unfortunately there are no credits on the short, so we don’t know the artists. We do know the background music composer, because his name is mentioned in the copyright registration. It’s former Disney composer Paul Smith. The copyright office lists names for some of the cues: “Walking Theme,” “A Raise,” Farm Theme,” “Charts,” “Trouble,” “Production Theme” and “Main Title,” all copyrighted September 26, 1949.

Bud Hiestand is the narrator (evidently the cartoon was reissued because there’s a change in quality of the soundtrack in one version dealing with prices), Frank Nelson provides a couple of voices and I have not been able to discover who played Joe, who starred in the earlier Sutherland cartoon Meet King Joe.

Labels:

John Sutherland

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)