Leon Schlesinger had big plans for a new cartoon series. It would feature paintings by a well-known and respected artist and uber-cute little boys. Sounds like an attempt to take on Disney, doesn’t it? But after Schlesinger poured out extra money and effort, the series died after one cartoon.

What was the series?

Schlesinger’s aggressive PR flack, Rose Horsley, got material planted on it with various columns (Lolly, Hedda, Fidler) and assorted news agencies and newspapers. Here’s an International News Service story from January 14, 1940.

IN HOLLYWOOD

By BURDETTE JAY

HOLLYWOOD, Jan. 13. (INS)—Leon Schlesinger, who produced the screen's first patriotic cartoon, "Gold Glory" [sic] and originated those popular animated travelogues, will present another innovation to the pen and paintbrush film industry in "Mighty Hunter," first in a series of one-reel Jimmy Swinnerton-"Canyon Kiddies" Technicolor cartoons, which will be released as a "Merrie Melodie" by Warner Bros.

The new idea is backgrounds painted in oils, rather than the usual water color, which have been done by Swinnerton, noted artist and newspaper cartoonist, who also created the screen characters and collaborated on the story.

Swinnerton, famous for his desert landscape paintings, has brought the splendor and colorings of the Grand Canyon and the Painted Desert to "Mighty Hunters," which took 12 months to produce.

A precedent was established in cartoon production when Schlesinger sent Swinnerton, Director Charles M. Jones and several animators to the Grand Canyon and nearby Indian villages to make 16 mm. color pictures for background reference and study native dances, and costumes for this animated subject.

“Canyon Kiddies” was appearing in

Good Housekeeping magazine every month. We’ll likely never know at this late date what induced Schlesinger to decide to turn Swinnerton’s comic into an animated series, but the first hint of him doing it appeared in Lee Shippey’s column in the Los Angeles

Times of November 25, 1938.

Jimmy Swinnerton’s Canyon Kiddies, long featured by a national magazine, are to be put on the screen as animated cartoons.

Schlesinger and his wife boarded the Super Chief for New York on December 27th for meetings with Warners mucky-mucks (

Daily Variety, Dec. 23, 1938). He already had some cartoons for the 1939-40 season in the can (

Variety, Oct. 19, 1938). When he got to his destination, he had an announcement to make.

Film Daily reported on January 6, 1939:

Schlesinger Expects New Short to Require a Year

In wake of his arrival this week in New York from the Coast, Leon Schlesinger, short subjects producer for Warner Bros, at whose home office he is currently discussing preliminary plans for his program of "Merrie Melodies" and "Looney Tunes" for the company's 1939-40 line-up, stated the "Merrie Melodies" series next season is virtually certain to include several subjects delineated by Jimmie Swinnerton, creator of “Canyon Kiddies,” whom Schlesinger recently signed to a contract.

Production will start on the initial "Canyon Kiddies" short on Feb. 6, and the picture will require approximately one year to complete, Schlesinger declared.

There’s a possibility most of the Schlesinger staff had no idea this was happening. Leon arrived back in Los Angeles on January 26th (

Daily Variety, same date) and the studio newsletter,

The Exposure Sheet reported that he had told the staff on his arrival about the series that would “retell old Indian legends” and that Chuck Jones would direct it. Kiddie characters were his forte.

Film Daily of February 9th reported:

Leon Schlesinger has started production on the initial "Canyon Kiddies" cartoon. Jimmy Swinnerton, recently signed to a long term contract, will create the characters and collaborate on the story and draw his inimitable backgrounds. The initial subject as yet untitled will be as a "Merrie Melody" of the 1939-40 program as Schlesinger has room for only one subject on this series. Schlesinger will probably do a series for the 1940-41 schedule.

A February edition of the

Exposure Sheet provided an update:

Due to the unusual backgrounds and customs in the new series of Canyon Kiddies Cartoons, James Swinnerton, Chuck Jones and his story unit, left yesterday morning for the old Indian ruins of Arizona.

Mr. Schlesinger felt that it was quite necessary for the department to be familiar with the general atmosphere of the country.

They took a 16 m.m. camera with which to capture, in color, the Indian dances, settings and characters. They expect to gather enough material on the old Indian legends for the entire series of cartoons.

Isn’t this the first time a cartoon studio has gone out on location for material.

P.S. – Tex Avery’s story unit [Tubby Millar and Jack Miller] swear their next picture will have a Hawaiian background.

Some of the tribulations of the Jones expedition were outlined in a March edition of the

Exposure Sheet. It doesn’t say who went on the trip, but storyboard artist/designer Bob Givens revealed that, at the time, Jones’ story unit was Dave Monahan and Rich Hogan. They rotated credits and Monahan gets screen credit on

Mighty Hunters.

The C. Jones unit’s trip to Arizona for research on “The Canyon Kiddies” was a huge success, their one disappointment being their inability to secure many pictures of the Indians who thought the boys were taking a part of their lives when they snapped any pictures.

On approaching the Indian settlement of Hoteaville, they had a feeling of being in Shangri La because of the detachment and unreality of the place. And although it was almost zero weather, many of the old Indians walked around barefoot.

In one hogan they saw a little old woman of 110 sitting near a stove, and were told she had been there for ten years, getting up only occasionally during the summer. The different tribes’ manner of living was also noted. The Hopis are pretty wealthy and are very commercial. They work well together, and are very friendly – in direct contrast to the Navajos.

The boys were very fortunate in witnessing the ancient Bean Dance which only a hundred or so white men have ever seen; particularly as it may be the last time the Indians will have danced it. The leaders of the dance were all over a hundred years old, and half blind. One was totally blind.

Outstanding, during the entire trip, was the unusually good behavior of the children – parents [remainder of sentence missing ].

Something delayed the Canyon Kiddies project a bit—Leon decided to join the flag-waving going on at the Warners main lot. He announced in late March a patriotic cartoon. The trades reported he assigned as many people as possible to

Old Glory, with Chuck Jones directing. It was finished in ten weeks on June 16th (United Press story).

Then it was back to

Mighty Hunters for a bit. The

Exposure Sheet of August 25, 1939 tracked the progress.

James Swinnerton has completed the oil backgrounds for the first of the “Canyon Kiddies” series – as yet untitled – and has turned them over to the studio.

Chuck Jones’ story unit has finished the story, and with Chuck now working on the timing of the picture, it will soon be in the hands of the animators.

Much interest has been shown around the studio in anticipation of this first picture of the series, and from all reports the finished product will be indeed worthy of praise.

One of the interesting points of the cartoon will be the authentic Navajo music and dances. The backgrounds will also authentically show the Navajo land.

It’s clear, even looking at the murky version of the cartoon in circulation, that Swinnerton did not do all the backgrounds. Once the cartoon shows the kiddies in action, the backgrounds (and character designs) are very much in the style of other Warners cartoons. Art Loomer and Al Tarter were Jones background men in spring 1939. Paul Julian was hired and assigned to the Jones unit in mid-October but it’s unclear if he replaced someone.

Let’s see how the cartoon moved along as reported in the trade press:

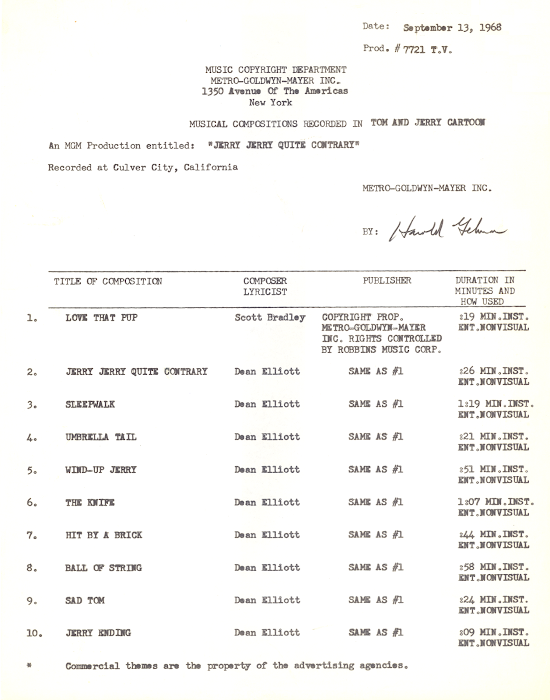

December 11, 1939 (Film Daily)

LEON SCHLESINGER has just put his new "Canyon Kiddies" cartoons ... first of which will be "The Mighty Hunters" ... before the Technicolor cameras for Warner release ... James Swinnerton, originator of the "Kiddies," created the screen characters ... collaborated on the story and painted all the backgrounds ... entirely IN OIL ... for the first time in an animated cartoon ... Schlesinger asserts the oil paintings will give the animated film the same advantage that an oil painting has over water color ... solidity, depth and color effect.

December 13, 1939 (Hollywood Reporter)

Leon Schlesinger will start scoring the first of the Canyon Kiddies-Jimmy Swinnerton cartoons, “Mighty Hunters,” today. Carl Stallings [sic] will conduct the Vitaphone orchestra.

December 22, 1939 (Hollywood Reporter)

Leon and Mrs. Schlesinger leave Tuesday by Superchief for New York where the cartoon producer will spend a month on business. He is taking with him a special Technicolor print of “Mighty Hunters,” the first of his new “Canyon Kiddies” series, to show to Warner home office executives.

January 9, 1940 (Louella Parsons column)

When I return to Hollywood I’m going to have to pay more attention to the animated cartoons—they are so popular across the country. Hear the new little characters Jimmy Swinnerton created for the Leon Schlesinger short, “Mighty Hunters,” are a knockout.

January 14, 1940 (Philip K. Scheuer, Los Angeles Times)

Backgrounds painted in oil, on the increase of late, reach full fruition in Leon Schlesinger’s “Mighty Hunters,” which I viewed last week. This Merrie Melodie is the first animated reel to use oil in lieu of water colors throughout: the artist was Jimmy Swinnerton, noted for his desert landscapes; his setting, the Grand Canyon. A camera unit actually dispatched to the spot to make 16-millimeter color movies for reference. The subject, first of a series about the “Canyon Kiddies,” redskins all, is more impressive than amusing—but probably even the animators were awed. You can’t get flip about a Grand Canyon.

The cartoon was released January 27, 1940.

Parents Magazine liked it.

Boxoffice magazine was lukewarm in its February 10, 1940 edition.

Mighty Hunters

Vitaphone (Merrie Melody) 7 Mins.

Although handsomely drawn and colored in a new oil pigment process, this bit of Indian whimsy is average stuff about children and their escapes [sic]. Based on “Canyon Kiddies” by Swinnerton, the comic strip, the action concerns a couple of kids who meet up with a bear high on the rim of a canyon. Very suitable for juvenile matinees.

But now that the cartoon was released, there was no more talk about a series. It ended with this one cartoon. Chuck Jones, known to pontificate about just about anything in animation, never mentioned the short or series in his two books, except in a filmographic appendix.

Some time ago, Jerry Beck wrote a piece about a full-page comic strip based on the cartoon. It appears to have been in a bunch of the Hearst papers; we’ve found it in the

San Francisco Examiner. You can see a full-colour version

in this post.

For the record, Ken Harris gets the animation credit in this short. Shepperd Strudwick is the narrator; Jones had him play the father in another 1940 release,

Tom Thumb in Trouble. Carl Stalling’s score includes J.S. Zamecnik’s “Indian Dawn” over the opening credits as well as one of his go-to melodies,

“The Sun Dance” by Leo Friedman.