Iwerks’ Animated Pictures Corporation in the Rees Building at 9713 Santa Monica Blvd. had one cartoon series in production, his ComiColor shorts that Pat Powers’ Celebrity Pictures in New York was releasing on a states’ rights basis. And there were no plans to stop.

In fact, there was talk of expansion. Film Daily reported on February 26, 1936

In addition to a fourth series of ComiColor Cartoons already planned for 1936-37, P. A. Powers will expand the activities of his Celebrity Pictures by producing a new cartoon series based on the Gene Byrnes newspaper strip, "Reg'lar Fellers", under a deal made by Charles Giegerich of Celebrity. Both series will be produced under the directorial supervision of Ub Iwerks.And on April 28th:

Under present plans Celebrity proposes to produce a series of six "Reg'lar Fellers" cartoons in addition to a fourth ComiColor series, but it has not yet been decided whether "Reg'lar Fellers" will be in black and white or in color. The ComiColors will continue to be processed in Cinecolor.But Powers wanted more control. This story appeared on May 18th:

The last ComiColor cartoon on the current schedule of Celebrity Productions is now in work, with completion expected far in advance of original listing.

The P. A. Powers ComiColor Cartoons and the new series of "Reg'lar Fellers" cartoons for 1936-37 may be made in New York instead of Los Angeles, according to new production plans being considered by Celebrity Productions. Harry A. Post, vice-president of Celebrity, is en route to the coast to confer with Cartoonist Ub Iwerks on the practicability of moving the entire animating plant to New York or the advisability of separating production, with the new "Reg'lar Fellers" series to be made in New York while the ComiColors would continue to be produced at the Beverly Hills studio.It would be easy to speculate that Iwerks refused any changes and Powers pulled the financial rug from under him in response. But we do know that the ComiColor series ended and Animated Pictures Corporation closed its doors. (Composer Carl Stalling told author Mike Barrier he was only out of work for a few weeks before he went to Warner Bros. on the recommendation of Bugs Hardaway).

As for “Reg’lar Fellers,” one cartoon was made and released as a ComiColor short. It was titled Happy Days. Some extra expense was involved as child actors were hired for the parts.

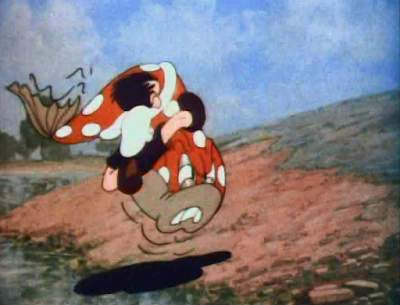

I don’t know who was employed at the studio at the time, other than Stalling and animator Irv Spence, but here are some frames from the climax scene where Pinhead wrestles a big fish that he has caught, or caught him. The animation is very good; I especially like the multiples and expressions, though this public domain DVD makes them hard to see. The director made an odd choice to leave the foreground action in place while suddenly changing the background to include another boy.

Happy Days was released September 30, 1936. And that was it. Kind of.

Iwerks found himself in the subcontracting business. Charles Mintz hired him to help fill the Columbia release schedule, so Animated Pictures reopened and made Skeleton Frolics, which was released January 29, 1937. How long Iwerks had the contract is unclear, but the trade papers reported he directed these cartoons for Mintz (I’ve included several listed in Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice and Magic):

Merry Mannequins, released March 19, 1937

The Foxy Pup, May 21, 1937

Spring Festival, August 6, 1937

The Horse on the Merry-Go-Round, February 18, 1938

Snowtime, April 14, 1938

The Frog Pond, August 12, 1938

Midnight Frolics, 24, 1938

The Gorilla Hunt, 24, 1939

Nell’s Yells, June 30, 1939

Crop Chasers, September 22, 1939

Blackboard Revue, March 15, 1940

The Egg Hunt, May 31, 1940

Ye Olde Swap Shoppe, June 28, 1940

Wise Owl, December 6, 1940

One wonders how he and Mintz got along, for it was Mintz who went behind Walt Disney’s and Iwerks’ back to hire virtually the rest of their staff and take over the Oswald release for Universal from them.

Ub also had a deal with Leon Schlesinger which saw him supervise Porky and Gabby, released May 15, 1937 and Porky’s Super Service, July 3, 1937.

The book “The Hand Behind the Mouse” says Ub was running behind on the Porky cartoons, so he up and quit in mid-May 1937. Bob Clampett took over as director the next day, walking right in to Iwerks’ studio, sitting at Iwerks’ desk, and using Iwerks’ animators (the operation was moved back to the main lot about a month later). Later in 1937, another angel came forward to set him up in a business. Motion Picture Daily reported at the end of the year:

Hollywood, Dec. 13. — Backed by British capital represented by Lawson Haris and having release contracts in Great Britain already signed with the newly formed British Independent Exhibitors' Ass'n, Cartoon Films, Ltd., a new corporate setup for Ub Iwerks, this week started production of 24 color cartoons depicting Lawson Wood's famous Collier's Magazine cover ape, "Gran'pop."Evidently the cartoons took some time to complete. A year later, Film Daily of December 19, 1938 reported three of the cartoons had been made. They were apparently the only ones that were finished. The Hollywood Reporter of the same day blurbed:

The Beverly Hills studios of the company increased its capacity and is using RCA sound. Haris is president.

"Gran'pop's Busy Day" will be the title of the first picture.

Earl W. Hammons [sic] has closed a five year contract with David Biederman for a series of animated color cartoons to bear the Educational trademark and be distributed through Grand National. Funny Ole Monkey and His Chimp Nephews will be starred in the Biederman Productions, to be directed by U.B. Iwerks, and produced under contract with Animated Cartoons, Inc., Beverly Hills. Eight cartoons will be released the first year, with 12 to be made each season thereafter.The following day, the paper added:

Animated Cartoons, Inc., will start on its first subject for Grand National release immediately on signing for a color process, several of which are now being considered. Shorts will be under the direction of Paul Fennell. The company will make 12 one-reel shorts for five years.Fennell later took over managing the company, which also made animated commercials.

(A side note: Billboard of January 25, 1939 noted “Jacques Press signed to compose and score [t]he music for a series by Animated Cartoons, Inc.”).

“The Hand Behind the Mouse” says the Gran’ Pop characters were different than anything else Iwerks had worked with and were difficult to animate. As for his work for Columbia, Iwerks simply got tired of animation and wanted to move on. He accepted a paltry $75 a week from Ben Sharpsteen and rejoined the Disney Studios on September 9, 1940.

Ub went on to invent new developments for film, was handed Oscars, and historians started examining Pat Powers’ belief in 1930 that Iwerks was the true brains behind Walt Disney’s success. That’s not altogether correct, but Iwerks is now recognised for being more than someone who was a top artist in the late 1920s.