The first made-for-TV animated cartoons apparently appeared in 1929. At least, that’s what the

Philadelphia Inquirer of May 19th of that year reported.

The newest thing in the broadcasting of television material seen is in the production of a series of short motion pictures, especially suitable for transmission at the present stage of the art, by Visugraph Pictures, Inc. These productions will consist of simple sketches and animated cartoons that are especially adapted for the purpose. They are being produced for transmission from Station W2XCR, at Jersey City, owned and operated by the Jenkins Television Corporation, and they may be tuned in at will by radio “lookers-in” who have receiving sets equipped for television reception and reproduction.

I have no idea if any cartoons were made, let alone have survived.

Cartoons and TV have been together longer than you probably realise. Old silent animated theatrical shorts were part of the regular broadcast schedule of W2XR in Long Island City in 1931. After World War Two, several enterprising people looked at the challenges of making cartoons especially for the small screen. It boiled down to money. Making cartoons like the ones in theatres in the volume needed for TV could never be profitable. Something else had to do.

This is where a gentleman named Don Dewar comes in. He was a vice-president of director John Ford’s Argosy Productions. He got together with ex Disney artists Jack Boyd and Dick Moores to come up with Telecomics.

Jim Hardy was a newspaper comic strip Moores had been drawing. The

Los Angeles Times of March 29, 1950 advertised the debut of its local TV counterpart. The ad includes the word “Telecomics.” The cartoon show was a mere five minutes.

Then the Telecomics found a network buyer.

Daily Variety reported on August 7, 1950 that NBC had purchased them, and would air them in a 15-minute block.

NBC Comics debuted on September 18, 1950, appearing from 5 to 5:15 p.m. Monday through Friday. By mid-November, Standard Brands sponsored the Thursday broadcasts. That seems to have given the cartoon show a bit of publicity.

Walter Ames of the Los Angeles

Times had this to say in his column of November 20th:

The other day I was invited by Don Dewar, president of Tele-comics, Inc., to watch a showing of the new NBC Comics series and I came away with the thought that maybe it was the answer to many mothers' pleas for something to drag their children away from the westerns now flooding the television screens.

Don told me he and his three partners, Jack Boyd and Dick Moores started working on the idea several years ago and have been experimenting with the Jim Hardy series seen nightly on KLAC. Their present comics consist of Danny March, a private investigator; Space Barton, for the outer world minded offspring, and Kid Champion, for the rugged characters. Also included is the daily lesson on righteousness by Johnny and his dog, Mr. Do Right.

They are not animated but the pace at which the narration is carried and the action packed drawings make you forget this small item. As Don pointed out animations" of humans are unsatisfactory from a viewing point. So tonight, insist on the kids watching the first episodes of the NBC Comics on KNBH (4) at 5:15. I think they might solve some problems.

Billboard’s June Bundy reviewed the series in the magazine’s edition of November 15, 1950.

The NBC Comics is an experiment in low-budget video programing for children that doesn’t quite jell entertainment-wise. The idea of screening a series of comic drawings in close-ups, a la comic strip panels in newspapers, probably looked good on paper, but it’s slow-paced and difficult to follow on TV.

Instead of the balloon-dialog used in funny papers, the show has live talent read the lines off camera while mum’s the word on screen. Maybe the kiddies have faster reflexes, but this reviewer found it rough going trying to tell the Martians from the earthlings. The dialog often seemed to have no relation to the drawings and, at times, the whole thing took on the eerie aspect of a comic strip Strange Interlude. It was even harder to “tell the players without a program” when the producers economized, via long shots of several characters in silhouette.

In addition to the science fiction hero Barton, this program featured Kid Champion, a prize fighter resembling Joe Palooka, and a brief educational bit tagged Johnny and Mr. Do Right. The latter, which preached the golden rule, “Always cover your mouth before coughing or sneezing,” was the best of the lot.

The commercials featured a sheepish grown-up emsee wearing a paper crown and looking like a fugitive from an audience participation show.

After several appetizing shots of Royal Pudding deserts [sic], he gave a big pitch for Standard Brands’ premium photo gimmick. The plug was strengthened when a freckle-faced young boy showed off his own collection of Royal’s movie and sports starts pictures.

aired for the last time on March 30, 1951. It was replaced by the soap opera

Hawkins Falls, brought to you by No-Rinse Surf. One trade paper noted Lever Brothers bought the soap on February 13th with the idea of eventually taking the kids show slot.

Variety on May 30, 1951 reported Dewar was in New York with a first print of a new series which actually had a little more animation to it. There were no takers. Dewar and Boyd took over Moores’ interest in August. By then, the company was called Illustrate.

But this wasn’t the end of

NBC Comics. Now that the cartoons were off the network, they could be syndicated.

Variety of June 8, 1951 reported:

KTSL, on Monday, begins airing 13 first-run telecomics cartoon strips. The 15-minute, five-a-week juvenile-appeal show formerly aired on KNBH as "NBC Comics."

First 13 strips are first run; the rest will be second run of those aired over KNBH.

Figuring out 1950s TV syndication rights is a nightmare. Companies opened, closed, morphed, consolidated and formed multiple subsidiaries. At the start of 1954, they were in the library of Flamingo Films. When a couple of Flamingo executives moved over to NTA, the TeleComics came over as well. NTA, you may remember, syndicated some of the cartoons originally made by the Fleischers.

The

TeleComics had some longevity. Channel 9 in Dothan, Alabama was broadcasting them in 1959 when they must have looked particularly shoddy.

The

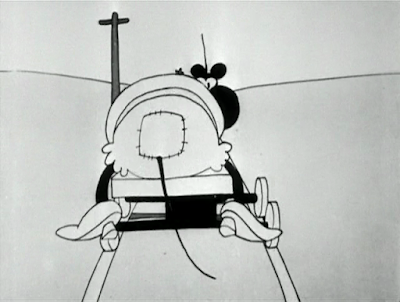

Billboard review above indicates what the problem was. The cartoons really weren’t animated. They were panel drawings over narration, and visually uninteresting panel drawings, too. There was no attempt to render something like Prince Valiant or Terry and the Pirates on the Sunday comic page. For example, Johnny Do-Right, the behavioural propaganda cartoon with Verne Smith speaking over top, had drawings that only got as elaborate as this.

Danny March.

Kid Champion.

And Space Barton!

A few

NBC/

Tele- Comics are on the web; they’re from 16mm reels that someone rescued. You can learn more about them in

this post and

this post. I imagine this blog has given these poor old cartoons more attention than they got when they first aired.