Would you believe 1928?

Yes, that was the year WGY, your friendly General Electric radio station in Schenectady, New York, decided the time was ripe to beam telecasts into homes on a regular basis. Only there really wasn’t much programming in those days.

On January 13, 1928, WGY made what it said was the first televised broadcast into people’s homes. Three of them to be precise. Newspapers raved about the picture that came through the 3 inch-by 3 inch screen, but it couldn’t have been that terrific. The New York Times reported the programming consisted of a man (Leslie Wilkins) smoking and another man (Louis Dean) playing a ukulele. The New York Herald Tribune said it was a woman smoking and a man playing a banjo. The Schenectady Gazette was silent on the genders of the performers and only stated that instruments were played.

Nevertheless, WGY continued with its experimental broadcasts, with the picture on 37.8 metres and the sound on 379.5 metres (790 kilocycles). Reported the Times on May 11, 1928:

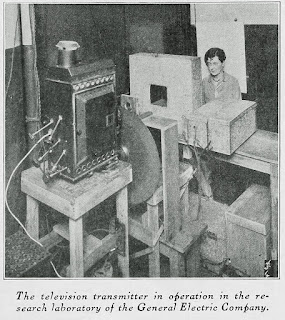

WGY TODAY TO START TELEVISION PROGRAMSRadio magazines keenly followed television with in-depth articles and ads from companies with the materials needed to build your very own set at home. This was the era of mechanical television. That meant a scanning wheel at a studio transmitted the images to peoples’ homes; at WGY, the wheel scanned 24 lines, 20 times a second. Not exactly high-def. But it was a miracle for 1928.

General Electric Company Will Broadcast Pictures Three Times a Week

The General Electric Company will start this afternoon a regular schedule of television broadcasting for the benefit of experiments and amateurs who have constructed television sets. Between 1:30 and 2 P. M. Eastern Daylight Time, it will send pictures from its laboratories in Schenectady over WGY, according to Martin P. Rice, manager of broadcasting. Hereafter on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays at the same time WGY will broadcast for television sets.

Faces of men talking, laughing or smoking will be broadcast today. No elaborate effects will be attempted in the near future.

WGY broadcast television a few minutes last night so that listener[s] might recognize the peculiar sounds which accompany the transmission of pictures by radio. The signal is an intermittent, high-pitched whirr, the pitch varying with the action before the transmitter.

The regular schedule is designed primarily to assist engineers in the development of a reliable and complete system of television, but is expected that radio amateurs may contribute something to the new art.

So how many amateurs with home-built sets caught the first, regularly scheduled TV programme? None. At least that WGY knew about. Here’s the Times again, part of a story from May 20th:

TELEVISION WAVES PASS UNNOTICEDWGY continued with its thrice-a-week schedule, occasionally adding other TV broadcasts. In late August, the station was hailed for airing Al Smith’s acceptance speech for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Then on September 11th, it broadcast what was claimed to be the first televised drama, a two-person play called “The Queen's Messenger” with Izetta Jewel and the English-born Maurice Randall as the characters and Joyce Evans Rector and William J. Toniski as their hands. Meanwhile, WRNY finally got its TV casts on the air in August, broadcasting an extensive schedule of visual shows during the day.

No One Reports Seeing Images Broadcast by WGY—Sale of Aluminum and Neon Lamps Reveals Great Activity in Boston

THE first week of television broadcasts from WGY, Schenectady, N.Y., have traveled off into the infinite without the slightest notice, according to a representative of the station. No one has reported reception of the moving images that have been wafted into space from the Mohawk Valley during the past week.

“Our plans to broadcast television appear to have made a hit, but so far no one has reported picking up the signals,” said a representative of WGY. “Boston has been most active in television plans. We have learned that more than 2,000 pounds of sheet aluminum have been sold there in the past few weeks for revolving discs, and several thousand neon lamps have been sold. We, of course, have received many requests for information on the building of television sets.”

Experimenters Are Active.

Radio amateur experimenters are displaying astonishing interest in television, and the reception of pictures by radio, according to the mail being received by the General Electric Company, at Schenectady, N.Y. The pleas from amateurs that WGY broadcast moving images instead of still pictures led to the decision to adopt a regular schedule for radio motion picture broadcasts on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, between 1:30 and 2 P.M., Eastern Daylight Saving Time. The 380-meter wave is used.

To the few who have television receivers motion pictures will appear. To the millions using standard broadcast receivers tuned to the 380-meter channel the ether wave carrying moving images sounds like howls, squeals and a series of clicks.

“The interest on the part of amateurs in television is astonishing,” said the WGY representative. “We have received hundreds of letters asking for our television schedule, which up to the present time, has been irregular. The amateurs ask that we give them something to work with, so we selected a fixed schedule. It’s anybody’s opportunity now. We have also received many letters asking where a certain type of neon lamp could be purchased, because it is the heart of the television receiver. Now that we have adopted a regular time for television broadcasts it will help us continue our own work, because a stage of development has been reached where a fixed schedule will aid our research engineers.

“I want to make it clear that these early television pictures will not be masterpieces. But no matter what we put on the air, the television experimenters at this stage of the development will not be too critical. They must not expect a fine picture. They should be happy just to catch a glimpse of a moving image, whether it be a research engineer, a pretty girl, a horse or a camel. The nature of the picture should make no difference.” He said the television broadcasts were merely intended to give greater scope to the experimental field. He said no idea existed at Schenectady when television receivers would be placed on the market for the public.

WRNY Plans Tests.

Station WRNY, operating on the 326-meter channel, is scheduled to begin a series of television tests on June 10, based upon a system developed by T.H. Nakken, President of the Nakken Television Corporation of Brooklyn, N.Y.

Mr. Nakken said that his plan is to introduce a system of television that can be used by any broadcasting station under present conditions; that is, when the waves are not more than ten kilocycle apart. If a wider ethereal band could be used, he said that the images might be more pleasant to look at, but today the air is so overcrowded with stations that a suitable wave band is not available for television. This presents one disadvantage in the fact that there is likely to be a slight flicker as one image leaves the screen and the next begins. This limitation can be eliminated as soon as a wider band is made available for television broadcasts, according to Mr. Nakken.

Federal Radio Commissioner O.H. Caldwell has sounded the warning that television will sooner or later face the inescapable fact that “our varied radio services tap and utilize only a single great common conductor, the ether, and that the places in this radio spectrum are numbered and rigidly limited. Thus television by radio—the supreme achievement of the science of communication—may, when generally made available, find itself stifled by the very number and tenacity of its predecessors in the radio field.

Both carried on with their regular TV broadcasts until the end of March 1929. The stations were plagued mainly with regulatory problems. The F.R.C. first ordered WGY to sign off early to protect KGO’s signal from Oakland then demanded all television activity on radio frequencies cease on January 1, 1929 because of the interference it caused other stations. WGY got a judge to put the order on hold, as the new NBC red network took up more and more of its schedule. Meanwhile, WRNY sank deeper and deeper into debt and was finally auctioned (with other assets of its parent company) for $90,000.

WGY-TV left the radio band, but that didn’t end General Electric’s television experiments in Scheneectady. And when commercial broadcasting was allowed in 1941, the station, known as W2XB by then, received a commercial license as WRGB the following year. It’s still on the air today.