The piano exacts its revenge. Look! Another butt attack joke. Walt loved those. I swear there was one in every Disney cartoon for a while.

The animation is credited to the great Ub Iwerks.

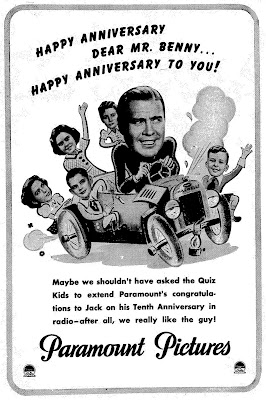

Pinto Colvig and His Trade Are Odd Even for HollywoodWe mentioned network radio at the top of this post. Pinto Colvig’s career intersected with that as well. He played Jack Benny’s Maxwell before Mel Blanc. Read about it in this post.

Special to The Christian Science Monitor

Hollywood, Calif.

Pinto Colvig, and Pinto’s trade, are two of the most curious things Hollywood has ever produced. The tools of Mr. Colvig’s trade consist of two old pie tins, a hand vacuum cleaner, two water buckets, two laundry plungers, a battered old clarinet and a battered old set of drums, some 50 or 60 other miscellaneous musical instruments, including a jew’s harp, hand organ and ocarina, and an array of penny whistles that might make a unit for a museum.

But first, an introduction to Pinto. He began on the vaudeville stage, was graduated to cartooning, went with a circus, and landed in films when he made one of the earliest animated cartoons, “Pinto’s Prisma Comedies.” He gave up drawing cartoons, however, when he discovered his greater value to them. Without much effort, and without any outside aid, Pinto could—and did—imitate practically any natural sound and give it an added fillip that made it immediately and irresistibly funny.

He has moved over now to the Metro studios to work on the new cartoon there, “The Captain and the Kids,” from the famous comic strip, which this company will shortly release; but he was for years with Disney, and was the originator and operator of all sounds made by that third little pig in the saga of that triumvirate.

He can imitate a fish, in or out of water, a fly, a beetle, a frog, a bird, a wagon wheel, an old motor or almost anything else you can name that emits sound. Of course, like all artists, he strives to avoid direct imitation and achieve something approximating and interpretation, and it is just in this process that the fun emerges, and audiences just “naturally” laugh.

Makes Sounds First

His job now has progressed to the point where he doesn’t have to look at the drawings of the animators first to determine what sort of sounds he is going to make. He makes his sounds first now, and the animators do their best to draw something to fit them. But there was a time, of course, when the longer, harder method had to be employed.

He remembers he most difficult imitation as that of a very small bug which was to be ground under an auto tire in one of Disney’s cartoons. The bug was not to like the procedure, and was to protest with a loud bug noise. Pinto tried for days to create that bug’s noise, but without success. Then one day, having all but given up hope, he heard one of his five children making a peculiar noise with a little paper whistle, and realized in a flash that he had his noise. The paper whistle had been obtained in a package of confections, so Pinto bought up a number of boxes of the stuff, but found no whistles. He wrote to the factory—he doesn’t say, but there is a suspicion here that he hadn’t been very successful in his attempts to get the whistle from the child—and the president’s secretary wrote back to say that the whistles weren’t being made any more. She had, however, after searching the whole plant, discovered three of them in the advertising manager’s desk, and she sent them along. Today, they are Pinto’s most prized possessions.

Pinto writes his score in over the regular staffs for the musical score on all cartoons. Over a prettily sentimental bit of music, for example, he may indicate the need for a “kazoo grunt and a dull thud flam,” or a “wet plop,” or for just a “lightly squash and hit iron thud.” These words don’t mean anything to anyone else, but they are Pinto’s language for his sounds.

He is, incidentally, only one of quite a number of people who earn comfortable livings making sounds for animated cartoons. They are Commedia dell’ Arte behind the scenes, hidden pagliacci whose laughs and tears and other curious sounds are clothed in little moving drawings on the screen.

Metro’s Cartoon Plant

The new cartoon plant at Metro, of which Pinto is only a unit, is not uninteresting on its own account. Here labor some 200 people of various trades and arts whose only object is to give pleasure. “Writers” draw their “story” on some 50 or 60 squares of paper, under the supervision of a “director,” who knows both drawing and dramatic and comic story values. Once the story is approved, it is given to the animators, who draw key figures and their key positions, then pass their drawings to “in-between” men, who draw in all the action on many additional squares of paper. Girls ink these drawings on celluloid, and paint the backs of the celluloids with opaque paints.

When all this has been completed, the celluloids are given to the cameraman, who painstakingly shoots them one at a time. If each celluloid were photographed once, it would take 25,000 to 45,000 drawings to make a 700-foot picture. But as many of them are used several times over, in different “repeat” combinations, it usually takes a mere 10,000 to 15,000 for a reel of picture.