Remember how someone got the bright idea to make a live-action version of “Underdog” with a real dog? It came out in 2007, was panned and bombed.

The producers could have avoided all that had they listened to the man who inspired the name of another cartoon character.

Peter Piech was the executive producer of the original Underdog TV cartoons through his part-ownership in Total Television Productions. Prior to that, he was president of Producers Associates of Television, which handled distribution of “Rocky and His Friends,” and had an interest in Gamma Productions, the cartoon studio where “Underdog” and a good percentage of “Rocky” were animated.

Here’s Piech talking about Underdog in this unbylined feature story published in the Rome Daily Sentinel, March 19, 1965. Underdog had debuted the previous October. We can only imagine what the late Alex Anderson would think of Piech getting credit for Rocky being “among his creations.” About the closest he got to creating anything on that show is the character of Peter “Wrong Way” Peachfuzz, whose name—not coincidentally—is close to a certain producer’s. And we’d like to know more about those Farmer Brown cartoons he talked about.

‘Underdog’ Creator Says Children Tough Audience; Not Easily Fooled

"There is no set pattern or guideline for writing humor for children, particularly in cartoons. The only thing we are concerned about is producing a good cartoon sequence.”

The man who made this statement is Peter Piech, executive producer of the color cartoon series, “Underdog” seen Saturdays, at 10 a. m.

One of the most experienced men in cartoon production, Pete has produced approximately 3,000 minutes of cartoons since 1959, more, he claims, than any other animation studio in the world. Among his creations are “Rocky,” “Tennessee Tuxedo,” “Leonardo the Lion,” “The Hunter,” and “Go Go Gophers.”

Pete believes that both children and adults are fascinated by the supernatural and super powers; “Underdog” fits into both of these categories because of his super abilities and the supernatural powers of his enemies.

While he feels that there are no guidelines for writing humor for children, Piech is quick to add that there are definite elements that a cartoon should have to capture their interest and imagination.

“Children are paradoxical in that they are captivated by both the familiar and the unknown,” says Pete. “They know, for instance, that Underdog is always going to catch the bad guy and bring him to justice in the end.

"They also know that he is going to rescue the heroine, Polly, from the teeth of a whirling circular saw or from the beam of villain Simon Barsinister's snow gun. The fact that they know this doesn't make the final rescue any less exciting.”

Kids love repetition, according to Piech, “but a producer can't just come up with one formula and then keep using it indefinitely.”

Pete also maintains that children appreciate the same elements of humor that make adults laugh.

They love Wally Cox as the voice of Underdog because it is very comical to hear such a meek voice coming from such a super-powered hero. They also like the unexpected situation that pops up, and this too is an element in all forms of humor.

Says Piech, “Children today are much more sophisticated than they used to be, and demand more from cartoons than they used to, because they want to use their knowledge more.

It's no longer enough, to give them a ‘Felix the Cat’ or a ‘Farmer Brown’ musical cartoon with singing flowers and cows that kick over milk buckets.

“Today's kids are science-oriented and they want to use their knowledge. They can do this while watching Underdog fight the underwater Bobble-Heads and their tidal wave machine, but they can't if all they see is Felix trying to catch a mouse.”

Pete is adamant in his feelings that there are many topics that cannot be animated, and anything that can be done using live actors and live situations should not be done in cartoon form. In cartoons, everything is much bigger than life, very exaggerated.

"Can you imagine Underdog being played by a real dog, like Lassie?” asks Pete. “It would be impossible!

“And it would be just as ridiculous if Mr. Novak was a cartoon instead of a live person.”

Well, Mr. Piech is being a little disingenuous about “Mr. Novak.” It wouldn’t work in animation in 1965 because it was a drama; cartoons were still pretty much comedies then. But he makes valid points elsewhere in the interview.

If you want to learn the whole story behind the “Underdog” show, you can do no better than read Mark Arnold’s book Created and Produced by Total Television Productions. Check out more here.

Saturday, 6 June 2015

Friday, 5 June 2015

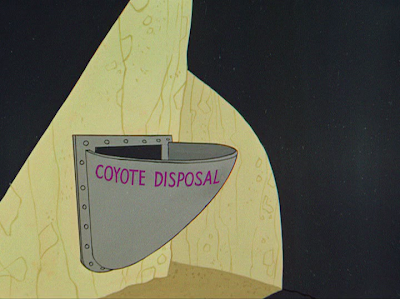

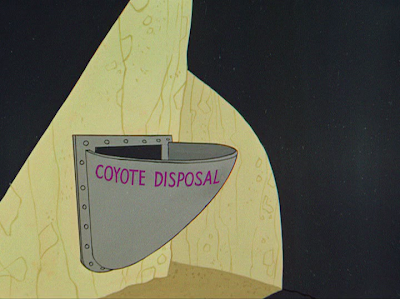

To Hare Is Human Backgrounds

Phil De Guard painted from Maurice Noble’s layouts in “To Hare Is Human,” a 1956 Warners cartoon from the Chuck Jones unit. I can’t get a clear shot of Bugs Bunny’s bed with the carrot-shaped posts but here are some other backgrounds.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Critics claim Jones starting making Bugs far too self-satisfied and flouncy. You might detect some of that in this cartoon.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Critics claim Jones starting making Bugs far too self-satisfied and flouncy. You might detect some of that in this cartoon.

Thursday, 4 June 2015

A 1938 TV Set

Yes, there was television in the 1930s. In 1938, New York City was the home of NBC’s W2XBS. It had also been the home of the Terrytoons studio a few years earlier. So it’s not a surprise Terry and his story department tossed in a TV gag in the short “Bugs Beetle and His Orchestra” released that year.

The evil spider is awoken by the NBC chimes and tunes in his set.

.png)

He spots a luscious female bug. He kisses where she is on his set.

.png)

Her boy-friend bug violates the confines of the TV set and slugs him.

.png)

The angry beetle cracks his TV screen in response.

.png)

Whether this is the first TV gag in a cartoon, I don’t know, but it must be one of the earliest.

Fittingly, when W2XBS began somewhat regular programming in 1939, it featured Terrytoons.

The evil spider is awoken by the NBC chimes and tunes in his set.

.png)

He spots a luscious female bug. He kisses where she is on his set.

.png)

Her boy-friend bug violates the confines of the TV set and slugs him.

.png)

The angry beetle cracks his TV screen in response.

.png)

Whether this is the first TV gag in a cartoon, I don’t know, but it must be one of the earliest.

Fittingly, when W2XBS began somewhat regular programming in 1939, it featured Terrytoons.

Labels:

Terrytoons

Wednesday, 3 June 2015

Aunt Harriet Meets Stanislavsky

She was clueless and a little dithery, but who didn’t love Aunt Harriet?

Madge Blake popped up on TV shows other than “Batman,” but it always seemed a little odd, like she didn’t belong anywhere except Stately Wayne Manor. I guess that’s how strongly I associated Aunt Harriet with her. But Mrs. Blake carved out a nice career, with regular turns on “The Real McCoys,” “The Joey Bishop Show” and occasionally on “Leave It To Beaver.” Maybe her most famous movie role was as the Louella Parsons-esque columnist in the cheery “Singing in the Rain.” But perhaps you didn’t know her acting career came comparatively late in life.

Madge was born Madge Elizabeth Cummings on May 31, 1899 in Kinsley City, Kansas to Albert W. and Alice F. (Stone) Cummings. Blake was her married name; she married J. Lincoln Blake, an interior decorating plant manager (they later divorced). Her father was a minister and didn’t approve of those acting folk. So, as her Associated Press obituary revealed, she waited until he was dead and her kids were grown before embarking on a show-biz career in the late ‘40s.

The only newspaper article I’ve been able to find on her is the one below from a newspaper syndicate, published August 13, 1963.

Woman Past 40 Became Actress

By DAVE McINTYRE

Copley News Service

HOLLYWOOD—Her hair was already beginning to be well-streaked with gray. Two sons were grown and were away from home. In years, she was already well past 40. That’s when Madge Blake decided it would be very nice to get into the movies.

Madge is the delightful woman who spent six years in the cast of “The Real McCoys.” Currently she’s appearing in “A More Perfect Union” at the La Jolla, Calif., Playhouse. Her success as an actress, in movies, television and on the stage, despite her late start, has been remarkable. But don’t for a minute think it was easy.

Miss Blake recalls vividly the comment a director had for her when she first began this quest.

“He asked me point-blank why I didn’t just go home,” she said.

“He told me that I would never be able to make myself heard on stage, that my walk was wrong and my gestures were awkward. He suggested that I not only was wasting my time but the theater’s as well.”

The effect on Miss Blake was not discouragement, however. On the contrary. She vowed she was going to make this particular critic swallow his acid phrases one day. And she did.

This determination had been well honed on other projects. There was the time during the depression when she decided she should have a job. She bombarded the president of a Los Angeles department store with letters until she was hired. And during the war, when her sons were in the service, she felt she should be contributing, so she took a job loading nitroglycerin pellets in rockets.

At the time she set her sights on professional acting, Miss Blake was teaching in a Pasadena, Calif., elementary school. Every night she either worked at the Pasadena Playhouse or at the Glendale Center Theater.

“I knew I had to absorb everything I could,” she said, “because I knew so very little about the theater. I took any role that was offered to me or I worked backstage, just so I could be part of the theater. I read all through Stanislavsky, though I didn’t understand a work of it.”

Once, for example, Madge was given the role of an eccentric English woman in a Noel Coward play at Glendale. She knew nothing about accents, she said, but she found a woman in Pasadena who had recently arrived from England.

“I’ve often thought since how puzzled that woman must have been,” she laughed. “For a time I really cultivated her. I was with her every day, listening to the sound of her voice. Then when I began rehearsing I didn’t see her again and haven’t since.”

The neat revelation in the story is Madge Blake was not a somewhat-addled little old lady like many of her characters on TV. She provides a good example for us all, that ability and determination can help you achieve your goals. In a way, that lesson is as good as anything that we can learn from the Caped Crusader.

Madge Blake popped up on TV shows other than “Batman,” but it always seemed a little odd, like she didn’t belong anywhere except Stately Wayne Manor. I guess that’s how strongly I associated Aunt Harriet with her. But Mrs. Blake carved out a nice career, with regular turns on “The Real McCoys,” “The Joey Bishop Show” and occasionally on “Leave It To Beaver.” Maybe her most famous movie role was as the Louella Parsons-esque columnist in the cheery “Singing in the Rain.” But perhaps you didn’t know her acting career came comparatively late in life.

Madge was born Madge Elizabeth Cummings on May 31, 1899 in Kinsley City, Kansas to Albert W. and Alice F. (Stone) Cummings. Blake was her married name; she married J. Lincoln Blake, an interior decorating plant manager (they later divorced). Her father was a minister and didn’t approve of those acting folk. So, as her Associated Press obituary revealed, she waited until he was dead and her kids were grown before embarking on a show-biz career in the late ‘40s.

The only newspaper article I’ve been able to find on her is the one below from a newspaper syndicate, published August 13, 1963.

Woman Past 40 Became Actress

By DAVE McINTYRE

Copley News Service

HOLLYWOOD—Her hair was already beginning to be well-streaked with gray. Two sons were grown and were away from home. In years, she was already well past 40. That’s when Madge Blake decided it would be very nice to get into the movies.

Madge is the delightful woman who spent six years in the cast of “The Real McCoys.” Currently she’s appearing in “A More Perfect Union” at the La Jolla, Calif., Playhouse. Her success as an actress, in movies, television and on the stage, despite her late start, has been remarkable. But don’t for a minute think it was easy.

Miss Blake recalls vividly the comment a director had for her when she first began this quest.

“He asked me point-blank why I didn’t just go home,” she said.

“He told me that I would never be able to make myself heard on stage, that my walk was wrong and my gestures were awkward. He suggested that I not only was wasting my time but the theater’s as well.”

The effect on Miss Blake was not discouragement, however. On the contrary. She vowed she was going to make this particular critic swallow his acid phrases one day. And she did.

This determination had been well honed on other projects. There was the time during the depression when she decided she should have a job. She bombarded the president of a Los Angeles department store with letters until she was hired. And during the war, when her sons were in the service, she felt she should be contributing, so she took a job loading nitroglycerin pellets in rockets.

At the time she set her sights on professional acting, Miss Blake was teaching in a Pasadena, Calif., elementary school. Every night she either worked at the Pasadena Playhouse or at the Glendale Center Theater.

“I knew I had to absorb everything I could,” she said, “because I knew so very little about the theater. I took any role that was offered to me or I worked backstage, just so I could be part of the theater. I read all through Stanislavsky, though I didn’t understand a work of it.”

Once, for example, Madge was given the role of an eccentric English woman in a Noel Coward play at Glendale. She knew nothing about accents, she said, but she found a woman in Pasadena who had recently arrived from England.

“I’ve often thought since how puzzled that woman must have been,” she laughed. “For a time I really cultivated her. I was with her every day, listening to the sound of her voice. Then when I began rehearsing I didn’t see her again and haven’t since.”

The neat revelation in the story is Madge Blake was not a somewhat-addled little old lady like many of her characters on TV. She provides a good example for us all, that ability and determination can help you achieve your goals. In a way, that lesson is as good as anything that we can learn from the Caped Crusader.

Tuesday, 2 June 2015

Jumbo Gro Works!

‘Jumbo Gro’ does its job in Tex Avery’s fan-favourite “King-Size Canary” (1947). The hobo cat pours it in the little bird (Sara Berner). These are consecutive drawings. Note the squash and stretch on the bird.

The bird grows some more.

And a typical Avery extreme in reaction.

Bob Bentley, Ray Abrams and Walt Clinton are the credited animators.

The bird grows some more.

And a typical Avery extreme in reaction.

Bob Bentley, Ray Abrams and Walt Clinton are the credited animators.

Labels:

King-Size Canary,

MGM,

Tex Avery

Monday, 1 June 2015

Cartoon Stuff Around the Internet

There are plenty of great places on the internet to learn about old cartoons. Other than the blog roll on the side, I don’t link to very many, especially videos because the addresses become dead links more often than I’d like. But there are a few things that have popped up on line during the last week or so that I’ll link to, as you really should check them out.

There are a number of cartoon series I’m not crazy about. One of them is the Tom and Jerry series made by Gene Deitch. There’s no point in making a list of the things I dislike about those shorts. A far better thing, instead, is to read what Mr. Deitch has to say about them. He’s posted about his experiences making them exclusively to Jerry Beck’s aptly-named Cartoon Research site. Read his first-hand insights HERE. (Mr. D. was responsible for some cartoons I quite enjoy. For one, Munro is a fine short).

Incidently, there are Deitch T&J fans who have said to me “Well, they’re better than those Chuck Jones ones,” as if I’m supposed to pick between the two. I’m not a fan of the Jones cartoons, either. If I had a choice, I would pick neither of them. And the Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera version of the cat and mouse had run out of gas by the time production was stopped in 1957.

Something I am a fan of is industrial and commercial cartoons. A neat cartoon is “Winky the Watchman,” a 1945 live action/animation short by Hugh Harman Productions. I’ll take a pass on Harman’s faux Uncle Walt cartoons at MGM of the mid to late ‘30s. But this one I like, mostly because of the animation of the bad guys and some creative layouts. And even better than the cartoon is the fact that Mark Kausler has recorded a commentary that explains, in great detail, all kinds of things about the production that only he would know. Frankly, I’ll listen to any cartoon commentary of Mark’s because I always learn something. Go to THIS POST on Jerry’s blog and read about it. The cartoon and commentary are courtesy of Thunderbean Animation, which is painstakingly restoring all kinds of great old cartoons that would have been forgotten otherwise.

Jerry’s got other great features at Cartoon Research (as if I have to tell you that). Recently, Devon Baxter has been posting (from various sources) breakdowns of animators on various cartoons from official studio documents. And I’m looking forward to Mike Kazaleh returning to give some more thoughts about 1950s TV spots made by the era’s top commercial studios.

Mark Evanier’s News From me blog always has something interesting or funny or both. Recently, Mark posted a link to a bunch of interviews on video with people involved in the Golden Age of cartoons. The sound isn’t great on all of them and I’d have asked some different questions, but at least someone made the effort to talk to these animation veterans. Included are Alex Lovy (of the Lantz and Columbia studios), Lloyd Vaughan, Owen Fitzgerald and Pete Alvarado (all of whom worked at Warner Bros. at one point). They’re worth your time to listen. HERE’s where you can find them, along with some thoughts from Mark who always has something worthwhile to say about cartoons and comics.

There are a number of cartoon series I’m not crazy about. One of them is the Tom and Jerry series made by Gene Deitch. There’s no point in making a list of the things I dislike about those shorts. A far better thing, instead, is to read what Mr. Deitch has to say about them. He’s posted about his experiences making them exclusively to Jerry Beck’s aptly-named Cartoon Research site. Read his first-hand insights HERE. (Mr. D. was responsible for some cartoons I quite enjoy. For one, Munro is a fine short).

Incidently, there are Deitch T&J fans who have said to me “Well, they’re better than those Chuck Jones ones,” as if I’m supposed to pick between the two. I’m not a fan of the Jones cartoons, either. If I had a choice, I would pick neither of them. And the Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera version of the cat and mouse had run out of gas by the time production was stopped in 1957.

Something I am a fan of is industrial and commercial cartoons. A neat cartoon is “Winky the Watchman,” a 1945 live action/animation short by Hugh Harman Productions. I’ll take a pass on Harman’s faux Uncle Walt cartoons at MGM of the mid to late ‘30s. But this one I like, mostly because of the animation of the bad guys and some creative layouts. And even better than the cartoon is the fact that Mark Kausler has recorded a commentary that explains, in great detail, all kinds of things about the production that only he would know. Frankly, I’ll listen to any cartoon commentary of Mark’s because I always learn something. Go to THIS POST on Jerry’s blog and read about it. The cartoon and commentary are courtesy of Thunderbean Animation, which is painstakingly restoring all kinds of great old cartoons that would have been forgotten otherwise.

Jerry’s got other great features at Cartoon Research (as if I have to tell you that). Recently, Devon Baxter has been posting (from various sources) breakdowns of animators on various cartoons from official studio documents. And I’m looking forward to Mike Kazaleh returning to give some more thoughts about 1950s TV spots made by the era’s top commercial studios.

Mark Evanier’s News From me blog always has something interesting or funny or both. Recently, Mark posted a link to a bunch of interviews on video with people involved in the Golden Age of cartoons. The sound isn’t great on all of them and I’d have asked some different questions, but at least someone made the effort to talk to these animation veterans. Included are Alex Lovy (of the Lantz and Columbia studios), Lloyd Vaughan, Owen Fitzgerald and Pete Alvarado (all of whom worked at Warner Bros. at one point). They’re worth your time to listen. HERE’s where you can find them, along with some thoughts from Mark who always has something worthwhile to say about cartoons and comics.

Sunday, 31 May 2015

Betsy Palmer

The last few months haven’t been good ones for fans of the old game show “I’ve Got A Secret.” Within the last six months, three of the ladies who graced the panel have passed away. First, it was Bess Myerson late last year, then Jayne Meadows a little over a month ago, and now Betsy Palmer has died.

Growing up in the ‘60s, it seemed to me that Betsy was one of those people who TV Guide classified as “television personalities.” It meant they made the rounds of game shows and talk shows. They appeared on TV as themselves. They never seemed to do any acting. That wasn’t really the case, but that was the impression I got.

Let’s pass on a couple of clippings from, arguably, Betsy’s heyday in the late ‘50s. Here’s a syndicated column from September 29, 1958. On “I’ve Got A Secret,” Betsy was always upbeat and in good humour. That apparently bothered some TV viewers.

This little piece from November 19, 1953 is the earliest story I can find about her (other than mentions in a gossip column linking her to a TV director). It appears Betsy was the original Vanna White.

Growing up in the ‘60s, it seemed to me that Betsy was one of those people who TV Guide classified as “television personalities.” It meant they made the rounds of game shows and talk shows. They appeared on TV as themselves. They never seemed to do any acting. That wasn’t really the case, but that was the impression I got.

Let’s pass on a couple of clippings from, arguably, Betsy’s heyday in the late ‘50s. Here’s a syndicated column from September 29, 1958. On “I’ve Got A Secret,” Betsy was always upbeat and in good humour. That apparently bothered some TV viewers.

Betsy Palmer Galled ‘Too Happy’This syndicated column appeared in the Niagara Falls Gazette, November 1, 1959. I can’t find it bylined elsewhere on-line, and this version ends very abruptly; I suspect it was longer in other papers.

By STEVEN H. SCHEUER

Betsy Palmer, TV’s answer to the old Happiness Boys of radio, is so cheerful that a few grouches have written to the “Today” show complaining that nobody has any right to be that happy so early in the morning. One disgruntled viewer even went so far as to suggest that what the “Today” show really needs to make it a smashing success is to dispense with Betsy and bring in some people who know how to snarl and act nasty. In that way, reasons the writer, people watching the show will feel right at home.

Betsy, who has to get up a half hour ahead of any normal rooster to get to the show on time, confesses she’s cheerful all day long. “I’M VERY LUCKY,” SHE TOLD ME.

“I’m married to a man who can get up at the same hour I do and be just as cheerful. He’s a doctor. Can you imagine what our married life would be like if either of us woke up grouchy the way so many other people seem to?”

Professionally, Betsy Palmer has every right to be cheerful. She’s probably the workingest actress on TV. In addition to her daily “Today” chores, she’s a regular panelist on “I’ve Got a Secret,” you’ll be seeing her in “The Time of Your Life,” on Oct. 9 (CBS-TV), she makes frequent appearances on such shows as Playhouse 90 and the U. S. Steel Hour, she’s slated for a guest shot on the new Garry Moore Show, and may be yanked off to Hollywood on a moment’s notice to play a leading role in the film version of “The Last Angry Man”.

“I’m also going to be seen in that Doris Day thing,” she added, referring to a picture now called “The Jane From Maine” (and Columbia Pictures ought to be ashamed of that title), formerly known as “Miss Casey Jones”, for which the entire “I’ve Got a Secret” panel filmed a sequence.

Though she’s almost letter per feet on lines, Betsy admits even she makes occasional fluffs. On her most recent U. S. Steel Hour appearance, she red-facedly confessed:

“The line was ‘I phoned the base.’ I improved it. It came out ‘I bored the face.’”

Betsy Palmer Thrilled At Role Opposite MuniThe first TV role I’ve found for her in the New York papers was on April 28, 1952 on WOR-TV’s “Broadway TV Theatre,” where she played Mary Dale in a mounting of “The Jazz Singer,” with Lionel Ames in the role made famous by Al Jolson. 1953 seems to have been her breakthrough year as she landed roles on the big network shows. Her credits: “Studio One,” “Sentence of Death” (supporting with James Dean, Aug. 17); “Danger”, “Death Is My Neighbor” (supporting with James Dean, Aug. 25); “Studio One, “Look Homeward Hayseed” (with Russell Nype, Sept. 7); “Armstrong Circle Theatre,” “A Story to Whisper” (with Leslie Nielsen, Sept. 15); “Studio One,” “Hound Dog Man” (supporting Jackie Cooper, Sept. 28).

HOLLYWOOD — Ever since her appearance with Paul Muni in a short-lived play, titled “Home At Seven” [in November 1953], blonde, brown-eyed Betsy Palmer declares that Mr. Muni is not only one of her favorite actors, but one of her favorite human beings.

Thus, she was delighted when she was cast in Columbia’s Fred Kohlmar production, “The Last Angry Man,” film version of Gerald Green’s best-selling novel, in which Mr. Muni plays Sam Abelman, the dedicated Brooklyn slum doctor. As to producer Kohlmar and director Daniel Mann, Miss Palmer says, “I’m hoping that I’ll soon have another opportunity do work with them; they’re both simply wonderful.”

Married to Doctor

It was just so much more interesting for her to watch Mr. Muni playing the doctor because she herself is well indoctrinated in the medical life, its demands, penalties and rewards; in private life, she's the wife of Dr. Vincent Merindino, whom she met in New York on a blind date, and married after four months of courtship.

In “The Last Angry Man,” Miss Palmer plays the understanding young wife of David Wayne, top-billed with Mr. Muni as the television executive who hopes to put Dr. Abelman on the air as star of his own-life story. This is a straight dramatic role, and one of the many in the playing of which Betsy has been called upon to “just be herself.”

But that isn’t to say that she can’t play—and hasn’t played—many other types. Whether it be a misunderstood wife, a street girl, or a young mother, she delivers, with the talent to make the part convincing.

Laudatory Comment

“When Betsy’s around, things sparkle and look and sound good,” Dave Garroway once said of her. “She’s young, gentle, lovely—and a lady.”

Along with her weekly stint as panelist on “I’ve Got A Secret,” Miss Palmer can usually be found around the studio in any one of the networks, for she is one of the most sought-after young actresses the medium—Playhouse 90, U.S. Steel Hour and many others.

There are no secrets about this girl, who frequently amazes more devious colleagues with her frankness. “Why shouldn’t I admit my age?” says Betsy. “I’m 32. After all, if I’m too young, I might lose out on playing somebody’s mother.”

Jackie Gleason picked her to play the part of Kitty Duval in “The Time Of Your Life,” declaring, “I've watched her on a lot of shows. She’s a fine actress, with a quality that is intangible. She’s adorable; she has a niceness and a sweetness and a wholesomeness that really come across.”

‘Typical’ Girl

Miss Palmer is invariably referred to as “a typical American Girl,” even though she enjoys playing roles that are at variance with that label. Her childhood, she says, was a completely normal and happy one. She was born Patricia Betsy Hrunek — and that isn’t American at all; the name is Czech, and she is proud of her Slavic descent.

The place of her birth was East Chicago, Indiana. Her father was a chemist and her mother operated a successful business school. The youngster went to grade school in East Chicago and Roosevelt High. Then, for a time, planning to become a Girl Scout executive, she attended her mother’s institute of learning, the East Chicago Business College.

She wasn’t exactly a tomboy, but she was something of a cut-up, addicted to practical jokes. Hoping for more discipline, in the life of her ebullient young daughter, Mrs. Hrunek packed her off to DePaul University, where she became Queen of practically everything in the way of campus activities.

This little piece from November 19, 1953 is the earliest story I can find about her (other than mentions in a gossip column linking her to a TV director). It appears Betsy was the original Vanna White.

Betsy Palmer Vetoed Martin and Lewis JobI suppose the 1959 story sums up how many people think of Betsy Palmer today (her role in “Friday the 13th” notwithstanding), the friendly, somewhat bubbly girl-next-door. But my favourite interview with Betsy was a great and funny conversation she had with old comedy chronicler Kliph Nesteroff a few years ago. She’s still somewhat bubbly but isn’t quite the girl-next-door. Read it HERE. Find out if she’s got a secret.

By STEVEN H. SCHEUER

Ever think you’d hear about a television actress turning down the lead in a Martin and Lewis picture? Neither did we until the charming and refreshingly sensible Betsy Palmer confided in us the other day. “I was afraid of being type-cast as a dumb blonde,” blond Betsy explained and proceeded to add that she’d also refused a long-term contract with Hal Wallis, partly because she didn’t want to get tied up for five years. Betsy owes her first major TV break to CBS producer William Dozier, who spotted her at a general audition and promptly gave her a good supporting role a few weeks later. The play was a Studio One production of “The River Garden,” last Spring. Betsy’s outstanding job was soon followed by consistently exciting work on other major dramatic shows, "and by late Summer Betsy was back on Studio One playing a lead. Betsy hastened to add, “I only got the role because Barbara Britton refused the part. I’ve also done commercial pictures and I was on ‘Wheel of Fortune’ where I was a poor man’s Roxanne. That's because I handed out less7 money on the daytime show than that girl R does on the nighttime ‘Break the Bank.’” We don’t think it’s a question of money, Betsy. After all; you can act!

Benny By Vilanch

Jack Benny touched many lives, and the proof was in the seemingly countless eulogies in newspapers across North America after his death in 1974. It seemed everyone had some kind of personal story, either from meeting Jack or through his weekly appearances in living rooms via a box with tubes and dials.

One remembrance was written by Bruce Vilanch. He’s known today for a number of things, including gag writing for the Oscar telecast, but at the time of Benny’s death, he was a writer for the Chicago Tribune. That’s where this story appeared on December 31, 1974.

Remembering a 'tightwad' who enriched our lives

ONE OF THE EARLIEST television memories among members of my generation is the vision of Jack Benny.

Just standing there, one arm across the chest, the hand clutching the opposite elbow, the fingers placed pensively on the cheek, looking for all the world like somebody who has just had his foot run over by a Prussian regiment that he just found leaving his bathroom.

Eternally perplexed, forever befuddled, Benny mastered the art of letting everything go on around him and only then making you laugh by his reaction. He was the king of the slow burn, the absolute ruler of the throwaway line or ges- ture. He was funnier standing still than any 10 comics on the hoof.

UNLIKE MOST other people who are writing about him now, I never really knew Benny. I interviewed him once-in the middle of a Mill Run engagement that had him more perplexed than usual because he was working on a stage that wouldn't stop twirling, and it kept distracting him. At the time, he was chuckling over an offer he had just received from David Merrick.

"He wants me to play 'Hello, Dolly!' in drag," Benny said, with a half-ironic smile on his face. After we had finished laughing, he quietly added, "Of course, I'll do it ... but only if he lets George Burns play Horace."

The Benny-Burns practical joking was one of the longest-running merry pranks in show business and, toward the end, when Benny was making most of his impact on talk shows, it had achieved legendary proportions.

My own favorite story was the one about Benny and Burns at a big party. Benny was standing silently in a corner of the room, just about to light up a cigar. Suddenly, from across the room, Burns called out In a loud voice, "Stop! Everybody stop! Jack Benny is going to do the match bit!"

OF COURSE, there was no match bit. Benny just stood there, holding the lighted match and the cigar, as 100 Hollywood eyes bore down upon him, waiting to be doubled over by his trick.

"So what could I do?," he later related, "I just turned on my heel and walked out of the room."

The crowd roared.

Of course, there was much more to Jack Benny than his slow burns or his George Burns. He knew timing like no one else, he knew story-telling like no one else, he knew silence like no one else. He was as funny without words, sometimes even without gestures, as anyone ever has been.

More than that, tho, he knew how to make fun of himself in a way that few performers ever figure out.

LIKE LIBERACE, who anticipates the audience's mild outrage at his manners and dress and, therefore, comes on in the brightest sequins imaginable, with a joke to match, Benny understood his myth and wasn't abashed by it.

They said he was a tightwad, and he joked about it, but outrageously. I'll never forget one of his early television shows, where he had to get the money out of the vault in order to repair the Maxwell which, after 135 years of service, had finally broken down.

"Just a minute," he said to Rochester, "I'll be right back." And he then led us on a half-hour descent to the sub-sub basement of his home where, in order to reach the money, he had to cross a moat filed with alligators, an elaborate booby-trapping system, and finally a 200-year-old man, covered with cobwebs, standing poised next to the vault, a bow and arrow at the ready.

You don't run across this sort of self-placed humor any more. Maybe it's because comedians today aren't as self-defined as Benny, or maybe it's because, in the new age of fear and loathing, no one intentionally sets himself up as a fool.

Whatever the reasons, we won't be seeing anything like Jack Benny ever again-they don't make 'em that brave anymore.

HOLDUP MAN-Your money or your life!

BENNY-[silence].

HOLDUP MAN-I said your money or your life!

BENNY-[a shout] I'm thinking it over!

Oh, Rochester. Get him his blue suit.

One remembrance was written by Bruce Vilanch. He’s known today for a number of things, including gag writing for the Oscar telecast, but at the time of Benny’s death, he was a writer for the Chicago Tribune. That’s where this story appeared on December 31, 1974.

Remembering a 'tightwad' who enriched our lives

ONE OF THE EARLIEST television memories among members of my generation is the vision of Jack Benny.

Just standing there, one arm across the chest, the hand clutching the opposite elbow, the fingers placed pensively on the cheek, looking for all the world like somebody who has just had his foot run over by a Prussian regiment that he just found leaving his bathroom.

Eternally perplexed, forever befuddled, Benny mastered the art of letting everything go on around him and only then making you laugh by his reaction. He was the king of the slow burn, the absolute ruler of the throwaway line or ges- ture. He was funnier standing still than any 10 comics on the hoof.

UNLIKE MOST other people who are writing about him now, I never really knew Benny. I interviewed him once-in the middle of a Mill Run engagement that had him more perplexed than usual because he was working on a stage that wouldn't stop twirling, and it kept distracting him. At the time, he was chuckling over an offer he had just received from David Merrick.

"He wants me to play 'Hello, Dolly!' in drag," Benny said, with a half-ironic smile on his face. After we had finished laughing, he quietly added, "Of course, I'll do it ... but only if he lets George Burns play Horace."

The Benny-Burns practical joking was one of the longest-running merry pranks in show business and, toward the end, when Benny was making most of his impact on talk shows, it had achieved legendary proportions.

My own favorite story was the one about Benny and Burns at a big party. Benny was standing silently in a corner of the room, just about to light up a cigar. Suddenly, from across the room, Burns called out In a loud voice, "Stop! Everybody stop! Jack Benny is going to do the match bit!"

OF COURSE, there was no match bit. Benny just stood there, holding the lighted match and the cigar, as 100 Hollywood eyes bore down upon him, waiting to be doubled over by his trick.

"So what could I do?," he later related, "I just turned on my heel and walked out of the room."

The crowd roared.

Of course, there was much more to Jack Benny than his slow burns or his George Burns. He knew timing like no one else, he knew story-telling like no one else, he knew silence like no one else. He was as funny without words, sometimes even without gestures, as anyone ever has been.

More than that, tho, he knew how to make fun of himself in a way that few performers ever figure out.

LIKE LIBERACE, who anticipates the audience's mild outrage at his manners and dress and, therefore, comes on in the brightest sequins imaginable, with a joke to match, Benny understood his myth and wasn't abashed by it.

They said he was a tightwad, and he joked about it, but outrageously. I'll never forget one of his early television shows, where he had to get the money out of the vault in order to repair the Maxwell which, after 135 years of service, had finally broken down.

"Just a minute," he said to Rochester, "I'll be right back." And he then led us on a half-hour descent to the sub-sub basement of his home where, in order to reach the money, he had to cross a moat filed with alligators, an elaborate booby-trapping system, and finally a 200-year-old man, covered with cobwebs, standing poised next to the vault, a bow and arrow at the ready.

You don't run across this sort of self-placed humor any more. Maybe it's because comedians today aren't as self-defined as Benny, or maybe it's because, in the new age of fear and loathing, no one intentionally sets himself up as a fool.

Whatever the reasons, we won't be seeing anything like Jack Benny ever again-they don't make 'em that brave anymore.

HOLDUP MAN-Your money or your life!

BENNY-[silence].

HOLDUP MAN-I said your money or your life!

BENNY-[a shout] I'm thinking it over!

Oh, Rochester. Get him his blue suit.

Labels:

Jack Benny

Saturday, 30 May 2015

Woody in Vietnam

Gracie Lantz has always reminded me of an older neighbour down the street who would give cookies and hot chocolate to the local kids if they dropped over to see her. She and her husband Walter have always come across as nice people. So it’s pleasing to read they took the time to go overseas to meet with troops engaged in the Vietnam War.

Here’s an Associated Press story from January 18, 1970.

Woody Woodpecker Hit With Wounded GIs

By GENE HANDSAKER

HOLLYWOOD (AP) — Woody Woodpecker, a brash bird with a tassel top and a raucous cackle, scored a triumph with 5,600 GIs wounded in Vietnam.

Woody's creator, Walter Lantz, and Walter's wife Gracie, Woody's voice, have returned from visiting military hospitals in the Far East.

Woody Real Star

The Lantzes aside, Woody was the star. Lantz made 3,500 Woody Woodpecker sketches for patients — about 250 of them on plaster casts — and Gracie did the voice "thousands of times." Said Lantz: "It's the most gratifying thing we've ever done."

This was one of the USO's "handshake tours" to brighten hospital life for the wounded. Gypsy Rose Lee, Leif Erickson, Sebastian Cabot and others preceded the Lantzes.

Vet Performers

The Lantzes, who claim a combined century in show business, are one of Hollywood's liveliest couples. The craggy-faced, raspy-voiced Walter, now in his 28th year of producing Woody Woodpecker animated cartoons, is 69. The warm-hearted, outgoing former Grace Stafford, actress and onetime vaudevillian, is 66.

"Hi, fellas," Walter would say, entering a hospital ward on the trip. "I'm Walter Lantz. This is Gracie, my wife, the voice of Woody Woodpecker, We're here from Hollywood just to shake your hands and let you know we're thinking about you."

Record Laugh

The patients asked about cartoon-making, joked with the stars and requested endless repetitions of Woody's cackle.

Some patients tape-recorded the bird's laugh, and one said he'd blast it back at 4 a.m. "to shake up the doctors."

In 31 days the Lantzes traveled 20,000 miles and visited hospitals in Japan, Korea, Okinawa, the Philippines and Guam.

One of the nicest legacies the Lantzes could have left (Grace died in 1992, Walter in 1994) was to bequeath mounds of production material and film to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, where fans can study the Lantz cartoons (ah, if only it was on-line for those of us nowhere near Los Angeles). And the Walter Lantz Foundation is still around providing sizeable grants to advance the art of animation. Walter and Gracie are still doing good today.

Here’s an Associated Press story from January 18, 1970.

Woody Woodpecker Hit With Wounded GIs

By GENE HANDSAKER

HOLLYWOOD (AP) — Woody Woodpecker, a brash bird with a tassel top and a raucous cackle, scored a triumph with 5,600 GIs wounded in Vietnam.

Woody's creator, Walter Lantz, and Walter's wife Gracie, Woody's voice, have returned from visiting military hospitals in the Far East.

Woody Real Star

The Lantzes aside, Woody was the star. Lantz made 3,500 Woody Woodpecker sketches for patients — about 250 of them on plaster casts — and Gracie did the voice "thousands of times." Said Lantz: "It's the most gratifying thing we've ever done."

This was one of the USO's "handshake tours" to brighten hospital life for the wounded. Gypsy Rose Lee, Leif Erickson, Sebastian Cabot and others preceded the Lantzes.

Vet Performers

The Lantzes, who claim a combined century in show business, are one of Hollywood's liveliest couples. The craggy-faced, raspy-voiced Walter, now in his 28th year of producing Woody Woodpecker animated cartoons, is 69. The warm-hearted, outgoing former Grace Stafford, actress and onetime vaudevillian, is 66.

"Hi, fellas," Walter would say, entering a hospital ward on the trip. "I'm Walter Lantz. This is Gracie, my wife, the voice of Woody Woodpecker, We're here from Hollywood just to shake your hands and let you know we're thinking about you."

Record Laugh

The patients asked about cartoon-making, joked with the stars and requested endless repetitions of Woody's cackle.

Some patients tape-recorded the bird's laugh, and one said he'd blast it back at 4 a.m. "to shake up the doctors."

In 31 days the Lantzes traveled 20,000 miles and visited hospitals in Japan, Korea, Okinawa, the Philippines and Guam.

One of the nicest legacies the Lantzes could have left (Grace died in 1992, Walter in 1994) was to bequeath mounds of production material and film to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, where fans can study the Lantz cartoons (ah, if only it was on-line for those of us nowhere near Los Angeles). And the Walter Lantz Foundation is still around providing sizeable grants to advance the art of animation. Walter and Gracie are still doing good today.

Labels:

Walter Lantz

Friday, 29 May 2015

The Eyes of Bleep

Colonel Bleep cartoons are more a curiosity than anything. The narration is strictly for kids and not very amusing. The interesting thing is watching how the people at the Soundac studio in Miami handled extreme limited animation. Some of the movement is pretty creative.

Here’s where the Colonel winks his eyes. The camera moves in. He closes his eyes and when he opens them again, a spaceship in distress appears in them.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

The Colonel, Squeak and Scratch were first syndicated in mid-1957, pre-dating Ruff and Reddy in the made-for-TV-cartoon calendar of milestones.

Here’s where the Colonel winks his eyes. The camera moves in. He closes his eyes and when he opens them again, a spaceship in distress appears in them.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

The Colonel, Squeak and Scratch were first syndicated in mid-1957, pre-dating Ruff and Reddy in the made-for-TV-cartoon calendar of milestones.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)