Betty BoopThe reviewer didn’t seem to want Betty in a cartoon unless she was dealing with letches coming onto her as inanimate objects sprung to life for little bits of odd business. This cartoon’s in the Disney vein. But using a one-shot female character instead of Betty just wouldn’t have worked. And when you’re using colour for the first time, wouldn’t you showcase your star?

“Poor Cinderella”

10 Mins.

Paramount, N. Y.

Paramount

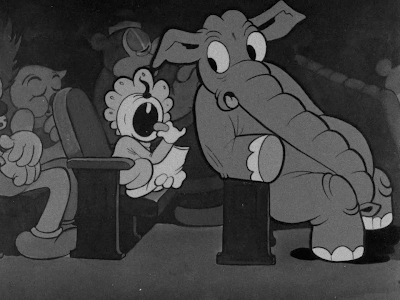

Color cartoon by the new process with firm tones and practically no bleeding, but a lack of tints in the colors. Conventional story of Cinderella other than that Cindy is Betty Boop at her boopiest. Good stuff for the children around holiday times and carrying a catchy melody for a theme song, but not the knockout it was intended to be chiefly because the main character is unsuitable. Sound very poor. Chic.

I’m very surprised the reviewer didn’t mention the 3-D effects during the short which are spectacular. Here are the background drawings from when Cinderella runs away after the clock strikes 12.

.png)

.png)

.png)

After the transformation, the scene changes from the ragged Cinderella to the prince in the palace (who sounds like he read his lines from the back of the room). The transition from one scene to the next involves a setting swirling behind the animation. Here’s one complete turn.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Seymour Kneitel was the head animator on this short.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)