Sid Chatton, CKMX announcer an[d] impersonator of voices of screen and radio players, has joined Don Lee network.It piqued my interest because there couldn’t have been many impressionists on local Canadian radio at the time, and Chatton was among a string of people on Vancouver stations in the Golden Days of Radio to seek their fame on the other side of the border, including Arch Presby, Doug Gourlay, Fletcher Markle and the best-known of all, Alan Young. So I decided to dig a little further.

First, the story has the call letters wrong. A blurb in Weekly Variety of January 15, 1935 tells us: “Syd Chatton is a sports announcer for CKWX.”

Vancouver City Directories reveal Chatton was an usher at the Windsor Theatre (1931), a student employed at the Fraser Theatre (1932-33) and then an inspector for Empire Films Ltd. (1934-36).

“Joined the Don Lee network” means Chatton landed a job at KPO San Francisco. His impressions were good enough that Kay Jewelry of Oakland dumped its Kay Matinee show (handled by the University of California players) and sponsored him in a 15-minute programme called “Stars on Parade.” Billboard reviewed it on January 30, 1937. American network radio apparently called for higher standards of programming than what he was used to in local radio.

“Stars on Parade”By April, Chatton has moved to Los Angeles where he appeared at the Paramount Theatre, was tested for films and picked up whatever radio work he could. Then he got a big break. By 1938, he was picked to fill a vacancy on a trio called the Radio Rogues, who had begun to appear on independent stations in the New York City area in late 1931. Here’s a story in the Brooklyn Eagle from December 5, 1939 where they wave the local flag, even though Chatton was from Vancouver.

Reviewed Sunday, January 17, 4:15-4:30 p.m. Style—Talk. Sponsor—Kay Jewelry Company. Station—KPO and Coast NBC Red Network.

Except for the announcer (Grant Pollock) and the pianist who plays the theme, You Ought To Be in Pictures, this is a one-man show, but the man has many voices. He is Syd Chatton, 23-year-old imitator, late of the Canadian Broadcasting Company.

Idea of the show is the presentation of scenes from the current United Artist pictures, which Chatton doing a takeoff on the stars. This program was devoted to scenes from Charles Laughton’s Rembrandt, and all voices except female were Chatton’s. A novel note at the beginning was his simulation of the Coast’s well-known newscaster, Sam Hayes, to give the picture a plug. The announcer then gave a commercial and set the scene. Chatton did three scenes from the film, all with long Laughton speeches. Altho the lad’s imitation of the Laughton voice and vocal mannerisms were excellent, there was just too much. With no other known male star in the flicker, this could not be helped. A few lines of grade-A imitation is swell, but a quarter-hour makes the listener uncomfortable. More characters for Chatton to do would lend contrast and display a versatility which he had no chance to show on today’s offering.

Pollock read acceptable commercials in acceptable fashion, ending with the sponsor’s clever trade-mark, “It’s okeh to owe Kay.” P.K.

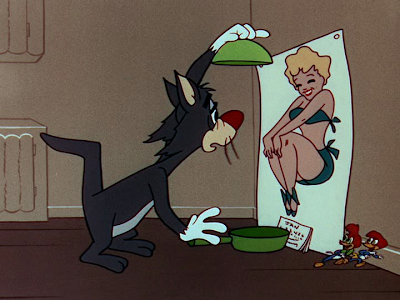

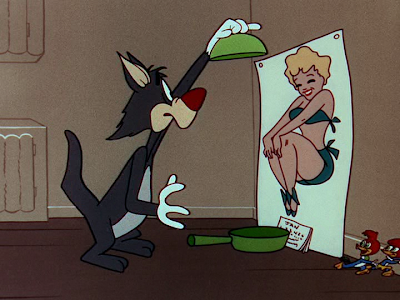

BROOKLYN BOYS MAKE GOODThe Radio Rogues also supplied voices for cartoons, but voice historian Keith Scott points out this was around 1934-35 before Chatton was with them.

By JANE CORBY

When somebody mentions the Radio Rogues, do you get a composite picture of Kate Smith, Adolf Hitler and Edward G. Robinson?

Me too.

The Radio Rogues, the great impersonators, are so darn well known as everybody else that I set out to track them down as just themselves—Eddie Bartell, Jimmy Hollywood and Sidney Chatton. big applause-getters of the much-applauded show “Hellzapoppin.” The best place to track down an actor—or three actors is in their dressing room just before a show. They’re bound to be there. They may elude you after the show, but not before. They may not want to be interviewed, but you sit in their dressing room where they've got to change within a few minutes and they will—if you're a feminine interviewer—talk. But fast. The show must go on and so must their costumes.

“Oops! Sorry.”

That was me, modestly backing out into the hall again after a glimpse of somebody in a costume that might have been a gym outfit and wasn’t. This sort of thing is bound to happen backstage at the Winter Garden, where the dressing room doors are always left open. Having backed into the hall and a passing actor, already in costume, including a brilliant tan like nothing that ever came out of Florida (oops! sorry, again), I was immediately recalled. One of the Rogues—it turned out to be Eddie Bartell—was now safe within a dressing gown; another, Jimmy Hollywood, was implacably in street attire; the third, Sid Chatton, was all ready for the first scene.

“Look,” I said, “which is which?”

“I sing,” said Eddie Bartell.

“I do the comedy,” said Jimmy Hollywood.

“I do dramatic stuff,” said Sid Chatton.

“Begin at the beginning,” I said. “You came from Brooklyn—where?”

“Flatbush,” said Eddie Bartell. “I went to Erasmus Hall.”

“I came from around DeKalb Ave.,” said Jimmy Hollywood. I went to school up the State Holy Cross.”

“I didn't come from Brooklyn,” said Sid Chatton, “I started in Canada.”

But he fixed that; he's a citizen now.

Why “Rogues”?

“When we started out on the radio we did impersonations, just as we do now,” said Jimmy. “We figured that what we were doing was stealing other people’s stuff, so we figured ‘Radio Rogues’ just about fitted us.” “We did impersonations on WLTH and other Brooklyn stations years ago,” said Eddie Bartell. “We did hill-billies and the Happiness Boys and Phil Cook and all the popular radio personalities.”

“We were,” said Jimmy Hollywood, “terrific.”

“We had an occasional spot on the air,” said Eddie Bartell. “One night we had to fill in for an act that could not appear. We decided to do imitations and the announced joined us. It happened that a booking agent heard us and overnight we turned professional, became the Radio Rogues.

“We’ve made a lot of picture, too,” said Jimmy Hollywood.

They’ve gone over big in pictures, continue to go over big on the radio and have been going over big in “Hellzapoppin,” a show which is in its second year and doing great. Have they any further ambitions?

“We want to buy a $1,500 fur coat,” said Sid Chatton, “we can take turned wearing it.”

The Rogues are all big Rogues—they’ll need a large coat. Eddie Bartell is the real athlete of the lot. He was the theatrical soft-ball star last year.

“The Hellzapoppin team played every show in town, in Central Park, wherever we could get a court. We played six shows and were undefeated.”

This year the soft-ball team is being reorganized and a hockey team too.

“This show’s a job for the next six months,” said Jimmy Hollywood. “Everybody figures, with their job safe, they might as well have some fun on their days off.”

The Radio Rogues were with “Hellzapoppin” before it became a Broadway show. It started as a half-hour vaudeville show, playing around the country six months before its hilarity brought it to Broadway.

But they were well used to success before the show came along. They had a “terrific time” in London in 1935, when they gave a request performance before King George V and the then Prince of Wales and Prince of York. Afterward they were entertained at Buckingham Palace.

Eddie Bartell’s career started far removed from the radio and theater. He was a salesman for a sporting goods house. Jimmy Hollywood was a Wall Street clerk and Sidney Chatton actually started in the theater, working with a brother of Johnson, of the "Hellzapoppin' " Olsen and Johnson, who present the show as well as act in it.

The pictures the Rogues have made including “Thanks a Million,” “Every Night at Eight” and “Going Hollywood.” They all like pictures. Sid wants to be a producer. He’s a walking encyclopedia of information on who played in what picture when.

All three Rogues live in California, Sidney Chatton in Hollywood, Jimmy Hollywood and Eddie Bartell in the San Fernando Valley, where many of the famous stars have homes, including Andy Devine and Louise Fazenda. Jimmy Hollywood has six children—three boys and three girls—and two of the youngsters, a boy and a girl, are already in pictures.

The Rogues ran (individually) for the board of directors of AGVA, the vaudeville performers association, in New York in 1940. One publicity story claimed Chatton and Bartell bought a chunk of land in the Yukon with the idea of mining for gold on it. But Chatton ended up leaving the Rogues by 1944 and performing on his own around the U.S. through the end of the decade.

Our friend Mr. Scott says Chatton did a pretty good Gable impression in Reveille With Beverly. His abilities on stage generally received good reviews in the trade papers for voices you might expect: Jack Benny, Don Wilson, Fred Allen (his routine was based on stars attending a Benny party, kind of like the plot of the Warners cartoon Malibu Beach Party), Peter Lorre, Herbert Marshall, Paul Muni, Walter Winchell, Ned Sparks, Katharine Hepburn, even a send-up of the Bogie-Bergman dialogue from Casablanca.

And what does a Radio Rogue do when radio dies? Go into television, of course. But Chatton wasn’t performing. He was the director of film operations for WCBS-TV until he resigned in August 1953 to go back into radio; he became the morning disc jockey at KFRC San Francisco. Chatton headed south to KFWB in 1956 and immediately cast in the Warner Bros’ movie Top Secret Affair, then landed associate production work at KTLA for six months before returning to San Francisco and KCBS. He moved to KTVU-TV in 1959 and was almost a jack of all trades. He anchored news and sports, was in charge of film programming and at the time of his death was anchoring a movie show. Variety of April 10, 1963 marvelled:

Syd Chatton of KTVU ( Channel 2) had a busy weekend in mid-March: From his “Pepito” show on Channel 2 he was seen in a KRON-TV 6 o'clock movie, then as a cop on a KP1X rerun of “San Francisco Beat,” then appeared live on KTVU again as staff announcer for a basketball telecast.Chatton died of a coronary on October 6, 1966 at Alta Bates Hospital in Berkeley. His Variety obit, California state records and even his gravestone claim he was 48 at the time of death. He wasn’t. And if you’re wondering why his name was variously spelled “Syd” and “Sid,” there’s a reason for that. It wasn’t his name.

Show folk were known for shaving a few years off their ages; it’s a little more difficult today when elaborate government records are kept. Years ago, especially before World War Two, things were a little more laissez-faire. And Syd Chatton took the opportunity some time after leaving Canada for good that he’d erase five years from his age. The 1937 Billboard review has his correct age.

Albert Edward Chatton was born in Bolton, Lancashire, England on May 6, 1913. Canadian Passenger Lists available on the internet show young Mr. Chatton, age five weeks, and his mother Beatrice arrived in Quebec City by boat from England on his way to Vancouver on June 12, 1913. U.S. District Court Naturalizations records list both “Albert Edward” and “Syd” Chatton on the same declaration card dated January 25, 1937. Vancouver City Directories list him as both “Sid” and “Syd” so we can only presume it was a childhood nickname.

The one thing we haven’t mentioned about Chatton—he was in the cast of The Wonderful World of Wilbur Pope. It was a pilot for a TV series that never sold. Producer George Burns reworked it and recast it—Chatton was in San Francisco by that time—and it emerged as Mr. Ed, starring someone who was in Vancouver radio about the same time as Chatton, a chap named Alan Young.

P.S.: This post was more of an experiment than a semi-biography. When I started researching things decades ago, it meant parking yourself in a public library and transcribing what you found in microfilmed newspapers, magazines and census reports via pen-to-paper. The internet has changed all that. Granted, some newspaper (trade and otherwise) sites on-line are commercial, but if you can access them, there’s a wealth of information you can put together sitting at home on a computer. Such as this post.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)