Walter Lantz should have been a happy man in 1952. He announced in August he was doubling his staff and boosting his output from six to 13 cartoons for the coming season. His characters were making appearances in comic books. He had a division that made TV commercials (in March, Variety reported he had hired Homer Brightman, Phil Eastman and Bill Scott; the latter two likely didn’t stay long). A deal for a Woody Woodpecker book series had been signed with Simon and Schuster in March. The next year, he’d add Mike Maltese and Tex Avery to his staff and Bill Garity would develop a 3-D process for him (which was used in one cartoon, the Don Patterson-directed “Hypnotic Hick.”

Lantz happened to be in New York in December 1952, closing a deal with Coca-Cola for a series of commercials to run in theatres. Lantz was pretty publicity conscious and he sat down for a softball interview with a syndicated columnist named Alice Hughes. Not everything in her story is quite correct, but at least it doesn’t mention to bogus “honeymoon” story about Woody Woodpecker’s creation. Lantz comes across as an unassuming guy who likes cartoons, which is the impression he left a few years later as the somewhat stiff co-host of the Woody Woodpecker cartoon series for Kellogg’s.

WOODY WOODPECKER TAPS FOR RED CROSS BLOOD DONORS

New York, Dec. 29—Don’t know what the town of New Rochelle, a few miles off New York city limits, has that nourishes top cartoonists. But I do know that two of the best movie cartoon animators were born and brought up there. One is Paul Terry, widely known for Terry Tunes on film and for a huge circulation of comic books whose characters are always birds and animals, never people. Then there is Walter Lantz with whom I spent an hour while he was in New York en route for a vacation in Mexico. Lantz was apprenticed in 1916 as cartoonist under the late Gregory La Cava, animating others’ characters such as Katzenjammer Kids, Happy Hooligan and Krazy Kat. Soon, however, he created his own Pete the Pup, Dinky Doodle and others. Finally Oswald the Rabbit landed him a fancy contract with Universal Films in 1928.

Seven years later Lantz fell in love with a panda at a Chicago zoo, and thus Andy the Panda was born and is to this day his second most-profitmaking cartoon character. First is Woody Woodpecker, a real-life carpenter bird who annoyed artist Lantz by tapping a $200 hole in the roof of a California house Lantz and his former-actress wife, Grace Stafford, occupied.

The tap-tap peck and the cartoon character it inspired have since parlayed that $200 into $2,000,000 plus much fame and acclaim. Woody the Woodpecker became a song on the Hit Parade. Boys and girls formed clubs called by its name. It became a symbol for saving forestry and today Walter Lantz is enjoying the proudest moment of his life. Woody has gone into a minute-and-a-half film cartoon urging birds of all kinds to donate blood for Red Cross war-time blood-banks. Lantz gifted the Red Cross with this finished film.

The red-tipped woodpecker urges all his feathered friends to give blood. When it comes hit turn, the cartoon shows his crimson crew-cut dim into pale pink as his blood drains into the bloodbank. There are many laughs, yet also a strong encouragement to people to go and do likewise. You’ll be seeing this animated short in all movie theaters and on TV, and shortly afterward Walter Lantz will do another cartoon with his bird and beast characters exhorting the public to give blood for the purpose of obtaining the gamma globulin injection, an accepted preventive for polio.

“Are comic books harmful for children?” I asked. “Not the way we draw them,” said Lantz. “The Association of Animated Cartoon Producers, of which I am president, never has trouble with censorship. As we know our efforts are seen and heard by millions of children all over the world, we observe the strictest rules of taste and decency. We’re not even permitted to draw udders on cows, and Walt Disney, Paul Terry and I—four of the seven members of the Animated Cartoon Producers —often laugh at how school-teacherish we are at our work. But we realize that this profession has at traction for many young artists, and highest standards are necessary.

“It takes a good 10 years of experience before an artist can become a good cartoon animator. Besides a good background in art knowledge and drawing, he has to have a sense of timing like an actor, sensitivity of facial expression like a sculptor and the patience of a saint to make the 7000 drawings necessary for a 6-minute film. Each slightest movement of a bird or animal requires a separate drawing and the animators need two assistants to carry on their work. I employ 60 artists to make 19 films a year, including seven Woody Woodpecker pictures and others such as Andy Panda, Buzz Buzzard, Wally Walrus, also comic books and quite a few commercial films for big industrial firms. We work in our own Walter Lantz Bldg., in 17,000 square feet of space, where we do a full-scale production of animated cartoons and TV films.”

Walter Lantz is 50-ish, gray-haired, blue-eyed, not tall, very friendly homespun in manner and with a refreshing modesty for a movie producer. He earns ten times as much as his brother Michael Lantz, a sculptor, who is conceded by Walter to be ten times better than Walt himself as an artist. Exciting outlook for 1953 is his new series of Foolish Fables, which are animated movie cartoons burlesqued from well-known fairy tales, in modern dress and modern situations. Lantz-film cartoons are dubbed into seven different foreign languages for children all over the world to enjoy.

Saturday, 11 April 2015

Friday, 10 April 2015

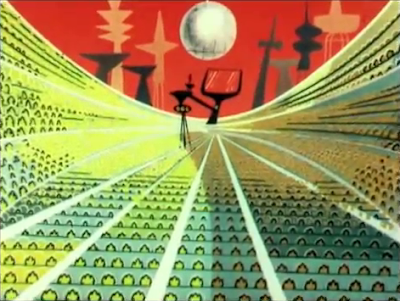

The Planet Moo

UPA cartoons became pretty much all about design, so let’s look at some designs from “Gerald McBoing! Boing! On Planet Moo.” First some backgrounds.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

And character designs.

.png)

.png)

.png)

I still don’t understand why it’s called the planet Moo. The characters there don’t say “moo.” Shouldn’t they? (The King is voiced by Marvin Miller like something out of Amos ‘n’ Andy).

Lew Keller was the designer.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

And character designs.

.png)

.png)

.png)

I still don’t understand why it’s called the planet Moo. The characters there don’t say “moo.” Shouldn’t they? (The King is voiced by Marvin Miller like something out of Amos ‘n’ Andy).

Lew Keller was the designer.

Labels:

UPA

Thursday, 9 April 2015

The Journey of a Cocoanut

The Half-Pint Pygmy (from the 1948 cartoon of the same name) tries to bop his hunters with a cocoanut he’s hoisted into a very tall tree. And it works.

.png)

But that sets off a string of gags as the cocoanut continues on its merry way after conking George and Junior on the head.

.png)

It klumps into a zebra, making the animal’s stripes drop off.

.png)

An ostrich shrinks.

.png)

.png)

In one kangaroo’s pouch and out the others. The kangaroos have Avery-type mouse ears.

.png)

The spots fall off a leopard.

.png)

A turtle is knocked out of its shell.

.png)

The neck on a giraffe contracts while a nearby hippo’s simultaneously grows.

.png)

A long-neck crane shrinks to the ground.

.png)

My favourite gag. The cocoanut goes over a goal post like a football, to the cheers of a crowd. Tex Avery and Heck Allen have a string of animal gags, so the football one comes out of nowhere.

.png)

The plates on a rhino fall off, revealing an emaciated creature (that pays no attention to what’s just happened).

.png)

The cocoanut bounces off each hump of a camel, sending them from the top of the animal’s body to the underside.

.png)

Finally, the cocoanut returns whence it came and crashes down on the pygmy.

Louie Schmitt, Walt Clinton, Grant Simmons and Bill Shull are the credited animators.

.png)

But that sets off a string of gags as the cocoanut continues on its merry way after conking George and Junior on the head.

.png)

It klumps into a zebra, making the animal’s stripes drop off.

.png)

An ostrich shrinks.

.png)

.png)

In one kangaroo’s pouch and out the others. The kangaroos have Avery-type mouse ears.

.png)

The spots fall off a leopard.

.png)

A turtle is knocked out of its shell.

.png)

The neck on a giraffe contracts while a nearby hippo’s simultaneously grows.

.png)

A long-neck crane shrinks to the ground.

.png)

My favourite gag. The cocoanut goes over a goal post like a football, to the cheers of a crowd. Tex Avery and Heck Allen have a string of animal gags, so the football one comes out of nowhere.

.png)

The plates on a rhino fall off, revealing an emaciated creature (that pays no attention to what’s just happened).

.png)

The cocoanut bounces off each hump of a camel, sending them from the top of the animal’s body to the underside.

.png)

Finally, the cocoanut returns whence it came and crashes down on the pygmy.

Louie Schmitt, Walt Clinton, Grant Simmons and Bill Shull are the credited animators.

Wednesday, 8 April 2015

Before the Band With a Thug

“Broadway Open House”? Before my time. “The Doodles Weaver Show”? Same thing. “Breakfast With Burrows” on radio? Definitely before my time. “The Gong Show”? Ah, that’s different. And that’s where I first heard the name Milton DeLugg.

His small orchestra was perhaps the only sane part of the show, a competent and enjoyable aggregation that was only involved musically. There was no hint that DeLugg had ever spoken on camera, let alone he had been a pioneer in the early days of network television.

DeLugg died this week at the age of 94.

The absolute best insight you can get into DeLugg’s career (and personality) is by heading to Kliph Nesteroff’s blog. Part One of his conversation is HERE. Part Two is HERE. It’s a terrific tete-a-tete.

How far did DeLugg go back? Well, the 1940 Census reports his occupation as “Musician, Radio Broadcasting.” He was with Matty Melnick’s band that year, and an Associated Press story that June says DeLugg’s “unruly mop of hair causes him to be known professionally as ‘O’Cedar.’”

Perhaps DeLugg’s everlasting accomplishment was he was the first sidekick bandleader when he was tabbed to provide the music for “Broadway Open House,” NBC’s first stab at late-night programming. Here’s a column that appeared in papers starting July 23, 1951. I believe it’s from the National Enterprise Association.

DE LUGG, NO RIVAL OF DAGMAR, STARS ON OWN ABILITY

By MARK BARRON

NEW YORK — Milton DeLugg, the droll accordion maestro of the "Broadway Open House" video program, may not be as pulchritudinously endowed as Dagmar, another alumnus of Jerry Lester's pre-midnite madness, but his wry wit, black cigar and adept musicianship have made him quite a character and attraction in his own right.

Milt’s father unknowingly started DeLugg on his musical way at the age of seven when he brought the boy home a miniature accordion. Within five years the youngster was being heralded as a boy wonder among musicians and he soon formed his own band in his Los Angeles High school.

Right now, DeLugg is at the stage of his career where he is five things at once. Although his naivete before the cameras draws laughs. Milt is foremost a musician and composer. His “Hoop-Dee-Doo” and “Orange Colored Sky” were number one songs on the Hit Parade for many weeks.

“Frankly, I didn't start out to be a comedian," he said. “At first, I didn't know whether the audiences were laughing with me or at me as I looked the part of a dupe which I had to play in many of the skits on the Lester show.”

Milt's private life seems to run true to the pattern set by his video personality. He met his wife when he was told to report to his draft board and she was behind the desk. His frau snared him first before he enlisted in the Air Force.

“Talk about the man behind the man behind the gun,” he said. “Well, my wife is the man behind the man behind the pun. Invariably people will ask me where I dream up some of my song titles as ‘Orange Colored Sky’ and ‘Hoop-dee-doo’, which seem to be a little off the beaten track.

“If I had had my way the titles would have been different and the royalties probably non-existent. My wife, the supposedly steady member of the family, was the one who stumped for the whacky titles and deserves a pat on the bankbook for their long runs on Hit Parade.”

And it was his young son who badgered him into taking him for a ride on the roller coaster at Steeplechase Park. Out of that ride came his “Roller Coaster,” an impressionistic piece which the symphonies across the country are greeting very favorably.

Steady work in TV followed DeLugg after the demise of “Broadway Open House.” In fact, he spent time with the programme’s successor, “The Tonight Show.” But he was gone in less than a year. Oddly, a United Press International column of July 21, 1967 opined: “Skitch Henderson, is not at ease as a foil for Johnny Carson; he simply is not funny.”

Here’s a piece published in the Binghamton Press, April 8, 1961. It must be an NBC news release; under no other circumstances would a newspaper use the phrase “on another network.” Looking at the names, you realise that DeLugg was a connection to an earlier era of show business.

● ● ●

Musician-composer Milton DeLugg became a well-known television personality as a regular on NBC-TV's first late-evening variety show Broadway Open House, then-spent a year trying to live down his fame.

"The program changed my career completely and created some serious problems for me," explains DeLugg, who is now music director for NBC-TV's The Jan Murray Show daytime color series.

"Before I went on Broadway Open House," DeLugg said, "no one heard of me. Although I had been in movies, on radio and TV, I was always in the background as a musician. But on this new informal show, everyone was involved in the hap-hazard on-camera proceedings.

"Blonde Dagmar, dancer Ray Malone, the Mellowlarks vocal group and myself all shared the spotlight with host Jerry Lester. And the boys in the band kidded around so much the group was nicknamed ‘DeLugg's Phony Philharmonic.’"

It was when the show left the air and DeLugg sought other assignments that his fame began to hinder him. He explains, "No one would believe I was a serious musician. As a result of the show, I had become a character. Everyone had the impression I was just a comical cigar-smoking accordion player. It took me a year to live down this image and once again become accepted as a capable musician. It was an experience I'll never forget."

It was inevitable that DeLugg as a serious musician would not be long hidden. Music has been a part of his life since he was seven, when his father brought home, a pint-sized accordion. Within five years DeLugg was an expert.

In high school he formed his own band and appeared, as an amateur accordionist, on Fred Allen's radio show. (Years later, without accordion, he was music director of Allen's TV series.)

After graduation he joined the Sons of the Pioneers and was staff musician at radio stations in his native Los Anueles, playing on the Rudy Vallee show and other programs.

He has appeared in movies with Al Jolson, Bing Crosby and Jack Benny; in Broadway musicals and at some of the country's top night spots. Since Broadway Open House DeLugg has been music director of almost a dozen television shows, Including NBC's All Star Revue, Fred Allen's show and Jan Murray's Treasure Hunt. He is currently also music director of The Paul Winchell Show on another network.

● ● ●

The Archive of American Television interviewed DeLugg a number of years ago. You can see it by going HERE.

His small orchestra was perhaps the only sane part of the show, a competent and enjoyable aggregation that was only involved musically. There was no hint that DeLugg had ever spoken on camera, let alone he had been a pioneer in the early days of network television.

DeLugg died this week at the age of 94.

The absolute best insight you can get into DeLugg’s career (and personality) is by heading to Kliph Nesteroff’s blog. Part One of his conversation is HERE. Part Two is HERE. It’s a terrific tete-a-tete.

How far did DeLugg go back? Well, the 1940 Census reports his occupation as “Musician, Radio Broadcasting.” He was with Matty Melnick’s band that year, and an Associated Press story that June says DeLugg’s “unruly mop of hair causes him to be known professionally as ‘O’Cedar.’”

Perhaps DeLugg’s everlasting accomplishment was he was the first sidekick bandleader when he was tabbed to provide the music for “Broadway Open House,” NBC’s first stab at late-night programming. Here’s a column that appeared in papers starting July 23, 1951. I believe it’s from the National Enterprise Association.

DE LUGG, NO RIVAL OF DAGMAR, STARS ON OWN ABILITY

By MARK BARRON

NEW YORK — Milton DeLugg, the droll accordion maestro of the "Broadway Open House" video program, may not be as pulchritudinously endowed as Dagmar, another alumnus of Jerry Lester's pre-midnite madness, but his wry wit, black cigar and adept musicianship have made him quite a character and attraction in his own right.

Milt’s father unknowingly started DeLugg on his musical way at the age of seven when he brought the boy home a miniature accordion. Within five years the youngster was being heralded as a boy wonder among musicians and he soon formed his own band in his Los Angeles High school.

Right now, DeLugg is at the stage of his career where he is five things at once. Although his naivete before the cameras draws laughs. Milt is foremost a musician and composer. His “Hoop-Dee-Doo” and “Orange Colored Sky” were number one songs on the Hit Parade for many weeks.

“Frankly, I didn't start out to be a comedian," he said. “At first, I didn't know whether the audiences were laughing with me or at me as I looked the part of a dupe which I had to play in many of the skits on the Lester show.”

Milt's private life seems to run true to the pattern set by his video personality. He met his wife when he was told to report to his draft board and she was behind the desk. His frau snared him first before he enlisted in the Air Force.

“Talk about the man behind the man behind the gun,” he said. “Well, my wife is the man behind the man behind the pun. Invariably people will ask me where I dream up some of my song titles as ‘Orange Colored Sky’ and ‘Hoop-dee-doo’, which seem to be a little off the beaten track.

“If I had had my way the titles would have been different and the royalties probably non-existent. My wife, the supposedly steady member of the family, was the one who stumped for the whacky titles and deserves a pat on the bankbook for their long runs on Hit Parade.”

And it was his young son who badgered him into taking him for a ride on the roller coaster at Steeplechase Park. Out of that ride came his “Roller Coaster,” an impressionistic piece which the symphonies across the country are greeting very favorably.

Steady work in TV followed DeLugg after the demise of “Broadway Open House.” In fact, he spent time with the programme’s successor, “The Tonight Show.” But he was gone in less than a year. Oddly, a United Press International column of July 21, 1967 opined: “Skitch Henderson, is not at ease as a foil for Johnny Carson; he simply is not funny.”

Here’s a piece published in the Binghamton Press, April 8, 1961. It must be an NBC news release; under no other circumstances would a newspaper use the phrase “on another network.” Looking at the names, you realise that DeLugg was a connection to an earlier era of show business.

● ● ●

Musician-composer Milton DeLugg became a well-known television personality as a regular on NBC-TV's first late-evening variety show Broadway Open House, then-spent a year trying to live down his fame.

"The program changed my career completely and created some serious problems for me," explains DeLugg, who is now music director for NBC-TV's The Jan Murray Show daytime color series.

"Before I went on Broadway Open House," DeLugg said, "no one heard of me. Although I had been in movies, on radio and TV, I was always in the background as a musician. But on this new informal show, everyone was involved in the hap-hazard on-camera proceedings.

"Blonde Dagmar, dancer Ray Malone, the Mellowlarks vocal group and myself all shared the spotlight with host Jerry Lester. And the boys in the band kidded around so much the group was nicknamed ‘DeLugg's Phony Philharmonic.’"

It was when the show left the air and DeLugg sought other assignments that his fame began to hinder him. He explains, "No one would believe I was a serious musician. As a result of the show, I had become a character. Everyone had the impression I was just a comical cigar-smoking accordion player. It took me a year to live down this image and once again become accepted as a capable musician. It was an experience I'll never forget."

It was inevitable that DeLugg as a serious musician would not be long hidden. Music has been a part of his life since he was seven, when his father brought home, a pint-sized accordion. Within five years DeLugg was an expert.

In high school he formed his own band and appeared, as an amateur accordionist, on Fred Allen's radio show. (Years later, without accordion, he was music director of Allen's TV series.)

After graduation he joined the Sons of the Pioneers and was staff musician at radio stations in his native Los Anueles, playing on the Rudy Vallee show and other programs.

He has appeared in movies with Al Jolson, Bing Crosby and Jack Benny; in Broadway musicals and at some of the country's top night spots. Since Broadway Open House DeLugg has been music director of almost a dozen television shows, Including NBC's All Star Revue, Fred Allen's show and Jan Murray's Treasure Hunt. He is currently also music director of The Paul Winchell Show on another network.

● ● ●

The Archive of American Television interviewed DeLugg a number of years ago. You can see it by going HERE.

Stan Freberg and the 61st Second

A lot of words have been thrown around about Stan Freberg upon his death yesterday. Let me toss in a couple of my own—insightful and articulate. One has to have both traits in volume to be a good satirist. And, that, Freberg was.

Freberg was no fan of rock-and-roll, political correctness, or the inanities of electronic media programming and advertising. He took no prisoners in “Elderly Man River,” a truly marvellous sketch where he butchered the lyrics of a Stephen Foster classic beyond recognition so it couldn’t possibly offend anyone. He saw through the showmanship of Elvis Presley and Johnny Ray by slashing and slicing their hits “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Cry,” technically and lyrically. His Jeno’s Pizza Rolls TV commercial seems to have been sparked by his umbrage that someone other than The Lone Ranger could dare to co-opt The William Tell Overture. “Green Christmas” took aim at commercialism of a religious holiday (Freberg’s father was a minister) before Charles Schulz did the same thing with some kids in a Christmas TV special. Some of his satire is awe-inspiring. You listen to it and can’t help but admire the cleverness and appreciate his intellect.

Parody was in his arsenal, too. His Jack Webb-inspired “St. George and the Dragonet” could be said to have sparked an entire comedy record industry.

And that was only the tip of the... well, I’d say “Fre-berg” but he’s used that one already. He began his entertainment career as a voice actor in cartoons. Warner Bros. fans (he worked for Columbia and UPA as well) can probably pick out a favourite. They’re liable to disagree on his best work; Freberg worked on great cartoons for a couple of directors. He moved on to the puppet show “Time For Beany,” eventually walking away with collaborator Daws Butler. Evidently Freberg didn’t think a lot of Beany’s creator, Bob Clampett; he went on TV with a Cecil-like creature and Clampett promptly sued. Children’s and comedy records followed, then his huge career in advertising. Sponsor magazine profiled him and his ad philosophies in its edition of October 14, 1963. You can read it (in pdf form) HERE.

I don’t have any personal stories about him; he spoke at a seminar locally years ago that was beyond my price range to attend. So allow me to purloin part of a feature story by Bert Prelutsky of the Los Angeles Times from June 25, 1967. Ken Sullet quoted in the story worked with him on the comedy album Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America. The other voice actor mentioned not only did an incredible amount of commercials using a variety of voices, he was the best part of “The Alvin Show” as inventor Clyde Crashcup.

● ● ●

During the first week of February he [Freberg] was to record eight radio commercials for a Chrysler campaign. The dual points of the campaign were that Plymouth had a tremendous selection of new models and colors, and that Plymouth dealers would go to any lengths to make you a deal on the one car just right for you. The eight spots were about one such dealer’s going mad trying to sell a Plymouth to a customer who couldn’t even decide what he wanted for breakfast.

One such recording session began at 5 in the afternoon at Radio Recorders Stage B, on Melrose, one of the only two studios in town with acoustics good enough for Freberg. (The other is at Capitol). By 1 o’clock in the morning, Shep Menkin, one of the best men in the business, who’s play the Plymouth dealer in the campaign, still hasn’t said line one into the mike. The reason: Freberg has been on Orange Drive all evening with a block-long extension cord, recording a passing cavalcade of Plymouth Furies. Up and down the street he’s had them for hours. At one point, though, a metallic gray Jag drove by with a For Sale sign in the window. Freberg jumped into one of the passing Furies. “Follow that Jag!” he tells the driver. Twenty minutes later he returns. It turns out he’d driven a metallic gray Jag on his honeymoon and he’s decided to buy this one.

In 1959 he married his secretary, Donna Andresen. Today she’s irreplaceable, not merely as a wife, but as one of the few people in the business he feels he can count on. She works in the studio, helping to edit the spots, sees to it that he meets deadlines, acts as a buffer between her husband and a sometimes belligerent world of clients, and serves as Freberg’s first reactor to new material.

A bright, attractive blonde in her 30s, she answers the question why Freberg works himself so hard: “He feels he has to do it the right way every time. I guess he thinks someone won’t get it. He even gets worked up reading his stuff to me. I tell him, you don’t have to sell it to me. But you can’t change him.” But she tries, anyway.

Freberg admits, “My wife is waging a campaign—less procrastination, less deliberation, less vacillation. I’m the guy in the Plymouth spots who can’t make up his mind.”

The Great Vacillator, in fact, is the nickname Sullet has given Freberg. “Never,” he advises, “go out for dinner with Freberg. You’re in a restaurant, sitting with him and four other people, and it begins.” Sullet suddenly gets a nasal twang in his voice, a pretty fair approximation of the Freberg delivery: “ ‘What are you having? The prime rib?. . .You think I’d like it?. . .You’d recommend it?. . .You really think I ought to have the prime rib?’’ He goes around the entire table that way. Finally the waiter comes and Freberg asks him what he should order. ‘The lobster, huh?. . . You’d recommend it highly?. . .I’ll be happy with it?’ So he orders the lobster. Suddenly he’s stretching his neck and staring over our heads at a table halfway across the room. ‘What’s that woman having over there? A London broil?. . .It looks kind of good. . .Waiter! Waiter!’”

Back at Radio Recorders, it’s 1:15 a.m. Freberg has gotten the Furies recorded and has made an offer on the Jag. He and Menkin are sitting at a card table, discussing the spot. In the sound booth, Donna and a couple of engineers are chatting and growing old.

Menkin and Freberg are trying out different readings. Finally they’re ready for the mike. After a few false starts, they go through the entire spot. Because of a nine-second Plymouth tag, they have only 51 seconds to work with. They finish the spot. It sounds good. They look at the booth, where Donna is shaking her head. It’s 10 seconds long.

Freberg throws his pencil at the music stand. “Who says a commercial has to be 60 seconds? Who’s the FCC anyway?”

They make a few cuts in the copy and try another take. This one is longer than the first; they’ve delivered their lines slower.

At 2:15, Freberg takes a vitamin B12.

By 2:30, they’re on take 21. It’s a good one, but the time is still two seconds too long. Freberg wants “One more take, just one more. . .” They do another take. Still two seconds too long.

At 2:35, the Frebergs argue about the wisdom of trying to fix the spot at this time. She wants him to go home. He wants to record. He wins.

At 2:37 he’s down on the floor doing push-ups.

Menkin stands watching. “Sun flower seeds, wheat germ, vitamins; he swims in his pool every day. He’s a nut about that stuff.”

Freberg disagrees. “I’m not a health food nut. I just eat more healthily than most people.”

It’s 2:53. They have managed to cut one of the two troublesome seconds out. Freberg is in the booth now, with his stop watch. “It’s a 61-second spot no matter how you slice it. Well, I’ll just tell the Plymouth dealers there’s something wrong with their watches.” He’s kidding.

He and Menkin go back to the mikes and wage war against a second of time. By 3:05 they’re still losing.

“Tell me what to do,” Freberg says to Donna. “If you want me to stay and try again, I’ll do it.” Everybody laughs.

Finally at 3:45, somehow they’ve done it. A poor battered and bleeding second, its tail between its legs, has crawled off to recuperate. It will be back, though. A battle’s a battle; a war is something else. And in Freberg’s experience, the 61st second has never failed to come out swinging when the next bell rings.

In the next two days and nights, Freberg’s supposed to record seven more spots. He won’t. He’ll have six spots completed when he sends the campaign to Detroit on Thursday morning.

During his recording sessions, he will suck on Pine Brothers honey cough drops and special vocal lozenges. After eight or nine hours in the studio, he will break out his Lif-O-Gen oxygen unit and take a few deep breaths, and then keep going into “The Golden Hours,” his apt name for overtime.

In the end, Menkin will say “That Freberg can really fuss away time. He comes up with a sensational product—but he wastes too much time. It’s not necessary.” Of course, it is necessary. It’s necessary because that’s the only way Freberg can function.

● ● ●

Want more Freberg? Seek out his 1957 radio show on CBS on-line. We’ve got some old newspaper articles quoting him HERE and HERE. But the best way I can end this post is to direct you to Mark Evanier’s remembrance of him HERE. Mark’s pretty insightful and articulate, too.

Freberg was no fan of rock-and-roll, political correctness, or the inanities of electronic media programming and advertising. He took no prisoners in “Elderly Man River,” a truly marvellous sketch where he butchered the lyrics of a Stephen Foster classic beyond recognition so it couldn’t possibly offend anyone. He saw through the showmanship of Elvis Presley and Johnny Ray by slashing and slicing their hits “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Cry,” technically and lyrically. His Jeno’s Pizza Rolls TV commercial seems to have been sparked by his umbrage that someone other than The Lone Ranger could dare to co-opt The William Tell Overture. “Green Christmas” took aim at commercialism of a religious holiday (Freberg’s father was a minister) before Charles Schulz did the same thing with some kids in a Christmas TV special. Some of his satire is awe-inspiring. You listen to it and can’t help but admire the cleverness and appreciate his intellect.

Parody was in his arsenal, too. His Jack Webb-inspired “St. George and the Dragonet” could be said to have sparked an entire comedy record industry.

And that was only the tip of the... well, I’d say “Fre-berg” but he’s used that one already. He began his entertainment career as a voice actor in cartoons. Warner Bros. fans (he worked for Columbia and UPA as well) can probably pick out a favourite. They’re liable to disagree on his best work; Freberg worked on great cartoons for a couple of directors. He moved on to the puppet show “Time For Beany,” eventually walking away with collaborator Daws Butler. Evidently Freberg didn’t think a lot of Beany’s creator, Bob Clampett; he went on TV with a Cecil-like creature and Clampett promptly sued. Children’s and comedy records followed, then his huge career in advertising. Sponsor magazine profiled him and his ad philosophies in its edition of October 14, 1963. You can read it (in pdf form) HERE.

I don’t have any personal stories about him; he spoke at a seminar locally years ago that was beyond my price range to attend. So allow me to purloin part of a feature story by Bert Prelutsky of the Los Angeles Times from June 25, 1967. Ken Sullet quoted in the story worked with him on the comedy album Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America. The other voice actor mentioned not only did an incredible amount of commercials using a variety of voices, he was the best part of “The Alvin Show” as inventor Clyde Crashcup.

● ● ●

During the first week of February he [Freberg] was to record eight radio commercials for a Chrysler campaign. The dual points of the campaign were that Plymouth had a tremendous selection of new models and colors, and that Plymouth dealers would go to any lengths to make you a deal on the one car just right for you. The eight spots were about one such dealer’s going mad trying to sell a Plymouth to a customer who couldn’t even decide what he wanted for breakfast.

One such recording session began at 5 in the afternoon at Radio Recorders Stage B, on Melrose, one of the only two studios in town with acoustics good enough for Freberg. (The other is at Capitol). By 1 o’clock in the morning, Shep Menkin, one of the best men in the business, who’s play the Plymouth dealer in the campaign, still hasn’t said line one into the mike. The reason: Freberg has been on Orange Drive all evening with a block-long extension cord, recording a passing cavalcade of Plymouth Furies. Up and down the street he’s had them for hours. At one point, though, a metallic gray Jag drove by with a For Sale sign in the window. Freberg jumped into one of the passing Furies. “Follow that Jag!” he tells the driver. Twenty minutes later he returns. It turns out he’d driven a metallic gray Jag on his honeymoon and he’s decided to buy this one.

In 1959 he married his secretary, Donna Andresen. Today she’s irreplaceable, not merely as a wife, but as one of the few people in the business he feels he can count on. She works in the studio, helping to edit the spots, sees to it that he meets deadlines, acts as a buffer between her husband and a sometimes belligerent world of clients, and serves as Freberg’s first reactor to new material.

A bright, attractive blonde in her 30s, she answers the question why Freberg works himself so hard: “He feels he has to do it the right way every time. I guess he thinks someone won’t get it. He even gets worked up reading his stuff to me. I tell him, you don’t have to sell it to me. But you can’t change him.” But she tries, anyway.

Freberg admits, “My wife is waging a campaign—less procrastination, less deliberation, less vacillation. I’m the guy in the Plymouth spots who can’t make up his mind.”

The Great Vacillator, in fact, is the nickname Sullet has given Freberg. “Never,” he advises, “go out for dinner with Freberg. You’re in a restaurant, sitting with him and four other people, and it begins.” Sullet suddenly gets a nasal twang in his voice, a pretty fair approximation of the Freberg delivery: “ ‘What are you having? The prime rib?. . .You think I’d like it?. . .You’d recommend it?. . .You really think I ought to have the prime rib?’’ He goes around the entire table that way. Finally the waiter comes and Freberg asks him what he should order. ‘The lobster, huh?. . . You’d recommend it highly?. . .I’ll be happy with it?’ So he orders the lobster. Suddenly he’s stretching his neck and staring over our heads at a table halfway across the room. ‘What’s that woman having over there? A London broil?. . .It looks kind of good. . .Waiter! Waiter!’”

Back at Radio Recorders, it’s 1:15 a.m. Freberg has gotten the Furies recorded and has made an offer on the Jag. He and Menkin are sitting at a card table, discussing the spot. In the sound booth, Donna and a couple of engineers are chatting and growing old.

Menkin and Freberg are trying out different readings. Finally they’re ready for the mike. After a few false starts, they go through the entire spot. Because of a nine-second Plymouth tag, they have only 51 seconds to work with. They finish the spot. It sounds good. They look at the booth, where Donna is shaking her head. It’s 10 seconds long.

Freberg throws his pencil at the music stand. “Who says a commercial has to be 60 seconds? Who’s the FCC anyway?”

They make a few cuts in the copy and try another take. This one is longer than the first; they’ve delivered their lines slower.

At 2:15, Freberg takes a vitamin B12.

By 2:30, they’re on take 21. It’s a good one, but the time is still two seconds too long. Freberg wants “One more take, just one more. . .” They do another take. Still two seconds too long.

At 2:35, the Frebergs argue about the wisdom of trying to fix the spot at this time. She wants him to go home. He wants to record. He wins.

At 2:37 he’s down on the floor doing push-ups.

Menkin stands watching. “Sun flower seeds, wheat germ, vitamins; he swims in his pool every day. He’s a nut about that stuff.”

Freberg disagrees. “I’m not a health food nut. I just eat more healthily than most people.”

It’s 2:53. They have managed to cut one of the two troublesome seconds out. Freberg is in the booth now, with his stop watch. “It’s a 61-second spot no matter how you slice it. Well, I’ll just tell the Plymouth dealers there’s something wrong with their watches.” He’s kidding.

He and Menkin go back to the mikes and wage war against a second of time. By 3:05 they’re still losing.

“Tell me what to do,” Freberg says to Donna. “If you want me to stay and try again, I’ll do it.” Everybody laughs.

Finally at 3:45, somehow they’ve done it. A poor battered and bleeding second, its tail between its legs, has crawled off to recuperate. It will be back, though. A battle’s a battle; a war is something else. And in Freberg’s experience, the 61st second has never failed to come out swinging when the next bell rings.

In the next two days and nights, Freberg’s supposed to record seven more spots. He won’t. He’ll have six spots completed when he sends the campaign to Detroit on Thursday morning.

During his recording sessions, he will suck on Pine Brothers honey cough drops and special vocal lozenges. After eight or nine hours in the studio, he will break out his Lif-O-Gen oxygen unit and take a few deep breaths, and then keep going into “The Golden Hours,” his apt name for overtime.

In the end, Menkin will say “That Freberg can really fuss away time. He comes up with a sensational product—but he wastes too much time. It’s not necessary.” Of course, it is necessary. It’s necessary because that’s the only way Freberg can function.

● ● ●

Want more Freberg? Seek out his 1957 radio show on CBS on-line. We’ve got some old newspaper articles quoting him HERE and HERE. But the best way I can end this post is to direct you to Mark Evanier’s remembrance of him HERE. Mark’s pretty insightful and articulate, too.

Tuesday, 7 April 2015

Open Wide

Wide-open mouths aplenty in the only Art Davis-directed Bugs Bunny cartoon, “Bowery Bugs.” And finger gestures, too. They don’t move as wildly as in a Bob McKimson cartoon about this time, but the movement isn’t as restrained as in a Jones or Freleng Bugs.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Some drawings of Bugs have him with long, thin front teeth while others have him with shorter, chisel-shaped ones. Emery Hawkins, Basil Davidovich, Bill Melendez and Don Williams are the credited animators.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Some drawings of Bugs have him with long, thin front teeth while others have him with shorter, chisel-shaped ones. Emery Hawkins, Basil Davidovich, Bill Melendez and Don Williams are the credited animators.

Labels:

Art Davis,

Warner Bros.

Monday, 6 April 2015

Long Arm of the Teenager

Jeannie the babysitter can’t wait to gab on the phone in “Tot Watchers” (released August 1958). Her arm stretches in an Avery-like exaggeration and pulls her toward the phone. Look, folks! It’s a Cinemascope gag!

.png)

.png)

.png)

Tom gets a stretch job himself.

.png)

Below, Jeannie is in shock when she realises there’s no cord connecting the handset to the phone. Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera are already learning how to cut corners as they anticipate TV animation, although even the cheap Yogi Bear cartoons had a phone cord when needed.

.png)

This sorry cartoon brought to an end the Tom and Jerrys made on the Metro lot in Culver City. Ken Muse, Lew Marshall and Jim Escalante get the animation credits. The old Hanna-Barbera unit had pretty much broken up. Ed Barge (Billboard, May 5, 1956) and Irv Spence (Variety, Aug. 30, 1956) had left for commercial house Animation, Inc. Muse and Marshall would follow Hanna and Barbera to their own studio, Escalante was an effects animator who apparently went into the ministry.

Happy Homer Brightman received the screen credit for the story. The cartoon would have been started before July 18, 1956 as that’s when Variety announced Walter Lantz had signed Brightman to an exclusive, five-year contract (Brightman had been freelancing the previous two years).

The voice actors on this cartoon are a little baffling, other than Bill Thompson pulls out his Irish accent to the play the sceptical cop (a staple stereotype in later Hanna-Barbera TV cartoons). No, Janet Waldo is not the voice of Jeannie. If I recall, voice historian Keith Scott said the babysitter was played by Louise Erickson, who (like Waldo) made a career playing squealing teenaged girls on network radio. The mother may be Perry Sheehan; Variety reported on April 13, 1956 that she and Dick Anderson had been signed by MGM to supply voices for the suburbanite couple in the Tom and Jerry cartoon “The Vanishing Duck.”

.png)

.png)

.png)

Tom gets a stretch job himself.

.png)

Below, Jeannie is in shock when she realises there’s no cord connecting the handset to the phone. Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera are already learning how to cut corners as they anticipate TV animation, although even the cheap Yogi Bear cartoons had a phone cord when needed.

.png)

This sorry cartoon brought to an end the Tom and Jerrys made on the Metro lot in Culver City. Ken Muse, Lew Marshall and Jim Escalante get the animation credits. The old Hanna-Barbera unit had pretty much broken up. Ed Barge (Billboard, May 5, 1956) and Irv Spence (Variety, Aug. 30, 1956) had left for commercial house Animation, Inc. Muse and Marshall would follow Hanna and Barbera to their own studio, Escalante was an effects animator who apparently went into the ministry.

Happy Homer Brightman received the screen credit for the story. The cartoon would have been started before July 18, 1956 as that’s when Variety announced Walter Lantz had signed Brightman to an exclusive, five-year contract (Brightman had been freelancing the previous two years).

The voice actors on this cartoon are a little baffling, other than Bill Thompson pulls out his Irish accent to the play the sceptical cop (a staple stereotype in later Hanna-Barbera TV cartoons). No, Janet Waldo is not the voice of Jeannie. If I recall, voice historian Keith Scott said the babysitter was played by Louise Erickson, who (like Waldo) made a career playing squealing teenaged girls on network radio. The mother may be Perry Sheehan; Variety reported on April 13, 1956 that she and Dick Anderson had been signed by MGM to supply voices for the suburbanite couple in the Tom and Jerry cartoon “The Vanishing Duck.”

Labels:

Hanna and Barbera unit,

MGM

Sunday, 5 April 2015

I Just Happen To Have Some Gags...

How did Jack Benny find time to go on the air?

He always seems to have been all over North America, attending fund-raisers or banquets or some similar thing.

Here’s a 1950 newspaper story about Benny meeting up with a bunch of reporters. In New York City. On his birthday. He was in New York for a benefit for the Heart Fund and had broadcast a couple of his radio shows from the city. It claims he ad-libbed a speech at a lunch honouring him. It could be true. But I can’t help but thing he didn’t walk in unprepared.

Radio Ringside

Distributed by International News Service

By JOHN M. COOPER

New York, Feb. 16 —(INS)— Jack Benny claims he’s no good with the ad-libs and is lost without a script full of jokes.

He admits quite cheerfully all the charges that Fred Allen has made to that effect. He will even quote Allen’s remarks.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that Benny can make a very funny ad-lib speech, and in fact has done so many times during the last few weeks while he has been visiting New York.

Yesterday, just before taking the train back to Los Angeles, he outdid himself at a “Banshee" luncheon honoring Bill Hutchinson, Washington bureau chief for International News Service. The Banshees are a group of top newspapermen, and a lot of famous people were on hand to celebrate Hutchinson’s 30th anniversary with INS.

It was also Benny’s 56th birthday, and the Banshees took the opportunity to make him a life member of their organization. They gave him a handsome plaque to prove it. So Benny made a speech.

He said he had made a lot of speeches in behalf of such things as the Heart fund, the March of Dimes, etc., and it was nice, for a change, not to have to appeal for funds.

“Of course,” Jack added, “if any of you want to contribute something, it’s okay with me. It’s a long, expensive trip back to Los Angeles.”

Some photographers who were taking pictures moved him to remark that he hadn’t yet seen any pictures of himself in the New York papers.

“Except,” he added, “that I finally found one in the Daily Worker. But I still can’t understand how they got that hammer and sickle in my hand.”

Benny remarked that the government tax experts haven’t yet decided whether to approve his famous capital gains deal, under which he left NBC for CBS. He explained:

“I said it was a capital gains deal. They said the gain should go to the capital, which is in Washington.”

As for the plaque given him by the Banshees, he wondered whether he would have to give it to CBS Board Chairman William S. Paley.

“When he bought me,” said Benny, “he bought everything.”

Jack even tossed in a remark for the Waldorf Astoria hotel, where the luncheon was held. He said:

“It’s a nice hotel, but I can’t afford to stay in it. It’s the only hotel I know where you have to be shaved before they let you in the barber shop.”

He always seems to have been all over North America, attending fund-raisers or banquets or some similar thing.

Here’s a 1950 newspaper story about Benny meeting up with a bunch of reporters. In New York City. On his birthday. He was in New York for a benefit for the Heart Fund and had broadcast a couple of his radio shows from the city. It claims he ad-libbed a speech at a lunch honouring him. It could be true. But I can’t help but thing he didn’t walk in unprepared.

Radio Ringside

Distributed by International News Service

By JOHN M. COOPER

New York, Feb. 16 —(INS)— Jack Benny claims he’s no good with the ad-libs and is lost without a script full of jokes.

He admits quite cheerfully all the charges that Fred Allen has made to that effect. He will even quote Allen’s remarks.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that Benny can make a very funny ad-lib speech, and in fact has done so many times during the last few weeks while he has been visiting New York.

Yesterday, just before taking the train back to Los Angeles, he outdid himself at a “Banshee" luncheon honoring Bill Hutchinson, Washington bureau chief for International News Service. The Banshees are a group of top newspapermen, and a lot of famous people were on hand to celebrate Hutchinson’s 30th anniversary with INS.

It was also Benny’s 56th birthday, and the Banshees took the opportunity to make him a life member of their organization. They gave him a handsome plaque to prove it. So Benny made a speech.

He said he had made a lot of speeches in behalf of such things as the Heart fund, the March of Dimes, etc., and it was nice, for a change, not to have to appeal for funds.

“Of course,” Jack added, “if any of you want to contribute something, it’s okay with me. It’s a long, expensive trip back to Los Angeles.”

Some photographers who were taking pictures moved him to remark that he hadn’t yet seen any pictures of himself in the New York papers.

“Except,” he added, “that I finally found one in the Daily Worker. But I still can’t understand how they got that hammer and sickle in my hand.”

Benny remarked that the government tax experts haven’t yet decided whether to approve his famous capital gains deal, under which he left NBC for CBS. He explained:

“I said it was a capital gains deal. They said the gain should go to the capital, which is in Washington.”

As for the plaque given him by the Banshees, he wondered whether he would have to give it to CBS Board Chairman William S. Paley.

“When he bought me,” said Benny, “he bought everything.”

Jack even tossed in a remark for the Waldorf Astoria hotel, where the luncheon was held. He said:

“It’s a nice hotel, but I can’t afford to stay in it. It’s the only hotel I know where you have to be shaved before they let you in the barber shop.”

Labels:

Jack Benny

Saturday, 4 April 2015

Felix and the Flapper

Sure, Betty Boop somewhat epitomised the Roaring ‘20s (even they were dead by the time she debuted), but the cartoon character who hung out with flappers was Felix the Cat. Well, one flapper, anyway.

The January 1927 edition of Photoplay magazine included a two-page spread of Felix dancing the Black Bottom with the woman who popularised it, Ann Pennington. She danced in the Ziegfeld Follies and George White Scandals. But age has a habit of creeping up on dancers and Pennington finally retired during World War Two—and spent much of the rest of her life on welfare, living in rooming hotels on (appropriate for a dancer, I suppose), 42nd Street.

The Black Bottom was one of her dances; butt-slapping dances crop up occasionally in the cartoons of the New York studios in the early ‘30s. In Photoplay, she’s shown teaching it to Felix who, though he has a black bottom, never did the dance in any cartoons that I can recall off-hand. Here are the photos from Photoplay, with the text that accompanies each picture.

Felix decides that the Charleston is passé and goes to Ann Pennington for a lesson in the Black Bottom. In the first step, Ann points her left foot to the side, raising the left heel from the floor, bending both knees and slanting her body backwards

Second step. “Now, Felix,” says Ann, “straighten the body, lower the left heel and point your toe up from the floor. And, Felix, sing that song, ‘The Black Bottom of the Swanee River, sometimes likes to shake and shiver.’ A little more pep, please!”

“Come on, cat! All set for the third step. Face forward, Felix, and bend that left knee slightly, pointing the left paw toward the floor. This is the way we make ‘em sit up and take notice when we dance the ‘Black Bottom’ in Mr. White's ‘Scandals’.”

“Snap into the fourth step, funny feline! Stamp that left mouse-catcher on the floor and bend that left knee. Stamp it good and hard. And sing that song—‘They call it Black Bottom, a new twister. They sure got ‘em, oh sister!’”

“Now, Mr. Cream and Catnip Man, after stamping forward, drag the left paw back across the floor. This is one of the most important principles of the dance. Then, for step five, raise both of your heels from the floor and slap your hip. Like this!”

“Kick your right paw sidewards, old back-fence baritone, and keep on slapping your hip. Now run along and practice your steps in someone’s backyard. Little Ann must hurry and keep a dinner-date. See you at the 'Scandals’”

In 1927, Felix was at the height of his popularity but would soon fall quickly. The advent of sound brought new cartoon characters. Felix stayed mute and lost his release with Educational Pictures in 1928. Some sound cartoons were released on a States Rights basis in 1929-30 but that was Felix’s real last gasp. A Mickey-esque Felix appeared in three cartoons for Van Beuren in 1936 before the “bag-of-tricks” Felix in made-for-TV cartoons that were churned out in the last ‘50s. But the real Felix belongs to the silent film era, a great a star in his own way as Chaplin and Keaton—and even an energetic Broadway dancer named Ann Pennington.

The January 1927 edition of Photoplay magazine included a two-page spread of Felix dancing the Black Bottom with the woman who popularised it, Ann Pennington. She danced in the Ziegfeld Follies and George White Scandals. But age has a habit of creeping up on dancers and Pennington finally retired during World War Two—and spent much of the rest of her life on welfare, living in rooming hotels on (appropriate for a dancer, I suppose), 42nd Street.

The Black Bottom was one of her dances; butt-slapping dances crop up occasionally in the cartoons of the New York studios in the early ‘30s. In Photoplay, she’s shown teaching it to Felix who, though he has a black bottom, never did the dance in any cartoons that I can recall off-hand. Here are the photos from Photoplay, with the text that accompanies each picture.

Felix decides that the Charleston is passé and goes to Ann Pennington for a lesson in the Black Bottom. In the first step, Ann points her left foot to the side, raising the left heel from the floor, bending both knees and slanting her body backwards

Second step. “Now, Felix,” says Ann, “straighten the body, lower the left heel and point your toe up from the floor. And, Felix, sing that song, ‘The Black Bottom of the Swanee River, sometimes likes to shake and shiver.’ A little more pep, please!”

“Come on, cat! All set for the third step. Face forward, Felix, and bend that left knee slightly, pointing the left paw toward the floor. This is the way we make ‘em sit up and take notice when we dance the ‘Black Bottom’ in Mr. White's ‘Scandals’.”

“Snap into the fourth step, funny feline! Stamp that left mouse-catcher on the floor and bend that left knee. Stamp it good and hard. And sing that song—‘They call it Black Bottom, a new twister. They sure got ‘em, oh sister!’”

“Now, Mr. Cream and Catnip Man, after stamping forward, drag the left paw back across the floor. This is one of the most important principles of the dance. Then, for step five, raise both of your heels from the floor and slap your hip. Like this!”

“Kick your right paw sidewards, old back-fence baritone, and keep on slapping your hip. Now run along and practice your steps in someone’s backyard. Little Ann must hurry and keep a dinner-date. See you at the 'Scandals’”

In 1927, Felix was at the height of his popularity but would soon fall quickly. The advent of sound brought new cartoon characters. Felix stayed mute and lost his release with Educational Pictures in 1928. Some sound cartoons were released on a States Rights basis in 1929-30 but that was Felix’s real last gasp. A Mickey-esque Felix appeared in three cartoons for Van Beuren in 1936 before the “bag-of-tricks” Felix in made-for-TV cartoons that were churned out in the last ‘50s. But the real Felix belongs to the silent film era, a great a star in his own way as Chaplin and Keaton—and even an energetic Broadway dancer named Ann Pennington.

Labels:

Felix the Cat

Friday, 3 April 2015

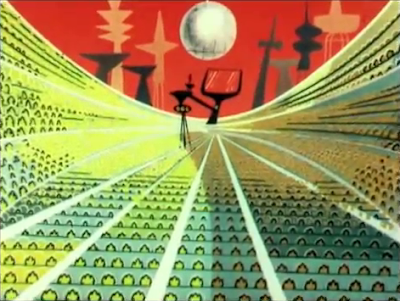

Joe Montell's Mars

Some opening backgrounds from the great John Sutherland industrial film “Destination Earth.” Joe Montell handled all the backgrounds from layouts by Tom Oreb and Vic Haboush. I believe Oreb did the Martian scenes and Haboush the Earth ones. Sorry they’re so small and fuzzy.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Montell had been a background artist for Tex Avery at MGM until the Avery unit closed in 1953. He went on to Hanna-Barbera and then worked for Jay Ward in Mexico. You can read more about Montell’s career HERE.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Montell had been a background artist for Tex Avery at MGM until the Avery unit closed in 1953. He went on to Hanna-Barbera and then worked for Jay Ward in Mexico. You can read more about Montell’s career HERE.

Labels:

John Sutherland

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)