How did Jack Benny find time to go on the air?

He always seems to have been all over North America, attending fund-raisers or banquets or some similar thing.

Here’s a 1950 newspaper story about Benny meeting up with a bunch of reporters. In New York City. On his birthday. He was in New York for a benefit for the Heart Fund and had broadcast a couple of his radio shows from the city. It claims he ad-libbed a speech at a lunch honouring him. It could be true. But I can’t help but thing he didn’t walk in unprepared.

Radio Ringside

Distributed by International News Service

By JOHN M. COOPER

New York, Feb. 16 —(INS)— Jack Benny claims he’s no good with the ad-libs and is lost without a script full of jokes.

He admits quite cheerfully all the charges that Fred Allen has made to that effect. He will even quote Allen’s remarks.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that Benny can make a very funny ad-lib speech, and in fact has done so many times during the last few weeks while he has been visiting New York.

Yesterday, just before taking the train back to Los Angeles, he outdid himself at a “Banshee" luncheon honoring Bill Hutchinson, Washington bureau chief for International News Service. The Banshees are a group of top newspapermen, and a lot of famous people were on hand to celebrate Hutchinson’s 30th anniversary with INS.

It was also Benny’s 56th birthday, and the Banshees took the opportunity to make him a life member of their organization. They gave him a handsome plaque to prove it. So Benny made a speech.

He said he had made a lot of speeches in behalf of such things as the Heart fund, the March of Dimes, etc., and it was nice, for a change, not to have to appeal for funds.

“Of course,” Jack added, “if any of you want to contribute something, it’s okay with me. It’s a long, expensive trip back to Los Angeles.”

Some photographers who were taking pictures moved him to remark that he hadn’t yet seen any pictures of himself in the New York papers.

“Except,” he added, “that I finally found one in the Daily Worker. But I still can’t understand how they got that hammer and sickle in my hand.”

Benny remarked that the government tax experts haven’t yet decided whether to approve his famous capital gains deal, under which he left NBC for CBS. He explained:

“I said it was a capital gains deal. They said the gain should go to the capital, which is in Washington.”

As for the plaque given him by the Banshees, he wondered whether he would have to give it to CBS Board Chairman William S. Paley.

“When he bought me,” said Benny, “he bought everything.”

Jack even tossed in a remark for the Waldorf Astoria hotel, where the luncheon was held. He said:

“It’s a nice hotel, but I can’t afford to stay in it. It’s the only hotel I know where you have to be shaved before they let you in the barber shop.”

Sunday, 5 April 2015

Saturday, 4 April 2015

Felix and the Flapper

Sure, Betty Boop somewhat epitomised the Roaring ‘20s (even they were dead by the time she debuted), but the cartoon character who hung out with flappers was Felix the Cat. Well, one flapper, anyway.

The January 1927 edition of Photoplay magazine included a two-page spread of Felix dancing the Black Bottom with the woman who popularised it, Ann Pennington. She danced in the Ziegfeld Follies and George White Scandals. But age has a habit of creeping up on dancers and Pennington finally retired during World War Two—and spent much of the rest of her life on welfare, living in rooming hotels on (appropriate for a dancer, I suppose), 42nd Street.

The Black Bottom was one of her dances; butt-slapping dances crop up occasionally in the cartoons of the New York studios in the early ‘30s. In Photoplay, she’s shown teaching it to Felix who, though he has a black bottom, never did the dance in any cartoons that I can recall off-hand. Here are the photos from Photoplay, with the text that accompanies each picture.

Felix decides that the Charleston is passé and goes to Ann Pennington for a lesson in the Black Bottom. In the first step, Ann points her left foot to the side, raising the left heel from the floor, bending both knees and slanting her body backwards

Second step. “Now, Felix,” says Ann, “straighten the body, lower the left heel and point your toe up from the floor. And, Felix, sing that song, ‘The Black Bottom of the Swanee River, sometimes likes to shake and shiver.’ A little more pep, please!”

“Come on, cat! All set for the third step. Face forward, Felix, and bend that left knee slightly, pointing the left paw toward the floor. This is the way we make ‘em sit up and take notice when we dance the ‘Black Bottom’ in Mr. White's ‘Scandals’.”

“Snap into the fourth step, funny feline! Stamp that left mouse-catcher on the floor and bend that left knee. Stamp it good and hard. And sing that song—‘They call it Black Bottom, a new twister. They sure got ‘em, oh sister!’”

“Now, Mr. Cream and Catnip Man, after stamping forward, drag the left paw back across the floor. This is one of the most important principles of the dance. Then, for step five, raise both of your heels from the floor and slap your hip. Like this!”

“Kick your right paw sidewards, old back-fence baritone, and keep on slapping your hip. Now run along and practice your steps in someone’s backyard. Little Ann must hurry and keep a dinner-date. See you at the 'Scandals’”

In 1927, Felix was at the height of his popularity but would soon fall quickly. The advent of sound brought new cartoon characters. Felix stayed mute and lost his release with Educational Pictures in 1928. Some sound cartoons were released on a States Rights basis in 1929-30 but that was Felix’s real last gasp. A Mickey-esque Felix appeared in three cartoons for Van Beuren in 1936 before the “bag-of-tricks” Felix in made-for-TV cartoons that were churned out in the last ‘50s. But the real Felix belongs to the silent film era, a great a star in his own way as Chaplin and Keaton—and even an energetic Broadway dancer named Ann Pennington.

The January 1927 edition of Photoplay magazine included a two-page spread of Felix dancing the Black Bottom with the woman who popularised it, Ann Pennington. She danced in the Ziegfeld Follies and George White Scandals. But age has a habit of creeping up on dancers and Pennington finally retired during World War Two—and spent much of the rest of her life on welfare, living in rooming hotels on (appropriate for a dancer, I suppose), 42nd Street.

The Black Bottom was one of her dances; butt-slapping dances crop up occasionally in the cartoons of the New York studios in the early ‘30s. In Photoplay, she’s shown teaching it to Felix who, though he has a black bottom, never did the dance in any cartoons that I can recall off-hand. Here are the photos from Photoplay, with the text that accompanies each picture.

Felix decides that the Charleston is passé and goes to Ann Pennington for a lesson in the Black Bottom. In the first step, Ann points her left foot to the side, raising the left heel from the floor, bending both knees and slanting her body backwards

Second step. “Now, Felix,” says Ann, “straighten the body, lower the left heel and point your toe up from the floor. And, Felix, sing that song, ‘The Black Bottom of the Swanee River, sometimes likes to shake and shiver.’ A little more pep, please!”

“Come on, cat! All set for the third step. Face forward, Felix, and bend that left knee slightly, pointing the left paw toward the floor. This is the way we make ‘em sit up and take notice when we dance the ‘Black Bottom’ in Mr. White's ‘Scandals’.”

“Snap into the fourth step, funny feline! Stamp that left mouse-catcher on the floor and bend that left knee. Stamp it good and hard. And sing that song—‘They call it Black Bottom, a new twister. They sure got ‘em, oh sister!’”

“Now, Mr. Cream and Catnip Man, after stamping forward, drag the left paw back across the floor. This is one of the most important principles of the dance. Then, for step five, raise both of your heels from the floor and slap your hip. Like this!”

“Kick your right paw sidewards, old back-fence baritone, and keep on slapping your hip. Now run along and practice your steps in someone’s backyard. Little Ann must hurry and keep a dinner-date. See you at the 'Scandals’”

In 1927, Felix was at the height of his popularity but would soon fall quickly. The advent of sound brought new cartoon characters. Felix stayed mute and lost his release with Educational Pictures in 1928. Some sound cartoons were released on a States Rights basis in 1929-30 but that was Felix’s real last gasp. A Mickey-esque Felix appeared in three cartoons for Van Beuren in 1936 before the “bag-of-tricks” Felix in made-for-TV cartoons that were churned out in the last ‘50s. But the real Felix belongs to the silent film era, a great a star in his own way as Chaplin and Keaton—and even an energetic Broadway dancer named Ann Pennington.

Labels:

Felix the Cat

Friday, 3 April 2015

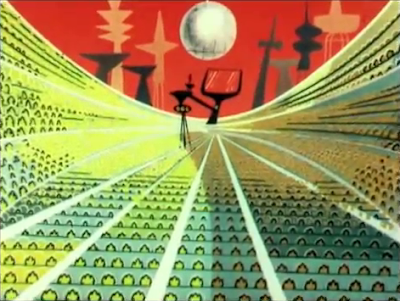

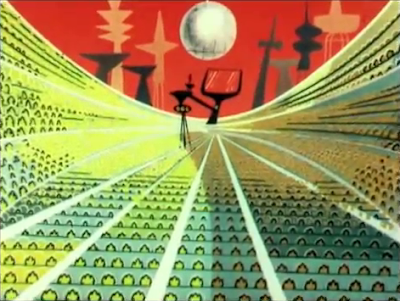

Joe Montell's Mars

Some opening backgrounds from the great John Sutherland industrial film “Destination Earth.” Joe Montell handled all the backgrounds from layouts by Tom Oreb and Vic Haboush. I believe Oreb did the Martian scenes and Haboush the Earth ones. Sorry they’re so small and fuzzy.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Montell had been a background artist for Tex Avery at MGM until the Avery unit closed in 1953. He went on to Hanna-Barbera and then worked for Jay Ward in Mexico. You can read more about Montell’s career HERE.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Montell had been a background artist for Tex Avery at MGM until the Avery unit closed in 1953. He went on to Hanna-Barbera and then worked for Jay Ward in Mexico. You can read more about Montell’s career HERE.

Labels:

John Sutherland

Thursday, 2 April 2015

An Old Bag

Screwy Squirrel’s reaction when the rich, wart-faced dowager wants to buy him from a pet shop for Lonesome Lenny.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Reality.

.png)

The truth.

.png)

Ray Abrams, Preston Blair, Walt Clinton and Ed Love animate Screwy’s farewell performance.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Reality.

.png)

The truth.

.png)

Ray Abrams, Preston Blair, Walt Clinton and Ed Love animate Screwy’s farewell performance.

Labels:

MGM,

Screwy Squirrel,

Tex Avery

Wednesday, 1 April 2015

The Fred Allen Robot

Had the Jack Benny-Fred Allen “feud” been going on radio in 1934, the idea of a robotic Fred Allen would have been good for some gags. Additionally, the 1944 version of the real Allen would no doubt find a way to liken it to sponsors or NBC vice-presidents.

But there actually was a robot Fred Allen. It was on display at the 1934 World’s Fair. It’s fate today is unknown. Here’s a story from the Dobbs Ferry Register, June 15, 1934. The photo accompanied the story.

Wise-Cracking Robot With Human Expression Goes To World’s Fair

New York—(Special) — Simulating human mannerisms, facial expressions and gestures, a mechanical man, the first in which these human traits have been attempted, is on its way to Chicago where it will have a prominent place at the new World’s Fair.

The 1934 model mechanical man bears no resemblance to the stiff, machine-like robots of earlier vintages.

His speech has been vastly improved and he has been madę to look like a human being. He talks, moves his head, smiles, shows his teeth, raises his eyebrows, rolls his eyes, and chuckles.

In endeavoring to build a mechanical man resembling a human being, the inventors obtained permission from Fred Allen, the radio comedian, to attempt to reproduce his head, facial expressions, and voice.

A corps of sculptors and electrical engineers worked nearly three months to complete the mechanical Fred Allen which was built by the Ivel Corporation of New York. The mechanical “brain” was supplied by K. D. Andrews, said to be the only robot builder in this country. The face which is madę of a patented flexible rubber was designed by William Herrschaft, a sculptor.

The mechanical Fred Allen is the first comedian among robots for he wise-cracks and makes facial grimaces very much like the real Fred Allen. At the World’s Fair he will perform continuously as a guest of the Bristol-Myers Company in their Ipana exhibit in the General Exhibits Building where he will be known as “The Ipanaman.”

But there actually was a robot Fred Allen. It was on display at the 1934 World’s Fair. It’s fate today is unknown. Here’s a story from the Dobbs Ferry Register, June 15, 1934. The photo accompanied the story.

Wise-Cracking Robot With Human Expression Goes To World’s Fair

New York—(Special) — Simulating human mannerisms, facial expressions and gestures, a mechanical man, the first in which these human traits have been attempted, is on its way to Chicago where it will have a prominent place at the new World’s Fair.

The 1934 model mechanical man bears no resemblance to the stiff, machine-like robots of earlier vintages.

His speech has been vastly improved and he has been madę to look like a human being. He talks, moves his head, smiles, shows his teeth, raises his eyebrows, rolls his eyes, and chuckles.

In endeavoring to build a mechanical man resembling a human being, the inventors obtained permission from Fred Allen, the radio comedian, to attempt to reproduce his head, facial expressions, and voice.

A corps of sculptors and electrical engineers worked nearly three months to complete the mechanical Fred Allen which was built by the Ivel Corporation of New York. The mechanical “brain” was supplied by K. D. Andrews, said to be the only robot builder in this country. The face which is madę of a patented flexible rubber was designed by William Herrschaft, a sculptor.

The mechanical Fred Allen is the first comedian among robots for he wise-cracks and makes facial grimaces very much like the real Fred Allen. At the World’s Fair he will perform continuously as a guest of the Bristol-Myers Company in their Ipana exhibit in the General Exhibits Building where he will be known as “The Ipanaman.”

Labels:

Fred Allen

Tuesday, 31 March 2015

Sheep Wrecked Pan

The camera pans over a long Fernando Montealegre background drawing after an establishing shot in the Mike Lah-directed “Sheep Wrecked” (released in 1958). I’ve had to break it down into two graphic files because it’s so long, and the camera moves in on it slightly about halfway through the pan.

The drawing is from an Ed Benedict layout. Monty and Benedict’s work wasn’t quite as stylised at Hanna-Barbera, where they were working when this cartoon appeared in theatres.

The drawing is from an Ed Benedict layout. Monty and Benedict’s work wasn’t quite as stylised at Hanna-Barbera, where they were working when this cartoon appeared in theatres.

Labels:

MGM

Monday, 30 March 2015

Out You Go Once And For All

Who’s going to throw whom out of the old lady’s house—Bugs Bunny or Sylvester the dog (played by Tedd Pierce)? The answer keeps changing in “Hare Force” (1944), a cartoon declared “a howl” by Film Daily.

The dog picks up Bugs and walks toward the door. But turns things around and picks up the dog and heads in the same direction. I like how the switch is quickened simply by having multiple dogs and rabbits in a frame, instead of having two per frame.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Then the characters exchange places. The expressions are great; but you’ll never see them unless you freeze-frame the cartoon.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

They switch back.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Who wins? Bugs and the dog. They throw out the old lady (played by Bea Benaderet).

Manny Perez gets the rotating animation credit.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Then the characters exchange places. The expressions are great; but you’ll never see them unless you freeze-frame the cartoon.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

They switch back.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Who wins? Bugs and the dog. They throw out the old lady (played by Bea Benaderet).

Manny Perez gets the rotating animation credit.

Labels:

Friz Freleng,

Warner Bros.

Sunday, 29 March 2015

Johnny Green

Phil Harris was the most popular bandleader on the Jack Benny radio show but the most celebrated may have been Johnny Green.

Green’s fame doesn’t come from leading an orchestra but from his composing. He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1972 for such standards as “Body and Soul,” “Coquette” and his movie scores for “Easter Parade,” “An American in Paris” and “West Side Story” (later in life, he preferred to be known as “John Green.”

Here’s a piece on him from the radio column Brooklyn Eagle of October 6, 1935. Of interest to Benny fans will be the reference to Michael Bartlett, the singer who left the show a few weeks into the 1935-36 season. None of the shows with him are known to exist.

Green’s fame doesn’t come from leading an orchestra but from his composing. He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1972 for such standards as “Body and Soul,” “Coquette” and his movie scores for “Easter Parade,” “An American in Paris” and “West Side Story” (later in life, he preferred to be known as “John Green.”

Here’s a piece on him from the radio column Brooklyn Eagle of October 6, 1935. Of interest to Benny fans will be the reference to Michael Bartlett, the singer who left the show a few weeks into the 1935-36 season. None of the shows with him are known to exist.

Out of a Blue Sky

Radiography of Johnny Green, Graduate of Fair Harvard—Studio Happenings

By JO RANSON

RADIOGRAPHIES . . . the victim of our microscope today, ladies and gentleman, is Johnny Green, Jack Benny’s new music-master . . . the college boy gone Broadway . . . and in a mighty big way . . . the graduate of fair Harvard who is more at home on Tin Pan Alley than he is at the polo matches . . . Johnny’s every day conversation is an accurate gauge of his crazy-quilt background . . . “Listen, Toots, cahn’t you gimme haalf (with a very broad “a”) an octave higher on those horns?"

He pleads earnestly to his brass section in rehearsal . . . Massa Jack "Ebenezer" Benny may be the "frustrated fiddler," but our hero, Johnny Green, is the frustrated dialectician . . . that deliciously-funny Sunday night program is full of suppressed desires and you don't have to be a student of Freud or Jung to see it . . . Mary aches to be a poet . . . Mike Bartlett wants to read the commercial announcements and Don Wilson wants to sing . . . a house full of unhappiness, a Russian mansion, no less . . . but back to our hero, we must go . . Green is known as a composer . . . he always wears a French beret when he is writing new tunes and it doesn't seem to affect him for he has produced such big winners as "Body and Soul" (wotta a tune! wotta a tune!) and "I Cover the "Waterfront" (little resemblance, however, to the Max Miller book) . . . he is one of the shrewdest businessmen among the radio artists . . . what else would you expect from a Harvard Bachelor of Economics . . . he is an official of Mr. William S. Paley’s network (that's the Columbia Broadcasting System, in case you don't know), holding down his job as Columbia's musical adviser, although this season finds him broadcasting exclusively on one of the ace comedy shows of Mr. Merlin H. Aylesworth’s up-and-coming group of stations (National Broadcasting Company, if you please) . . . you ask Johnny Green how he is getting along his serious composing and he answers by querying if you have heard the latest one about the two, etc. . . . whether you have or not, he proceeds to tell it to you in the most butchering dialect these ears have ever heard . . . Lou Holtz couldn't do it any better . . . Johnny is married . . . tall . . . dark-haired . . . brown-eyed . . . his hair is always too long . . . of course, that's what the boys on the Main Steam and Radio Row call showmanship . . . a maestro, it seems, is always supposed to appear as if he were cheating the barber . . . otherwise he would look just like the rest of us mortals . . . he is definitely a member of Gotham's "smart set," the entrance requirements to which are talent and not money or family . . . get him in front of an orchestra and Johnny is no longer "the old smoothie" . . . gone is the Harvard poise (or should it be pose?) . . . he screws his countenance into amazing shapes and almost terrifying grimaces result . . . he began his career as an arranger for the highly-successful (financially, of course) Lombardos . . . later, he was musical boss of the Paramount theater here in Brooklyn . . we saw a lot of the guy then . . . that was back in the dim and distant days when stage shows were part of show business . . . a gentleman with what is so freely referred to as "a grand sensayuma" (and in this case it is genuine), Green manages to work his appreciation of fun and funny business into his arrangements . . . once in a while he is accused of making his orchestrations a touch complicated . . . but that is the desire for speaking in exaggerated dialect cropping up again . . . apparently he is saying it with music . . . right now Johnny thinks he is a little overweight and hopes to get rid of some of his excess poundage while he is out on the West Coast . . . how does he hope to accomplish it? . . . by reclining on the beach at Santa Monica . . . if Jack Benny is smart, he will build up Green as a wise-guy . . . because Johnny is an expert at repartee . . . but he is too well-behaved to bore you with his flippancy outside of the studio.

Radiography of Johnny Green, Graduate of Fair Harvard—Studio Happenings

By JO RANSON

RADIOGRAPHIES . . . the victim of our microscope today, ladies and gentleman, is Johnny Green, Jack Benny’s new music-master . . . the college boy gone Broadway . . . and in a mighty big way . . . the graduate of fair Harvard who is more at home on Tin Pan Alley than he is at the polo matches . . . Johnny’s every day conversation is an accurate gauge of his crazy-quilt background . . . “Listen, Toots, cahn’t you gimme haalf (with a very broad “a”) an octave higher on those horns?"

He pleads earnestly to his brass section in rehearsal . . . Massa Jack "Ebenezer" Benny may be the "frustrated fiddler," but our hero, Johnny Green, is the frustrated dialectician . . . that deliciously-funny Sunday night program is full of suppressed desires and you don't have to be a student of Freud or Jung to see it . . . Mary aches to be a poet . . . Mike Bartlett wants to read the commercial announcements and Don Wilson wants to sing . . . a house full of unhappiness, a Russian mansion, no less . . . but back to our hero, we must go . . Green is known as a composer . . . he always wears a French beret when he is writing new tunes and it doesn't seem to affect him for he has produced such big winners as "Body and Soul" (wotta a tune! wotta a tune!) and "I Cover the "Waterfront" (little resemblance, however, to the Max Miller book) . . . he is one of the shrewdest businessmen among the radio artists . . . what else would you expect from a Harvard Bachelor of Economics . . . he is an official of Mr. William S. Paley’s network (that's the Columbia Broadcasting System, in case you don't know), holding down his job as Columbia's musical adviser, although this season finds him broadcasting exclusively on one of the ace comedy shows of Mr. Merlin H. Aylesworth’s up-and-coming group of stations (National Broadcasting Company, if you please) . . . you ask Johnny Green how he is getting along his serious composing and he answers by querying if you have heard the latest one about the two, etc. . . . whether you have or not, he proceeds to tell it to you in the most butchering dialect these ears have ever heard . . . Lou Holtz couldn't do it any better . . . Johnny is married . . . tall . . . dark-haired . . . brown-eyed . . . his hair is always too long . . . of course, that's what the boys on the Main Steam and Radio Row call showmanship . . . a maestro, it seems, is always supposed to appear as if he were cheating the barber . . . otherwise he would look just like the rest of us mortals . . . he is definitely a member of Gotham's "smart set," the entrance requirements to which are talent and not money or family . . . get him in front of an orchestra and Johnny is no longer "the old smoothie" . . . gone is the Harvard poise (or should it be pose?) . . . he screws his countenance into amazing shapes and almost terrifying grimaces result . . . he began his career as an arranger for the highly-successful (financially, of course) Lombardos . . . later, he was musical boss of the Paramount theater here in Brooklyn . . we saw a lot of the guy then . . . that was back in the dim and distant days when stage shows were part of show business . . . a gentleman with what is so freely referred to as "a grand sensayuma" (and in this case it is genuine), Green manages to work his appreciation of fun and funny business into his arrangements . . . once in a while he is accused of making his orchestrations a touch complicated . . . but that is the desire for speaking in exaggerated dialect cropping up again . . . apparently he is saying it with music . . . right now Johnny thinks he is a little overweight and hopes to get rid of some of his excess poundage while he is out on the West Coast . . . how does he hope to accomplish it? . . . by reclining on the beach at Santa Monica . . . if Jack Benny is smart, he will build up Green as a wise-guy . . . because Johnny is an expert at repartee . . . but he is too well-behaved to bore you with his flippancy outside of the studio.

Labels:

Jack Benny

Saturday, 28 March 2015

We're Not in Kansas Any More, We're in Ottawa

Canadian content rules have resulted in many things, including endless playings of Anne Murray’s “Snowbird” on the radio in the early ‘70s. They also brought about a cartoon series that has its charms for some despite very limited animation.

Canadian content rules have resulted in many things, including endless playings of Anne Murray’s “Snowbird” on the radio in the early ‘70s. They also brought about a cartoon series that has its charms for some despite very limited animation.

“The Tales of the Wizard of Oz” was produced in 1961 by Crawley Films of Ottawa for Videocraft International. By the mid-1950s, Crawley was the largest maker of filmed commercials in Canada, had created industrial shorts and, by 1957, worked out a co-production deal with the CBC and BBC for a TV series called “R.C.M.P.” Eventually the company expanded into features and ran into money trouble. You can read more about the company and its founder HERE.

Videocraft eventually became Rankin-Bass Productions. So much has been written about the company, I need not say much more (other than to suggest buying Rick Goldschmidt’s books on the studio). Rick explains that Videocraft International was begun in 1959, and trade ads show it was one of three subsidiaries of Video Crafts Inc. Broadcasting-Telecasting, in its July 6, 1953 edition, mentioned that Rankin had quit as head of ABC-TV's graphic arts department to join Video Crafts. Variety reported some history in its weekly issue of June 25, 1958:

Japanese Telefilmers Go Into Production On TV Blurbs for U.S. UseVideocraft’s deal gave birth to a series featuring what was originally called “dimensional puppetry;” a form of stop-motion animation. Here’s Variety to talk about it in the March 15, 1961. And this is where we find the first mention of the “Oz” cartoons.

Japanese animation and stop-motion producers have produced their first tv blurbs for American consumption. Via Paris & Peart, Illinois Baking, A& P and Vanity Fair Facial Tissues account for four full-length blurbs and a show opening and closing. Six of the major animators and puppet filmers in Japan formed recently, into the Japan Animation Producers Assn. and are doing their U. S. biz here via Video Crafts Inc.

Art Rankin topper of Video Crafts (begun in 1950 as a tv graphics house before expanding into the general commercial field a few years later), said that production on the Paris & Peart blurbs was begun approximately six weeks ago. His contention is that the Japanese are excellent animators and that most of their work shows a different approach from domestic animation styles. Moreover, animation production in Japan, done in just about the same amount of time as here regardless of the trans-Pacific-continental shipping, is generally one-third less expensive than American-made product.

Rankin's organization, holding an exclusive tie-up with the new Oriental outfit, has assigned them production of new tv program animations. Show, broken into three-and-a-half minute segments for the most part is being called "Willy McBean & His Magic Machine." Ultimately, the Japanese telefilmers will have 100 ready for syndication. Rankin also bought 60 animated and puppet films that had already been produced for Japan. They will be cut from half-hour lengths into five-minute segs and Rankin is doing new sound tracks for all of them. [omit remainder of the article]

‘Pinocchio’ Tees Off Videocraft's New Approach to Vidkid EntriesVideocraft’s original intention was to have “Oz” done in Japan. But plans changed. This is from the weekly Variety of June 14, 1961.

A new approach to children's programming—though actually it's the oldest of all kiddie forms—has been undertaken by Videocraft Productions, a firm heretofore confined to production of commercials and industrial pix.

The approach is the creation of series based on fairy tales and other traditional kidstories. First show out of the Videocraft hopper is "The New Adventures of Pinocchio," series of 130 five-minute segments filmed in a new process called "Anamagic," [sic] utilizing animated, puppets. Next up will be an animated series of five-minute segments, "Tales of the Wizard of Oz," employing the original Frank Baum characters. Both shows are syndication entries; "Pinocchio" is already sold in over 20 markets, with Videocraft handling its own sales.

Videocraft's Canada TV Animated SeriesAnd why did plans change? Simple. Canadian laws were changed all but guaranteeing a spot on television for any Canadian-made animation. I suspect Arthur Rankin wasn’t one to turn down a guaranteed sale. Plans to do the soundtracks in New York changed, too. What was Allen Swift’s loss was Paul Kligman’s gain (it’s sheer speculation on my part that Swift would have been cast, but he seemed to voice all kind of cartoons and untolled commercials in New York at the time). Weekly Variety again, from July 26, 1961:

Videocraft Productions, already producing one animated series in Tokyo, has now slated another for Canada. Company has set a facilities deal with Crawley Studios in Toronto for production of 260 five-minute color episodes of "Tales of the Wizard of Oz," based on the original Frank Baum book.

As with "Pinocchio," Videocraft's Nippon production, the N. Y. company will supply the creative work, designs, characters, storyboards, scripts and soundtracks, while Crawley does the actual physical production.

‘55% Canadian Content’ Crawley's Big Plus in Wooing TintedThe names of the voice actors should be recognisable to any Rankin-Bass fan. Several can be heard in the stop-motion “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and even later on the TV Spider-Man cartoons produced by Grantray-Lawrence and Steve Krantz. And if I have to explain to you who James Doohan is, you’ll be attacked by Trekkies/Trekkers faking a Scottish accent.

The strongest factor, along with proximity, that won Crawley Films Ltd. here the 260-stanza color tv-film series "Wonderful Wizard of Oz" away from Japan was Board of Broadcast Governors' “55% Canadian content” rule. It comes fully into effect next year on all Canadian stations, CBC and indie.

Two pilots for the five-minute series were made in Japan for Vide[o]craft Intl. Inc. [sic], but Crawley got the nod for the $300,000-plus deal for world distribution. (It's actually for 130, with another 130 optioned.) BBG reportedly promised Videocraft a “55% Canadian” seal for its Japanese-made “Pinocchio” as well, if “Oz” was made in Canada.

BBG chairman Dr. Andrew Stewart is quoted as saying the concession was made to encourage formation of a Canadian animation industry. This is the first major cartoon series made in Canada. Three have been shot, three are in production and 40 are expected to be in the can by Oct. 31.

Crawley Films will do all the visuals, with soundtrack made at RCA-Victor studios in Toronto by Bernard Cowan Associates Inc., with Canadian actors Pegi Loder, Paul Kligman, Larry Mann, Alfie Scopp and James Doohan in leads, directed by Cowan. Thomas Glynn, vet Crawley director, is helming the visuals and all technicians are Canadian. So are five-of the six key animators and as many others of the 35 needed as can be hired in Canada, the rest to come from U. K. (Crawley has rounded up 25 so far.) Firm has had a small animation unit for years for its commercial films, headed by Vic Atkinson. Dickie Horn, w. k. U. K. animator, is another of the key men, who also include William Mason, Barry Nelson, Dennis Pyke and English-born Robert Dalton, all Canadians.

Story boards are being done by Tom Peters and Jules Bass, both of N. Y.; latter a member of Videocraft directorate. Script is based on the Frank Baum characters, partially renamed Rusty the Tin Man, Dandy the Cowardly Lion, Socrates the Straw Man. Dorothy and the Munchkins, however, remains the same.

The Willie McBean project and another planned by Videocraft soon after are quite interesting and we’ll try to get to them in a future post.

Friday, 27 March 2015

Hot and Cold Cat

The vile Jerry Mouse tortures Tom by freezing him then boiling him a phoney attempt to cure him of the measles (which he doesn’t have) in “Polka-Dot Puss” (1949).

.png)

.png)

Tom’s fake sneeze blows himself apart at the beginning of the cartoon.

.png)

.png)

The usual animators are at work: Ken Muse, Ray Patterson, Ed Barge and Irv Spence.

.png)

.png)

Tom’s fake sneeze blows himself apart at the beginning of the cartoon.

.png)

.png)

The usual animators are at work: Ken Muse, Ray Patterson, Ed Barge and Irv Spence.

Labels:

Hanna and Barbera unit,

MGM

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)