A few changes came to the Jack Benny radio show in the 1944-45 season, not all of them good. The worst was the fact the show’s ratings dropped. Various Hooper reports over the course of the season reveal the show was between number 10 and 15 much of the time—not in the top five like Benny had been not long before.

I always thought the reason for this was the change in sponsorship. Shows before the ‘44-‘45 season opened with Don Wilson happily expounding on the joys of Jell-O or Grape Nuts Flakes. You could picture him enthusiastically gobbling them down; only his loyalty to the sponsor stopped him from doing it in mid-commercial. With a new sponsor came a harsh, obsessively repetitious (and Wilson-less) opening ad. I don’t know about you, but I don’t like being shouted at for the first minute and a half of a comedy show. But it turns out there may have been another reason for the ratings drop, one out of the control of anyone on the Benny show.

But before we get to that, let us point out the Lucky Strike sponsorship and its hard-sell ads were not what was anticipated when Benny signed a deal with American Tobacco. And it turned out Benny

had to drop Grape Nuts. Here’s what

Broadcasting magazine announced in its edition of February 28, 1944.

Pall Mall Acquires Jack Benny Series

Comedian Understood to Get $25,000 Weekly for Show

AMERICAN CIGARETTE & Cigar Co., New York, will sponsor Jack Benny in his present 7-7:30 p.m. Sunday spot on NBC, beginning next fall, the comedian announced last Thursday. He has signed a three-year contract with the company to broadcast a weekly program for Pall Mall Cigarettes,

he stated, with his 10-year association with General Foods which he described as "10 of the happiest years of my career", coming to an end with the broadcast of June 11.

The Sunday evening period on NBC is controlled by Benny under the terms of his last contract with General Foods, a situation believed to be unique in radio. When the contract was signed the comedian received from NBC a letter specifying that should he not continue under the same sponsorship at the conclusion of the contract, he should have the right to turn that choice spot over to any other sponsor-as long as the company is acceptable to NBC.

Pay Boost Claimed

Financial details of the new contract were not disclosed but it is understood that the cigarette company will pay $25,000 for the program each week, that sum covering the orchestra and all other talent on the broadcast, which is produced and sold by Mr. Benny as a package. His current contract reportedly is for $22,500 weekly.

Benny’s season debut was October 1. But

Billboard magazine of September 2 reported on talk to plug a different tobacco (stop groaning at the pun). It said Benny might be hawking Lucky Strikes instead; “Reason given for change was scarcity of product.” But Florence Small wrote in a puff piece on Pall Malls (oh, another pun) in the July 3, 1950 edition of

Broadcasting that “American Tobacco Co. believed it [the Benny show] was too large a venture and reassigned it to Luckies.”

Deciding against listening to haranguing commercials wasn’t the only danger awaiting the Benny show. General Foods didn’t want to give up the 7-7:30 p.m. Sunday time slot so easily. Since it was Benny’s to keep on NBC, General Foods simply went to another network. And it put up some big-name competition against him. Here’s

PM’s take in a column of July 12, 1944.

HEARD AND OVERHEARD

Rough Going for Benny

A couple of weeks ago Jack Benny abandoned General Foods, after an association of about 10 years, to take another sponsor, Pall Mall. The parting was accompanied by all sorts of fulsome glad-handing on both sides, and Jack and Mary Livingstone took full-page ads in the trade press to express the pious hope that the end of a decade of business relations did not mean the end of a beautiful friendship.

Whether that hope is justified is a matter for considerable doubt. You need only consider these factors (and let us put them delicately so as not to hurt anyone’s feelings):

Benny, by agreement with NBC. retains personal control of the 7 o’clock Sunday evening time, one of the choicest spots in radio. Over the last 10 years General Foods spent millions for that time and might presumably be somewhat disgruntled that Benny inherited it instead of the company.

General Foods values that period so much that next Fall it is sponsoring a full hour variety program, from 7 to 8 p.m. Sundays, on CBS. (The new program will almost certainly cost more than the reported $20,000 a week-exclusive of radio time cost—that the company paid Benny. This would seem to indicate that Benny's switch to Pall Mall, for a reported $25,000 a week, was not primarily due to any unwillingness by General Foods to raise the ante.)

For its new program General Foods is using Kate Smith as m.c. You are welcome to offer any reason you choose for the selection of Kate Smith, but you might like to know what reason is generally accepted in the radio industry. It’s this:

Years ago, when Amos and Andy were a national institution, and when everyone thought they would remain unbeatable, Kate Smith went up against them when nobody else would.

The industry thought she was nuts, that she would be so badly outclassed that she would vanish from the air. What happened? Nothing much-she just murdered Amos and Andy, that's all.

Some years later, when Rudy Vallee was the biggest thing in radio, Kate went on the air against him. The same thing happened. She murdered Vallee.

She has proved twice, and proved conclusively, that she can cut even the toughest competition down to size. And I’m willing to bet that Benny will be the third victim.

I don't want anyone to suppose I am a Kate Smith devotee. I like her personally, and she can sing, but I can't stand that Ted Collins—his is one of the most irritating voices on the air—and the unblushing way they read those commercials is infuriating. But millions of people do like—even love-both of them, which is a very fine thing for General Foods.

I’ll stick with Benny, regardless, and watch with considerable interest what happens to his rating. Over the past year his program ranked around fifth in the Hooper list of the nation's 15 most popular programs. Well see where tie is next November.

—ARNOLD BLOM

Kate Smith may never have been a top 15 show like Benny’s, but she must have cut into his numbers. And it doesn’t appear to have helped either of them. For example, the November 15th edition of

Radio Audience pointed out Smith’s Pulse average in October (ratings in New York and New Jersey) dropped from her 1944 average of 23.9% to 10.7% for October, while Benny’s declined from a 1944 average of 37.6 to 31.7. And

Broadcasting of July 9, 1945 pointed out Smith had the most listeners per family tuned in of any show in Spring 1945 and she was number one among women. Still, the weekly Hooperatings showed Benny was in the top 15, where Smith was nowhere to be found.

Finally, General Foods surrendered.

Broadcasting announced on August 6, 1945 that Smith would be moved to Fridays at 8:30 p.m. in the fall; “Adventures of The Thin Man” filled the time slot for CBS the following season (and for General Foods’ Post Toasties).

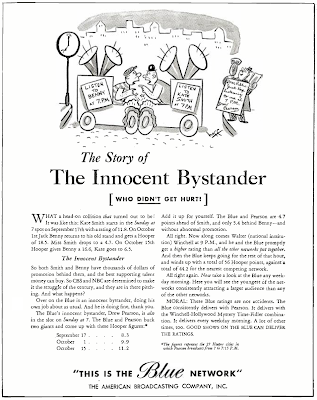

Meanwhile, some clever people at ABC (soon to drop the old designation of the Blue Network) made fun of the Benny-Smith ratings war in the trades. You can click on the ad to the right to see one of the full-pagers the network took out.

The people at the Benny show also took some action on their own in the following season to entice listeners. They developed a gimmick to get people to listen week after week: the I-Can’t-Stand-Jack-Benny-Because contest. The show benefitted from Dennis Day returning from the Navy (he had been on an AFRS assignment in Hollywood for the latter part of the war). And new secondary characters were added: Mr. Kitzel (Artie Auerbach, reworked from “The Al Pearce Show”), Polly the parrot (Mel Blanc), the next-door-neighbour Colmans, the phone operators (Bea Benaderet and Sara Berner), which all gave the show a boost.

As a side note, Benny took a light-hearted swipe on his first show for General Foods in 1934. While he introduced himself for years with “Jell-O, again,” on his initial show for the dessert, he chirped “Jell-O, everybody!” making fun of Smith’s well-known “Hello, everybody!” greeting on her programme.

The change from General Foods to American Tobacco had an unexpected casualty. With the change, the Benny show was no longer broadcast in Canada. The CBC looked at airing the show with war messages substituted for the Lucky Strike commercials on its Trans-Canada Network of independently owned stations (

Broadcasting, Sept. 11, 1944) . But after the October 1st broadcast, the plan was cancelled because Benny could not guarantee Lucky Strikes would not mentioned during the programme outside of the commercials (

Broadcasting, Oct. 16, 1944). What’s unusual about this is the Benny show was running on the American Armed Forces Radio Service with all the mentions of Luckies edited out, and transcriptions were being broadcast in Britain with the references removed. But in Canada, all that editing wasn’t an option for some reason. And, as

Broadcasting added: “In Canada the granting of sustaining privileges to the show brought opposition from the advertising and broadcasting industry. It was felt a precedent was being set under which any popular show could demand free time on a Canadian network because of popularity.” So Canadians had to listen to Benny for years on American border stations.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)