Popular culture can be a funny thing. A man can spend his life heard prominently announcing awards telecasts, commercials for big-name products, at least one incarnation of Walt Disney’s Sunday night show, but then become known for three words—“Danger Will Robinson.”

Will Robinson, known in real life as Bill Mumy, has passed on word on Facebook that Dick Tufeld, the voice of the robot on ‘Lost in Space,’ has passed away.

There was actually a time you could see Tufeld instead of hear him. He was a noon-hour newscaster at KABC in 1955 (soon moved to the 11 p.m. slot where he also did commentary) and hosted ‘Dick Tufeld’s Sports Page’ and ‘Focus on Los Angeles,’ a public affairs show. But his rich, smooth voice could have sold Barack Obama to Newt Gingrich. So, he went into commercial and announcing work. Disney hired him. So did Warner Bros. for the original ‘Bugs Bunny Show.’ Hanna-Barbera brought him in to say things like “The Jetsons. Brought to you by...” He was the announcer on ‘The Hollywood Palace.’ And the Oscars. And the Grammys. And the People’s Choice Awards. He told us Rice-A-Roni was the San Francisco Treat. He voiced obscure stuff, too. Jerry Fairbanks had him do an insert for the Bell Telephone industrial film ‘21st Century Calling’ set at the Seattle World’s Fair. The list goes on and on.

But he achieved fame amongst a certain segment of the population as part of the most unlikely TV comedy duo for his monotone comebacks to the increasingly campy Dr. Zachary Smith on ‘Lost in Space.’ Fan sites have Tufeld interviews on them, but here’s one I thought I’d pass on from the New York Daily News syndicate. It’s dated December 24, 1997.

Lost in Space voice gets heard again in the toy aisle

By David Bianculli

New York Daily News

WARNING! WARNING! Danger, Will Robinson! That does not compute!

Ask most people younger than 45 or so to identify the source of those phrases, and, because of their familiarity with either the original CBS series or its endless syndicated reruns, the answer is simple: The Robot from the 1965-68 sci-fi series Lost in Space, which airs daily on the Space channel.

However, ask them to identify the owner of that voice, and it’s a much trickier question. The answer is Dick Tufeld — and all of a sudden, just in time for Christmas, Tufeld’s voice is all over the place again.

He provides the Robot's voice in a new line of merchandising of classic Lost in Space stuff: talking mini-Robot key chains, for example, and even an ultra-cool, 11-inch Robot replica with a motorized base, moving arms and bubble head, and a voice chip that has Tufeld saying either “Danger, Will Robinson!” or “My sensors indicate an intruder is present!”

Well, my sensors indicate a hot holiday toy is present — and, indeed, the Trendmasters Lost in Space Robots have been selling fast and furiously. Tufeld, whose voice also introduced Zorro and, for years, Wonderful World of Disney, is understandably amused that the series is remembered that fondly — or even at all.

“This was not the strongest show anybody ever saw,” Tufeld said. But he knew, by speaking at colleges as early as the mid-70s and watching how college kids perked up when learning he had the Robot among his credits, just how resonant Lost in Space really was.

It was only a fluke, though, that made him the voice of the Robot. Tufeld had been hired as the show’s narrator by series creator Irwin Allen, but failed in his initial attempt to audition for the vocal role of the Robot.

Tufeld went in presuming Allen wanted a stiff-sounding, mechanical voice, but recalls Allen telling him, “My dear boy, that is exactly what I am not looking for! This is a highly advanced culture in the year 1997!” That, of course, was the year the show’s Jupiter 2 spaceship was launched.

After failing to please Allen with several low-key readings, Tufeld prepared to leave, then stopped and asked to try one more time.

“In my best mechanical, stiff, robot-ian kind of sound, I say, WARNING! DANGER! THAT DOES NOT COMPUTE!”

Allen’s eyes lit up, and Tufeld got the job.

Go figure. And if you want to please someone this year, go buy a Robot gift.

Tufeld was Irwin Allen’s announcer of choice and heard on a bunch of Allen’s shows of the ‘60s.

He had studied drama at Northwestern University. His friendly, resonant voice was perfect for radio. That’s where Tufeld resided prior to his television announcing career, which took off when “Space Patrol” debuted on KECA, ABC’s West Coast flagship, on March 9, 1950 (it became a radio show as well a few months later). My favourite radio work of his is with the future Fred Flintstone, Alan Reed, on “Falstaff Fables” (1950), featuring the Falstaff Openshaw character Reed did on Fred Allen’s show. Listen to one episode by clicking on the arrow. Try to resist going out to buy a Milky Way bar.

If you read commercials on the air for a living, you can only hope to sound as good as Dick Tufeld. Here’s one of his countless TV spots.

Late note: One of Dick’s grandchildren has pointed out in the comment section he voiced this full-length trailer for the Disney movie that kids begged their parents to let them see again and again: “Mary Poppins.”

A mid-‘60s issue of Screen Actors magazine notes Tufeld was an active SAG member, and part of joint talks between AFRTA and the Guild with commercial producers and ad agencies (on the committee with him were former radio actors Daws Butler, Vic Perrin, Ed Prentiss and Bud Hiestand).

Richard Norton Tufeld was born in Los Angeles on December 11, 1926 to Bentley J. and Margaret Tillie “Peggy” (Simons) Tufeld. His father, born in Russia as Bentzion Tuchfeld, came to the U.S. in 1913 and founded Western Office Furniture Company. His mother was Canadian according to Census figures but Russian (and named Tanya) according to naturalisation records. The two married in 1920. Tufeld grew up in Altadena and was, by all accounts, a thoughtful and likeable man. And 45 years after the fact, it’s evident to fans around the world no one could have been better at putting that duplicitous coward Dr. Smith in his place than the voice of Bill Mumy’s mechanical friend.

Sunday, 22 January 2012

Birds, Bees and Dennis Day

Dennis Day learned what everyone who has reached any level of fame has learned—your audience typecasts you. At times, that can be a good thing. If a star does something bad in real life, people refuse to believe it because they “know” him. But, professionally, it gets to be annoying after awhile. It certainly did to Dennis Day, it seems.

There’s a bit of irony in that. Day owed his career to the fact that Kenny Baker wearied of the same stereotype that Day did, and quit the Jack Benny radio show because of it. Day stuck with it. It was the wisest career decision. Not only did his role expand a bit on the Benny show—he got to show off his ability to do impressions—he ended up getting his own starring show on NBC. But, again, he was playing a watered down version of his character on the Benny show, a naïve, somewhat silly young man who was a little awkward around young women.

There’s a bit of irony in that. Day owed his career to the fact that Kenny Baker wearied of the same stereotype that Day did, and quit the Jack Benny radio show because of it. Day stuck with it. It was the wisest career decision. Not only did his role expand a bit on the Benny show—he got to show off his ability to do impressions—he ended up getting his own starring show on NBC. But, again, he was playing a watered down version of his character on the Benny show, a naïve, somewhat silly young man who was a little awkward around young women.

All this seems to have perturbed Dennis as he looked to expand his career past the narrow role people continued to want to see him in. He talked about it in the public press in 1950 as he pushed his new movie. Here’s one syndicated column.

In Hollywood

By ERSKINE JOHNSON

HOLLYWOOD, July 1 (NEA)—Maybe it won’t impress Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner, but Dennis Day, who has million-dollars tonsils, too, gets worry lines right under his widow’s peak whenever he thinks about Gloria de Haven.

The fancy forehead corrugation hasn’t a thing to do with bullfighters, either.

It seems that Gloria, a Hollywood doll who seldom gets a ting-a-ling when they’re looking for stained-glass window types, is about to throw a monkey wrench with SEX engraved on it smack into the middle of Dennis’ fan club of dear, old white-haired ladies.

When Gloria finishes hustling him soundly in Fox’s “I’ll Get By,” Dennis broods, the radio-confected pictures of him at an innocent lad in short pants will go boom-boom.

It’s worrying Dennis in the same way it would worry Gene Autry if he found himself in Mae West’s boudoir right in front of a million bubble-gum blowers.

Dennis looked around furtively and told me:

“I’m box office with those old girls. When I play theaters, they hobble down the aisles on crutches and smash into other people with their wheel chairs. Tired business men want to see Jane Russell. The white-haired gals who collect old-age pensions want to see me.”

Dennis says he’s been putting on the Little Lord Fauntleroy smile for years whenever somebody’s grandma yells for him.

He Knows, Girls

“They think I’m really the mother’s boy I play on Jack Benny’s radio show,” he sighed. “They don’t give me credit for knowing about the birds and bees.”

But there won't be any doubts when the picture is released, he’s sure.

“I get Gloria to make an honest man out of me by mentioning my mink farm. When Gloria hears me say ‘mink,’ she goes wild and screams, ‘Br-r-r-r-rother!’ Only the way Gloria bellows it, the word hasn’t got anything to do with National Brotherhood Week.”

Dennis can just see his picture turned to the wall in the parlors of the Day fans who look like Jack Benny in his Charley’s Aunt wig. He doesn’t think there’s a chance that it will be Gloria’s picture that gets the flip-over treatment. His over-sixty fans aren’t the kind who go around framing photos of girls in the Betty Grable league.

“I’ll Get By” is Dennis’ second movie—his No. 1 try was something called “Music in Manhattan” with Ann Shirley and Phil Terry about 10 years ago—and marks his first screen encounter with molten lipstick.

“Now,” he says, “I know how Shirley Temple felt when she got kissed for the first time.”

Dennis says that he’s been goggle-eyed about the radio public’s willingness to believe anything that comes bouncing over the air waves since he became the big load of whimsey on the Benny show in 1939. He complains:

“They think that Marie Wilson is a mental giant beside me. I have to go around saying, ‘I’m not a schmoe, I’m not a schmoe.’”

He’s lost count of the letters asking him about his wrestling, steam-fitting mother — “She’s really a demure lady”—and the age at which he was dropped on his noggin.

Even radio actors buttonhole him and whisper:

“Hey, just between you and me, is Jack Benny really that tight with a buck?”

Fair-Haired Boy

When Dennis isn’t peeking into Ulcerland about his first celluloid sex skirmish, he’s apt to go into a brown study about the Mother Macrees who haven’t seen him and think of him as a tall blond kid with hayseeds sticking out of his ears.

“Maybe,” says Dennis, “they’ll fall flat on their faces when they see me. Maybe the studio should have used the Larry Parks technique and hired Claude Jarman, Jr., or Butch Jenkins to play me.”

He says a lot of radio singers who have been trying to burst into movies for years fainted dead away and had to go to bed when word leaked out that he had turned down a chance to jump from “I’ll Get By” into RKO’s “Two Tickets to Broadway.”

One stopped him and said:

“Who are you to turn down pictures—Princess Aly Khan?”

Dennis has quite a reputation for his mimicry but nobody he imitates has ever threatened to give him a poke in the snoot. He’s not sure about Ronald Colman, though. When Colman first heard Dennis give out with the “I say, Bonita,” he turned to his wife and said:

“I say, Bonita, isn’t that a wonderful imitation of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.?”

Dennis hasn't figured it out yet.

“Maybe,” he says, “Colman doesn’t like Doug, Jr.”

“Princess Aly Khan” was better known as Rita Hayworth, who spent a fair chunk of time after her marriage refusing to work on pictures Columbia insisted on putting her in.

The following day, Hedda Hopper devoted her entire Sunday column to Dennis. You’ve got to love the way Hedda makes herself part of the story. And she gives a bit of insight into how canny Dennis was. There’s was a reason he inflicted “Clancy Lowered the Boom” on the Benny audience. He made money off it.

Dennis Day-He's Such a Boy

You'd never think that nostalgic tenor, that youthful innocence, that dumbjohn naivete came from a tough veteran in show business!

By HEDDA HOPPER

HOLLYWOOD—To millions of people Dennis Day is the eternal boy—a naive lad who says the things that most people only think, a lad who sings sweet songs in a tenor that calls forth nostalgic tears. And in recent years the public has come to think of Dennis as one of the world’s best comedians and imitators.

Every two years radio man Day shows his fans Dennis Day in the flesh through personal appearance tours across the nation.

And once in a blue moon Dennis makes a motion picture. This is his picture year. He’s co-starring in “I’ll Get By” at Twentieth Century-Fox with June Haver, Bill Lundigan and Gloria de Haven, and with such top stars as Clifton Webb, Jeanne Crain, Dan Dailey and Vic Mature doing specialty spots as background for his unique talents.

Won’t Sign Up

“You haven’t made a picture in six years,” I observed over our tea. “Why? It’s easier to let your public, see you on the screen than to go out on those killing personal appearance tours—and the money all goes out in tax anyway.”

“That’s true,’ said Dennis, “but you can’t find a producer who will let you off with one picture. They all want to sign you up for a baker’s dozen, and that I can’t do. Darryl Zanuck is the exception—when he wants you he’ll take you for a one-shot. He and Bill Perlberg don’t play that cards-to-the-chest game. They go out to make a top picture, and that's their first consideration.”

“Then you won’t make a p.a. tour this year?” I asked.

“No. I’ll spend my vacation time at Balboa,” he replied. “I’ve a house there and a little boat, and I’ll get 13 weeks rest. But I’ll go out on tour next year. The last time I went out we did six shows a day and I sing nine songs at each show. That’s work, sister. Toward the end of the tour I caught cold and lost my voice. I wanted to throw in the sponge, but you can’t let audiences down, so I came out and emceed the show in a croaking whisper until the voice got straightened out.”

His Name’s McNulty

Bronx-born Eugene Dennis McNulty is a fine looking lad in a drawing room. He wears with case and assurance clothes made by the best tailors. His ebony hair and heart-warming smile, a ready wit and flashes of temperamental fire make him a personality to remember. In private life the shy, star-struck boy of the radio becomes a man of modest reticence. He qualifies his success story repeatedly with use of the word “luck.”

“Luck has everything to do with it,” he said. “If Kenny Baker hadn’t pulled out of the Jack Benny show when he did, I’d probably be working away at the law. That’s what I wanted to be— a criminal lawyer. I find that branch absorbing.”

I wanted to know how a would-be criminal lawyer wound up as a world famous entertainer. “Didn’t that take some fancy footwork?” I asked.

“Oh, no. I’d always sung a bit. In the choir at St. Patrick’s cathedral when I was a small boy. I sang alto. Then when I was at Manhattan college we did some amateur shows with Larry Clinton’s orchestra. And I sang a couple of times on radio shows so in my spare time I’d fool about with recordings. I was recovering from an appendix operation when I made a recording of ‘Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair.’ Some fellows from a Canadian corporation were in the next room when I was cutting it and heard me. They bought it for $75. I ran home with the money and you can imagine the excitement. ‘A wonderful country this,’ my father said, ‘that pays you for singing. Why, when I sang in Ireland, they threw water at me!’”

It seems there were other singers among the McNultys. Dennis’ grandmother has a very fine voice and his mother is musical also.

“Mother played the tenement house piano—that’s what we call the accordion—at her own wedding,” Dennis explained. “She plays it now when we have a family get-together around the piano.”

So many McNultys came to California after Dennis arrived that they just bought they own apartment house and settled down. I wanted to know how many songs Dennis knew by heart.

Got to Keep Working.

He thought a moment. “It would run into the thousands I guess.” he smiled deprecatingly.

“You can’t help knowing a good many when you've been singing as long as I have. Then, you see, I take a singing lesson every day when I’m not making a picture. You can’t stand on your honors in life— you've got to keep working.”

Dennis sang a number of songs when he auditioned for the Jack Benny program—“I Never Knew Heaven Could Speak” and “Don’t Worry About Me” and “Yours Is My Heart Alone,” “A Pretty Girl Is Like A Melody,” “I’ll Follow My Secret Heart” and I don't know how many more. But it was “Jeanie” which caught Mary Livingstone’s fancy and which got him the chance to land in what he calls “the greatest showcase in the world”— the Benny show.

When Jack finally called Dennis’ name singling him out of a room full of hopeful aspirants, it was Dennis’ instant response “Yes, please,” which keyed the eternally fresh character he plays. He was nervous and reticent and his voice was higher than normal and a trifle breathless. Jack Benny a master showman, recognized his comedy value. “There’s our boy,” he told Mary. “We’ll play him just like that— a shy utterly sincere boy whose mother is somewhere in the offing all the time.”

Correct Psychology

Correct Psychology

Jack’s psychology was correct. Mrs. Patrick McNulty, who was Mary Grady of Carracastle, Ireland, has reared a family of four sons and a daughter to be proud of. It was his mother who introduced Dennis to Peggy Almquist, his wife and the mother of small Paddy and Denny. One brother is a doctor, another a teacher of electrical engineering at U.C.L.A., another is Denny’s business manager, and the fourth is in the pharmaceutical business. Dennis’ sister is married and the mother of four, and Grandma McNulty has nine grandchildren to fuss over, and she’s not yet 60.

Dennis has one great difficulty! There aren’t enough hours in a day for him He says he’s an eight-hour man when it comes to sleep and just must have it to keep his voice fresh. His two music publishing businesses take up a good deal of his time since he personally checks on all the songs that get past his brother John with a recommendation.

He Isn’t Greedy

“You can’t afford to overlook anything submitted in the music publishing business,” he told me. “Song writers are spurt people. They jot down the flash as it comes because if it’s not caught on the fly if often leaves never to return. ‘Clancy Lowered the Boom’ was submitted to me on the back of a laundry list, probably the only piece of paper at hand.” Dennis thinks he has another hit in “When I Was Young and Twenty,” from the Housman poem which he has set to music.

Eugene Dennis McNulty isn’t money greedy, but he knows the value of a dollar. And he has a certain inflexibility when it comes to things that might interfere with his standards—nobody can break him down. He is the only big-moneyed entertainer in Hollywood without a swimming pool. His home, which he bought before he married, and which is in a conservative residential section of Los Angeles, might be the home of a doctor or lawyer.

After Dennis Day had gone I remembered all the times I’d sat in my library listening to that golden voice. There, I thought to myself, goes talent and brains and manners and high ideals and charm—there goes a boy every woman in the world would be proud to call son.

Hedda Hopper was 65 years old when she wrote this column. Right in Dennis Day’s motherly musical audience demographic. When you sing sentimental songs from the Victrola days, you attract fans who are sentimental for the songs from the Victrola days. It would have been pointless, and far less lucrative, to hope for some other result. It may have been frustrating at times, but if fans wanted a naïve, boyish singer, that’s what Dennis Day gave them. It’s the reason why he’s remembered today.

There’s a bit of irony in that. Day owed his career to the fact that Kenny Baker wearied of the same stereotype that Day did, and quit the Jack Benny radio show because of it. Day stuck with it. It was the wisest career decision. Not only did his role expand a bit on the Benny show—he got to show off his ability to do impressions—he ended up getting his own starring show on NBC. But, again, he was playing a watered down version of his character on the Benny show, a naïve, somewhat silly young man who was a little awkward around young women.

There’s a bit of irony in that. Day owed his career to the fact that Kenny Baker wearied of the same stereotype that Day did, and quit the Jack Benny radio show because of it. Day stuck with it. It was the wisest career decision. Not only did his role expand a bit on the Benny show—he got to show off his ability to do impressions—he ended up getting his own starring show on NBC. But, again, he was playing a watered down version of his character on the Benny show, a naïve, somewhat silly young man who was a little awkward around young women.All this seems to have perturbed Dennis as he looked to expand his career past the narrow role people continued to want to see him in. He talked about it in the public press in 1950 as he pushed his new movie. Here’s one syndicated column.

In Hollywood

By ERSKINE JOHNSON

HOLLYWOOD, July 1 (NEA)—Maybe it won’t impress Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner, but Dennis Day, who has million-dollars tonsils, too, gets worry lines right under his widow’s peak whenever he thinks about Gloria de Haven.

The fancy forehead corrugation hasn’t a thing to do with bullfighters, either.

It seems that Gloria, a Hollywood doll who seldom gets a ting-a-ling when they’re looking for stained-glass window types, is about to throw a monkey wrench with SEX engraved on it smack into the middle of Dennis’ fan club of dear, old white-haired ladies.

When Gloria finishes hustling him soundly in Fox’s “I’ll Get By,” Dennis broods, the radio-confected pictures of him at an innocent lad in short pants will go boom-boom.

It’s worrying Dennis in the same way it would worry Gene Autry if he found himself in Mae West’s boudoir right in front of a million bubble-gum blowers.

Dennis looked around furtively and told me:

“I’m box office with those old girls. When I play theaters, they hobble down the aisles on crutches and smash into other people with their wheel chairs. Tired business men want to see Jane Russell. The white-haired gals who collect old-age pensions want to see me.”

Dennis says he’s been putting on the Little Lord Fauntleroy smile for years whenever somebody’s grandma yells for him.

He Knows, Girls

“They think I’m really the mother’s boy I play on Jack Benny’s radio show,” he sighed. “They don’t give me credit for knowing about the birds and bees.”

But there won't be any doubts when the picture is released, he’s sure.

“I get Gloria to make an honest man out of me by mentioning my mink farm. When Gloria hears me say ‘mink,’ she goes wild and screams, ‘Br-r-r-r-rother!’ Only the way Gloria bellows it, the word hasn’t got anything to do with National Brotherhood Week.”

Dennis can just see his picture turned to the wall in the parlors of the Day fans who look like Jack Benny in his Charley’s Aunt wig. He doesn’t think there’s a chance that it will be Gloria’s picture that gets the flip-over treatment. His over-sixty fans aren’t the kind who go around framing photos of girls in the Betty Grable league.

“I’ll Get By” is Dennis’ second movie—his No. 1 try was something called “Music in Manhattan” with Ann Shirley and Phil Terry about 10 years ago—and marks his first screen encounter with molten lipstick.

“Now,” he says, “I know how Shirley Temple felt when she got kissed for the first time.”

Dennis says that he’s been goggle-eyed about the radio public’s willingness to believe anything that comes bouncing over the air waves since he became the big load of whimsey on the Benny show in 1939. He complains:

“They think that Marie Wilson is a mental giant beside me. I have to go around saying, ‘I’m not a schmoe, I’m not a schmoe.’”

He’s lost count of the letters asking him about his wrestling, steam-fitting mother — “She’s really a demure lady”—and the age at which he was dropped on his noggin.

Even radio actors buttonhole him and whisper:

“Hey, just between you and me, is Jack Benny really that tight with a buck?”

Fair-Haired Boy

When Dennis isn’t peeking into Ulcerland about his first celluloid sex skirmish, he’s apt to go into a brown study about the Mother Macrees who haven’t seen him and think of him as a tall blond kid with hayseeds sticking out of his ears.

“Maybe,” says Dennis, “they’ll fall flat on their faces when they see me. Maybe the studio should have used the Larry Parks technique and hired Claude Jarman, Jr., or Butch Jenkins to play me.”

He says a lot of radio singers who have been trying to burst into movies for years fainted dead away and had to go to bed when word leaked out that he had turned down a chance to jump from “I’ll Get By” into RKO’s “Two Tickets to Broadway.”

One stopped him and said:

“Who are you to turn down pictures—Princess Aly Khan?”

Dennis has quite a reputation for his mimicry but nobody he imitates has ever threatened to give him a poke in the snoot. He’s not sure about Ronald Colman, though. When Colman first heard Dennis give out with the “I say, Bonita,” he turned to his wife and said:

“I say, Bonita, isn’t that a wonderful imitation of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.?”

Dennis hasn't figured it out yet.

“Maybe,” he says, “Colman doesn’t like Doug, Jr.”

“Princess Aly Khan” was better known as Rita Hayworth, who spent a fair chunk of time after her marriage refusing to work on pictures Columbia insisted on putting her in.

The following day, Hedda Hopper devoted her entire Sunday column to Dennis. You’ve got to love the way Hedda makes herself part of the story. And she gives a bit of insight into how canny Dennis was. There’s was a reason he inflicted “Clancy Lowered the Boom” on the Benny audience. He made money off it.

Dennis Day-He's Such a Boy

You'd never think that nostalgic tenor, that youthful innocence, that dumbjohn naivete came from a tough veteran in show business!

By HEDDA HOPPER

HOLLYWOOD—To millions of people Dennis Day is the eternal boy—a naive lad who says the things that most people only think, a lad who sings sweet songs in a tenor that calls forth nostalgic tears. And in recent years the public has come to think of Dennis as one of the world’s best comedians and imitators.

Every two years radio man Day shows his fans Dennis Day in the flesh through personal appearance tours across the nation.

And once in a blue moon Dennis makes a motion picture. This is his picture year. He’s co-starring in “I’ll Get By” at Twentieth Century-Fox with June Haver, Bill Lundigan and Gloria de Haven, and with such top stars as Clifton Webb, Jeanne Crain, Dan Dailey and Vic Mature doing specialty spots as background for his unique talents.

Won’t Sign Up

“You haven’t made a picture in six years,” I observed over our tea. “Why? It’s easier to let your public, see you on the screen than to go out on those killing personal appearance tours—and the money all goes out in tax anyway.”

“That’s true,’ said Dennis, “but you can’t find a producer who will let you off with one picture. They all want to sign you up for a baker’s dozen, and that I can’t do. Darryl Zanuck is the exception—when he wants you he’ll take you for a one-shot. He and Bill Perlberg don’t play that cards-to-the-chest game. They go out to make a top picture, and that's their first consideration.”

“Then you won’t make a p.a. tour this year?” I asked.

“No. I’ll spend my vacation time at Balboa,” he replied. “I’ve a house there and a little boat, and I’ll get 13 weeks rest. But I’ll go out on tour next year. The last time I went out we did six shows a day and I sing nine songs at each show. That’s work, sister. Toward the end of the tour I caught cold and lost my voice. I wanted to throw in the sponge, but you can’t let audiences down, so I came out and emceed the show in a croaking whisper until the voice got straightened out.”

His Name’s McNulty

Bronx-born Eugene Dennis McNulty is a fine looking lad in a drawing room. He wears with case and assurance clothes made by the best tailors. His ebony hair and heart-warming smile, a ready wit and flashes of temperamental fire make him a personality to remember. In private life the shy, star-struck boy of the radio becomes a man of modest reticence. He qualifies his success story repeatedly with use of the word “luck.”

“Luck has everything to do with it,” he said. “If Kenny Baker hadn’t pulled out of the Jack Benny show when he did, I’d probably be working away at the law. That’s what I wanted to be— a criminal lawyer. I find that branch absorbing.”

I wanted to know how a would-be criminal lawyer wound up as a world famous entertainer. “Didn’t that take some fancy footwork?” I asked.

“Oh, no. I’d always sung a bit. In the choir at St. Patrick’s cathedral when I was a small boy. I sang alto. Then when I was at Manhattan college we did some amateur shows with Larry Clinton’s orchestra. And I sang a couple of times on radio shows so in my spare time I’d fool about with recordings. I was recovering from an appendix operation when I made a recording of ‘Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair.’ Some fellows from a Canadian corporation were in the next room when I was cutting it and heard me. They bought it for $75. I ran home with the money and you can imagine the excitement. ‘A wonderful country this,’ my father said, ‘that pays you for singing. Why, when I sang in Ireland, they threw water at me!’”

It seems there were other singers among the McNultys. Dennis’ grandmother has a very fine voice and his mother is musical also.

“Mother played the tenement house piano—that’s what we call the accordion—at her own wedding,” Dennis explained. “She plays it now when we have a family get-together around the piano.”

So many McNultys came to California after Dennis arrived that they just bought they own apartment house and settled down. I wanted to know how many songs Dennis knew by heart.

Got to Keep Working.

He thought a moment. “It would run into the thousands I guess.” he smiled deprecatingly.

“You can’t help knowing a good many when you've been singing as long as I have. Then, you see, I take a singing lesson every day when I’m not making a picture. You can’t stand on your honors in life— you've got to keep working.”

Dennis sang a number of songs when he auditioned for the Jack Benny program—“I Never Knew Heaven Could Speak” and “Don’t Worry About Me” and “Yours Is My Heart Alone,” “A Pretty Girl Is Like A Melody,” “I’ll Follow My Secret Heart” and I don't know how many more. But it was “Jeanie” which caught Mary Livingstone’s fancy and which got him the chance to land in what he calls “the greatest showcase in the world”— the Benny show.

When Jack finally called Dennis’ name singling him out of a room full of hopeful aspirants, it was Dennis’ instant response “Yes, please,” which keyed the eternally fresh character he plays. He was nervous and reticent and his voice was higher than normal and a trifle breathless. Jack Benny a master showman, recognized his comedy value. “There’s our boy,” he told Mary. “We’ll play him just like that— a shy utterly sincere boy whose mother is somewhere in the offing all the time.”

Correct Psychology

Correct PsychologyJack’s psychology was correct. Mrs. Patrick McNulty, who was Mary Grady of Carracastle, Ireland, has reared a family of four sons and a daughter to be proud of. It was his mother who introduced Dennis to Peggy Almquist, his wife and the mother of small Paddy and Denny. One brother is a doctor, another a teacher of electrical engineering at U.C.L.A., another is Denny’s business manager, and the fourth is in the pharmaceutical business. Dennis’ sister is married and the mother of four, and Grandma McNulty has nine grandchildren to fuss over, and she’s not yet 60.

Dennis has one great difficulty! There aren’t enough hours in a day for him He says he’s an eight-hour man when it comes to sleep and just must have it to keep his voice fresh. His two music publishing businesses take up a good deal of his time since he personally checks on all the songs that get past his brother John with a recommendation.

He Isn’t Greedy

“You can’t afford to overlook anything submitted in the music publishing business,” he told me. “Song writers are spurt people. They jot down the flash as it comes because if it’s not caught on the fly if often leaves never to return. ‘Clancy Lowered the Boom’ was submitted to me on the back of a laundry list, probably the only piece of paper at hand.” Dennis thinks he has another hit in “When I Was Young and Twenty,” from the Housman poem which he has set to music.

Eugene Dennis McNulty isn’t money greedy, but he knows the value of a dollar. And he has a certain inflexibility when it comes to things that might interfere with his standards—nobody can break him down. He is the only big-moneyed entertainer in Hollywood without a swimming pool. His home, which he bought before he married, and which is in a conservative residential section of Los Angeles, might be the home of a doctor or lawyer.

After Dennis Day had gone I remembered all the times I’d sat in my library listening to that golden voice. There, I thought to myself, goes talent and brains and manners and high ideals and charm—there goes a boy every woman in the world would be proud to call son.

Hedda Hopper was 65 years old when she wrote this column. Right in Dennis Day’s motherly musical audience demographic. When you sing sentimental songs from the Victrola days, you attract fans who are sentimental for the songs from the Victrola days. It would have been pointless, and far less lucrative, to hope for some other result. It may have been frustrating at times, but if fans wanted a naïve, boyish singer, that’s what Dennis Day gave them. It’s the reason why he’s remembered today.

Labels:

Erskine Johnson

Saturday, 21 January 2012

No Money in Cartoons

Before the end of block booking in 1948, which stopped studios from forcing theatres to accept their short subjects along with features, cartoon producers were teetering on unprofitability. The war had stopped a lot of their overseas business for obvious reasons. Then came another financial blow in 1947, as related by this United Press story.

Bugs Bunny to be Rationed

England’s Embargo Hits Home At Cartoon Factories

By VIRGINIA MacPHERSON

HOLLYWOOD, Oct. 16—(U.P.)—The British tax became something real to movie-goers today when they discovered they’re going to be rationed on Woody Woodpecker and Bugs Bunny.

Yep—fewer cartoons.

Up to now England’s embargo on Hollywood has been something the fans would just as soon let producers worry about. But it’s beginning to hit home.

Of the eight cartoon factories, two have shut down altogether. Columbia Studios, which makes “The Fox and the Crow,” took a look at their profits, discovered there weren’t any, and went out of business.

George Pal, whose bug-eyed “Jasper” kept kids happy at Saturday matinees, has chopped off his Puppetoons. He's going in for full-length features, where he can make some money.

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” shrugged Walter Lantz, president of the Cartoon Producers’ Association. “We’re not going to get our dough back from the domestic market. Europe used to help us make a profit. Now everybody’s losing money.”

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” shrugged Walter Lantz, president of the Cartoon Producers’ Association. “We’re not going to get our dough back from the domestic market. Europe used to help us make a profit. Now everybody’s losing money.”

So Lantz, who makes “Woody Woodpecker” and “Andy Panda,” is cutting down. In 1942 he had 13 cartoons out by August. This year he has eight. It’s the same all over town. M.G.M.’s “Tom and Jerry” are coming out 10 times this year. Five years ago they were in 16 cartoons. Paramount’s “Popeye” gulps spinach 15 times, as compared to 25 in 1942.

Even Disney’s slowing up. “Mickey Mouse” and company hit your movie house only every six weeks now. They used to be there once a month.

“Bugs Bunny” and Warners’ “Merry Melodies” are really taking it easy. They’ve slowed from a fast 42 a year to 16.

“And if the other companies are anything like mine, they’re losing money on every one,” Lantz said. “My costs have gone up 165 per cent since 1940. Profits? A measly 12 per cent. We spend $25,000 for a six-minute short now—and wait 18 months to get it back.”

Trouble is, he said, theater managers want a cartoon for $2.50 a week. They get it, too.

“Feature pictures get a percentage,” Lantz explained. “But cartoons come for a flat rate. Awful flat I might add. Exhibitors still think they’re fillers—something to fill up the screen with while the customers go out for more popcorn.”

At least, the British tax hasn’t cut down on that—yet.

Wood Soanes of the Oakland Tribune sniffed his response in the entertainment pages on October 23:

Soanes seems to be under the impression that if the cartoons were “better,” producers would get more money for them. But he doesn’t address the fact that the movie-going public felt they got more for their money with two features instead of one feature and several short subjects they didn’t have a great deal of interest in.

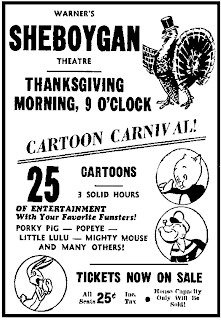

While cartoons directors would say decades later “Cartoons weren’t made for children,” that certainly appears to have been the primary audience attracted to them even before 1947. Theatre owners knew it. They scheduled whole afternoons of nothing but cartoons aimed at a kid audience, packaging shorts from several different producers together, often under the “cartoon carnival” moniker.

While cartoons directors would say decades later “Cartoons weren’t made for children,” that certainly appears to have been the primary audience attracted to them even before 1947. Theatre owners knew it. They scheduled whole afternoons of nothing but cartoons aimed at a kid audience, packaging shorts from several different producers together, often under the “cartoon carnival” moniker.

Studios never wised up to the value of their cartoons. All they saw is how long it took for them to bring in money. When television became the home entertainment medium of choice in the ‘50s, the studios eagerly sold their cartoons to distributors in that business, who proceeded to make a killing re-selling packages of them to television stations desperate for tried-and-true kid content. So studios never wised up to the true value of television, at least initially, but their short-sightedness allowed countless kids to fall in love with the classic cartoons and ensure their preservation even to today.

Bugs Bunny to be Rationed

England’s Embargo Hits Home At Cartoon Factories

By VIRGINIA MacPHERSON

HOLLYWOOD, Oct. 16—(U.P.)—The British tax became something real to movie-goers today when they discovered they’re going to be rationed on Woody Woodpecker and Bugs Bunny.

Yep—fewer cartoons.

Up to now England’s embargo on Hollywood has been something the fans would just as soon let producers worry about. But it’s beginning to hit home.

Of the eight cartoon factories, two have shut down altogether. Columbia Studios, which makes “The Fox and the Crow,” took a look at their profits, discovered there weren’t any, and went out of business.

George Pal, whose bug-eyed “Jasper” kept kids happy at Saturday matinees, has chopped off his Puppetoons. He's going in for full-length features, where he can make some money.

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” shrugged Walter Lantz, president of the Cartoon Producers’ Association. “We’re not going to get our dough back from the domestic market. Europe used to help us make a profit. Now everybody’s losing money.”

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” shrugged Walter Lantz, president of the Cartoon Producers’ Association. “We’re not going to get our dough back from the domestic market. Europe used to help us make a profit. Now everybody’s losing money.”So Lantz, who makes “Woody Woodpecker” and “Andy Panda,” is cutting down. In 1942 he had 13 cartoons out by August. This year he has eight. It’s the same all over town. M.G.M.’s “Tom and Jerry” are coming out 10 times this year. Five years ago they were in 16 cartoons. Paramount’s “Popeye” gulps spinach 15 times, as compared to 25 in 1942.

Even Disney’s slowing up. “Mickey Mouse” and company hit your movie house only every six weeks now. They used to be there once a month.

“Bugs Bunny” and Warners’ “Merry Melodies” are really taking it easy. They’ve slowed from a fast 42 a year to 16.

“And if the other companies are anything like mine, they’re losing money on every one,” Lantz said. “My costs have gone up 165 per cent since 1940. Profits? A measly 12 per cent. We spend $25,000 for a six-minute short now—and wait 18 months to get it back.”

Trouble is, he said, theater managers want a cartoon for $2.50 a week. They get it, too.

“Feature pictures get a percentage,” Lantz explained. “But cartoons come for a flat rate. Awful flat I might add. Exhibitors still think they’re fillers—something to fill up the screen with while the customers go out for more popcorn.”

At least, the British tax hasn’t cut down on that—yet.

Wood Soanes of the Oakland Tribune sniffed his response in the entertainment pages on October 23:

Well, I have no doubt that the British embargo is having its effect, but it isn’t the basic cause. Several months before Britain decided on its new tax arrangements, the cartoon producers were in the public print screaming that they couldn’t go on unless they got better terms.

The cartoon men claim they are being given the brush-off by the feature producers; the exhibitors claim that with the public demanding double bills there is no time for cartoons. In short, everyone is blaming everybody else. The sorry fact is that most of the cartoons aren’t worth the powder to blow them to Never-never land.

Soanes seems to be under the impression that if the cartoons were “better,” producers would get more money for them. But he doesn’t address the fact that the movie-going public felt they got more for their money with two features instead of one feature and several short subjects they didn’t have a great deal of interest in.

While cartoons directors would say decades later “Cartoons weren’t made for children,” that certainly appears to have been the primary audience attracted to them even before 1947. Theatre owners knew it. They scheduled whole afternoons of nothing but cartoons aimed at a kid audience, packaging shorts from several different producers together, often under the “cartoon carnival” moniker.

While cartoons directors would say decades later “Cartoons weren’t made for children,” that certainly appears to have been the primary audience attracted to them even before 1947. Theatre owners knew it. They scheduled whole afternoons of nothing but cartoons aimed at a kid audience, packaging shorts from several different producers together, often under the “cartoon carnival” moniker.Studios never wised up to the value of their cartoons. All they saw is how long it took for them to bring in money. When television became the home entertainment medium of choice in the ‘50s, the studios eagerly sold their cartoons to distributors in that business, who proceeded to make a killing re-selling packages of them to television stations desperate for tried-and-true kid content. So studios never wised up to the true value of television, at least initially, but their short-sightedness allowed countless kids to fall in love with the classic cartoons and ensure their preservation even to today.

Friday, 20 January 2012

Arch in the Latin Quarter

If you’re going to set a cartoon in Paris, you’d better have an appropriate opening. And that’s what you get in Bob McKimson’s “French Rarebit” (1951). Gene Poddany plays ‘Latin Quarter’ over the opening titles and then Milt Franklyn changes the arrangement for the start of the cartoon, which features a fairly literal drawing of the Arc du Triomphe.

Layout man Cornett Wood has the arch set at an angle. The background was painted by Dick Thomas.

Animator Mark Kausler informs me Wood had a storefront under the Hollywood Freeway on Cahuenga Blvd. where he taught drawing into the late ‘60s. Indiana’s Laughmakers, The Story of over 400 Hoosiers by Ray Banta reveals the following:

Cornett Wood went on from John Herron Art School of Indianapolis to become one of the animators for the fabulous Walt Disney production, Fantasia. The feature released in 1940 was called “a tribute to the brilliance of Walt Disney’s staff of artists and animators.” It involved a series of visualizations of musical themes. Wood worked as an effects animator at Disney from March 7, 1938 to September 12, 1941.

After which, he found himself at the Schlesinger studio.

Wood was born September 12, 1905 and died in Los Angeles on May 16, 1980.

Incidentally, if you want to learn more about the Latin Quarter (the area in Paris, not the song by Warren and Dubin), drop by this web site.

Layout man Cornett Wood has the arch set at an angle. The background was painted by Dick Thomas.

Animator Mark Kausler informs me Wood had a storefront under the Hollywood Freeway on Cahuenga Blvd. where he taught drawing into the late ‘60s. Indiana’s Laughmakers, The Story of over 400 Hoosiers by Ray Banta reveals the following:

Cornett Wood went on from John Herron Art School of Indianapolis to become one of the animators for the fabulous Walt Disney production, Fantasia. The feature released in 1940 was called “a tribute to the brilliance of Walt Disney’s staff of artists and animators.” It involved a series of visualizations of musical themes. Wood worked as an effects animator at Disney from March 7, 1938 to September 12, 1941.

After which, he found himself at the Schlesinger studio.

Wood was born September 12, 1905 and died in Los Angeles on May 16, 1980.

Incidentally, if you want to learn more about the Latin Quarter (the area in Paris, not the song by Warren and Dubin), drop by this web site.

Labels:

Bob McKimson,

Dick Thomas

Thursday, 19 January 2012

Takes From Northwest Hounded Police

“Northwest Hounded Police” (1946) has the takes that Tex Avery became famous for. The last one has the veins growing in Wolfie’s eyes.

The animators on this cartoon were Ed Love, Preston Blair, Ray Abrams and Walt Clinton. Frank Graham supplies Wolfie’s voice. Bill Thompson must still have been on military service because he’s not doing Droopy in this one.

The animators on this cartoon were Ed Love, Preston Blair, Ray Abrams and Walt Clinton. Frank Graham supplies Wolfie’s voice. Bill Thompson must still have been on military service because he’s not doing Droopy in this one.

Wednesday, 18 January 2012

Jack Benny on the Air, 1929

A few days ago, we espoused the opinion on this blog that Jack Benny’s first appearance on the radio wasn’t in 1932, as he had claimed for many years, and pointed out a 1931 appearance on the ‘RKO Theater of the Air’ as likely being the first. A search found no evidence of any broadcasts in 1930 (though Tim Lones of the Cleveland Classic Media blog found one) and the grind of vaudeville would almost preclude anything in the ‘20s.

Turns out we were half right.

Laura Leff of the International Jack Benny Fan Club may know about Jack Benny than anyone alive, save Jack’s daughter Joan. She sent a note that she was sure Jack had done some radio in the late ‘20s in Los Angeles when he was under contract to M-G-M. So back to the digging we went. And, as usual, it turns out Laura was correct. Jack’s famous Ed Sullivan show of 1932 wasn’t his first radio appearance. But it wasn’t in 1931, either.

To the right, you see a clipping from the radio page of the Oakland Tribune of October 9, 1929. At the very bottom, it reads:

To the right, you see a clipping from the radio page of the Oakland Tribune of October 9, 1929. At the very bottom, it reads:

“Tonight KFRC will have Jack Benny as master of ceremonies for the Mavio [sic] club from 8 to 9. Marie Wells, popular musical comedienne, will sing a group of songs.”

A check of listings in the Tribune and other California papers (unfortunately, I don’t have access to any Los Angeles papers of the day) clears up the mystery. The show was called ‘The MGM Movie Club’ and it originated from KHJ, the Don Lee network station in Los Angeles. Don Lee owned KFRC in San Francisco and had four affiliates up the West Coast. On August 10, 1929, United Press reported Don Lee was merging his six stations with CBS as of the following January 1st. ‘The M-G-M Movie Club’ was a regularly scheduled show; the previous week featured Basil Rathbone hosting, with Cliff Edwards, Bob Montgomery and forgotten stars Ethelind Terry, Lawrence Gray, the Three Twins and Catherine Dale Owens.

I don’t know any more about the programme or the broadcast itself, though Marie Wells’ presence is puzzling as she was under contract to Warner Bros.

At the time, Jack was about to open in M-G-M’s ‘The Hollywood Revue’ with just about every star the studio had at the time. No doubt that’s what he was pushing on the broadcast. So I won’t go so far as to say October 9, 1929 was Jack Benny’s first appearance on the radio. But we do know it wasn’t 1932 as legend would have you believe.

At the time, Jack was about to open in M-G-M’s ‘The Hollywood Revue’ with just about every star the studio had at the time. No doubt that’s what he was pushing on the broadcast. So I won’t go so far as to say October 9, 1929 was Jack Benny’s first appearance on the radio. But we do know it wasn’t 1932 as legend would have you believe.

This post gives me a chance to talk about Laura Leff’s Labour of Love. Laura has just published Volume 3 of “39 Forever.” The first two volumes feature detailed research on every single episode of Jack Benny’s radio programme, including casts, sketches, “firsts”, songs, appearances of the “Anaheim, Azusa and Cucamonga” gag, screw-ups. Anyone who loves Jack’s radio show should have them. Laura’s now devoted a third volume to Jack’s television series. Almost anything you wanted to know about the show is there. You can read more about it HERE and if you want to find out what else the Fan Club offers, stop by HERE.

By the way, ‘The Hollywood Revue’ of 1929 is memorable in that it brought us that wonderful song “Singin’ in the Rain” long before Gene Kelly’s immortal dance to it in the movie of the same name. You can see briefly Jack at the end of this clip (next to Marie Dressler and a teeny umbrella) along with one of Hollywood’s greatest ever comic actors, Buster Keaton. And you may recognise a few other soggy faces.

Turns out we were half right.

Laura Leff of the International Jack Benny Fan Club may know about Jack Benny than anyone alive, save Jack’s daughter Joan. She sent a note that she was sure Jack had done some radio in the late ‘20s in Los Angeles when he was under contract to M-G-M. So back to the digging we went. And, as usual, it turns out Laura was correct. Jack’s famous Ed Sullivan show of 1932 wasn’t his first radio appearance. But it wasn’t in 1931, either.

To the right, you see a clipping from the radio page of the Oakland Tribune of October 9, 1929. At the very bottom, it reads:

To the right, you see a clipping from the radio page of the Oakland Tribune of October 9, 1929. At the very bottom, it reads:“Tonight KFRC will have Jack Benny as master of ceremonies for the Mavio [sic] club from 8 to 9. Marie Wells, popular musical comedienne, will sing a group of songs.”

A check of listings in the Tribune and other California papers (unfortunately, I don’t have access to any Los Angeles papers of the day) clears up the mystery. The show was called ‘The MGM Movie Club’ and it originated from KHJ, the Don Lee network station in Los Angeles. Don Lee owned KFRC in San Francisco and had four affiliates up the West Coast. On August 10, 1929, United Press reported Don Lee was merging his six stations with CBS as of the following January 1st. ‘The M-G-M Movie Club’ was a regularly scheduled show; the previous week featured Basil Rathbone hosting, with Cliff Edwards, Bob Montgomery and forgotten stars Ethelind Terry, Lawrence Gray, the Three Twins and Catherine Dale Owens.

I don’t know any more about the programme or the broadcast itself, though Marie Wells’ presence is puzzling as she was under contract to Warner Bros.

At the time, Jack was about to open in M-G-M’s ‘The Hollywood Revue’ with just about every star the studio had at the time. No doubt that’s what he was pushing on the broadcast. So I won’t go so far as to say October 9, 1929 was Jack Benny’s first appearance on the radio. But we do know it wasn’t 1932 as legend would have you believe.

At the time, Jack was about to open in M-G-M’s ‘The Hollywood Revue’ with just about every star the studio had at the time. No doubt that’s what he was pushing on the broadcast. So I won’t go so far as to say October 9, 1929 was Jack Benny’s first appearance on the radio. But we do know it wasn’t 1932 as legend would have you believe.This post gives me a chance to talk about Laura Leff’s Labour of Love. Laura has just published Volume 3 of “39 Forever.” The first two volumes feature detailed research on every single episode of Jack Benny’s radio programme, including casts, sketches, “firsts”, songs, appearances of the “Anaheim, Azusa and Cucamonga” gag, screw-ups. Anyone who loves Jack’s radio show should have them. Laura’s now devoted a third volume to Jack’s television series. Almost anything you wanted to know about the show is there. You can read more about it HERE and if you want to find out what else the Fan Club offers, stop by HERE.

By the way, ‘The Hollywood Revue’ of 1929 is memorable in that it brought us that wonderful song “Singin’ in the Rain” long before Gene Kelly’s immortal dance to it in the movie of the same name. You can see briefly Jack at the end of this clip (next to Marie Dressler and a teeny umbrella) along with one of Hollywood’s greatest ever comic actors, Buster Keaton. And you may recognise a few other soggy faces.

Labels:

Jack Benny

I Don’t Wanna Buy One

Some comedians are an acquired taste. I never acquired one for Joe Penner. And seeing he’s been dead for 70 years, I likely won’t acquire one. But I sure like this ad for his film debut, ‘College Rhythm’ (1934). We get a realistic Penner and a cartoon duck. Duck as in “Wanna buy a.”

Some comedians are an acquired taste. I never acquired one for Joe Penner. And seeing he’s been dead for 70 years, I likely won’t acquire one. But I sure like this ad for his film debut, ‘College Rhythm’ (1934). We get a realistic Penner and a cartoon duck. Duck as in “Wanna buy a.”

Cartoons are about the only place anyone knows Penner from these days. Danny Webb borrowed his voice for Egghead at Warner Bros. (notably in ‘Daffy Duck and Egghead’). And the annoying rabbit characters in the Warners’ animated short ‘My Green Fedora’ (1935) were Penner-ised with one dressing like him and the other laughing like him. Penner was a huge, but fleeting, radio star. Rudy Vallee “discovered” him in 1933 and played straight man to him. This clip is courtesy of Craig Hodgkins’ very good site on Penner.

Radio isn’t kind to people whose routine consists of little more than a couple of catchphrases. And that’s about all Penner had, besides a childishly-whiny voice. Penner realised a little too late that you could go on with the same act for years in vaudeville, but not on radio. In 1936, he gave up his duck and tried a new radio show written by Harry W. Conn, the man who thought he made Jack Benny, but his career had peaked.

Penner continued in movies, walking from RKO to Universal in a salary dispute in 1939, before his sudden death on January 10, 1941. He was 36. The catchphrases he tried to give up followed him to the grave; some front page newspaper stories showed a publicity shot of Penner and his duck. Click on them below to see the clippings in larger form.

Philadelphia, Jan. 11 (AP)—Millions who had howled hilarious approval of a little Hungarian comedian and his incessant “Wanna Buy a Duck?” were touched by sadness today with the death of Joe Penner.

The 36-year-old funnyman who brought the nation many a laugh through the screen, stage and radio, died in his sleep yesterday. Pending an autopsy, the cause was given as a heart attack.

The 36-year-old funnyman who brought the nation many a laugh through the screen, stage and radio, died in his sleep yesterday. Pending an autopsy, the cause was given as a heart attack.Penner, seeking a rest, had asked not to be disturbed in his hotel room — Mrs. Penner told how hard he had been working on his new show “Yokel Boy,” which opened here Monday — and was found dead in bed about 5 P. M., by his wife.

Only the night before, friends said Penner — born Josef Pinter in a tiny Hungarian village — had appeared in his gayest mood. After the show, he escorted Mrs. Penner and comedienne Martha Raye, their guest, to a night club.

Robert Crawford, his co-producer and general manager, said the star called upon, returning to the hotel and seemed “in the best of spirits.” Mrs. Penner, the former Mae Vogt, a dancer in Joe’s first show, was placed under a physician’s care.

There was no understudy for the star of “Yokel Boy” and the Locust Street Theater was dark last night. Crawford has not decided whether it will be continued.

Penner was brought to this country at the age of nine by his grandparents, and joined his parents in Detroit, where the father worked in a motor car factory. School and odd jobs had no appeal for a youngster who showed more aptitude for clowning than classes, but a prize for an amateur impersonation of Charlie Chaplin started him on his way to stardom.

His first theatrical job was assistant to a mind reader—until the comedian on the bill failed to show up. Penner stepped in, and there followed several seasons of vaudeville, carnivals, burlesques and nightclubs. The first big break came in 1926, a role at $375 a week in the “Greenwich Village Follies.” In 1933 Rudy Vallee had Penner as guest star on radio, and a few weeks later he was featured on his own program.

The death of Joe Penner may cancell [sic] the road tour of “Yokel Boy,” the Lew Brown-Ray Henderson musical in which the comedian was making a stage “comeback.” The show had been booked for a one-night engagement on Jan. 29 at the Empire, but no news of cancellation has been received by Harry Unterfoot, city manager of RKO-Schine theaters, who is supervising the theater.

Tuesday, 17 January 2012

A Camel in Morocco

Camels are funny-looking things, especially in cartoons. Probably the funniest-looking camel in a cartoon not made by Warner Bros. is in the Walter Lantz cartoon ‘Socko in Morocco’ (released in January 1954). It’s one of the shorts Don Patterson handled during his far-too-short tenure as a director.

For reasons known only to Patterson, and perhaps writer Homer Brightman, the camel is partly hollow. Buzz Buzzard rides inside it.

Thad Komorowski tells me that Walter Lantz was so cheap, the directors at his studio had to their own design characters, unlike MGM where they had people like Claude Smith or Ed Benedict to do that sort of thing.

The camel is animated in silhouette and long shot at the beginning of his scene with a flurry of feet on ones. Then we get some medium shots. The animation is by Ken Southworth, Herman Cohen and Ray Abrams. Art Landy is credited with the very nice backgrounds; good design and sunset hues.

This cartoon has dialogue at the beginning and end, and virtually nothing in between. What few words on the soundtrack are handled by Dal McKennon as Buzz and a horse, while Grace Stafford is Woody and giggles for the princess. I’m presuming McKennon is also the French Foreign Legion commander, though he reminds me a lot more of Harry Lang than anyone else. Lang died about five months before this cartoon was released after suffering a lengthy illness.

This cartoon has dialogue at the beginning and end, and virtually nothing in between. What few words on the soundtrack are handled by Dal McKennon as Buzz and a horse, while Grace Stafford is Woody and giggles for the princess. I’m presuming McKennon is also the French Foreign Legion commander, though he reminds me a lot more of Harry Lang than anyone else. Lang died about five months before this cartoon was released after suffering a lengthy illness.

For reasons known only to Patterson, and perhaps writer Homer Brightman, the camel is partly hollow. Buzz Buzzard rides inside it.

Thad Komorowski tells me that Walter Lantz was so cheap, the directors at his studio had to their own design characters, unlike MGM where they had people like Claude Smith or Ed Benedict to do that sort of thing.

The camel is animated in silhouette and long shot at the beginning of his scene with a flurry of feet on ones. Then we get some medium shots. The animation is by Ken Southworth, Herman Cohen and Ray Abrams. Art Landy is credited with the very nice backgrounds; good design and sunset hues.

This cartoon has dialogue at the beginning and end, and virtually nothing in between. What few words on the soundtrack are handled by Dal McKennon as Buzz and a horse, while Grace Stafford is Woody and giggles for the princess. I’m presuming McKennon is also the French Foreign Legion commander, though he reminds me a lot more of Harry Lang than anyone else. Lang died about five months before this cartoon was released after suffering a lengthy illness.

This cartoon has dialogue at the beginning and end, and virtually nothing in between. What few words on the soundtrack are handled by Dal McKennon as Buzz and a horse, while Grace Stafford is Woody and giggles for the princess. I’m presuming McKennon is also the French Foreign Legion commander, though he reminds me a lot more of Harry Lang than anyone else. Lang died about five months before this cartoon was released after suffering a lengthy illness.

Labels:

Don Patterson,

Walter Lantz

Monday, 16 January 2012

Stage Door Clampett

Here’s an inside joke from Friz Freleng’s “Stage Door Cartoon.” Well, maybe it’s a sly editorial comment by someone in Freleng’s unit about the animators in Bob Clampett’s unit, because you can see a reference to Clampett in one of the background drawings.

Paul Julian liked referring to fellow Warners employees in his backgrounds. Julian didn’t get credit on this cartoon but it’s obviously his work. I love the little light reflection highlights he draws. Here are a couple of other backgrounds of his from early in the cartoon. They’re from layouts by an uncredited Hawley Pratt.

Jack Bradbury gets the sole animation credit, though the nice little Bugs tap dance is either by Virgil Ross or Gerry Chiniquy, depending on which animation ID expert one wishes to accept. Mike Maltese wrote the story, though several years later, Tedd Pierce put Bugs back on stage (this time, with Yosemite Sam instead of Elmer Fudd) and reworked the high-diving scene into a full cartoon, “High Diving Hare.”

Jack Bradbury gets the sole animation credit, though the nice little Bugs tap dance is either by Virgil Ross or Gerry Chiniquy, depending on which animation ID expert one wishes to accept. Mike Maltese wrote the story, though several years later, Tedd Pierce put Bugs back on stage (this time, with Yosemite Sam instead of Elmer Fudd) and reworked the high-diving scene into a full cartoon, “High Diving Hare.”

The cartoon was released just before Christmas 1944, according to one newspaper ad I’ve found, and was still playing at theatres into 1946.

Paul Julian liked referring to fellow Warners employees in his backgrounds. Julian didn’t get credit on this cartoon but it’s obviously his work. I love the little light reflection highlights he draws. Here are a couple of other backgrounds of his from early in the cartoon. They’re from layouts by an uncredited Hawley Pratt.

Jack Bradbury gets the sole animation credit, though the nice little Bugs tap dance is either by Virgil Ross or Gerry Chiniquy, depending on which animation ID expert one wishes to accept. Mike Maltese wrote the story, though several years later, Tedd Pierce put Bugs back on stage (this time, with Yosemite Sam instead of Elmer Fudd) and reworked the high-diving scene into a full cartoon, “High Diving Hare.”

Jack Bradbury gets the sole animation credit, though the nice little Bugs tap dance is either by Virgil Ross or Gerry Chiniquy, depending on which animation ID expert one wishes to accept. Mike Maltese wrote the story, though several years later, Tedd Pierce put Bugs back on stage (this time, with Yosemite Sam instead of Elmer Fudd) and reworked the high-diving scene into a full cartoon, “High Diving Hare.”The cartoon was released just before Christmas 1944, according to one newspaper ad I’ve found, and was still playing at theatres into 1946.

Sunday, 15 January 2012

Jack Benny on the Air, 1931

Fans of Old Time Radio have heard the story over and over, how Jack Benny first appeared on radio with Ed Sullivan in 1932, and what his first words were.

That isn’t how it happened.

Jack told the story over and over so much, he may have come to believe that’s how it happened. Sullivan told it, too. But Jack’s radio debut was not on Sullivan’s show and was not in 1932. Jack must have known it at one time because he celebrated his tenth year in radio on a special broadcast in 1941. Simple arithmetic dictates that his debut would have been in 1931. And that’s indeed when it was. September 4th to be exact.

To your right you see a newspaper column from the Capitol Times of Madison, Wisconsin of September 3, 1931, listing the following day’s radio programmes. There you can see Jack as a guest on ‘RKO Theater of the Air.’ The New York Times of September 4 shows the programme airing at 10:30 p.m. over WEAF, flagship of the Red Network of NBC. Also appearing in the hour-long show were Irish tenor Joseph Regan, and Aunt Jemima of “Show Boat.”

To your right you see a newspaper column from the Capitol Times of Madison, Wisconsin of September 3, 1931, listing the following day’s radio programmes. There you can see Jack as a guest on ‘RKO Theater of the Air.’ The New York Times of September 4 shows the programme airing at 10:30 p.m. over WEAF, flagship of the Red Network of NBC. Also appearing in the hour-long show were Irish tenor Joseph Regan, and Aunt Jemima of “Show Boat.”

If you’re wondering about the famous Sullivan show, the radio listings of Times for Tuesday, March 29, 1932 show:

That isn’t how it happened.

Jack told the story over and over so much, he may have come to believe that’s how it happened. Sullivan told it, too. But Jack’s radio debut was not on Sullivan’s show and was not in 1932. Jack must have known it at one time because he celebrated his tenth year in radio on a special broadcast in 1941. Simple arithmetic dictates that his debut would have been in 1931. And that’s indeed when it was. September 4th to be exact.

To your right you see a newspaper column from the Capitol Times of Madison, Wisconsin of September 3, 1931, listing the following day’s radio programmes. There you can see Jack as a guest on ‘RKO Theater of the Air.’ The New York Times of September 4 shows the programme airing at 10:30 p.m. over WEAF, flagship of the Red Network of NBC. Also appearing in the hour-long show were Irish tenor Joseph Regan, and Aunt Jemima of “Show Boat.”

To your right you see a newspaper column from the Capitol Times of Madison, Wisconsin of September 3, 1931, listing the following day’s radio programmes. There you can see Jack as a guest on ‘RKO Theater of the Air.’ The New York Times of September 4 shows the programme airing at 10:30 p.m. over WEAF, flagship of the Red Network of NBC. Also appearing in the hour-long show were Irish tenor Joseph Regan, and Aunt Jemima of “Show Boat.” If you’re wondering about the famous Sullivan show, the radio listings of Times for Tuesday, March 29, 1932 show:

WABC 860 Kcs.Jack always credited the Sullivan broadcast with raising interest with the folks at Canada Dry who then signed him for his own show. Jack seems to have misremembered this as a result of his first radio broadcast which, as you can see, was not the case at all. And, to be honest, having Ed Sullivan “discover” him made for a better story. Through all the years Jack told about his “first” broadcast, everyone knew who Sullivan was. Likely no one had heard of ‘RKO Theater of the Air.’ But now you have. And now you know when Jack Benny really began his illustrious and lengthy broadcast comedy career.

8:45 p.m.—Ed Sullivan Comments; Berger's Orch.; Jack Benny, Monologues.

Labels:

Jack Benny

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)