Daily Variety

Daily Variety told readers on January 16, 1942 about a cartoon. “Fred Avery will supervise production of ‘Blitz Wolf,’ cartoon subject at Metro.”

Avery had arrived at MGM the previous September and busied himself with

The Early Bird Dood It. This was the first cartoon Avery and his unit—Irv Spence, Ray Abrams, Preston Blair and Ed Love, likely assisted by effects animator Al Grandmain—worked on, with

The Blitz Wolf following. It seems odd that Avery would be employed on only one short for the first four months he was at Metro, but that’s what the trades at the time indicate.

Even odder is a blurb in

Daily Variety of June 17, 1942 saying Rich Hogan has bought himself out of his contract with Leon Schlesinger and “his first assignment being ‘Blitz Wolf.’” Why would he be writing a cartoon that had been started six months earlier? Especially one the

Hollywood Reporter said on June 2nd was “in last stages of work.”? And when the MGM newsletter of January-February 1942 revealed he was already at the studio.

(Hogan was loyal to Avery. He returned to Avery’s unit after WW2 military service and quit animation when Avery took time off to get his life together).

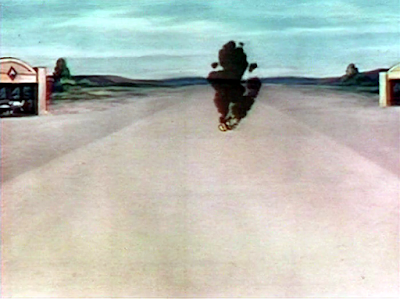

Avery and Hogan brought with them from Warner Bros. sign gags, fairy tale send-ups, characters talking to the audience, radio show references and Sara Berner’s voice talent. With ex-Disney animators under him, he could try for animation that was a little more elaborate at times than what he put on the screen when working for Leon Schlesinger. There are a couple of scenes of perfect perspective animation with something large in the foreground flying into the background.

Oh, there were unmatched shots, too. Here are two consecutive frames. Sergeant Pork, the Practical Pig, drums his fingers and begins to point. But his finger doesn’t get there.

The GI-garbed pig urges the other two to buy bonds and be prepared for the Big Bad Wolf. Here are some poses. The pig’s gestures are not way-over-the-top like in a Clampett cartoon. They seem perfectly natural. This is the work of the great Preston Blair. Sgt. Pork’s voice is courtesy of Pinto Colvig. He had finished his work in Florida on

Gulliver’s Travels and was back in Hollywood freelancing.

You can find more frames from the cartoon

by searching here. There’s a profile of Mr. Hogan as well.

The

Hollywood Reporter quoted Fred Quimby as stating on August 18th the cartoon was “winding up production.” If so, it wound up very fast. The press got a sneak preview the next night at the Filmarte Theatre by the Motion Picture Academy. It was the last short to be screened, and the programme included Superman’s

Terror of the Midway, the very good Norm McCabe war short

The Duck-Tators, Goofy in

The Olympic Champ and the Fox and Crow in

Woodman, Spare That Tree. About all

Daily Variety said about it was “solid laughs.” The

Reporter pronounced it “an especially ingenious release.”

The 887-foot film hit theatres on August 22nd, a week before

Early Bird. In

Weekly Variety’s edition of September 2nd, it concluded “With such a childish topic, Director Tex Avery and his crew have concocted a refreshing, laugh cartoon. Strong on any program.” (It also praised Avery in its review of

Early Bird in the same issue).

Boxoffice, on September 5th, was more lavish in its praise: “They don’t come any better...Audiences, recovering from their laughter, will stand up and cheer this one. Tex Avery, who directed, is a man to watch.” (It, too, thought

Early Bird was a “Top notcher...Tie the roof down when this one hits the projection machine”). From

Motion Picture Daily of September 2nd: “Top honors for ingenuity, comedy and brilliant satirical handling go to M-G-M for this color short...Directed by Tex Avery, this short is an added attraction on any bill” (It also mentioned Tex in its review of

Early Bird: “clever and amusing, and not above poking fun at the company that made it”).

Motion Picture Herald, misguided about who was responsible, wrote on August 29th: “is Fred Quimby, executive producer, at his best in the field of cartoon, and a subject which had the audience screaming.” And

Showman’s Trade Review included frames in its little story on the cartoon in the September 5th edition, calling it in a critique “novel, amusing and entertaining...Entire subject is excellently animated and contains much to humorously impress the need of precaution and preparedness.” It also notes that Hitler is blown to a Hell where he is greeted by Jews.

The Filmarte again screened the cartoon on February 3, 1943 as the Academy narrowed down its list of nominees for animated cartoon. Also on the list:

All Out For V (Terrytoons),

Juke Box Jamboree (Walter Lantz),

Tulips Will Grow (George Pal),

Pigs in a Polka (Schlesinger/Warner Bros.),

Der Fuehrer’s Face (Walt Disney). Alas, it lost to Disney with his elaborate dream sequence. However, in May, it did top a

Motion Picture Herald poll of exhibitors as the best industry-produced war cartoons (and was second on the list of shorts).

And Canada loved the cartoon, too. The

Hollywood Reporter revealed on April 1, 1943 “For its Fourth Victory Loan Drive, starting April 15, the Canadian government will distribute MGM’s cartoon, ‘The Blitz Wolf,’ which was also used as a war bond sales stimulant in this country. W.H. Burnside, director of production for the National Film Board of Canada, is here [in Los Angeles] making arrangements for 195 (16mm.) and 65 (35mm.) prints. The negative was furnished gratis by MGM.” This didn’t mean theatres. The cartoon was shown with other NFB propaganda films on a screen at Eaton’s in downtown Toronto every hour, seven times a day, in April 1944. In Vancouver and Victoria, “bond” shells were set up downtown where the cartoon played for anyone passing by.

Then

The Blitz Wolf disappeared, to return some time later with the bombing of Tokyo excised and a now-unflattering reference to the Japanese rubbed out. Hitler, of course, was still hated so he remained a rightful target of satire on both the big and little screen.

As for the story of how producer Quimby told Tex to take it easy on Adolf Wolf, I call B.S. I don’t know where the tale started but as the U.S. was fully involved in the war at the time the cartoon was made, the whole thing sounds like it was cooked up by someone who didn’t like Quimby or thought it was a funny story. Add in the fact Quimby was supervising the studio’s training films for the Army Air Corps. Oh, and at the time, Quimby had his son in a military academy.

As hard as it is to believe, Avery got even more attention for the next cartoon he put into production—another fairy tale parody. It was

Red Hot Riding Hood.

Felix Gets Revenge, Sept. 1, 1922

Felix Gets Revenge, Sept. 1, 1922 In 1934, while an usher at Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition, gleeful Bill won an NBC audition and was put under contract to the network. His first appearance on a network show was on the National Farm and Home Hour.

In 1934, while an usher at Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition, gleeful Bill won an NBC audition and was put under contract to the network. His first appearance on a network show was on the National Farm and Home Hour.  TODAY, THOMPSON is public service representative of the Union Oil Company, a West Coast firm that allows Thompson to make his good will talks around the country. Herbert Hoover has appointed him national director of the Boys' Clubs of America, and Thompson, in turn, is elated at landing his old boss, Walt Disney, on the board.

TODAY, THOMPSON is public service representative of the Union Oil Company, a West Coast firm that allows Thompson to make his good will talks around the country. Herbert Hoover has appointed him national director of the Boys' Clubs of America, and Thompson, in turn, is elated at landing his old boss, Walt Disney, on the board.

A little over a month after Pearl Harbor, The Hollywood Reporter revealed “As his first cartoon supervising chore at MGM, Fred ‘Tex’ Avery will handle ‘Blitz Wolf,’ a new animated character for the studio’s shorts” (Jan. 16, 1942). The paper announced on June 2 the cartoon was “in last stages of work” and on Aug. 19 it was “winding up production.” It wound up pretty fast as the same day, the Academy of Motion Pictures screened it at the Filmarte Theatre.

A little over a month after Pearl Harbor, The Hollywood Reporter revealed “As his first cartoon supervising chore at MGM, Fred ‘Tex’ Avery will handle ‘Blitz Wolf,’ a new animated character for the studio’s shorts” (Jan. 16, 1942). The paper announced on June 2 the cartoon was “in last stages of work” and on Aug. 19 it was “winding up production.” It wound up pretty fast as the same day, the Academy of Motion Pictures screened it at the Filmarte Theatre.

I have a hard time believing Quimby said this, even if he were joking (Quimby was not known for having a sense of humour). Hollywood—as was all of America—was awash with extreme anti-Axis patriotism. And Jones was not exactly known for a kindly attitude toward cartoon film producers (Disney, excepted).

I have a hard time believing Quimby said this, even if he were joking (Quimby was not known for having a sense of humour). Hollywood—as was all of America—was awash with extreme anti-Axis patriotism. And Jones was not exactly known for a kindly attitude toward cartoon film producers (Disney, excepted).

Daily Variety told readers on January 16, 1942 about a cartoon. “Fred Avery will supervise production of ‘Blitz Wolf,’ cartoon subject at Metro.”

Daily Variety told readers on January 16, 1942 about a cartoon. “Fred Avery will supervise production of ‘Blitz Wolf,’ cartoon subject at Metro.”

The Hollywood Reporter quoted Fred Quimby as stating on August 18th the cartoon was “winding up production.” If so, it wound up very fast. The press got a sneak preview the next night at the Filmarte Theatre by the Motion Picture Academy. It was the last short to be screened, and the programme included Superman’s Terror of the Midway, the very good Norm McCabe war short The Duck-Tators, Goofy in The Olympic Champ and the Fox and Crow in Woodman, Spare That Tree. About all Daily Variety said about it was “solid laughs.” The Reporter pronounced it “an especially ingenious release.”

The Hollywood Reporter quoted Fred Quimby as stating on August 18th the cartoon was “winding up production.” If so, it wound up very fast. The press got a sneak preview the next night at the Filmarte Theatre by the Motion Picture Academy. It was the last short to be screened, and the programme included Superman’s Terror of the Midway, the very good Norm McCabe war short The Duck-Tators, Goofy in The Olympic Champ and the Fox and Crow in Woodman, Spare That Tree. About all Daily Variety said about it was “solid laughs.” The Reporter pronounced it “an especially ingenious release.”

And Canada loved the cartoon, too. The Hollywood Reporter revealed on April 1, 1943 “For its Fourth Victory Loan Drive, starting April 15, the Canadian government will distribute MGM’s cartoon, ‘The Blitz Wolf,’ which was also used as a war bond sales stimulant in this country. W.H. Burnside, director of production for the National Film Board of Canada, is here [in Los Angeles] making arrangements for 195 (16mm.) and 65 (35mm.) prints. The negative was furnished gratis by MGM.” This didn’t mean theatres. The cartoon was shown with other NFB propaganda films on a screen at Eaton’s in downtown Toronto every hour, seven times a day, in April 1944. In Vancouver and Victoria, “bond” shells were set up downtown where the cartoon played for anyone passing by.

And Canada loved the cartoon, too. The Hollywood Reporter revealed on April 1, 1943 “For its Fourth Victory Loan Drive, starting April 15, the Canadian government will distribute MGM’s cartoon, ‘The Blitz Wolf,’ which was also used as a war bond sales stimulant in this country. W.H. Burnside, director of production for the National Film Board of Canada, is here [in Los Angeles] making arrangements for 195 (16mm.) and 65 (35mm.) prints. The negative was furnished gratis by MGM.” This didn’t mean theatres. The cartoon was shown with other NFB propaganda films on a screen at Eaton’s in downtown Toronto every hour, seven times a day, in April 1944. In Vancouver and Victoria, “bond” shells were set up downtown where the cartoon played for anyone passing by.