Jack Benny gave a lengthy, wide-ranging interview to Broadcasting • Telecasting magazine that was published on October 15, 1956, discussing how and why he entered radio and television, writing his show, and his sponsorship and network changes.

Some of the answers seem a little unusual. Benny quit General Foods for American Tobacco solely because he wanted to plug a different product? Going back to when it happened, the trade press reported he wasn’t altogether happy with General Foods. And he completely ignores his sponsorship by Chevrolet. Benny expert Graeme Cree points out this wasn’t the only time he snubbed the carmaker in later years and believes it was intentional. If you don’t know, against the wishes of many Chevy dealers, the company’s president dumped the Benny show because he wanted a musical programme instead.

Note in 1948 how Benny (rather MCA) shrewdly sold CBS the Jack Benny radio show, not Benny and his characters. In a few years, Benny was free to negotiate another deal strictly for television under a different production company, maintaining all the characters of his radio show. Think of how, years later, David Letterman left NBC for CBS but NBC retained the rights to Larry ‘Bud’ Melman.

STARS SHINE BEST WHEN POLISHED

NO PERFORMER in broadcasting has kept at or near the top as consistently or long as Jack Benny. Here, in this recorded interview with B*T's Associate Editor Larry Christopher, Mr. Benny explains how he has kept his star shining for nearly 25 years.

Q: Jack, since you have sustained about the longest run on radio and television of a single personality during the past quarter of a century, your impressions are of special significance to the broadcasting profession at this time. For instance, how did you happen to decide to leave radio and devote full time to television?

A: I didn't have to decide. Television decided that for you. Tv and sponsors. There's no such a thing as making a decision there. You go where you have to go.

Q: The decision is not up to the entertainer?

A: No. Not at all. I don't care how good your radio program is at the moment, if you have to make a transition to television and if you don't make a good one, it certainly isn't good for the star.

Q: What are the problems for the star in making the transition?

A: Some people might be very, very good in radio and not make it in television because maybe before radio they haven't had real show business experience. On the stage. You see, television brings you back on the stage. I fortunately have had many, many years of experience on the stage, including vaudeville. Now, on the stage I used to do practically what Ed Sullivan does today except he goes for it pretty straight and I go for comedy. If I had started years ago and done that type of show, that would have been the type of show I would be doing today. Now that would have been easy for me to do — a weekly show as an m.c. As long as I knew the acts that were coming in I could prepare for it and also do some work with them. Outside of that, on my first year I sort of had to feel my way around and it seemed that the oftener I did them the better the shows were because I got into the groove like I did on radio.

Q: You're on your seventh year in tv on CBS-TV and with greater frequency than before, are you not?

A: For the last three years it's been every other week. Before that, once a month. Before that, once every six weeks. Before that, six a year and before that four a year. The fewer you do the tougher they are.

Q: The frequency keeps you sharper?

A: Not only keeps you sharper but you don't feel the responsibility that you have when you only go on four times.

Q: Did you feel a more significant responsibility?

A: Yes. If you only go on four times then every show has to be a knockout. This way, the way I go on now, if every show isn't great it doesn't make that much difference. I try to keep them great. Or let me say, I try to keep them from being lousy!

Q: Do you feel television is draining on your creative capacity much more than radio, the movies or vaudeville did?

A: I think it's a big drain on people. I must say fortunately it's been a little easier for me because of the build-up of the characterization over a period of years. This gives the writers something to hang on to. So that even though every program is different, it has something to do with my character and it isn't quite as tough to write. By that I mean you don't have to start off and say "let's write a show" like you do with some comedians who are fine and great comedians but haven't established characterizations. So when you start to write for them, you have to write a great show from the start that maybe has nothing to do with the fellow's character particularly.

Q: The impact of radio reaching such a mass audience, and later television adding its visual impact, these have been a vital factor in establishing this characterization, have they not?

Of course. It's the whole thing.

Q. You mentioned Ed Sullivan. Didn't you make your first radio appearance on his NBC show in 1932?

A. Yes, that's right. That's where they first heard me.

Q: How did it happen?

A: I had known Ed Sullivan for a long time and he asked me to be a guest on his radio show. At that time I was doing shows in New York in vaudeville. Vaudeville was beginning to die.

Q: Did you make a free appearance or for pay?

A: I don't recall. But the agency for Canada Dry ginger ale heard me and called me and gave me a job. We went on then for 39 weeks.

Q: What was your first reaction to this new medium after so many years on the stage?

A; Well, the reaction was a little bit frightening because in vaudeville you had one show and that was it. You changed it whenever you felt like it. And in this, when you realized that every week you needed a new show, this got a little bit frightening. But you storm through it some way because everybody is in that same spot.

Q: As a talent personality, what was it like to find yourself looking to a sponsor instead of a box office? Did you meet the Canada Dry people?

A: Oh sure. But I don't recall our first meeting. All I recall is leaving the stage show. You see, I was always looking ahead for something. Sometimes I left good jobs. I didn't have much money in those days. I was making good money, but I used to spend it all. But I always looked ahead. And I said, "If this is the new medium, then I must get into it." So I left the stage show, Earl Carroll's Vanities. I asked for my release from a show for which I was getting $1,500 a week. This was a lot of money in those days. And I left to try and get into radio. I didn't even have a job. I turned down $1,500 a week and didn't have a job. My wife agreed with me that I was doing the right thing. As a matter of fact, she sort of encouraged it. She said if it's the thing to do to get into radio, then get into it. Don't worry, she said, they'll find you someplace.

Q: Was radio inevitable in your mind?

A: There is probably no doubt even had I finished the season I would have gotten into radio sometime. But I realized while I was with the show that names we had never heard of before had become more popular around the country than we who had been in show business all of our lives. Some of these people had no background of show business. It was just the fact they were hitting the whole country all at once. So I thought, well, if these people are in it without any great backgrounds and have a bigger reputation than any of us around the country who have worked in show business all of our lives, this is the business to get into . . . And the only reason I got a release from the Vanities is because they were going back to the small cities after leaving New York and Earl Carroll at that time probably was very happy to lose me at $1,500.

Q: Who were some of the people who helped you develop your early radio shows?

A: The first writer I had was a fellow called Harry Conn. A very, very good writer. I had one writer only.

Q: Was Harry Conn responsible for developing some of your original characteristics so well known as your program personality?

A: Well, I would say this. That a writer falls into your characterizations because even in vaudeville I had some of these traits. But they were developed more in radio.

Q: You are known as the man who made a success of integrating the commercial into the format.

A: That's right. Well, I'll tell you a story about that. The first few weeks that we did it in a satirical way on the Canada Dry show the sponsor didn't like it and wanted us to stop it.

Q: Was that the nickel back on the bottle gag?

A: That's right. We did a lot of satires on the commercials.

Q: What was the first notice of the sponsor not liking it?

A: The sponsor wanted us to go back to the straight commercial, but the agency liked it and the agency said "they haven't had time to prove whether this is a good way to do it." So they allowed us another two or three weeks. And in the next two or three weeks the mail kept coming in so much to the sponsor that they liked this kind of advertising that they finally let us alone and let us do it. That is the only way that I would ever do it. Unless I had certain shows where it can't be integrated.

Q: With radio's impact on this new mass audience, you also soon learned you could develop star personalities quickly, new names like your wife Mary, singers Frank Parker, Kenny Baker, Dennis Day, Rochester and Schlepperman and Mr. Kitzel.

A: That's right. They had to have a certain amount of talent right away. They had no chance to develop it any place.

Q: The medium gave them the opportunity . . .

A: Yes, but the medium didn't give them the opportunity to improve themselves. Not like vaudeville where they would play certain towns, if they were bad in one town that was the only town that would know it and then they could go on to another town and improve. You know, I could have been bad in South Bend or Lafayette and by the time I got to Chicago a few weeks later I might have been a little bit better. But on radio, everybody had to be good right away and it's even more so on television.

Q: You had an experience of that in television last year when Leigh Snowden walked across the stage in San Diego.

A: She just walked across the stage. We've had some people who have been developed, but then most of them have to have some talent themselves. There's no question, you can't develop an untalented person. You might develop them for about 10 minutes, but I don't think that you can do anything with them if they haven't got talent.

Q: What do you do to help sustain talent and creative capacity? The demand is tremendous, isn't it?

A: We don't do anything. We just go along as we are. We make no effort to try to be exceptionally good and we don't try to make an effort to top any former show. We try to be good. If we had a great show last week, that doesn't mean that the next one we have to knock our brains out. As a result, the next one can be better because we haven't done that. We never did that on radio. Oh, sometimes I do a show with the Ronald Colmans. People say, "are you going to top it?" Well, I say, we're not even going to try. We just have a show. You may like this one without the Colmans better this particular week.

Q: You can't please everyone all the time.

A: That's right. And people aren't interested in that as much as whether they like you and your cast as personalities.

Q: The feeling of friendship and identification?

A: Absolutely. We always try to have good shows, but we don't knock ourselves out.

Q: One thing that has always distinguished your program in radio and now tv is the precision-like attitude given to each detail in its planning and follow through.

A: Editing. I think editing is the most important thing in all show business. I think editing is the most important thing in anything you do, whether you're making a speech, in politics, I don't care where you are. There isn't a first show that we write that would be good enough to go on. Editing is the most important thing that we do.

Q: After editing, what factors do you consider most important?

A: Well before editing there is something even before editing. Having good, likeable people, good personalities that the audience likes. There are these things. Then, after you get them, good writers, I'm saying after you get all this together, then comes editing.

Q: You stick pretty close to script after this final editing, don't you?

A: We take advantage of the situation for ad libs, but I don't think ad lib comedy is nearly as good as what you write. I would much prefer to get a laugh on what I've worked on all week and what I've paid a lot of money for than to get a laugh on something I might say in the middle of a program when something happens. However, if something happens in the middle of a program, then I think you should take advantage of it. When you've paid for it you don't want to drop it. I'd like to see some show go on and not write anything and ad lib it and see how far they would get. I don't think Will Rogers could have done that, or Mayor Walker, who was probably the greatest ad lib speaker in the world.

Q: Another aspect of this, touching on your current tv show, you do both live and film programs. Do you have a preference?

A: I like doing live shows. I like the intimacy of a live show, but it all depends on what type of a show it is. I'm getting a little more intimacy in the films now that I've made a few. At first it was a bit difficult.

Q: What is your technique of intimacy?

A: I'm talking about walking out and really addressing an audience instead of a camera.

Q: Is that difficult for an entertainer?

A: I think it is. Some people do it very well, like George Burns, who's had this experience for so many years. But of course, when we do a live show we do it a little differently than most of them. We don't have any cameras on the stage at all. Our cameras are in the back of the audience. So when I say intimate, I mean intimate. We're as close to an audience as we can get and they just sit and watch us as though you were watching a play at the Biltmore Theatre.

Q: What are the steps leading up to your show, its conception and planning. For instance, take your kickoff show on CBS-TV for Lucky Strike.

A: We just try and see what would make a good opening show. What's a good idea for an opening show. How would you open a season? I was going to New York after this first show to give a concert at Carnegie Hall for charity October 2. So we figured a good opening would be something that had to do with Carnegie Hall, with my going, with my preparing for it, you see. So we wrote along these lines.

Q: Your writing team has been with you a long time, hasn't it?

A: Sam Perrin and George Balzer have been with me, I think, going on 14 years and Al Gordon and Hal Goldman about eight years. We sit down here in my office in Beverly Hills and we knock off the idea. Some agree and some disagree on some of the different points. When we get to the point where we all agree, then, we discuss the steps of the show. How we should open. They then go away and they write it and then bring it back and we edit it. We go over it very carefully. Next we have our first reading here or at CBS and then I edit it again.

Q: Who is your producer and director.

A: Ralph Levy is director and executive producer and Hillard Marks is producer. We usually rehearse Friday, Saturday and Sunday and do the show Sunday.

Q: Getting back to your early radio show, after the initial 39 weeks for Canada Dry, where did the sponsorship go?

A: It went to General Tire, but just for about six months. It was a summer product. Next we switched to General Foods and six delicious flavors of Jello for many, many years.

Q: By 1940, it seems, the demand for Jello had been so built up by your program that there wasn't enough product to go around and the sponsor was required to put on another product. Isn't that true?

A: I think that finally the last couple of years they switched to Grape Nut Flakes. When we first took over for Jello, the product wasn't selling.

Q: Do you recall when the sponsor first expressed approval at the way radio was moving Jello off the dealer's shelf?

A: It took about the first season for them to realize that the product now was becoming very, very important.

Q: How long did you stay with General Foods?

A: About 10 years. It was in 1944 when I switched to Lucky Strike because I was in the South Pacific in '44 and when I came back I went with them.

Q: Why did you cancel your association with General Foods?

A: I just wanted to switch. I thought I should go with another product.

Q: About 1940-41, you had achieved a very unique thing with respect to your Sunday night 7 p.m. spot on NBC. You became the only personality in radio to control his own time period.

A: That's right. NBC gave me the time and as long as I was staying on it I could have the 7 o'clock period. Any sponsor who got me got that time.

Q: What were the steps leading up to this unique contract with NBC?

A: It came up because I had an opportunity to leave them. No. I'll tell you how it came up. I was going to leave General Foods the year before. That would have been 1940. I intended to leave my present sponsor and go with somebody else and my present sponsor wanted to keep the time whether I left him or not. So NBC came along and said if you will stick with General Foods this time we'll see that you'll always have 7 o'clock Sunday as your time. So I renewed with General Foods.

Q: Did Niles Trammell negotiate this for NBC?

A: Yes. But this was not contractual. This was merely a letter.

Q: When you dropped General Foods, how did you happen to sign with American Tobacco Co.?

SO, ON TO LUCKY STRIKE

A: There were five different companies that went after whatever deal we wanted. I don't recall at this time. The two of them we were trying to decide on were Campbell Soup Co. and American Tobacco and I finally picked Lucky Strike because of a man in the agency that I happened to know who represented Lucky Strike at that time, he sort of brought me over that way.

Q: Who was this person?

A: Don Stauffer.

Q: That was Sullivan, Stauffer, Colwell & Bayles then?

A: I believe so.

Q: Did you think this personal relationship was important for the best development of the show?

A: Well, I felt that I had one person whom I knew to work with should there be any problems. Because I used to hear at that time that the president of American Tobacco who was George Washington Hill was tough to work for. But we didn't find him that way at all. He was simply wonderful.

Q: Do you remember your first meeting with George Washington Hill?

A: Yes. I didn't meet him until about four months after I was working for him.

Q: Where was this?

A: I had lunch with him at his office. And he said a very, very wonderful thing to me. A very funny thing, let me put it that way. He knew he had a reputation for being tough, so as we sat down to have lunch he told me how much he enjoyed my programs. So I thanked him and told him that we always try to have good shows and that we were very fortunate on his show so far of having them pretty nearly all good, but sometimes we're not that lucky. He says to me, "Well, Mr. Benny, I only know one thing. Had your shows been bad, they never would have blamed you. They would say 'there's that so-and-so George Washington Hill to blame for that'."

Q: In later years you moved over to CBS and were one of the first to work out the capital gains arrangement so familiar throughout show business today. Like Amos 'n' Andy, the talent property became a business property, did it not?

A: That wasn't my case. My case was that I had a company and more than just my own show. We started on CBS Radio network Jan. 4, 1949. My company was Amusement Enterprises Inc. This is the company I sold. I didn't sell Jack Benny. I was just a stockholder in the company.

Q: The company itself packaged the programs and handled all the details of your activities?

A: That's right.

Q: I think this was one of the original capital gains arrangements in our profession. Wasn't the original case with General Eisenbook, which set the precedent after World War II, and then came Amos 'n' Andy?

A: Well, you see, Amos 'n' Andy had a legitimate deal because they themselves do not appear on any of their shows, so they have something all separate.

Q: They were selling the characterizations and you were selling a company?

A: I was selling a company with other shows. Like Let's Talk Hollywood. We had a movie, too. Whatever it was, the first year we had a profit-making company.

Q: What was perhaps the most influential factors in your decision to move from NBC to CBS?

A: To make some money like everybody else would like to make. That was the only reason. I was very happy at NBC. The deal was offered to NBC first. This was strictly a business deal for me to make some money. There is no way for an actor to make some money by getting a salary. If he depends on a salary, no matter how much he makes, he's going to go broke eventually. I wouldn't care if I worked for ABC, CBS, NBC or the American Trucking Co. if there was a chance for show business to make some money.

Q: The salary concept, then, has not been satisfactory . . .

A: . . . Oh, as far as earning, as far as salary was concerned, nobody could make any more money than I did. But suppose right now I make a half million dollars a week, let's go that broad; suppose I was given a half million dollars a week, but it was salary. What could I get out of it? About five dollars.

Q: While you were with NBC, I assume you got to know others in the NBC-RCA organization in addition to Niles Trammell. For instance, Gen. David Sarnoff?

A. Never met him until after I went to CBS.

Q. What was the occasion of your meeting General Sarnoff after you switched to CBS, do you recall?

A. Not at all.

Q: Had you met Bill Paley before you went to CBS?

A: Oh yes. I had known Bill Paley for some time. Bill Paley and I were friends without even discussing my ever moving to CBS.

Q: Had you known Dr. Frank Stanton previously?

A: No. Frank Stanton I only knew after I moved there. But Paley I'd seen a lot of at parties in New York. He might have said once, "I'd like to have you with us," and that would be the end of that.

Q: Your present contract with American Tobacco Co., is it coming up for renewal soon?

A: It's a yearly contract.

Q: Your characterization and comedy format through the years, Jack, have been unusually distinctive. Take Fred Allen, for example, your approach was different. Oh, I'm reminded of your big "fight" with Fred Allen. Didn't that start in 1936?

A: Something like that. It was an accident.

Q: Did you see immediate public reaction to this interplay?

A: No. As a matter of fact, we did it just as a gag between ourselves. It didn't start out to be a feud at all. It just started out with Fred Allen saying something which I picked up the next week and then he picked it up the next week and so on. The first thing we knew we had it. Of course, I've always said that if Fred Allen and I ever had gotten together and said "let's have a feud" it probably wouldn't have lasted a month as it would have been contrived. Imagine what Fred Allen, God rest his soul, would have said about my appearance at Carnegie Hall Oct. 2. If he knows anything about it now, he is talking plenty. Say, that would have been a good line to use at Carnegie Hall, wouldn't it?

Q: What, perhaps, was different about your approach to the transition from radio to television. Fred Allen never made the change. I think that's one of the saddest stories in show business, that a man of such great genius . . .

A: . . . Well, Steve Allen describes this very, very well in his book. That Fred Allen was one of the greatest writing and creative comedians in the business. He was a fine comedian, a great writer. Probably better than an acting comedian, you know. And so, therefore, it might have been difficult for him to find the right thing to do. But, sometimes, even he could have found it accidentally. He might have something right away that would have been great for television. Right away. But he just didn't happen to do it. But by the same reason he didn't, he also could have. He just didn't get into the right thing.

Q: Many of the other old timers in radio made the switch to tv and have had their problems. Eddie Cantor began a syndicated series for Ziv but had to give it up. He makes occasional appearances now.

A: Well, I think in Cantor's case his illness took a big toll there. You know, he had this bad heart attack a few years ago and then an operation before that. It's very tough to think and be able to be successful when you have these other worries on your mind. You're told not to do this and I imagine this would have quite an affect on anybody. A lot of his humor was physical too. Lots of jumping. No question he is a fine comedian.

Q: What about Danny Kaye's approach?

A: Well, he doesn't need anything. He doesn't need radio or television. His pictures, his personal appearances or wherever he goes, he does very big. He's a stylized kind of comedian who is excellent in what he does. He doesn't need any other facets of show business in order to stay one of the top comedians. Now, Bob Hope fits into everything.

Q: That takes considerable versatility.

A: Right. And energy. And he's got that. Besides, he's got a terrific personality and he's not only got a great wit but a great warmth in his personality. He finds time to do nice things for others. All together he's damn well liked. It's almost impossible for Bob to do the wrong thing. And if he does do any thing wrong, he's forgiven almost immediately.

Q: Your good friend George Burns has certainly found a successful home in tv.

A: True. And George Burns is a very, very creative comedian. He does what I do in the fact that he's always got his hand in everything. He's got his hand in it from the time they start on the show.

Q: This close attention is very necessary, isn't it?

A: I think very few comedians or stars can be successful and not be a part of the whole organization working to make it a success. Only in the movies can this happen.

Q: In the final analysis, the comedian has to deliver the entertainment product.

A: That's right. He either lives or dies with it.

Sunday, 30 April 2017

Saturday, 29 April 2017

UPA Acclaim

In the world of film, there’s room for comedy, drama, adventure, mystery—unless it’s an animated cartoon. In that case, critics (for the most part) decided there was no room for comedy or, if there was, it must be subtle and underplayed.

So it was that critics fell over themselves to expound on the “realistic art” of Walt Disney and then later the “adultness” of UPA.

The UPA story has been told in many places, the tale of a studio that was deliberately anti-Disney, anti-Warners, anti-funny animal, where graphics were important and, perhaps to some of its artists, the only thing that mattered.

I’m afraid I can take or leave pretty much all of UPA’s theatrical output. Mostly leave. The artists seem to be trying too hard to be different, trying too hard to be droll instead of funny. To be honest, the most enjoyable UPA cartoons I’ve seen are the studio’s TV commercials. They are droll, if not funny, and the drawing style is different without clobbering the viewer over the head about it. Mind you, UPA wasn’t the only studio experimenting with character (and background) design and movement in TV ads at the time.

The New York Herald Tribune published this little primer on the UPA studio on November 23, 1953, skipping its pre-history and starting with the Columbia release contract. It’s not an out-and-out rave but shows its appreciation. As you likely know, the Thurber feature talked about was never made. Columbia didn’t think Thurber was box office enough; the same logic that resulted in Mr. Magoo being plunked into the studio’s eventual Arabian Knights feature. And if Rooty Toot Toot was a “tremendous success with children,” it had nothing do with the story. Children soon showed CBS what they wanted—bargain-basement Terrytoons instead of the coy Boing-Boing Show.

The Animated Cartoon Becomes a Full-Fledged Art

Poe, Thurber Stories Made Into Films

By THOMAS WOOD

HOLLYWOOD, Nov. 22.—Four years ago a group of young animated-cartoon experts banded together for the express purpose of taking their product out of the pictures-for-kids or “cat and mouse” stage. They called their company UPA, for United Productions of America, and in the short time they have been active they have completely revolutionized the animated cartoon.

While their break with tradition was not clean—their first releasing contract called for three “Fox and Crow” cartoons—their initial effort, “Robin Hoodlum,” was so original and mature that it was given an exclusive run in the so-called “art circuit.”

Since then, UPA has ticked off many a cartoon milestone and won a gross of awards here and abroad. In 1950, for instance, three of its nearsighted Mr. Magoo films were selected for exhibitions at Edinburgh.

That same year the company won its first Academy Award for “Gerald McBoing Boing,” a highly imaginative cartoon about a little boy who spoke sound effects rather than words. And last year it received an Oscar nomination for “Rooty Toot Too,” a lusty interpretation of the famous legend of Frankie and Johnny, but was beaten in the award by a “Tom and Jerry” picture.

“Rooty Toot Toot” is regarded around the company’s tiny studio in Burbank as the turning point in its history. The subject matter, which is concerned largely with sex, lust and murder, was a distinct departure from anything ever dealt with in animated cartoons. Its tremendous success, both with grown-ups and children, paved the way for further explorations into uncharted fields.

One example of UPA’s new adventures is a cartoon translation of a contemporary literary classic, Ludwig Bemelmans’ “Madeline” (recently shown in New York). This is the story of twelve little schoolgirls in Paris who do everything in unison like brushing their teeth, smiling at good deeds and frowning at bad ones. They live such identical lives that when one gets appendicitis, the others all want it, too.

This unusual project has been approached with great reverence. Bemelmans’ unique art style has been faithfully followed throughout. Some of the colors have been intensified here and there, perhaps, but the end result is as typically Bemelmans as if the artist-author had animated it himself.

Soon UPA will release two other animated cartoons which also are visual counterparts of famous stories—“The Tell-Tale Heart,” by Edgar Allan Poe, and a fable of our time, “The Unicorn in the Garden,” by James Thurber.

The art approach in each instance has been set by the tone of the original. Poe’s story is ghoulish and somber, so the characters and the settings take on some of the atmosphere of a Charles Addams’ drawing. This film has been a labor of love in this respect, for the artists at UPA are extremely fond of Addams’ work, and some day they hope to bring some of his sinister people to the screen.

Light, Gay Fable

As for the Thurber fable, it is light and gay, like his drawings, and the animators have simply assimilated his style. Some minor liberties have been taken with the colors, though, because there is no evidence that Thurber ever worked in anything but black and white. But if he had, the UPA artists feel certain that he would have used colors as sparingly as they have. Similarly, they have applied sloppy washes to the backgrounds on the simple theory that if Thurber had ever attempted to fill in his backgrounds, he’d have been sloppy about it.

UPA is pinning great hopes on its Thurber picture, by the way, because if it is successful, the company hopes to follow it up with a full-length feature based on his famous “Battle of the Sexes.” Some time ago, they took an option on this work but haven’t yet been able to raise the necessary backing, which is estimated at $500,000.

Despite the acclaim which greets its work, UPA has not yet broken down the distributors’ resistance to full-length animated cartoons of a non-“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” character, but the company doesn’t intend to give up trying.

So it was that critics fell over themselves to expound on the “realistic art” of Walt Disney and then later the “adultness” of UPA.

The UPA story has been told in many places, the tale of a studio that was deliberately anti-Disney, anti-Warners, anti-funny animal, where graphics were important and, perhaps to some of its artists, the only thing that mattered.

I’m afraid I can take or leave pretty much all of UPA’s theatrical output. Mostly leave. The artists seem to be trying too hard to be different, trying too hard to be droll instead of funny. To be honest, the most enjoyable UPA cartoons I’ve seen are the studio’s TV commercials. They are droll, if not funny, and the drawing style is different without clobbering the viewer over the head about it. Mind you, UPA wasn’t the only studio experimenting with character (and background) design and movement in TV ads at the time.

The New York Herald Tribune published this little primer on the UPA studio on November 23, 1953, skipping its pre-history and starting with the Columbia release contract. It’s not an out-and-out rave but shows its appreciation. As you likely know, the Thurber feature talked about was never made. Columbia didn’t think Thurber was box office enough; the same logic that resulted in Mr. Magoo being plunked into the studio’s eventual Arabian Knights feature. And if Rooty Toot Toot was a “tremendous success with children,” it had nothing do with the story. Children soon showed CBS what they wanted—bargain-basement Terrytoons instead of the coy Boing-Boing Show.

The Animated Cartoon Becomes a Full-Fledged Art

Poe, Thurber Stories Made Into Films

By THOMAS WOOD

HOLLYWOOD, Nov. 22.—Four years ago a group of young animated-cartoon experts banded together for the express purpose of taking their product out of the pictures-for-kids or “cat and mouse” stage. They called their company UPA, for United Productions of America, and in the short time they have been active they have completely revolutionized the animated cartoon.

While their break with tradition was not clean—their first releasing contract called for three “Fox and Crow” cartoons—their initial effort, “Robin Hoodlum,” was so original and mature that it was given an exclusive run in the so-called “art circuit.”

Since then, UPA has ticked off many a cartoon milestone and won a gross of awards here and abroad. In 1950, for instance, three of its nearsighted Mr. Magoo films were selected for exhibitions at Edinburgh.

That same year the company won its first Academy Award for “Gerald McBoing Boing,” a highly imaginative cartoon about a little boy who spoke sound effects rather than words. And last year it received an Oscar nomination for “Rooty Toot Too,” a lusty interpretation of the famous legend of Frankie and Johnny, but was beaten in the award by a “Tom and Jerry” picture.

“Rooty Toot Toot” is regarded around the company’s tiny studio in Burbank as the turning point in its history. The subject matter, which is concerned largely with sex, lust and murder, was a distinct departure from anything ever dealt with in animated cartoons. Its tremendous success, both with grown-ups and children, paved the way for further explorations into uncharted fields.

One example of UPA’s new adventures is a cartoon translation of a contemporary literary classic, Ludwig Bemelmans’ “Madeline” (recently shown in New York). This is the story of twelve little schoolgirls in Paris who do everything in unison like brushing their teeth, smiling at good deeds and frowning at bad ones. They live such identical lives that when one gets appendicitis, the others all want it, too.

This unusual project has been approached with great reverence. Bemelmans’ unique art style has been faithfully followed throughout. Some of the colors have been intensified here and there, perhaps, but the end result is as typically Bemelmans as if the artist-author had animated it himself.

Soon UPA will release two other animated cartoons which also are visual counterparts of famous stories—“The Tell-Tale Heart,” by Edgar Allan Poe, and a fable of our time, “The Unicorn in the Garden,” by James Thurber.

The art approach in each instance has been set by the tone of the original. Poe’s story is ghoulish and somber, so the characters and the settings take on some of the atmosphere of a Charles Addams’ drawing. This film has been a labor of love in this respect, for the artists at UPA are extremely fond of Addams’ work, and some day they hope to bring some of his sinister people to the screen.

Light, Gay Fable

As for the Thurber fable, it is light and gay, like his drawings, and the animators have simply assimilated his style. Some minor liberties have been taken with the colors, though, because there is no evidence that Thurber ever worked in anything but black and white. But if he had, the UPA artists feel certain that he would have used colors as sparingly as they have. Similarly, they have applied sloppy washes to the backgrounds on the simple theory that if Thurber had ever attempted to fill in his backgrounds, he’d have been sloppy about it.

UPA is pinning great hopes on its Thurber picture, by the way, because if it is successful, the company hopes to follow it up with a full-length feature based on his famous “Battle of the Sexes.” Some time ago, they took an option on this work but haven’t yet been able to raise the necessary backing, which is estimated at $500,000.

Despite the acclaim which greets its work, UPA has not yet broken down the distributors’ resistance to full-length animated cartoons of a non-“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” character, but the company doesn’t intend to give up trying.

Labels:

UPA

Friday, 28 April 2017

Wile E. Cat

You remember that cartoon where Wile E. Coyote tip-toed from right to left carrying something, giving a knowing side look to the camera before entering his cave?

Oh, wait. This is Wile E. Coyote wearing a Tom costume. Isn’t it?

The cartoon starts with Jerry mouse drinking some kind of potion that makes him as fast as a, um, roadrunner. About the only thing missing in Is There a Doctor in the Mouse (1964) is a pile of purchases from the Acme Company.

We get Warners directors, Warners artists, a Warners writer, Warners sound effects and even Warners voices. We also get a slick-looking cartoon that’s really boring.

Oh, wait. This is Wile E. Coyote wearing a Tom costume. Isn’t it?

The cartoon starts with Jerry mouse drinking some kind of potion that makes him as fast as a, um, roadrunner. About the only thing missing in Is There a Doctor in the Mouse (1964) is a pile of purchases from the Acme Company.

We get Warners directors, Warners artists, a Warners writer, Warners sound effects and even Warners voices. We also get a slick-looking cartoon that’s really boring.

Labels:

Chuck Jones,

MGM

Thursday, 27 April 2017

More Fun Than a Barrel of Skeletons

Mickey Mouse encounters skeletons galore in The Haunted House (1929). In fact, he plays the organ for them as they dance and use bones to play each other like xylophones.

Then he tries to escape. A doorknob turns into a skeleton.

A door hides a Murphy bed containing husband/wife skeletons. Mickey jumps out the upstairs window. He lands into a barrel where the water turns into skeletons.

Mickey shakes his head looking around so quickly, he practically grows a second head. This is an early version of smear animation, it would appear.

Ub Iwerks is the only credited animator.

Then he tries to escape. A doorknob turns into a skeleton.

A door hides a Murphy bed containing husband/wife skeletons. Mickey jumps out the upstairs window. He lands into a barrel where the water turns into skeletons.

Mickey shakes his head looking around so quickly, he practically grows a second head. This is an early version of smear animation, it would appear.

Ub Iwerks is the only credited animator.

Labels:

Walt Disney

Wednesday, 26 April 2017

Children of the Radio

For every Ron Howard, who people watched as a young child and followed his show business career into adulthood, there are a bunch of Muriel Harbaters.

Muriel, for those of you who don’t know, co-starred on the radio show “Jolly Bill and Jane” in the late 1920s and early ‘30s on NBC. She was under 10 when she started. She quit the show in 1935. By 1940 was toiling as an office worker for a wholesale stationery company. The show biz in her blood turned anaemic.

Here’s a neat story from the National Enterprise Association from 1931 talking about the child stars on the radio at the time. Two of the people in the story you’ll likely have heard of; they took their careers into adulthood. After childhood, Rose Marie sang and did impersonations in nightclubs, then landed the role she’ll always be known for on The Dick Van Dyke Show. Walter Tetley may have had the biggest radio career of the lot of the young people listed, with regular roles on The Fred Allen Show, then The Great Gildersleeve, then The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show. When television came around, he voiced Sherman in the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons, and that’s probably how you know him best.

The others in the story below had varying degrees of a post-kid life in entertainment. Jimmy McCallion won bit roles in movies and TV. Conversely, I can’t find a thing about Bobby Jane Allert outside this story; I wonder if the author got the name right. And we hope the story is correct and young Muriel retired to a life of independent wealth from her glamour days with Jolly Bill.

Child Radio Artists Outdo Their Dads as Money Earners; Broadcasting Offers New Field for Talented Baby Stars

By PAUL HARRISON

NEA Service Writer

NEW YORK, Feb. 13. (NEA)—In more ways than one is radio an infant industry. Scores of its artistic little proteges, many of them too young to read their scripts before the microphone, are bringing home bankrolls that make their fathers' salaries look like pin money.

The young idea in the broadcasting business had twisted an old maxim around to "Children should be heard, and not seen"—but the sooner television comes along, the better they'll be satisfied. For talented children are adopting the radio as their own special medium, and another decade or two will find hundreds of highly-paid entertainers who literally have made broadcasting their life work.

Just now, with most of the baby stars, a radio career is pretty much in the nature of a lark. The sights they see in the labyrinthine studios, the rehearsals which are scarcely more than afternoon parties, and the stories and plays in which they take part all are far more exciting than their pay-checks.

As a matter of fact, their salaries are not large in comparison to those of adult performers and, contrary to reports of fabulous amounts and long term agreements, only one young star today is working under contract to a broadcasting company. This is Baby Rose Marie, 7-year-old bundle of hard-boiled precocity, love-crooning, blues-shouting tenement-house daughter of an Italian father and a Polish mother. Their name used to be Mazetta; it's Curley now, and they're managing Rose Marie, teaching her jazz songs and banking something less than $1000 weekly from a vaudeville contract. She has been in the movies, too, and soon will return to the air.

But though many of radio's baby stars are the children of foreign-born parents, few are such unchildlike sophisticates. Winifred Toomey, for instance, an Irish colleen of 10 who has had six years of broadcasting experience. Apparently as simple and unaffected as any youngster of her age, she plays most of the important little-girl parts you hear over the NBC networks. She attends a professional children's school, is a full-fledged actress and earns about $5000 a year.

Winifred has an Irish partner in many of her broadcasts, Jimmy McCallion, 11, who is more of a child of the stage. Jimmy has appeared in several Broadway shows, has had parts in 25 movies, and began his radio career four years ago. He makes a lot more money than Winifred.

Radio Is Play to Him

"Radio is just a lot of fun," said Jimmy seriously. "It's mostly like playing with a bunch of kids at your own house. The movies are just hard work, but I like the stage because I can tell when people like me.

Another highly-paid baby star is Muriel Harbater, who is "Jane" with "Jolly Bill" Steinke on NBC networks every morning. She is the daughter of a plumber in the Bronx who is sticking to his pipes and faucets while Mrs. Harbater manages Muriel and makes sure that her education doesn't suffer. It's a strict routine, rising at 5 o'clock every morning and doing two broadcasts at the studio, but all of her salary is being banked against the time she is of college age and should be independently wealthy.

Miss Madge Tucker, who directs the juvenile activities of the National Broadcasting Company, manages and acts in the widely-known "Lady Next Door" program. Since she deserted the stage for radio six years ago, she has given thousands of children has given thousands of children's auditions and has discovered most of today's youthful entertainers. About 75 of them appear regularly on the programs she supervises.

"And practically every one of them,” she declared, “is the child of hard-working parents who never would dream of exploiting their youngster’s talent. There is some jealousy, of course, but generally we get along better than adult entertainers.

“The children themselves are quicker to learn than most grown-ups. Their charm is in their naturalness for they seldom try to ‘act.’ I treat them like intelligent people because they are. Pure animal spirit sometimes makes them a little unruly at rehearsals but they really take pride in their discipline and almost never show stage-fright.”

Miss Tucker and Miss Nila Mack, director of children’s programs for the Columbia Broadcasting System, both predict that nearly all of their audition discoveries will go far in the entertainment world. There is Walter Campbell Tetley, the “Wee Harry Lauder” of NBC, who was discovered only a year ago and already is appearing regularly in four programs, including “Raising Junior” and Ray Knight’s Cuckoos. Another, Eddie Wragge, (“Shrimp” to you) is 10, tiny and blond, but he already has experience with the Theater Guild.

Howard Merril, at 14, has appeared in scores of movies and plays and is considered one of the best child actors on both Columbia and National Broadcasting programs. Pat Ryan, 10, and Estelle Levy, 8, principals in the “Helen and Mary” broadcast on the Columbia network, both are audition discoveries and come from modest New York homes. Bobby Jane Allert, 4, who has to memorize her script and songs, plays a ukulele almost as big as herself.

When a shabby little Russian girl of 8 walked into the Columbia studio for an audition recently and nearly shattered the microphone with her full-toned blues voice, the orchestra laid down its instruments and applauded. Her name is Ruby Barth, and you’ll be hearing her one of these days.

Their Incomes Vary

Alfred Corn, in NBC’s “Rise of the Goldbergs,” is 14 and gets heaps of fan mail. Laddie Seman [sic] of Norwegian and Dutch parents, has had theatrical experience and seems destined to go far. Donald Hughes, another veteran of 12, has graduated from children’s programs to the very profitable role of Rollo in J.P. McEvoy’s skit on the Columbia network.

But radio's babies have their ups and downs, for only a fortunate few have contracts on commercial programs. Others are "at liberty" for small bits which may last months or only a day. Jimmy McCallion, for instance, until recently appeared in seven different programs on various networks, and made from $15 to $50 weekly with each of them. But some of the broadcasts have been discontinued, and now Jimmy isn't making any more than his papa!

While the field for child talent is growing, program directors say it by no means is keeping up with the host of prodigies whose parents are constantly seeking auditions. Chances are slim indeed for young geniuses of piano or violin, since nothing of their fresh young personalities can be conveyed through the ether. The demand is only for dramatic actors and singers, and not more than one in a hundreds of these is outstanding enough to win a place in broadcasting.

Muriel, for those of you who don’t know, co-starred on the radio show “Jolly Bill and Jane” in the late 1920s and early ‘30s on NBC. She was under 10 when she started. She quit the show in 1935. By 1940 was toiling as an office worker for a wholesale stationery company. The show biz in her blood turned anaemic.

Here’s a neat story from the National Enterprise Association from 1931 talking about the child stars on the radio at the time. Two of the people in the story you’ll likely have heard of; they took their careers into adulthood. After childhood, Rose Marie sang and did impersonations in nightclubs, then landed the role she’ll always be known for on The Dick Van Dyke Show. Walter Tetley may have had the biggest radio career of the lot of the young people listed, with regular roles on The Fred Allen Show, then The Great Gildersleeve, then The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show. When television came around, he voiced Sherman in the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons, and that’s probably how you know him best.

The others in the story below had varying degrees of a post-kid life in entertainment. Jimmy McCallion won bit roles in movies and TV. Conversely, I can’t find a thing about Bobby Jane Allert outside this story; I wonder if the author got the name right. And we hope the story is correct and young Muriel retired to a life of independent wealth from her glamour days with Jolly Bill.

Child Radio Artists Outdo Their Dads as Money Earners; Broadcasting Offers New Field for Talented Baby Stars

By PAUL HARRISON

NEA Service Writer

NEW YORK, Feb. 13. (NEA)—In more ways than one is radio an infant industry. Scores of its artistic little proteges, many of them too young to read their scripts before the microphone, are bringing home bankrolls that make their fathers' salaries look like pin money.

The young idea in the broadcasting business had twisted an old maxim around to "Children should be heard, and not seen"—but the sooner television comes along, the better they'll be satisfied. For talented children are adopting the radio as their own special medium, and another decade or two will find hundreds of highly-paid entertainers who literally have made broadcasting their life work.

Just now, with most of the baby stars, a radio career is pretty much in the nature of a lark. The sights they see in the labyrinthine studios, the rehearsals which are scarcely more than afternoon parties, and the stories and plays in which they take part all are far more exciting than their pay-checks.

As a matter of fact, their salaries are not large in comparison to those of adult performers and, contrary to reports of fabulous amounts and long term agreements, only one young star today is working under contract to a broadcasting company. This is Baby Rose Marie, 7-year-old bundle of hard-boiled precocity, love-crooning, blues-shouting tenement-house daughter of an Italian father and a Polish mother. Their name used to be Mazetta; it's Curley now, and they're managing Rose Marie, teaching her jazz songs and banking something less than $1000 weekly from a vaudeville contract. She has been in the movies, too, and soon will return to the air.

But though many of radio's baby stars are the children of foreign-born parents, few are such unchildlike sophisticates. Winifred Toomey, for instance, an Irish colleen of 10 who has had six years of broadcasting experience. Apparently as simple and unaffected as any youngster of her age, she plays most of the important little-girl parts you hear over the NBC networks. She attends a professional children's school, is a full-fledged actress and earns about $5000 a year.

Winifred has an Irish partner in many of her broadcasts, Jimmy McCallion, 11, who is more of a child of the stage. Jimmy has appeared in several Broadway shows, has had parts in 25 movies, and began his radio career four years ago. He makes a lot more money than Winifred.

Radio Is Play to Him

"Radio is just a lot of fun," said Jimmy seriously. "It's mostly like playing with a bunch of kids at your own house. The movies are just hard work, but I like the stage because I can tell when people like me.

Another highly-paid baby star is Muriel Harbater, who is "Jane" with "Jolly Bill" Steinke on NBC networks every morning. She is the daughter of a plumber in the Bronx who is sticking to his pipes and faucets while Mrs. Harbater manages Muriel and makes sure that her education doesn't suffer. It's a strict routine, rising at 5 o'clock every morning and doing two broadcasts at the studio, but all of her salary is being banked against the time she is of college age and should be independently wealthy.

Miss Madge Tucker, who directs the juvenile activities of the National Broadcasting Company, manages and acts in the widely-known "Lady Next Door" program. Since she deserted the stage for radio six years ago, she has given thousands of children has given thousands of children's auditions and has discovered most of today's youthful entertainers. About 75 of them appear regularly on the programs she supervises.

"And practically every one of them,” she declared, “is the child of hard-working parents who never would dream of exploiting their youngster’s talent. There is some jealousy, of course, but generally we get along better than adult entertainers.

“The children themselves are quicker to learn than most grown-ups. Their charm is in their naturalness for they seldom try to ‘act.’ I treat them like intelligent people because they are. Pure animal spirit sometimes makes them a little unruly at rehearsals but they really take pride in their discipline and almost never show stage-fright.”

Miss Tucker and Miss Nila Mack, director of children’s programs for the Columbia Broadcasting System, both predict that nearly all of their audition discoveries will go far in the entertainment world. There is Walter Campbell Tetley, the “Wee Harry Lauder” of NBC, who was discovered only a year ago and already is appearing regularly in four programs, including “Raising Junior” and Ray Knight’s Cuckoos. Another, Eddie Wragge, (“Shrimp” to you) is 10, tiny and blond, but he already has experience with the Theater Guild.

Howard Merril, at 14, has appeared in scores of movies and plays and is considered one of the best child actors on both Columbia and National Broadcasting programs. Pat Ryan, 10, and Estelle Levy, 8, principals in the “Helen and Mary” broadcast on the Columbia network, both are audition discoveries and come from modest New York homes. Bobby Jane Allert, 4, who has to memorize her script and songs, plays a ukulele almost as big as herself.

When a shabby little Russian girl of 8 walked into the Columbia studio for an audition recently and nearly shattered the microphone with her full-toned blues voice, the orchestra laid down its instruments and applauded. Her name is Ruby Barth, and you’ll be hearing her one of these days.

Their Incomes Vary

Alfred Corn, in NBC’s “Rise of the Goldbergs,” is 14 and gets heaps of fan mail. Laddie Seman [sic] of Norwegian and Dutch parents, has had theatrical experience and seems destined to go far. Donald Hughes, another veteran of 12, has graduated from children’s programs to the very profitable role of Rollo in J.P. McEvoy’s skit on the Columbia network.

But radio's babies have their ups and downs, for only a fortunate few have contracts on commercial programs. Others are "at liberty" for small bits which may last months or only a day. Jimmy McCallion, for instance, until recently appeared in seven different programs on various networks, and made from $15 to $50 weekly with each of them. But some of the broadcasts have been discontinued, and now Jimmy isn't making any more than his papa!

While the field for child talent is growing, program directors say it by no means is keeping up with the host of prodigies whose parents are constantly seeking auditions. Chances are slim indeed for young geniuses of piano or violin, since nothing of their fresh young personalities can be conveyed through the ether. The demand is only for dramatic actors and singers, and not more than one in a hundreds of these is outstanding enough to win a place in broadcasting.

Tuesday, 25 April 2017

Flapping Foggy

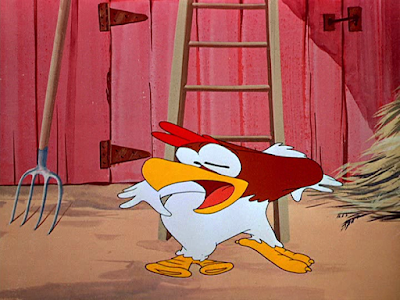

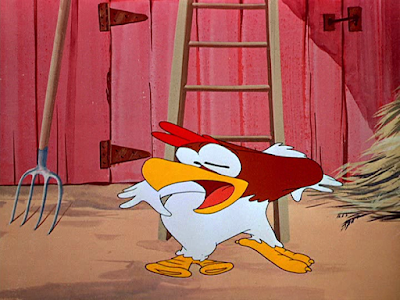

Violent gestures highlighted the early Foghorn Leghorn cartoons in the late 1940s before everything at Warner Bros. became fairly sedate.

Here’s Foggy not paying attention as he’s flapping his gums in The Foghorn Leghorn (1948). The dog gets the worst of it.

Foggy finally notices the dog. Here are some frames from the take.

Foghorn tries to escape from the angry dog. Check out the smear drawings as Foggy looks around before climbing the ladder.

There’s a lot of animation at the bottom of the ladder, too, as the rooster’s legs keep slipping off the rung. You sure didn’t see any action like that by the late ‘50s.

Read Devon Baxter’s research on this particular cartoon here.

Here’s Foggy not paying attention as he’s flapping his gums in The Foghorn Leghorn (1948). The dog gets the worst of it.

Foggy finally notices the dog. Here are some frames from the take.

Foghorn tries to escape from the angry dog. Check out the smear drawings as Foggy looks around before climbing the ladder.

There’s a lot of animation at the bottom of the ladder, too, as the rooster’s legs keep slipping off the rung. You sure didn’t see any action like that by the late ‘50s.

Read Devon Baxter’s research on this particular cartoon here.

Labels:

Bob McKimson,

Warner Bros.

Monday, 24 April 2017

Maybe It Does Strike Twice

“The Boy Scout Book says never stand under a tree in a lightning storm,” Droopy informs Spike in Droopy’s Good Deed. Lightning happily obliges to prove the point.

“It says, however, lightning never strikes twice in the same place,” Droopy continues, convincing Spike it’s safe to go back to where the tree was hit. The result is a gag edited for American television (that is, if Tex Avery cartoons still appear anywhere on American television). Scott Bradley plays “Swanee River” in the background.

There’s an odd frame that slipped through production that’s x’d out. The only way you’d see it is if you freeze-framed the cartoon.

Tex’s animators in this cartoon are Mike Lah, Walt Clinton and Grant Simmons.

“It says, however, lightning never strikes twice in the same place,” Droopy continues, convincing Spike it’s safe to go back to where the tree was hit. The result is a gag edited for American television (that is, if Tex Avery cartoons still appear anywhere on American television). Scott Bradley plays “Swanee River” in the background.

There’s an odd frame that slipped through production that’s x’d out. The only way you’d see it is if you freeze-framed the cartoon.

Tex’s animators in this cartoon are Mike Lah, Walt Clinton and Grant Simmons.

Sunday, 23 April 2017

Generous Jack

Jack Benny was ridiculously cheap on the air. That was the idea. Ridiculous equals laughs.

The real Benny was generous, partly because he was boxed in by his radio/TV character. He felt the need to show people in real life he wasn’t cheap.

Some examples are given in this feature story in Modern Screen magazine of October 1942. Movie magazines aren’t exactly reliable sources of journalism but what’s contained in this article was echoed elsewhere for many years. Jack’s mind was elsewhere when he ran into people and his bedroom was laden with pills just in case he got ill. The only odd statement is at the end about giving a break to Rudy Vallee. Vallee was one of radio’s earliest stars and was giving breaks to others before Jack even started on the air.

The pictures below accompanied the article.

Benny’s from Heaven

But Jack’s no angel! He’s a Hellzapoppin’ zany with the biggest line of gags this side of Allen!

By KIRTLEY BASKETTE

One day, not long ago, Jack Benny met a slight acquaintance in the halls of NBC's Hollywood studios and stopped for a chat. The man mentioned the wife of a mutual friend who was very ill. "Zat so?" murmured Jack vaguely, puffing his cigar. "H-m-m-m-m — too bad." Then he changed the subject and strolled on with an absent-minded "So-long."

The acquaintance stared after him and shook his head. "That guy Benny!" he muttered angrily. "What a selfish dope! All he cares about is himself and his show. He must have a cake of dry-ice for a heart!"

A week or so later the same man ran into the ailing woman, now up and about and bustling along the Boulevard. He said she looked swell and what was the hurry? "Got a date to meet Jack Benny," she smiled. "I want to thank him for being so nice!"

"Benny!" sputtered the gent, recalling the disinterested episode. "Good Lord, why Benny?"

"It was the funniest thing," bubbled the lady. "I hardly knew Jack, you know. But one day when I was so sick, he showed up loaded with flowers and presents. He sat around all afternoon telling stories and making me laugh so hard I couldn't help get well. It was the day before his show, too. I know he was busy, and — well, I think he is swell."

Because he is modest, most people think Jack's stand-offish. Because he's shy, they call him cold. Because he plays tightwaddery for a radio gag, they'll tell you he's a penny pincher. Because he's gone absent-minded, wool-gathering on how to make folks laugh, they're sure Jack's distant, indifferent and selfish. Some call him stuck-up because he's been the number one chuckle champ for years; others paint him grass green with envy of Fred Allen, Bob Hope, Red Skelton or every other Joe Comic.

All of which is a lot of scuttlebut, as they say in the navy. If you don't believe me, you might ask Ann Sheridan.

Jack has just finished "George Washington Slept Here," with Oomphy Annie out at Warner Brothers'. Jack always makes buddies out of his movie leading ladies, and always before the picture is over they turn up on his radio show. Jack thought Ann would be particularly swell on a Sunday laugh spot, but when he suggested it, she shivered and shook.

"I'm allergic to radio mikes," protested Ann. "I'm likely to faint or draw a bamboozled blank and ruin your program. Sorry, Jack, but it's impossible."

Jack tried to soft-talk her out of it, but he saw Ann wasn't kidding. Mikes do convert her nifty knees to jelly and turn moths loose in her tummy. But Jack was convinced Ann would be terrific, and he had an idea. "Okay," he told her, "I'll write two complete shows — one with you and one without you — and rehearse 'em both. Then if you just can't go through with it at the last minute — well — you won't have to." And that's what he did — although it cost Jack a pretty penny and some horse-sized headaches, too, to double the order just to soothe Annie's nerves.

The first year that Jack's black Man Friday, Rochester, clicked on his program, he got a $10,000 check for Christmas. Every member of Jack's big staff, his writers, Bill Morrow and Ed Beloin, his entertainers, Phil Harris, Dennis Day, Don Wilson, and all the rest get regular raises on already fat salaries well above what their options call for. Nobody who has ever worked for Jack is happy with anyone else. His secretary, Harry Baldwin, has been with him 11 years. Two actors he brought out from Broadway several years ago haven't worked on Jack's show for months, yet every Saturday night their check is in the mail. On his army camp shows Jack personally foots all transportation and technical expenses, which run into four figures about every week. If I mentioned his private charities, I'd only embarrass a sensitive guy. But I can tell an incident on the "George Washington" set that happened just the other day.

passing the "buck" . . .

They were collecting for a certain war fund around the Warner lot, signing up the various stars for various amounts. It was all on the cuff and in advance, but when Jack was approached he said — "Oh, sure," and reached in his pants pocket, extracted a roll of century notes big enough to choke a cow and said, "I don't know how much is in it, but take it. Wait," he added, peeling off a lone dollar bill. "I need gas to get home."

Most of this abundant generosity in Benny comes from the fact that he has little use for the green stuff except to pass it around. He has been so up in the chips for so long that he knows it isn't mere bank notes that count.

You wouldn't think a hardened entertainer would be sensitive about his comic stock in trade. But the penurious, misery air Jack assumes for gags on the air waves touches him to the quick.

A Brown Derby waitress told me, '"Jack Benny doesn't over tip. He over-over-over tips." He's afraid somebody will think him a nickel-nurser. A couple of years ago when his wife, Mary, was in Honolulu, Jack cabled her one night. "Jack Benny cabling Mary Livingstone in Honolulu," said Jack. "Oh," replied the operator, "then you'll want the message sent on the deferred rate, won't you, Mr. Benny?" Deferred trans-ocean messages are lots cheaper, and in this case it made only an hour or so's difference, and the message wasn't rush at all. But Jack flushed — "No — no," he said hastily. "Send it straight — send it straight!" He was afraid even an operator would think him stingy.

Actually, the luxury requirements of Jackson Benny are pretty meager. He has never felt exactly comfortable in the plush life, remembering too well the hard times he waded through to success. He lives in a Beverly Hills colonial mansion of movie star proportions, all right, but that's mostly a gesture to Mary and his family. Jack himself holes out in his bedroom, which is his workroom, library, studio and about everything else. He has a complete radio transcription outfit there, recording machine and playback equipment. The walls are lined with bound scripts of his shows. He has dope and data scattered around on a couple of big desks and seals himself in amid dense cigar smoke for inspiration on this or that.

Like most Beverly Hills citizens the Bennys sport a fancy swimming pool in the back yard. Jack never uses it. Instead he goes down to State Beach, the public strand at Santa Monica, and mingles with the mob. He's a guy of the people, really, and is happiest when he's doing just the things they do. His biggest daily recreation is a walk downtown in Beverly to hang around the drug store. He used to get his biggest recreational kick driving his open roadster around town slowly, often with Joan, and buying her all the things she shouldn't have. He likes to go to the fights and movies and the Play Pier at Ocean Park.

slightly stupendous . . .

When the Jack Bennys first got settled in Beverly Hills, they used to entertain a lot, and like all Hollywood entertainers, they found that their parties soon became events. A guest list starting at ten zoomed to two hundred in no time. People they slightly knew came and kibitzed on the food and entertainment. One New Year's Jack and Mary threw a lavish party— with gay canopies all around the place, an orchestra, fancy catering and almost a stage set around the swimming pool. Everybody came — and stayed, and it was such a chilly night that the Hollywood night clubs actually beefed about Benny taking away their customers.

In the midst of the gala event, a good friend of Jack's came up to him and noticed that Jack wasn't having such a hell of a good time. He pointed to the mob. "It's colossal, Jack," he cracked. "Why don't you photograph it?" Since then the Benny's don't entertain like that. When they go in for good times it's with their close pals, and what they do are the little ordinary American fire-side diversions — cards, conversation and home movies, as a rule.

The intimate Benny set includes Barbara Stanwyck and Bob Taylor, Ronnie Reagan and Jane Wyman, the Ray Millands, the Mervyn LeRoys, Loretta Young and her husband, Tom Lewis, George Burns and Gracie Allen and Jack's in-laws, the Myrt Blums.

For a long time the clique maintained a Sunday night "Turnabout Club," the turnabout part being that each member took turns footing the check for an evening of dancing at Ciro's or some Hollywood glitter gallery. Jack loves to dance, and he's good, too, especially at a rousing rumba. Since the war and his army camp shows, his one night of stepping out has been stepped on. Sunday evening is Jack's high spot of the week in more ways than one. It's the only time he can relax — after the radio show is over — and as anyone will tell you, Jack's weekly radio stint is the essence of his life.

He worries about it from Tuesday until it goes on the air Sunday. Sunday night is the only night he lets down, when the "So-long, folks" signs him off the air waves. Monday he sleeps late and that is what his colleagues call "the wolves' day." Every Monday people who want Jack to attend to this or that, people with axes to grind, solicitors, business agents, tailors with fittings, salesmen and all extra-show business characters swoop down on Jack. He holds court far into the night. Tuesday morning he starts worrying again — about Sunday's show.

Jack is a great worrier — maybe that's why he's so good. His nails are chronically bitten down. He's a perfectionist, and he's always sure everything he does is terrible. The people who brand him disinterested and self-centered don't know that from Tuesday morning at 7:30 on (Jack is an early riser every day except Monday), Benny is deep in mental agonies about his next Sunday program. He puts in hectic work on it surrounded by his staff who tag after him to his several offices, scattered around Hollywood at NBC, his home, Paramount, Warner Brothers and Twentieth Century-Fox. During that time he is likely to stare old friends in the eye and not know them. Sometimes Mary Livingstone, after repeating the same thing to him five times and getting "H-m-m-m's" for answers, will cry, "Remember me? I'm your wife!"

benny's self-torture . . .

Jack himself bemoans this concentration because it takes plenty out of him, but he's convinced that his stuff depends on timing and finesse. That's one reason he feels so chagrined about his value as an army camp entertainer. He feels that the continuity type of program he puts out is not zippy and fast enough to make good watching entertainment for the doughboys. And while he doesn't beef about it, it's no secret that for him to stage a program where every faculty isn't just right is a torture his audience never knows about. When things aren't smooth as silk, Jack Benny dies a slow death.

Jack envies Bob Hope and Red Skelton and the only gag ad libbers who can toss off a show at the drop of a hat, tear themselves to pieces and love it. "If I was only about ten years younger like those guys" he wails. Jack always gives out with a 45-minute warm-up to compensate for the less slam-bang character of his program. And he's already made plans for a 13-week road tour of the camps this summer, devoted exclusively to entertaining soldiers with a show prepared especially for them. He'll pay the expenses, by the way, and it will cost plenty. But that's the only way Jack figures he can really do a good job and keep out of a coffin.

Health is a great concern of Jack's. Some people call him a hypochondriac. He's a great pill swallower, dieter and general health faddist. "Benny," Phil Harris once cracked, "eats an 11 course meal — five courses of food and six courses of pills!" The other day a waitress at Warner Brothers brought Jack his lunch; it was Jack's tomato day. As she set the plate down the waitress gasped, "Oh, Mr. Benny, I'm so sorry!"

"What's the matter?" gulped Jack.

"Why, your tomatoes — they're sliced, and I forgot you like them quartered!"

Jack doesn't drink. When he does he falls asleep. If he goes for a cocktail before dinner it's always a pink lady. He's always furrowing his brow about the cigars he devours but can't stop them. His dietary weakness is rich food and late night stuffing. "Restaurants will be the death of me," he wails after stocking up on a choice morsel.

Oddly enough, Jack's not one bit touchy about the signs of Old Man Time. In fact, he's always joking about his thinning, gray hair. A few days ago on the "George Washington" set he had a scene in which he was drenched in a rainstorm. After the prop storm deluged him a few times, Jack cracked, "For gosh sakes — get me out of here — my hair's slipping."

don't tell allen, but . . .

Probably the highest glee of Jack's week is listening to the caustic comments of Fred Allen which rip his own show to pieces every Sunday. He carries a couple of portable radios with him to be sure not to miss them, smoking a stogie furiously and chuckling when Fred — who pulls no punches — hits a particularly tender spot. The Allen-Benny feud, by the way, is entirely impromptu. It was never a studied gag, like the Walter Winchell-Ben Bernie battles. Jack and Fred, who have known each other from vaudeville days, never correspond or arrange pots at each other. Each Sunday it's a complete surprise to Jack, and he's never yet got really mad.

Jack is always telling his friends that he'd give anything, including a small fortune, for a year's rest. Sometimes he probably means it. "I'm tired," he sighs. "The pace is killing me," but there's always some reason why he can't stop. Right now, of course, the reason is that Jack thinks he'd be unpatriotic to loaf when the government can use the cartwheels he collects each week and when the public can use a few belly laughs.

What Jack Benny will probably do if he ever ends up on the retired list is to sit and reminisce — his favorite recreation today — about the fun he's had making other people laugh. About the kick of giving breaks to radio stars like Rochester, Kenny Baker, Rudy Vallee, Phil Harris, Dennis Day and a dozen more. And the headaches he's enjoyed stewing on picture sets, taking it on the chin from sassy birds like Fred Allen and generally worrying himself sick — and happy. Probably Jack Benny will be most remembered in Hollywood's archives by his last picture, "To Be or Not To Be" — because it undoubtedly is his best to date. It would be a funny thing if some future Hollywood historian links him with the one he's doing now — "The Meanest Man in Town."

Because, take it from me, that's one thing Jack Benny is not and never has been — and the people who get that impression just don't know their Benny.

The real Benny was generous, partly because he was boxed in by his radio/TV character. He felt the need to show people in real life he wasn’t cheap.

Some examples are given in this feature story in Modern Screen magazine of October 1942. Movie magazines aren’t exactly reliable sources of journalism but what’s contained in this article was echoed elsewhere for many years. Jack’s mind was elsewhere when he ran into people and his bedroom was laden with pills just in case he got ill. The only odd statement is at the end about giving a break to Rudy Vallee. Vallee was one of radio’s earliest stars and was giving breaks to others before Jack even started on the air.

The pictures below accompanied the article.

Benny’s from Heaven

But Jack’s no angel! He’s a Hellzapoppin’ zany with the biggest line of gags this side of Allen!

By KIRTLEY BASKETTE

One day, not long ago, Jack Benny met a slight acquaintance in the halls of NBC's Hollywood studios and stopped for a chat. The man mentioned the wife of a mutual friend who was very ill. "Zat so?" murmured Jack vaguely, puffing his cigar. "H-m-m-m-m — too bad." Then he changed the subject and strolled on with an absent-minded "So-long."

The acquaintance stared after him and shook his head. "That guy Benny!" he muttered angrily. "What a selfish dope! All he cares about is himself and his show. He must have a cake of dry-ice for a heart!"

A week or so later the same man ran into the ailing woman, now up and about and bustling along the Boulevard. He said she looked swell and what was the hurry? "Got a date to meet Jack Benny," she smiled. "I want to thank him for being so nice!"

"Benny!" sputtered the gent, recalling the disinterested episode. "Good Lord, why Benny?"

"It was the funniest thing," bubbled the lady. "I hardly knew Jack, you know. But one day when I was so sick, he showed up loaded with flowers and presents. He sat around all afternoon telling stories and making me laugh so hard I couldn't help get well. It was the day before his show, too. I know he was busy, and — well, I think he is swell."

Because he is modest, most people think Jack's stand-offish. Because he's shy, they call him cold. Because he plays tightwaddery for a radio gag, they'll tell you he's a penny pincher. Because he's gone absent-minded, wool-gathering on how to make folks laugh, they're sure Jack's distant, indifferent and selfish. Some call him stuck-up because he's been the number one chuckle champ for years; others paint him grass green with envy of Fred Allen, Bob Hope, Red Skelton or every other Joe Comic.

All of which is a lot of scuttlebut, as they say in the navy. If you don't believe me, you might ask Ann Sheridan.

Jack has just finished "George Washington Slept Here," with Oomphy Annie out at Warner Brothers'. Jack always makes buddies out of his movie leading ladies, and always before the picture is over they turn up on his radio show. Jack thought Ann would be particularly swell on a Sunday laugh spot, but when he suggested it, she shivered and shook.