100 years ago, if you mentioned the name “George Stallings,” the manager of the National League Boston “Miracle” Braves would come to mind. Today, diehard baseball history buffs should recognise the name. But keen-eyed fans of animation today might remember the name from title cards of Van Beuren cartoons of the early 1930s.

100 years ago, if you mentioned the name “George Stallings,” the manager of the National League Boston “Miracle” Braves would come to mind. Today, diehard baseball history buffs should recognise the name. But keen-eyed fans of animation today might remember the name from title cards of Van Beuren cartoons of the early 1930s.

Cartoondom’s George Stallings was the son of the baseball field boss, and arguably can be considered one of the major figures in early New York animation. Donald Crafton’s book “Before Mickey” relates how Stallings was hired by the Bray studio about 1916 and eventually became manager of it until 1924 when he was replaced by Walter Lantz; Crafton says Stallings got sick, while Michael Barrier’s “Hollywood Cartoons” states Bray got tired of Stallings coming in late and fired him.

Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic” relates how Stallings popularised the rotating disc on animation drawing boards.

Stallings Sr. retired to a home in Haddock, Georgia, and died there in 1929. The year before, the Macon Telegraph profiled his son in a feature story published on February 12. It outlines how he got into the animation business and the studios where he found employment in New York. You can also get an idea of the horrendous working conditions. No wonder the studios were able to turn out one cartoon a week.

How George Stallings’ Son Makes Comic Cartoons Move

Hundreds of Drawings Back Each Jump of Felix the Cat

A Peep Into the Studio of Vernon Stallings Reveals the Intricate Methods of Making Apparently Simple “Moving Picture Cartoons;” Studio Near Here

By WILLIE SNOW ETHRIDGE

THERE is a man spending the winter near Macon who has made millions of funny motions for your special amusement. It is a sure thing you have seen them if you have been to the movies anytime in the last ten years, for these funny motions go wigging and wagging and jumping and jerking across the screens daily.

The man Is Vernon Stallings and the funny motions are those in the pictures of Felix the Cat, of Tad’s Daffodils, of the queer little creatures in Aesop’s Fables and of all the other jumpy figures in the animated picture strips. Mr. Stallings has drawn pictures for every animated movie strip that has ever been shown in moving pictures. And that means millions and millions of pictures— and then some.

While watching one of those inimated [sic] strips did you ever begin wondering how those absurd little figures could be made to dash up and down rope ladders, swing houses about on their tails, drag pirates across the decks of ships and heave them into the ocen [sic] and do all the other fool things that they do in their brief moments on the silver screen?

If you have been wondering about it, you may now let your mind rest in peace, for I made a 30-mile trip into the country recently to find out this very thing from Mr. Stallings, who makes those odd creatures act that way. Mr. Stallings is visiting his father, George Stallings, who is known, even to the members of the femine sex, as the “miracle man of baseball.” George Stallings, as you perhaps know, has a country home five miles or more, and I believe more on the other side of Haddock. It is here that his son has been spending the winter months resting up from the grind of New York life.

Just as soon as I was face to face, or to be exact, face to chest, for he extends six feet five inches into the air, with Vernon Stalling, I jumped into this subject of how he made those comic figures so muchly animated. “It takes from three to five thousand drawings to make each one of those little strips which are shown in five or ten minutes on the screen,” he answered promptly.

“But that doesn't explain how it is done,” I argued.

“No,” he said with a smile and a very slight shrug of his broad shoulders. “It is not ae simple as that. Come on over to the shack where I do my drawings and I will explain It fully.”

So we left the house of George Stallings and crossed the yard to a little building which Vernon Stallings has dubbed the “Penny Arcade.” It is here that he had set up his studio for the months of his visit. The desk and tables were piled high with drawings and the chairs were filled with papers.

He pulled up two chairs to his drawing board and with great patience began explaining the process of making an animated movie. The drawing board had a rectangle in the center into which fitted a piece of window glass. Flush with the board and the glass, was a steel bar In which were fixed two cylinder pins about one half-inch in length. Beneath the window glass was an ordinary electric bulb.

Mr. Stallings placed a clean sheet of white paper which had holes punched in the top to fit on the cylinder pins upon the glass and with his pencil poised in his fingers announced: "Now we are ready to start on our strip. Let's Imagine we want to make a picture of a man tipping his hat to Leatrice Joy.”

Mr. Stallings’ pencil began to fly over the paper. With a stroke here and a stroke there, he was drawing a little man in the act of tipping his hat.

How It Is Done

“We draw the man,” he explained, as his pencil dashed about, “in the first position of tipping his hat. Then we place another sheet of paper right on top of drawing one. You see, the light under the board is showing the image of the first drawing even through the blank sheet on top of it, so we can now draw the next position of the man without disturbing the frst. This position is the final which his arms will move into, holding the hat in his hand.

However, the arm is the only part of the body in action, so that is all that is necessary to draw.”

Having finished drawing the arm, holding the hat, Mr. Stalling began flipping it up to see the drawing underneath.

“Now you will notice as I flip this paper that there is quite a gap from the first position of the man tipping his hat and the one I've just drawn with the hat in his hand,” Mr. Stallings continued, looking at me expectantly.

I gazed at the two drawings as hard as I could, but the hat seemed to be tipped all right to me. Nevertheless, I said “yes sir.”

I gazed at the two drawings as hard as I could, but the hat seemed to be tipped all right to me. Nevertheless, I said “yes sir.”"These two positions are not considered enough to make this action smooth with the proper timing of a man tipping his hat," he continued. "Still we have the extreme positions so we merely make two more drawings equi-distant in between, and now we have four drawings forming the entire movement. We number these drawings according to their sequence, the ne we drew second being numbered four, as that is the final position in the movement. You see?” I nodded my head.

“Well, now, unless Leatrice Joy freezes the man solidly he will put the hat on his head,” he continued. “New drawings are not necessary for this. Just reverse the old ones and the man replaces his hat. Now you are back to drawing No. 1.”

I gave a sigh of relief to be rid of the little man—and, yet, I wasn’t doing anything but looking on. Mr. Stallings was doing all the work.

“That would be merely the beginning of a strip,” he said with a smile. Then lifting up a stack of drawings about a foot deep from his desk, he mentioned that they were some he had just completed for Bill Nolan, who issues the Illustrated News Laughs. The plan of the Illustrated News Laughs is to take some item from the day’s news and make it into an animated series strip.

The News Laugh, on which Mr. Stalling had been worked, was the announcement of some noted educator that children are more ingenious than grown ups. Mr. Stallings had made 175 separate drawings showing a child in the act of picking up two bones for drum sticks. And that was just a small part of the strip. He had already made 1,500 drawings on the news laugh alone, and yet, it was far from being completed.

Making the drawings would seem to be enough of a job, but the animator has to think up the funny stunts for the figures to execute—and the more funny stunts, the better the strip, of course.

“If we say that, we take a lot of pains to be funny, that is just it,” Mr. Stallings declared, “The pains seem to get the laughs. If we stick a pin in a baby, it's funny. If horse kicks him in the face.it is funnier. So we are painfully humorous. The motion picture cartoon has first claim pn the First Aid Kit,for in these cartoons it is the license of the producer to distort and disfigure as well as parting the baby's hair with an ax. The kid can not only nibble on the bottle, but he can chew it up and swallow it. Then if he wails to, he can blow gazing crystals, tumblers, windshields or what have you. So our audience sits back and giggles at these nonsensical bits and says, ‘Oh, gosh, he really doesn't do that. He's only a drawing.’ But to us who draw him, he lives and we try to make him just as human as anybody else, except saxophone players."

“How do you know when you have made enough funny movements for a motion picture cartoon?” I asked Mr Stallings when had finished laughing at the humorous manner of his speech.

“Well, that takes some more explaining,” he said, and I screwed up my eyes again as tight ae possible, and began concentrating as hard as I knew how.

"When we have completed our drawings,” he continued, “they are placed and photographed one after the other under a camera. They are consequently recorded in sequence on the long roll of film within the camera. However, there is a tempa or timing on this action which makes them pause properly, and do things in a natural way. This timing is arrived at by natural arithmetic. There are 16 pictures to one foot of motion picture film, and when these pictures are run off on the screen, they move at the average rate of 16 pictures a second.

“If we want to hold a certain pose for a second, whe [we] photograph that single picture 16 times. If for half the length of time, it to photographed eight times and so on. If a figure walls [sic] into a scene very slowly, then each position of the walk is given three exposures. Normally it is given two exposures, and if the action as rapid as with pinning, it is given one exposure for each drawing. Exposure sheets are usually written with each scene. Opposite the number of the drawing is the number of exposures with which that drawing is to be photographed. This is very simple to follow under the camera, and if the total number of exposures are added and divided then we know exactly how many feet of film are required to photograph that scene. The usual length of a cartoon is between 500 and 600 feet.”

Mr. Stallings got up from his drawing board and showed me some film and focused a camera to make the explanation clearer to me, but I had already taken in all I could, so I didn’t understand even what he was making more clear. “What I really want to know is how you got into this intricate business?” I asked when the explanation had been completed and he had settled himself ones again before his drawing board.

First Hardships

“All my life I wanted to draw,” he said with a smile, as he turned a drawing pencil between his long fingers. "When I was a buy I spent hours drawing. And then when I went to the University of Georgia, I was so much more interested in drawing than I was in my studies. I left there after the first year. I went to New York and studied cartooning.

"In 1911 I came back to Georgia and got a job on The Atlanta Journal in the art department. After about a year on The Journal, I went to New York and began doing sport cartoons for the Adams Newspaper syndicate. All the time I was drawing these sport cartoons, I was experimenting on the animated movies, which had just begun. The first animated movie was Winsie McKay's [sic] Gertie. All the money I made from my newspaper work I spent on the movie cartoons. You know how that is.

“About this time,” Mr. Stallings continued, “I met a man both rich and influential—sounds like a story doesn’t it?—who arranged for me to do movie cartoons with the Gaumont movie people. Just as I thought I was all fixed, it was discovered that a man named Bray ad had the animated movie patented and no one else could make them. The only thing left for me to do was go to work for Bray. He was drawing the Heeza Liar series and I worked with him.”

“About this time,” Mr. Stallings continued, “I met a man both rich and influential—sounds like a story doesn’t it?—who arranged for me to do movie cartoons with the Gaumont movie people. Just as I thought I was all fixed, it was discovered that a man named Bray ad had the animated movie patented and no one else could make them. The only thing left for me to do was go to work for Bray. He was drawing the Heeza Liar series and I worked with him.”Later the cartoonists discovered there was a way to get around Mr. Bray’s patent and various producers began to make the animated strips, according to Mr. Stallings. So Mr. Stallings left Bray and went to Barrie [Barre] at Fordham to make the animated strips of Mutt and Jeff.

“When you say, Mr. Stallings, that you drew animated cartoons of Mutt and Jeff do you mean that you put the action into the strips Bud Fisher had already drawn for the newspapers?” I asked.

“Oh, no, no,” Mr. Stallings exclaimed. “Barrie bought from Fisher only the rights to his characters. He paid Fisher $1000 a week in royalties for the use of the two characters alone. It was up to the animators with Barrie to make up the scenario for the characters. All the stunts that you have seen Mutt and Jeff do on the screen are the brain children of the animators.

“The making of an animated strip is not a one man job,” Mr. Stallings continued, “but like a one man top [sic] it takes a lot of people a long time to put up what one man thought of. The average studio, turning out a picture every week requires a staff of from 30 to 55 people. They are known as animators, the men who pencil the actual movements and are responsible for the acting and the comedy; the inkers, those who ink in the penciled drawings of the animators; the tracers, those who complete the drawings, put in the blacks and tones and check up on all mistakes; and the camera man who is the automaton who give each drawing the number of exposure each drawing calls for.”

At one time, Mr. Stallings was in entire charge of all the International animated cartoons. They included Jerry on the Job, Silk Hat Harry, Tad's Daffodills, the Katzen Jammer Kids, The Hearst cartoons, for the International cartoons were owned by Hearst, were very popular for about six years, according to Mr. Stallings. Then Hearst divided the International Productions into the Cosmopolitan Productions, which included only feature pictures, and into the International News Reel. Mr. Hearst abandoned entirely the production of short comic strips.

A New Idea

Mr. Stallings was associated with Paul Terry in the production of the Aesop's Fables for a year and a half. The Aesop's Fables had a tremendous, circulation according to the cartoonist. They cost Terry about $2,000 a week to make, and they brought in around $22,000 a week.

"The short strips have always been the step child of the movie game,” Mr. Stallings said. “They have always been considered fillers, and yet, they were so in demand at one time that we worked all day and night frequently. Our field is not overflowing with good men and at the heighth of the cartoons' rage we had no hours at all. A man just worked until he was carried out on a shutter. I have seen the whole staff, girls and all, work from 9 o'clock one morning until 9 o'clock the next. Through the wee hours of the morning we would send out for coffee. The container was usually a thousand foot film can and the odor of gun cotton made the coffee taste like paregoric. But we would drink marbles in those days. We would drink half the can, saving the balance. An hour or so later some one would be struck dumb with a doughnut in his wind pipe and hasten to heat the coffee. This was done by placing the tip end of an electric light bulb In the coffee so the liquid did not come in contact with the socket attachment. If there was anything else we couldn't or didn't do we never found it.”

Mr. Stallings is somewhat at a loss to understand why they have dropped off in popularity to such an extent.

"People tell us they like the cartoons and reports on them prove them to be popular, but It Is a job to sell them,” he said a bit ruefully. "We don't know and will probably still be cutting paper dolls when we find out. However, so many of the picture houses are “de luxing” their programs with vaudeville and have discarded short subjects in favor of this new attraction.”

Mr. Stalling was with the Out of the Inkwell Producing company before he came South this fall. They are the people who do the clown cartoons. And now, though Mr. Stallings stays busy from early morning until night drawing cartoons — he has made 700 small drawings in one day — he is working in his spare moments on a new idea.

And this new idea, which is a dark secret now, will cause quite a sensation if it works out as it should. When it is fully worked out, Mr. Stallings will leave the “Penny Arcade'' and return to his family, which consists of a wife and two children, in Now Rochelle. And if his big idea takes as many drawings to explain it as one of these strips he has been making, he will surely travel heavily laden.

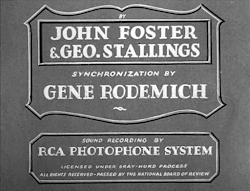

What Stallings’ invention was, we may never know; he doesn’t seem to have patented anything. With the coming of sound, cartoons became popular for theatre-goers, and Stallings’ career briefly ascended at Van Beuren. He was part of the team that created the human Tom and Jerry in 1931 (borrowing an awful lot from the Don and Waffles cartoons made a little earlier), directed the two efforts starring Amos ‘n’ Andy, and then became head director. The last cartoon where he receives screen credit is on Fiddlin' Fun, starring Cubby Bear. There’s a noticeable improvement compared with the Van Beuren cartoons made a few years earlier. Cubby’s design is appealing and consistent throughout. Stallings has chosen various angles of action. And there are decent stretches of animation, perhaps thanks to the presence of Carlo Vinci on the staff.

What Stallings’ invention was, we may never know; he doesn’t seem to have patented anything. With the coming of sound, cartoons became popular for theatre-goers, and Stallings’ career briefly ascended at Van Beuren. He was part of the team that created the human Tom and Jerry in 1931 (borrowing an awful lot from the Don and Waffles cartoons made a little earlier), directed the two efforts starring Amos ‘n’ Andy, and then became head director. The last cartoon where he receives screen credit is on Fiddlin' Fun, starring Cubby Bear. There’s a noticeable improvement compared with the Van Beuren cartoons made a few years earlier. Cubby’s design is appealing and consistent throughout. Stallings has chosen various angles of action. And there are decent stretches of animation, perhaps thanks to the presence of Carlo Vinci on the staff.

Then Stallings found himself on the outs. In 1934, Amadee Van Beuren hired Burt Gillett, the director of Walt Disney’s Three Little Pigs, to take over the studio and the Gillett broom swept clean. Ironically, Stallings found himself at Disney in 1935 (according to his obit in the Valley Times) working on stories and even being given some kind of supervisory position on Merbabies, which was made by Harman-Ising Productions for Uncle Walt. The 1950 census lists him living in Burbank, divorced, and working 60 hours a week as an “artist-writer, motion picture cartoon,” though the studio is not reported. His obit stated he was the author of the Uncle Remus comic strip for 18 years—Stallings grew up with Joel Chandler Harris’ children—and created the Soapy Smith strip.

He was born in San Jose, California on Sept. 9, 1891 and died of cancer at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills on April 9, 1963.

No comments:

Post a Comment